The Approaches to Petrograd.

A Soviet account of this raid (in which the times differ

from those in the British version) has its own interest:

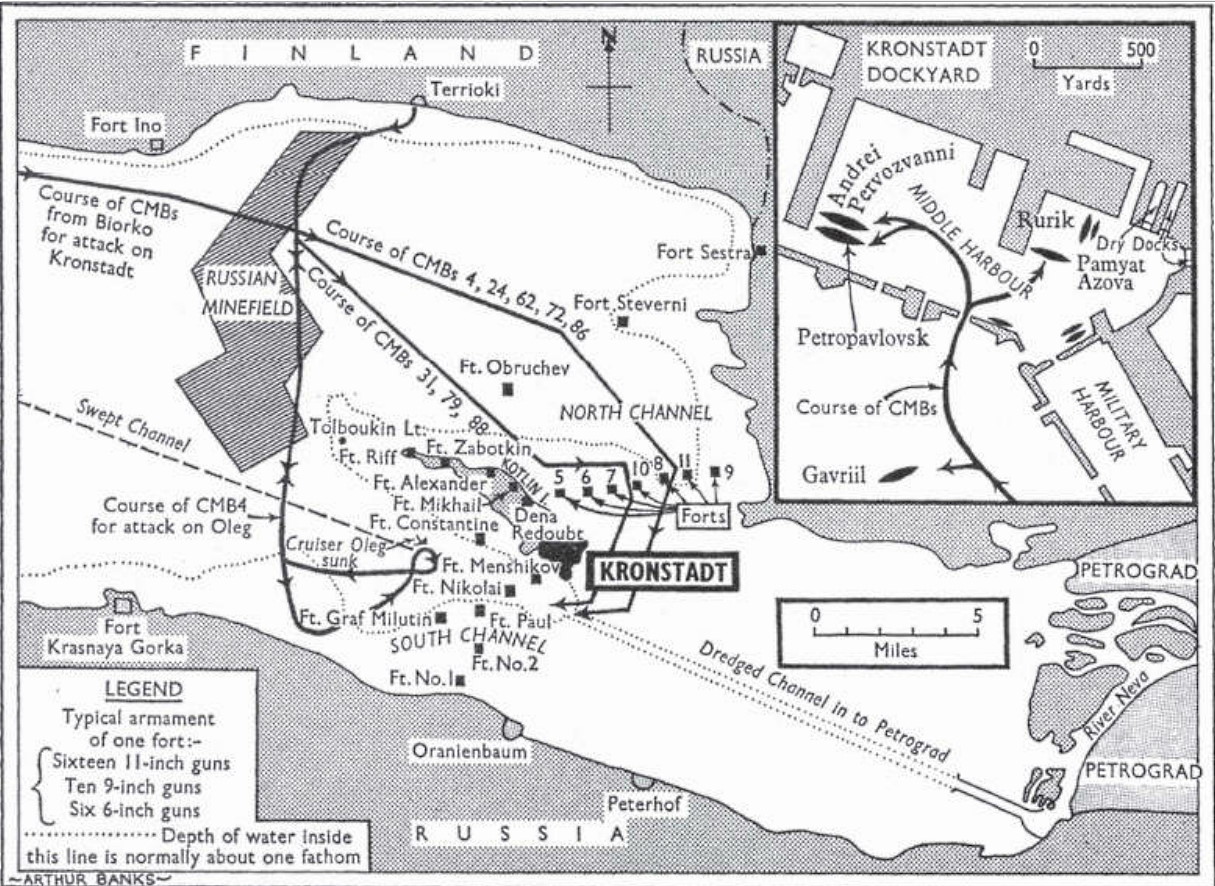

On 18th August at about 0100, five British C.M.B.s left

Biorko, and a little later two similar craft left Terrioki. They all made a

rendezvous in the vicinity of Fort Ino, and proceeded in company by the North

Channel to the rear of Kronstadt. At 0400 they were sighted in the proximity of

Fort Obruchev. After this, the craft proceeded between Forts Nos. 3 and 4, and

passed Kronstadt. At 0345 aircraft appeared over Kronstadt and “strafed” the

ships and harbour basins with tracer bullets and dropped bombs. At 0420 the

destroyer guardship, Gavriil, anchored in the roadstead, which was returning

the fire of aircraft attacking her, sighted two boats and simultaneously heard

a large explosion in the harbour close to the workshops of the Baltic Yard. The

Gavriil opened fire and with her first shot sank one boat, while the other

disappeared behind a defence-work. The explosion in the harbour was caused by a

torpedo which had missed the Gavriil and had struck the basin wall.

The Gavriil also sighted two or three boats entering the

harbour at very high speed and firing their machine-guns at the ships berthed

there. She could not fire at these boats for fear of damaging our own vessels.

They torpedoed the Pamyat Azova and almost simultaneously, at 0425, the Andrei

Pervozvanni was blown up, after which the C.M.B.s nipped out of the harbour

towards the south. During their exit two boats were sunk by gunfire from the

Gavriil, which quickly sent a boat to save 3 officers and 6 ratings. The

C.M.B.s which had sunk the Pamyat Azova and Andrei Pervozvanni continued to

fire with their machine-guns.

As already mentioned, the C.M.B.s got through the North

Channel, where four were sighted by Fort Obruchev, moving at very high speed.

As the fort was then returning the fire of attacking aircraft it could not open

fire on the C.M.B.s, though they sprayed it with machine-gun fire. The fort

immediately telegraphed to the Fortress Staff who in turn informed the Staff of

the Active Squadron Command. But the latter could not do anything on this

belated information because its reception coincided with the Gavriil opening

fire. The passage of the C.M.B.s was also seen by Forts Nos. 3 and 4 but they

could not do anything because the first had no guns whilst the other was

replacing her weapons and was restricted to rifle fire. Allowing for the 40

knot speed of these boats, it is clear that everything happened with

unaccustomed rapidity, in darkness and during an air raid. Moreover the very

idea of an attack by C.M.B.s was completely unexpected both in its conception

and the boldness of its execution. Not until after the boats had broken through

did the forts switch on their searchlights and go to action stations, and by

that time the C.M.B.s were to the rear, where most of the guns were unable to

train.

On their way back the C.M.B.s, moving in two groups at full

speed, again by the North Channel, were picked up in the beams of the searchlights,

and came under heavy machine-gun fire from the forts. They also came under

gunfire, but this was unsuccessful. Thus out of eight attacking C.M.B.s, three

were sunk by the Gavriil’s fire and five got away. From the moment when the

C.M.B.s left the harbour the air attacks, which had been delivered almost at

masthead height, ceased. The din of their engines and their machine-gun fire

were of great assistance to the C.M.B.s, for the A.A. weapons were fully

occupied with aerial targets, and superfluous personnel were sent below decks

or under shelter.

The torpedo which struck the Andrei Pervozvanni displaced

four armour plates on the port side, two of them being torn away some two feet

from the side. The compartments between Nos. 4 and 13 frames up to the second

armoured deck were flooded, and between Nos. 13 and 15 frames to the

orlop-deck, one man being killed and two injured.

The Commission of Enquiry reached the following conclusions

on the reasons for the success of the attack:

(a) The complete unexpectedness of the idea of a C.M.B.

attack on Kronstadt.

(b) The complete confidence in the impossibility of any sort

of naval operation by way of the North Channel.

(c) The complete distraction of the attention of the forts,

batteries, signal station and ships, by aircraft.

(d) The shallow draught of the boats which allowed them to

proceed on the surface at 40 knots.

So much for the Soviet point of view. From the British there

was no doubt about the result; at the cost of three C.M.B.s, Operation “R.K.”

had achieved Cowan’s purpose. Of Zelenoy’s active fleet only a handful of

destroyers and submarines remained. There was no longer any major threat to the

British Baltic Force, or to the seaward flank of Laidoner’s and Yudenitch’s

armies—unless the Bolsheviks managed to commission some of the heavy ships

which lay idle in the shipyards of the Neva. “Deeds of this kind have in times

past built up the fame of the English Navy, and this feat has once more shown

the world that when England strikes it strikes hard,”

wrote Mannerheim who fully appreciated the implications of

Cowan’s success for his own country’s future. The Estonian Foreign Minister was

“especially jubilant over this success.” Madden said: “This successful

enterprise will rank among the most daring and skilfully executed of naval

operations. On no other occasion has so small a force inflicted so much damage

on the enemy. Rear-Admiral Sir Walter Cowan deserves generous recognition for

the able foresight, planning and preparations which led to this great naval

success.” But not all those who carried out this enterprise returned to “enjoy

the fruits of their labours.” Six officers had been killed, including Brade and

Dayrell-Reed, and nine ratings, whilst Bremner and Napier were among the three

officers and six ratings rescued by the Gavriil’s boats who had to endure

Bolshevik prisons (though they were not seriously ill-treated) before they were

released. Cowan, in his speech to the survivors, said: “The losses are heavy,

but there is not one single incident to regret or one which could have been

avoided. The three boats which were lost went most gloriously, fighting

indomitably to the finish. I venture to think that their end will have as great

an effect in keeping the remainder of the Bolshevik Navy quiet as will the

devastation you have wrought in their harbour—the strongest naval fortress in

the world, ravished and blasted by under fifteen splendidly disciplined and

dauntless Britons.” “They all deserve the V.C.,” wrote the Cleopatra’s

navigator. Two were awarded, to Dobson and Steele; Agar and three other

officers received the D.S.O., eight officers the D.S.C., whilst all the ratings

were decorated with the C.G.M. in recognition of their valour in striking a

blow which, in one brief hour, achieved Cowan’s aim, destruction of the enemy

battle fleet. “After this nothing bigger than a destroyer moved again.”

Almost everyone was pleased—except the British Cabinet.

Wemyss wrote:

I have been awaiting further news of your brilliant

action before writing, but can wait no longer to congratulate you and all

concerned. It appears to have been an extraordinarily gallant and successful

attack, and I am in hopes that you may get some permanent relief from the

strain of the Baltic. I have, as you can imagine, been thinking about you and

yours constantly, and I think I can realise the difficulties of your situation.

You probably also realise how almost impossible it is to get real help or

guidance from our so-called Cabinet with their slipshod methods and want of

definite policy which inevitably leads to difficulties. The permission for you

to attack was obtained, so to speak, on a snap vote and I took the opportunity.

But they don’t or won’t understand the situation.

The Admiral who went to announce the success of the attack

to the Cabinet met, greatly to his surprise, with a far from cordial reception.

The sinking of the Baltic Fleet was the last thing they desired when, though

openly disavowing the Bolsheviks, they were secretly negotiating for the

withdrawal of British forces from Archangel. Wemyss was so disgusted by this

example of political opportunism that he tendered his resignation. But he had

either done this, or threatened it, too often in the past six months, to be

taken seriously.

This removal of a major impediment to a military advance

towards Petrograd and to the operations by Cowan’s force did not, however,

allow the British force to relax. Ships and submarines continued their patrols

and minelaying against sorties by Bolshevik destroyers, minelayers and submarines

which the Admiral warned his captains were likely to be intensified in

retaliation for the Kronstadt raid, in addition to bombarding the seaward flank

of the Red Army in support of the Estonians. Their work was, to quote Cowan,

“tireless, dauntless and never-ending and with never the relaxation of lying in

a defended port with fires out and on full rations; in cramped navigational

waters necessitating the almost constant presence on deck of the captain, and

always within range, and often under fire of the guns of Krasnaya Gorka.”

Donald’s planes likewise carried on their frequent raids against Kronstadt,

where their principal target was the docked Andrei Pervozvanni. In all they

made some sixty raids on the Bolshevik base. On 3rd September, 1919, one of

their bombs exploded only thirty yards from the docked battleship. Next day a

bomb splinter wounded a man on board a minesweeper. On the 14th, two bombs

damaged an auxiliary vessel; on 8th October, one struck another ship; and six

days later the destroyer Svoboda and submarine Tigr were strafed whilst out

exercising, when the former vessel suffered slight damage and casualties. “From

these results it may be concluded that the damage caused by enemy air raids was

generally insignificant,” was a Soviet historian’s conclusion. It is not,

however, a reflection on Donald’s men, for the same writer gives the reason:

“the bombs used by the British were quite inadequate for their purpose.” Moreover, he implies that their other

activities were of considerable value when he refers to the efforts made by

Bolshevik planes, albeit unsuccessful, to locate and attack Donald’s airfields.

But, as Cowan pointed out to the Admiralty on 20th August, none of his ships

carried guns of sufficient calibre to deal with the major obstacle to an

advance by Laidoner’s and Yudenitch’s armies, Fort Krasnaya Gorka, for which

reason he asked that he might be provided with two long-range monitors. He had,

however, to add that the Estonian Army would not advance so long as the Allies

refused to recognise their country’s independence; indeed, that in the absence

of this the Estonian Government was seeking to arrange an armistice with the

Bolsheviks. The Admiral also said that the Russian North-West Army, though it

had recently been reinforced by six British tanks, was unlikely to make their

much vaunted advance in view of “their disobedience and disregard of General

Gough’s suggestions, their perpetual quarrelling amongst each other, and

intrigue amongst themselves and with the Germans.” The Admiralty’s reply to

Cowan’s request for monitors was to the effect that, since all experience

showed that fortresses could not be reduced by naval bombardment alone—the

Dardanelles were foremost in their minds—such vessels would not be sent to the

Baltic until Laidoner’s or Yudenitch’s armies might begin a serious advance on

Petrograd—if, indeed, they should do so before the winter called a halt to

naval operations in the Gulf.

Towards the end of August Agar’s two small C.M.B.s made

their final venturesome trips into Petrograd Bay. Fully aware that they could

not hope to continue them much longer before the Bolsheviks learned of their

activities and took countermeasures, their purpose was to bring out S.T.25—Paul

Dukes—whom the Government had ordered to leave Russia before he tempted fate

too far. They also wanted this singularly brave man’s first-hand report on

conditions in Petrograd in order to contest the growing opposition of the

Labour leaders who viewed the Reds through spectacles as opaque as they were

rosy. Agar was all but successful on the 23rd, Dukes and a friendly Russian

midshipman being in sight of C.M.B.7 when their skiff sprang a serious leak and

they were obliged to swim for the shore. Dukes then decided against risking

this route again and that he would leave Russia by another: he managed it

across the Latvian front, reaching Helsingfors on 7th September. Before this,

however, Agar, unaware of Dukes’s changed plans, made a further attempt to

bring him off by sea on 26th August. This time C.M.B.7 was detected by the

forts in the North Channel which opened fire. A shot carried away the boat’s

tiller ropes so that, out of control, she ran on to the breakwater joining Fort

No. 5 to Kotlin Island. By superhuman efforts Agar and his crew managed to get

the boat off and plug the holes in her bottom. Then, using an improvised sail,

and baling hard all the way, they somehow managed, notwithstanding daylight, to

complete the hazardous return voyage to Terrioki in just under twelve hours.

This achievement is as remarkable as the Bolshevik’s failure to impede it. “Was

their escape a miracle,” wrote Agar, “or an answer to prayer? I am sure it was

both.”

Having destroyed C.M.B.7, Agar closed his Terrioki base and

went to Biorko to collect the repaired C.M.B.4. In her he led two of the larger

C.M.B.s by night into the swept channel leading to Kronstadt to lay four small

submarine mines. This operation was, however, seen by the Bolsheviks who sent

out minesweepers, escorted by the Svoboda, to clear them on 4th September.

After this Agar and his small band who, almost unique for naval officers and

men, had been directly employed by the British Secret Service, returned to

England.

At the end of August Zelenoy achieved some small revenge for

the Kronstadt raid. On the 31st, after six weeks of inactivity, the Pantera

left Kronstadt and,

having passed Tolboukin Light, submerged to periscope

depth. At 1430 a four-funnelled destroyer was sighted to the S.W., but she

quickly disappeared. Investigating the area, now moving deep, now watching

through her periscope, the submarine next saw two destroyers anchored to the

east of Seskar Island and decided to attack them. (These were the Abdiel and

Vittoria, Lieutenant-Commander Hammersley Heenan, which were on patrol. Cowan’s

instructions allowed them to anchor during reduced visibility by night and

Curtis had decided to take advantage of this in order to give his officers and

men some relief from the strain of war watchkeeping.) The Pantera steered to

get closer to the shore and attack from the north-west, because the destroyers

were anchored in relatively shallow water: after the attack it would be

essential to escape quickly into deeper water: it was also preferable to make

the approach from up-sun. At 2110 the Pantera went in to attack the destroyer

anchored further to seaward and at 2119 fired two torpedoes from her forward

tubes. She then dived to 80 feet and touched bottom. Half a minute after firing

a big explosion was heard, but the submarine was below periscope depth so that

the result was not observed. (The Pantera’s torpedoes struck the Vittoria which

sank in five minutes; fortunately the Abdiel was able to rescue all but eight

of her crew.) Shortly after this several shots were heard, evidently fired by

the second destroyer. On surfacing a little later, however, it was too dark for

the Pantera to see anything. So, having again dived to 40 ft., she set course

for Kronstadt. Not until 1120 the following day, when Tolboukin Light was

abeam, did the Pantera surface. By this time the pressure within the submarine

was so great that the measuring instrument’s needle was off the end of the

scale, the air was so foul that a match would not light, and it was extremely

difficult to breathe. She had spent more than 28 hours under water making good

75 miles.

Cowan was understandably angry with Curtis when he learned

how the loss of the Vittoria had occurred, but his remarks on the report of the

subsequent court of inquiry so far recognised the good work which the Twentieth

Flotilla was doing that Curtis escaped with no more than Their Lordships’

severe displeasure.

The British force suffered another loss four days later: the

Verulam, Lieutenant-Commander G. L. Warren, struck a British mine off Stirs

Point and sank with the loss of twenty-nine of her crew. But she belonged to

Maclean’s Second Flotilla which, to quote Cowan, “has scarcely yet become

accustomed to the difficult conditions of maintaining the patrols under the

cramped conditions of manœuvring space which must obtain whilst we remain

here.” The rest of September passed with few incidents in the Gulf worth

specific mention. Minelaying by the British ships was abandoned in the middle

of the month when the Princess Margaret and half the Twentieth Flotilla

returned to England, Curtis taking the remainder of his ships down to Libau to

augment Duff’s force. The Second Flotilla maintained the necessary regular

patrols and continued bombarding the southern shore. Extracts from a diary kept

by a member of the crew of the Westminster show what this involved:

With Vectis, Walpole and Valentine, left harbour, Walpole

and selves making straight for the Estonian coast. Our duties are to patrol the

flank of the troops ashore. Bolshevik forts are plainly to be seen, but make no

effort to fire at us. During the afternoon an Estonian destroyer suddenly made

a quick dash right in under the land, loosed off a few salvoes and as quickly

nipped out again. No reply from the shore to this greeting. . . .

With Walpole off Estonian coast; at 1645 Walpole opens

fire on battery ashore, keeping up 4-inch shell fire for half an hour or more.

Battery returns an accurate fire but falling short. Walpole must be anchored

just out of range. Walpole gets under way and, moving along the coast, opens up

a fine bombardment with all guns on what appears to be a factory with tall

chimney. We could see the fall of shot and the firing was very good. Walpole

had further gun practice later but we left the area to escort E39 to patrol

area. . . .

Spenser signals coming out at 0600 to assist bombardment.

We again escort E39, then join up with Spenser and Walpole. At 1045 we closed

up at action stations to do a little bombarding on our own account. Spenser

ceased fire but Walpole continued until Westminster opened up. Shore guns now

turned from Walpole on to us. They gradually got our range but fall of shot was

well astern of us. We opened fire at 11,000 yards and selected the tall chimney,

which was apparently being used as an observation post. We found the range as

10,800 yards and claimed some hits though the chimney still stood. After a

final 12 rounds of lyddite we returned to patrol.

The British cruisers, of which the Danae had been relieved

by the Phaeton, had nothing so interesting to occupy them. “It’s very boring

being here now,” noted the Cleopatra’s navigator. The depot ship Maidstone,

Captain Max Horton, reached Reval with a fresh submarine flotilla to relieve

the Lucia and Nasmith’s boats but this new blood was to have no opportunity for

action. Donald’s planes raided Kronstadt several times a week, usually with six

Camels, to some effect. And the Swedish Eskstuna III eluded the British

blockade of Petrograd with a cargo of handsaws, but was intercepted on her

return with a load of flax. Having orders to turn back neutral ships

approaching from the west, but no authority to seize one if it came from the

east, Cowan solved the problem by handing her over to the Finns. The Admiralty

appreciated that this was unsatisfactory and pressed the Foreign Office to

obtain a clear ruling from Paris. As a result, on 10th October, 1919, the

Supreme Council announced a formal blockade of Petrograd which Cowan was

authorised to enforce notwithstanding its questionable legality, in that,

despite hostilities, war had not been declared between Britain and Soviet

Russia so that technically neither was a belligerent power.

From “the other side of the hill,” there is likewise nothing

of significance to record up to the end of September. Notwithstanding the

Pantera’s success, Zelenoy made no further attempt to attack Cowan’s force, or

to interfere with the support which it was giving to the Estonians in Kaporia

Bight. In the words of a Soviet historian, the British ships “had continuous

command of the Gulf,” a proper tribute to the work of Cowan and all who served

under him.

On land, in the same period, there was no advance—but there

were political developments. On 14th August Gough managed to form a Russian

North-West Government in Helsingfors with Yudenitch as Minister of War and

Commander-in-Chief. Gough’s reasons for this step, which was taken with

Tallents’s approval, were three; (a) the critical condition of the Russian

North-Western Army, (b) the seriousness of a threat by the Estonian Army to

refuse to participate further against the Bolsheviks unless Estonian

independence was granted and (c) the need to fuse democratic and reactionary

parties into a whole-hearted attack on the Bolsheviks. And this new Government

quickly displayed its willingness to co-operate by issuing a declaration

recognising Estonian independence and calling on the Allies to do likewise. For

this action, which London and Paris viewed as contrary to Allied policy, Gough

was recalled to report. He went under the impression that the German evacuation

of Latvia was progressing well, and that Bermondt had agreed to serve under

Yudenitch. Though he was mistaken in both these matters, the War Office did not

hesitate to issue a lengthy report summarising Gough’s work since his arrival

in June which expressed considerable satisfaction with all that he had achieved

in the face of many difficulties. No doubt this document was inspired by the

militant Churchill who had his own views on the need to recognise the

independence of the Baltic States. For on 20th September, 1919, he wrote to the

Prime Minister urging that this should be done at once, “for in a little while

it would be too late to secure terms for these small States which had given aid

against Bolshevism.” But with unusual frankness Lloyd George answered:

You want us to recognise their independence in return for

their attacking the Bolsheviks. (But) in the end, whoever won in Russia, the

Government there would promptly recover the old Russian Baltic ports. Are you

prepared to go to war with perhaps an anti-Bolshevik Government of Russia to

prevent that? If not, it would be a disgraceful piece of deception on our part

to give any guarantee to those new Baltic States that you are proposing to use

to conquer Russia. You won’t find another responsible person in the whole land

who will take your view, (so) why waste your energy and your usefulness on this

vain fretting?

Whilst all this was happening, the Bolsheviks, wishing to

divert their Seventh Army to help compass the early defeat of Kolchak’s and

Denikin’s forces, had decided to forego their claims to the Baltic States. They

were therefore encouraging overtures for armistices from both Estonia and

Latvia, with the result that Curzon instructed Grant Watson to request that the

Latvian Government “will take no action in the direction of peace. His

Majesty’s Government would deplore individual action being taken by them and

trust that they will conduct their foreign policy only as part of a concerted

plan with the Allied Governments.” Unfortunately the Allies had no plan—at

least none which recognised the Baltic States’ demand for de jure recognition.

However, on 25th September, Curzon sent an important document to Tallents:

The numerous requests for assistance and for a definite

declaration of policy that are continually addressed to H.M. Government on

behalf of the Baltic States, have required the former to reconsider the

question. It now appears that none of the States concerned wishes to act

separately, and that concerted action is contemplated. Indeed, a conference has

been summoned for this purpose on 29th September. H.M. Government have already

recognised the autonomous existence of the Baltic States, and have dealt with

them as such. The question of (their) de jure recognition is one which it is

impossible for them to decide upon their own responsibility. The Peace

Conference alone, or the League of Nations sitting in sequel to the Peace

Conference, can arrive at a definite decision. The principal menace by which a

settlement is threatened is the presence of German forces under Goltz. Foch has

already requested the German Government to order their immediate withdrawal,

and in view of their failure to comply, steps are being taken to apply measures

of coercion.

H.M. Government are asked whether they can continue to

supply military material and stores to the States. The reduction of the

available stocks consequent upon the termination of the war and the shortage of

shipping unfortunately renders this impossible. This is not intended to imply

abandonment of the States in the event of their existence (being) imperilled by

an invasion of Bolshevik forces. H.M. Government might (then) be prepared to

reconsider their decision as to the supply of war material. As regards the

provision of credit, it is impossible for H.M. Government to assume a financial

responsibility which they have hitherto been unable to accept. While they have

exerted themselves to aid the States in the provision of loans from independent

quarters, they cannot, in view of the grave financial straits in which the

entire world is placed, depart from their attitude in this respect.

In these circumstances H.M. Government feel that they are

not entitled to exercise any pressure upon the free initiative of the Baltic

States, and that their Governments must be at liberty to decide upon such

action as may be most conducive to the preservation of their own national

existence. It is for them to determine with unfettered judgment whether they

should make any arrangement, and if so of what nature, with the Soviet

authorities; and if, as seems to be in contemplation, they decide to act in

unison, the effective control of the situation should be within their power.

Of the likely outcome of the conference to which Curzon

referred, Horton noted: “All the Baltic States’ delegates, with the Finns as

well, are meeting to-day to discuss whether they are going to make a combined

peace with the Bolshies or not. I expect it will come off, for everyone seems

tired of scrapping and the conditions are certainly damnable.” But he forgot

Goltz, of whose return to Mitau after a visit to Berlin to ensure that the

Weimar Government supported his plans for Latvia, Cowan had recently written

that it “makes the German situation very serious, and if the Allies persist in

allowing this officer to defy them and go where he likes in the Baltic, there

can never be any satisfactory solution to any question out here.”

#

Reverting to the middle of August, Duff in the Caledon at

Libau had the assistance of the Royalist, with destroyers from the Third

Flotilla and Brisson’s French sloops to help him at Windau and Riga—a force

which was augmented by Curtis’s Twentieth Flotilla in the middle of September.

Up to the end of that month these ships were not involved in any serious

incident: Duff and his captains were chiefly concerned to support Ulmanis’s

Government in the face of Goltz’s determination to achieve his own ends, and

the Allies’ failure to enforce his removal.

On the evening of 24th August (wrote Duff) the Germans held

a demonstration at Mitau against evacuating Latvia, asking Goltz to keep

command and to separate from the German Government. The Lettish garrison were

disarmed, their headquarters entered, and a safe pillaged. The Commander of the

(German) division addressed the demonstrators and signified that evacuation

would not be insisted upon. The German Command states that soldiers refused to

entrain owing to promises of land in Latvia. This has the appearance of carrying

out the policy that Goltz is reported to have threatened, viz. stating that he

can no longer control his troops; and, instead of evacuating them, to allow

them to break away and by pillage and destruction reduce the country to such a

state that it will be necessary for some organised armed force to occupy it.

And since Germany appears to be the only country that is ready to do so, and

will say that it is impossible to have Bolshevism on her borders, she will

probably reoccupy it.

Duff also noted that many Germans were joining Bermondt’s

growing force, whose leader publicly denied the Russian North-West Government’s

authority and, notwithstanding instructions which he received from Kolchak in

his capacity as Supreme Ruler of Russia, refused to obey Yudenitch’s orders,

from which it was clear that an advance on Petrograd was not his purpose.

In the middle of September the Supreme Council considered a

draft note which the French proposed should be sent to Berlin, once again

demanding evacuation of the Baltic States. If not complied with within a month,

steps would be taken to enforce it by economic restrictions, a renewal of the

blockade, stoppage of the repatriation of prisoners and, if necessary, force.

Foch declared that he did not believe this would have any effect: it amounted

only to a further postponement of the question. Gough, who was called to give

his views, stressed that the German danger was far more serious than the

Bolshevik. Goltz, he said, was plotting to form

a large German army outside Germany, in alliance with the

non-Bolshevik Russians, to seize the Baltic States and eventually Russia

itself. The liberty of those States would be destroyed and the independence of

Finland threatened. This German and Russian force might well become the most

powerful in Europe and be used against the Allies. The population of the Baltic

States was democratic, not Bolshevik, but it would rather be under the

Bolsheviks than under the Germans. He thought that these States should be

allowed to make peace with Russia if they wished. It was not true that the

German troops would not obey Goltz. It would be easy to oblige the Germans who

were with the Russian troops to rejoin their own corps in Germany, as, in the

absence of a German army in the Baltic States, they would be murdered if they

remained there. The German Government was waiting to see whether the Allies

were prepared to show firmness.

The British Representative 1 then reminded the Council

that it was Lloyd George who had urged the necessity of

getting the Germans out of the Baltic States. The original plan was to send an

ultimatum and back it up by military force, but it had to be discarded owing to

American opposition. The substitution of a threat of some undefined economic

action seemed so completely to alter the character of the measure contemplated

that I seriously doubted the wisdom of resorting to another ultimatum to the

three already sent. Apart from this I could not commit my Government to the

adoption of the coercive measures proposed. I anticipated great difficulties in

stopping the repatriation of our German prisoners, nor could I say whether H.M.

Government was prepared, or even in a position to reimpose drastic restrictions

on trade and intercourse with Germany, involving a renewal of the blockade. I

therefore suggested that the Conference should defer a decision so as to allow

each delegation to obtain from their Government a statement of the precise

measures which (it was) prepared to take. If we could agree on (these), I thought

the best course would be to take them at once instead of merely threatening.

However, notwithstanding Crowe’s realistic appraisal, the

Council, when they next met four days later, decided only to send Berlin a

strongly worded note demanding, under threat of sanctions, an immediate

evacuation of the Baltic States, this to include all Germans in Bermondt’s

corps. Three days later the Wilhelmstrasse replied that it was replacing Goltz

by Lieutenant-General Magnus von Eberhardt who would supervise the evacuation.

But once again, Goltz and Berlin were a step ahead of the Allies. Although the

“Prussian fox” ostensibly transferred his command to Bermondt, who had formed

his own West Russian Government in Mitau, he was not recalled from Latvia: he

remained there in the background manipulating both Eberhardt and Bermondt with

the intention of restoring Niedra’s puppet régime.

Such was the position on 28th September, 1919, when the

Dauntless arrived at Libau and, as Madden had suggested, Duff went home in the

Caledon for leave and rest. This left Curtis as British senior officer in

Latvian waters. Realising that the comparative quiet which prevailed there was

too uneasy to last, and that when the explosion came it would centre on Riga,

he took the Abdiel and two of his flotilla five miles up the Dvina to join the

French sloop Aisne in the centre of the capital so that he could be in the

closest possible touch with Tallents and Burt.

Meanwhile, in Lithuania, although a French Mission had fixed a provisional demarcation line in June intended to stop the Poles from enlarging their hold on the Vilna area, they had moved farther forward. This compelled Foch to intervene; in July he fixed a second line farther to the west which, for the time being, checked Polish aggression, though clashes still occurred. Notwithstanding this pre-occupation, Vold-maris’s Government had managed, despite German obstruction and refusal to supply equipment, to mobilise a force sufficient to launch an offensive in May against the Bolsheviks to the north of Vilna; and by the end of August these had been driven back nearly to the frontier. The greater part of the country remained, nonetheless, under German occupation. There was also a Lithuanian “Bermondt,” by name Virgolich: against the day when the Allies compelled Berlin to evacuate their troops, Goltz had encouraged him to recruit a force of Russian ex-prisoners of war, providing it with German instructors and equipment. And this had been swollen by German volunteers until it numbered 2000 men with modern arms and transport as ready as Bermondt’s corps to do Goltz’s bidding.

RUSSIAN BOLSHEVIK WATERS 1919