Contrary to both contemporary popular opinion and enduring

myth, Lee was hardly at his tactical best in the Seven Days, but he did reveal

himself as an inspiring commander with an ability to extract the utmost

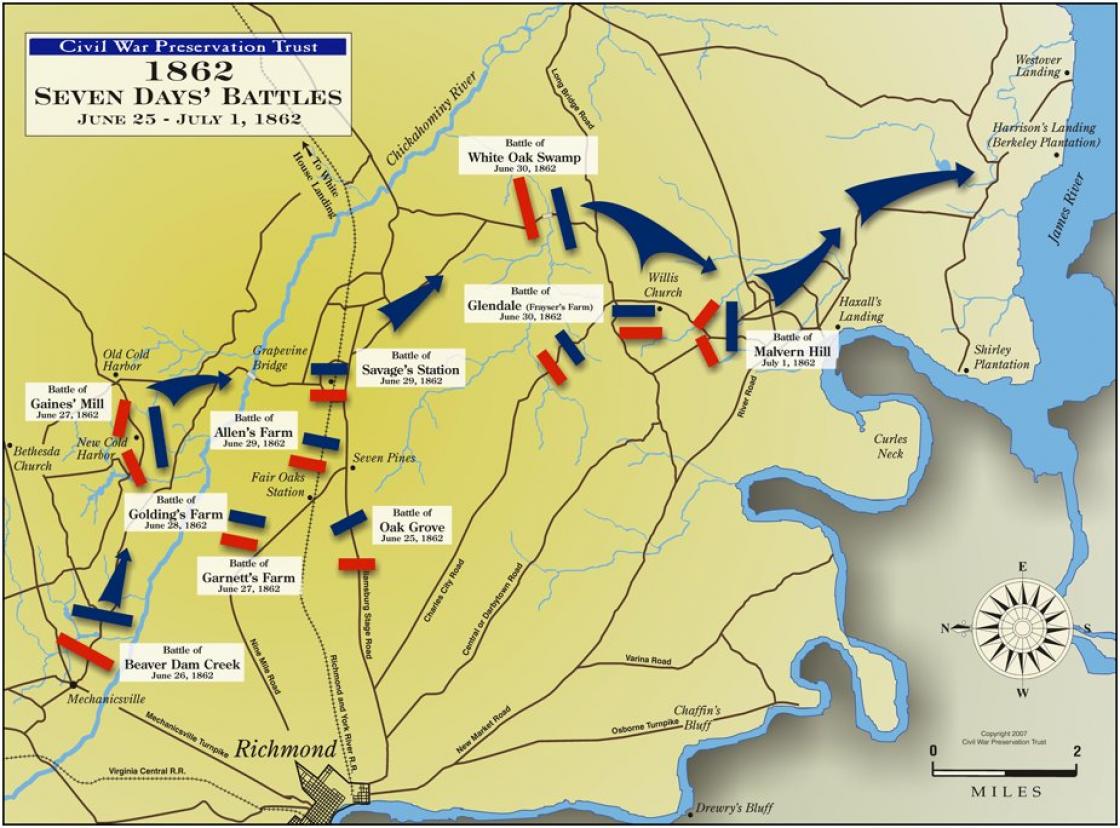

aggression from his men. The Battle of Oak Grove (June 25) ended inconclusively

and with relatively light casualties on both sides, but it put Lee in position

to seize the initiative on the following day at the Battle of Beaver Dam Creek

(Battle of Mechanicsville, June 26). While Lee suffered a tactical defeat—1,484

casualties versus 361 for the Union—he set up a major strategic triumph by

forcing McClellan to withdraw from the Richmond area.

The Battle of Gaines Mill (June 27) on the next day again

resulted in heavier losses for Lee (7,993 killed, wounded, missing, or

captured) than McClellan (6,837 killed, wounded, missing, or captured), but so

unnerved the Union general that he began the retreat of the entire Army of the

Potomac all the way back to his supply base on the James River. For his part,

Lee was not about to let him go. He engaged portions of the withdrawing Union

forces at Garnett’s & Golding’s Farms (June 27–28) before mounting a major

attack at the Battle of Savage’s Station (June 29), exacting more than a

thousand casualties. By noon on June 30, most of the battered Army of the

Potomac had retreated across White Oak Swamp Creek. Lee hit the main body of

the army at Glendale (June 30) while his subordinate Stonewall Jackson attacked

McClellan’s rearguard (under Major General William B. Franklin) at White Oak

Swamp (June 30). By the numbers, both engagements were inconclusive, but the

humiliating “optics” were incredibly damaging to the Union and just as incredibly

inspiring to the Confederacy. Lee was driving McClellan away, whipping him as a

man might whip a dog.

The final battle of the Seven Days, at Malvern Hill (July

1), was evenly matched, pitting 54,000 men of the Army of the Potomac against

55,000 of the Army of Northern Virginia. Lee suffered 5,355 casualties to

McClellan’s 3,214, but persisted in pursuing McClellan. Concluding that

McClellan was unwilling to use his army effectively against Lee, Lincoln

ordered him to link up with John Pope’s Army of Virginia to reinforce him at

the Second Battle of Bull Run (August 28–30, 1862).

It was at this battle that Lee revealed the tactical daring

absent from his action at the Seven Days. He attacked the Army of Virginia

before the slow-moving McClellan arrived in to consolidate with it his Army of

the Potomac. In this attack, Lee purposefully broke one of the supposedly

inviolable military commandments by dividing his forces in the presence of the

enemy. He sent one wing under Stonewall Jackson to attack on August 28. This

deceived Pope into believing that he had Jackson exactly where he (Pope) wanted

him. The Union general could taste victory. But, in fact, it was Jackson who

was holding Pope, so that Longstreet, leading Lee’s other wing, could launch a

surprise counterattack on August 30. This attack, 25,000 men brought to bear

all at once, was the single greatest mass attack of the Civil War, and it

brought about a second Union defeat at Bull Run that was far costlier than the

first. Pope lost 14,642 killed, wounded, captured, or missing. Lee lost half

that number.

The Second Battle of Bull Run made Robert E. Lee the general

to beat. Pope had been fired, and McClellan was recalled to lead the Army of

the Potomac against the ever-aggressive Lee, who had decided to take the war to

the North by invading Maryland. McClellan fought him at Antietam in that state

on September 17, 1862.

At the beginning of the Seven Days, the battle line had been

some six miles outside of Richmond. Three months later and thanks to Lee, it was

at Antietam, just twenty miles outside of Washington. At the end of the day,

McClellan had suffered heavier losses than Lee (12,410 to 10,316 killed,

wounded, missing, or captured) but he had forced Lee to withdraw back into

Virginia. President Lincoln used this narrow Union victory to launch his Emancipation

Proclamation, but, privately, he was bitterly disappointed—heartbroken,

really—that McClellan had failed to pursue the retreating Lee in the way that

Lee had earlier pursued the retreating McClellan.

Abraham Lincoln removed George McClellan from command of the

Army of the Potomac and replaced him with Ambrose Burnside—despite Burnside’s

own protests that he was not up to commanding a full army. At Fredericksburg

(December 11–15, 1862), Burnside proved his self-appraisal to be correct.

Although substantially outnumbered (78,513 to 122,009), Lee dealt Burnside and

the Army of the Potomac a catastrophic defeat, inflicting 12,653 casualties for

his own losses of 4,201 killed, wounded, or missing.

Lincoln replaced Burnside with Joseph “Fighting Joe” Hooker,

who proclaimed, “May God have mercy on General Lee, for I will have none.”

Hooker commanded an Army of the Potomac that now mustered nearly 134,000 men,

whereas Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia amounted to no more than 60,298.

Lopsided though the numbers were, the Battle of Chancellorsville (April 30–May

6, 1863) was Lee’s tactical masterpiece—arguably the tactical masterpiece of

the Civil War itself. Once again, Lee divided his forces in the presence of the

enemy, dispatching his cavalry to control the roads and bottle up Union

reinforcements at Fredericksburg while 26,000 men under Stonewall Jackson

surprised Hooker’s flank even as he, Lee, personally commanded a force of

17,000 against Hooker’s front. The result stunned the Union general into utter

confusion. Jackson’s surprise attack routed an entire corps and drove the

principal portion of Hooker’s army out of its well-prepared defensive

positions. By May 2, the Army of the Potomac, though it outnumbered the Army of

Northern Virginia two to one, had been sent into headlong retreat.

Yet Lee understood that he was in no position to bask in his

triumph, great as it was. Hooker had suffered 17,287 casualties, but he himself

had lost 13,303 killed, wounded, captured, or missing—all out of a much smaller

force. Hooker’s casualty rate was roughly 13 percent, whereas his own was a

staggering 22 percent. Despite the victories he delivered, Lee was convinced

that the Confederacy could not endure such attrition much longer. He therefore

resolved to once again invade the North. This time, his objective was

Pennsylvania. Not only did he want to raid the countryside for much-needed

provisions, Lee believed a successful invasion would utterly demoralize the North

and erode its will to continue the war while also opening up an avenue for an

assault on Washington itself. This, he believed, would cost Lincoln reelection

and bring into office a Democrat willing to conclude a negotiated end to the

Civil War.

The grim fate of Lee’s aspirations for the Battle of

Gettysburg. Defeated badly here, Lee was nevertheless able to withdraw back

into Virginia, his army diminished but still very much intact. He would lead it

next against his most formidable adversary, Ulysses S. Grant, in the Civil

War’s culminating Virginia battles. In many of these engagements, Lee would, in

fact, beat Grant. But, unlike the other Union opponents Lee had confronted,

Grant responded to defeat not with retreat, but with continued advance toward

Richmond. Each advance forced Lee to pit his dwindling Army of Northern

Virginia against Grant’s continually reinforced army. The Union general

understood and embraced the ultimate calculus of the Civil War, which was that

the North could afford to spend more lives than the South and could replenish

most of its losses.

Lee’s objective in the final months of the war was to make

his own increasingly inevitable defeat so costly to the Union that the people

of the North might demand a negotiated settlement after all. Costly he did make

it, but, in the end, Robert E. Lee felt compelled to admit defeat. In this

admission was perhaps the most profound and enduring significance of his

elevation to top command of Confederate forces. For as he had been

uncompromising in his quest for victory, so he proved equally uncompromising in

his manner of surrender. He secured from Grant the best terms possible, namely

the right of his men to return to their homes unmolested and without loss of honor.

In return for this, he exercised his character and influence to ensure that the

war would in fact end rather than devolve into a long and lawless guerrilla

struggle, which is the fate of so many civil conflicts throughout history.