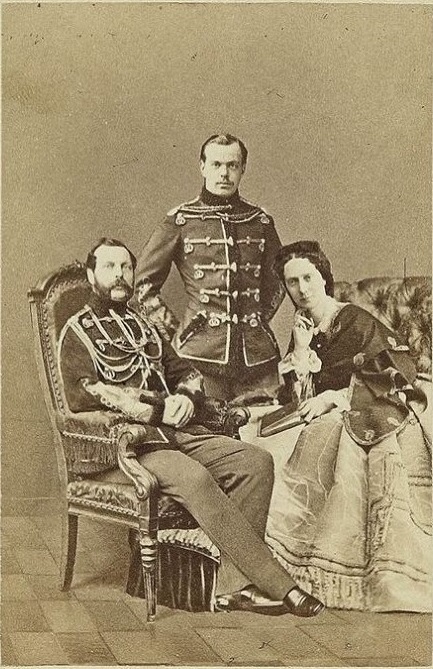

Emperor Alexander II and his wife, Empress Maria, with their son, the future Alexander III by Sergei Lvovich Levitsky 1870

Alexander II, who would one day be known as Alexander the

Liberator, was crowned on August 17, 1856. He ascended the throne on the eve of

Russia’s defeat in a hastily prosecuted war in Crimea; his first task as the

new emperor was to get them out of it. Turning to France, he offered to

negotiate a peace; the French demanded that Russia withdraw its ships from the

Black Sea. It was the greatest loss the Romanov dynasty had ever known, but

Alexander absorbed the blow to his pride. His attention was soon taken up with

a more consuming project.

The glory of Alexander II’s reign was the freeing of the

serfs. Since the days of tsar Alexei, serfs had been no better off than slaves.

Nobles could not kill their serfs outright, but they could punish them so

severely that death was the inevitable consequence. Serfs could not leave the

estates where they were born, nor could they marry or own property. Serfs were

themselves property. An emperor who wished to reward one of his nobles would

dispense that reward in the form of rubles and “souls”—that is, human beings,

serfs. Ninety percent of the Russian population were serfs, and serfs composed

almost all of the army. Every emperor since Catherine the Great had looked for

a way to free the serfs without destroying the Russian economy or sparking mass

riots in the process, and all had abandoned the project while it was

incomplete. But Nicholas I had made Alexander promise to do it on his

deathbed—a strong motivation for success. The dying emperor had also extracted

a promise from Elena Pavlovna, wife of Nicholas’s brother Michael, nicknamed

“the Family Intellectual”, to help Alexander figure out how to do it. The new

emperor would need all of her help.

He began on March 30, 1856, when, after informing the upper

classes of Moscow that he intended to end serfdom, he instituted the Secret

Committee on Peasant Reform. The chief difficulty was the entrenched resistance

of the nobility, who were unwilling to relinquish their right to hold the same

sway over other human beings that the tsar held over them. The next greatest

difficulty centered around land. It was not enough to declare that serfs were

free; they must have somewhere to live and a means of making a living. In 1858,

Alexander and his empress made a tour of the countryside, visiting nobles who

lived at a distance from Moscow and chastising them for not falling into line

quickly enough. By 1861, the work was done. Alexander signed his decree in the

presence of his brother, the liberal intellectual and reformer Konstantin

(called Kostia), and his son and heir Nicholas (Nixa). No one knew what to

expect; revolution was a possibility. Cannon were lined up outside the Winter

Palace, just in case. But no uprising came. With the stroke of a pen, Alexander

II had given to twenty-two million of his people the right to marry, to buy and

own property, to leave the estate they were born on, to seek education. They

still cultivated the land, but they could no longer be bought and sold. All the

souls of Russia were now free.

Reform was the theme of Alexander II’s reign, along with the

hope that reform engenders in a rigidly traditional society. Under Alexander I

and Nicholas I, any hint of liberalism had been rigidly repressed, for fear

that the anti-monarchial spirit that enflamed France during the revolution

would spread to Moscow and St. Petersburg and undermine the war effort. Now

that the tsar was establishing an independent judiciary and creating

representative assemblies at the local government level (a greater degree of

agency than any tsar had ever given to the Russian people) a spirit of

rebellion was brewing in the so-called Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, which

was composed of modern-day Poland, Lithuania, Belarus, Latvia, parts of

Ukraine, and western Russia. Alexander responded to this rebellion by sending

his younger brother Kostia to be viceroy of Poland. A full-scale revolt, known

as the January Uprising, broke out when Kostia began conscripting Polish boys

into the Russian army. It was quickly suppressed, but Alexander’s ministers

began to blame the tsar’s moderate tendencies for allowing civil unrest to

breed. Under Nicholas I, poets, novelists, playwrights, university students and

faculty, and other artists and intellectuals had been subject to strict

government censorship. Alexander II had lessened these restrictions, and a

radical element had arisen as a result. His reforms had given birth to a new

element in society, the intelligentsia, made up of people who were poor and

lower class but well-educated. Alexander punished them for writing radical

articles in the newspapers, but they were not the heavy-handed punishments of

his predecessors. Many jailed writers continued to write in prison.

The son and heir of Alexander II was Nicholas, called Nixa

by his family. Nixa was regarded as the perfect heir, rather as his father had

been. He was handsome, intellectual, independent, daring, and a model student

for his tutors. As a very young man, he had taken a shine to Princess Dagmar,

daughter of the King of Denmark, whom he had never met—it was her photograph

that attracted him. In 1864, when he was almost twenty-one, Nixa traveled to

Denmark, which had recently been defeated in a war against Prussia and Austria.

His fancy for Dagmar, called Minny, turned to love when he met her in person.

But shortly after their meeting, Nixa was diagnosed with cerebrospinal

meningitis. He died in Nice, surrounded by Minny and his family, who had rushed

to Europe to be with him. His twenty-year-old brother Alexander, called Sasha,

was now heir to the Russian throne. Sasha had been devoted to Nixa, but he was

unlike him in every way. Nixa had been slight; Sasha was huge. Nixa was

intelligent and intellectual; Sasha was narrow-minded, traditional, and bad at

foreign languages. Courtiers compared him to a peasant in his coarseness.

If Nixa was among the best-prepared of the Romanov heirs,

Sasha was among the least prepared, even by the standards of younger brothers

who unexpectedly move up in the line of succession. To give him credit, he was

aware of his shortcomings. He worried that he did not have the judgment to tell

an honest man from one that was merely ambitious and flattering. A further

difficulty soon presented itself. The emperor and empress had become extremely

fond of Minny, and it was their wish, as well as the wish of Minny’s parents in

Copenhagen, that she now marry Sasha. As for Sasha, he had been impressed by

Minny and admired her for her outstanding qualities, but he was in love with

one of his mother’s maids of honor. Alexander II was angered by his

stubbornness, and Sasha, who felt unfit for the throne, contemplated renouncing

his claim on the succession. Nonetheless, he married Minny on October 28, 1866.

After their marriage, he fell in love with her in earnest. Their first child

was born on May 6, 1868. Named for his grandfather, he would grow up to become

emperor Nicholas II, the last tsar of Russia.

Earlier in 1866, a young radical named Dmitri Karakozov had

lain in wait for the emperor near the Summer Garden, where Alexander walked

daily in the company of his eighteen-year-old mistress Katya Dolgoruky. There,

every afternoon, they paraded in full view of the admiring residents of St.

Petersburg. Karakozov had fired his pistol at the emperor as he boarded his

carriage, but the shot went astray and Karakozov was arrested. Alexander’s

reaction to the assassination attempt was to tighten restrictions on the

liberals in his ministries, and to strengthen the Third Section, the tsar’s

secret police. But radical factions only grew in strength and numbers. Then, in

1867, while Alexander was visiting the World Fair in Paris at the invitation of

Napoleon III, a young Polish man fired two shots at the emperor while he rode

in an open carriage with his sons. Alexander escaped unscathed, and this man

too was arrested.

In 1877, Alexander II declared war on the Ottoman empire in

support of an Orthodox uprising in Bosnia-Herzegovina, backed by Serbia and

Montenegro. The Russian people rallied to the cause of supporting their

“brother Serbs” with a nationalistic enthusiasm not seen since Napoleon’s

invasion in 1812. The Ottomans were slaughtering Orthodox Christians in

Bulgaria, but Alexander was forced to respond slowly, because the British were

adamantly opposed to Russia regaining any of the Crimean lands it had conceded

after the disastrous ending of Nicholas I’s war. Russia, however, was backed by

the new German empire, which, under the leadership of Otto von Bismarck, had

taken advantage of Russia’s cooling relations with Austria to unify the German

states under Kaiser Wilhelm I and march on Paris.

Despite inept leadership, it seemed possibly by December of

1877 that Russia would take possession of the cherished prize of Constantinople

at last. But the British, fearing this outcome above anything, deployed their

navy in the Black Sea and threatened to enter the war on the Ottoman side. A

stand-off ensued, only ended by a conference between the European powers in

Berlin, which, among other things, awarded Russia control of part of Bulgaria.

By the time matters had been settled in late 1878, Alexander was exhausted and

beginning to feel his advanced middle age.

The revolutionary element in Russia was gaining momentum. In

1878, the governor of St. Petersburg was shot by a woman named Vera Zasulich,

in full view of multiple witnesses. A jury trial exonerated her, however,

because Zasulich’s attack had been motivated by the cruel treatment of

political prisoners. Alexander was infuriated, and ordered that she be arrested

again, but she escaped Russia before she could be re-apprehended. Her acquittal

was a sign of the times. Assassinations and assassination attempts were carried

out against other high ranking officials. In April of 1879, the emperor was

nearly shot while out walking—the third assassination attempt he had survived.

In 1879, Sofia Perovskaya, one of the leaders of a terrorist group that called

itself Land and Freedom, made a fourth attempt on Alexander’s life by bombing

the train he was traveling in. Then, in February of 1880, a servant at the

Winter Palace, Stephen Khalturin, smuggled three hundred pounds of

nitroglycerine into the palace, with the goal of bombing the tsar and his whole

family as they sat down to dinner. When Khalturin detonated the charge,

Alexander and his family were unharmed, but a large number of guards and

sentries were killed.

Alexander’s response to the bombing of the Winter Palace was

extraordinary. The reactionary heir, Sasha, insisted that he form a Supreme

Commission, the head of which would be endowed with the powers of a dictator,

to root out the terrorist cells. Alexander did so, but the man he placed at the

head of the commission, Mikhail Loris-Melikov, was an unusually broadminded

thinker. His goal was to root out, not only terrorism, but the causes of

terrorism—such as censorship, judicial corruption, and high taxes. He fired the

repressive minister of education and limited the powers of the secret police.

These measures were partly successful, but the unrest continued.

In May of 1880, the Empress Marie, who had suffered from

tuberculosis for many years, died in her sleep. Alexander had long ago promised

his mistress, Katya Dolgoruky, that he would marry her if he were ever widowed.

They were accordingly married in a private ceremony in July. Katya became Her

Most Serene Highness, Princess Yurievskaya, but she was treated coldly by

Alexander’s family.

In January of 1881, Alexander began working with

Loris-Melikov on a series of reforms that would pave the way towards a Russian

constitution. He intended to announce it before the public on the same day that

Yurievskaya was to be crowned empress, March 4, 1881. But on March 1, on his

way home to the palace after reviewing a parade of Guards, Alexander II at last

fell victim to an assassination attempt organized by Sofia Perovskaya. A bomb

was detonated under the carriage Alexander was riding in. The emperor was

unhurt, but several people, including one of his bodyguards, a policeman, and

two bystanders, had been wounded. The young man who threw the bomb was arrested

immediately. Rather than fleeing the scene, Alexander went to inspect the

remains of his carriage, when a second bomber rushed towards him. The explosion

mortally wounded the emperor, the bomber, and injured others. Alexander’s legs

were shattered; he was rushed home to the Winter Palace, where his family,

having heard the explosions in the distance, were waiting anxiously.

The deathbed of Alexander II—the most moderate,

compassionate ruler of the Romanov dynasty—was unrivaled in the family’s

history for its tragic quality. The ruined body of the emperor clung to life

long enough for last rites to be administered and for his family to witness his

departure. His wife, Princess Yurievskaya, clung to his body until her

nightgown was soaked with blood. When he drew his final breath, those present

in the room saw a change settle over his thirty-six-year-old son, now emperor

Alexander III. As heir to the throne, he had been compared to a peasant for his

coarse humor and manners. Now, suddenly, he seemed to grow grave, as the burden

of the throne came to rest on his shoulders. His entire reign would be a

reaction to the brutal assassination of his father