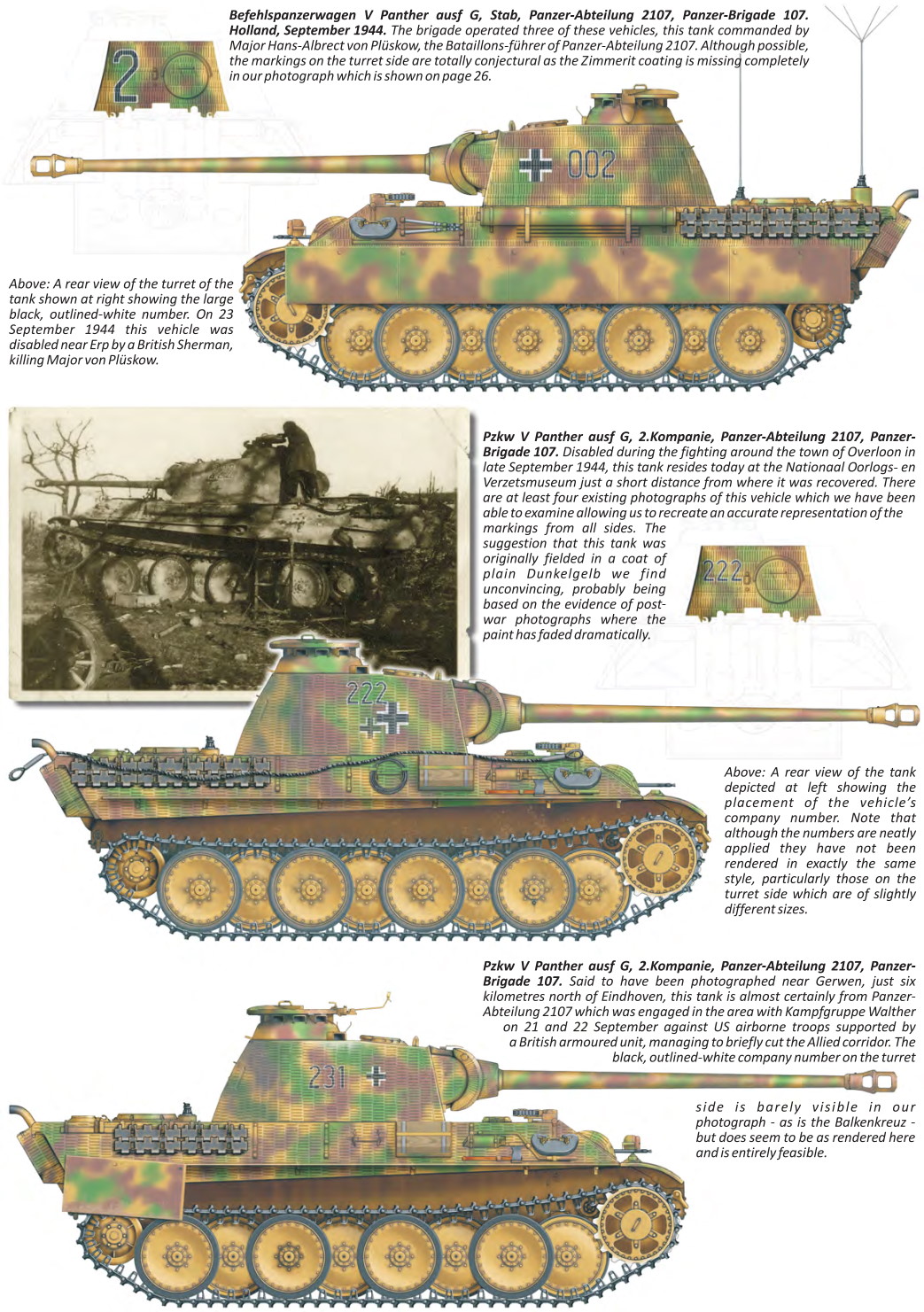

During the autumn of 1944, in the aftermath of the failed

attempt on Hitler’s life on July 20, and in the aftermath of the Red Army’s

colossal breakthroughs in the East, the Nazi regime and the German people

mobilized their last reserves of ferocity and fanaticism. The propaganda vision

of a people’s community at arms and the free rein given to violence on both

foreign and home fronts enhanced a pattern of exploitation and dehumanization

already permeating German society from the factories to the countryside.

Rationality gave way to passion and to fear as retribution loomed for a

continent’s worth of crimes.

The Wehrmacht went out fighting and it went down hard. Like

the German people, it neither saw nor sought an alternative. The prospective

fate implied in the Allies’ demand for unconditional surrender could assume

terrifying form to men who had seen—and participated in—the things done “in the

name of the Third Reich and the German people.” That meant reconstructing

shattered divisions by placing officers at road junctions and impressing every

man without a clear destination, even if cooks became tankers and sailors found

themselves in the Waffen SS. It meant filling out ranks with teenage draftees

and men combed out of the increasingly moribund navy and air force. It meant

reequipment by an industrial system that continued to defy the best efforts of

the Combined Bomber Offensive. It meant morale enforced by laws making a

soldier’s family liable for any derelictions of duty. It meant field

courts-martial that seemed to impose only one sentence: death.

Combine Eisenhower’s commitment to a continuous front with

the relative weakness of Allied ground forces, and weak spots must inevitably

emerge. The most obvious one was in the American sector: the Ardennes Forest, a

static sector manned by a mix of green divisions and veteran outfits that had

been burned out elsewhere. Hitler’s intention, shared and underwritten by High

Command West, was to replicate the success of 1940 by striking through the

Ardennes for Antwerp. The port’s capture would both create a logistical crisis

for the Allies and divide the British from the Americans, opening the way to

their defeat in detail and—just possibly—to a decisive falling-out between

partners whose squabbling, egalitarian relationship was never really understood

by German strategic planners who believed in client systems rather than

alliances.

That the Allies still had absolute control of the air over

the front, and that German fuel supplies were about enough to get their tanks

halfway to Antwerp, did not concern the Führer. Nor were his generals

excessively disturbed. The planners of High Command West preferred in principle

a more limited operation: a double envelopment aimed at Liege. They were,

however, never able to convince even themselves why Germany’s last reserves

should be used that way. What was to be gained, except a drawn-out endgame?

At least the West was geographically small enough to offer

something like a legitimate strategic objective. The Eastern Front presented

only the prospect of a second Kursk, with the last of the panzers feeding

themselves into a Russian meat grinder somewhere east of the existing front

line. Panzer Lehr’s Fritz Bayerlein echoed many of his counterparts when he

said he persuaded himself that the attack would succeed in order to give his

orders credibility and sustain the aggressive spirit of his subordinates. If

Operation Watch on the Rhine proved a Twilight of the Gods, then it would be a

virtuoso performance as far as the army’s professionals and the zealots of the

SS could make it.

By mid-December a buildup overlooked or discounted by

confident Allied commanders gave the Germans a three-to-one advantage in men

and a two-to-one advantage in armored vehicles in their chosen sector of

attack. A new 6th SS Panzer Army had been organized in September under Sepp

Dietrich. By this time in the Western theater the distinctions and antagonisms

between army and Waffen SS had diminished, especially in the panzer formations,

where the consistently desperate situation and the relatively even numbers of

divisions made close mutual support a necessary norm. In the projected

offensive, 5th Panzer and 6th SS Panzer Armies would fight side by side with

few questions asked.

Part of the army panzers’ reconstruction involved

reorganization. Both in Russia and in the West, the events of 1944 had resulted

in serious losses of trained specialists and no less serious discrepancies

between the numbers actually available in the combat units and those in the

divisions’ rear echelons. One response was pairing panzer divisions by twos in

permanent corps that would assume service and training responsibilities. Five

were organized and saw action, against the Russians in the final campaign. More

significant was the introduction on August 11 of the Panzer Division Type 1944.

This gave each panzer grenadier regiment an organic pioneer company and each

tank battalion organic maintenance and supply companies. Both changes

acknowledged the decentralization that had become the panzers’ tactical and

operational norm. Battalions consistently shifting rapidly from place to place

and battle group to battle group would now be more self-sufficient. Divisions

would now be better able to concentrate on planning and fighting—at least in

principle.

The new panzer divisions were still authorized two tank

battalions, each of as many as 88 tanks. Paper may be infinitely patient;

reality is less forgiving. In the autumn of 1944, Allied heavy bomber strikes

repeatedly hit most of the big tank manufacturing complexes: Daimler-Benz, MAN

in Nuremberg, and the Henschel Tiger II plant in Kassel. Speer was able to

sustain production, but only around half of the 700 Panthers and Panzer IVs scheduled

for delivery in December reached the intended users.

The shortages also reflected decisions made in the Armaments

Ministry. Speer had kept up tank production by transferring resources from the

manufacture of other vehicles and by cutting back on spare parts. The latter

dropped from over a quarter of tank-related contracts in 1943 to less than 10

percent in December 1944. Critical resources, like the molybdenum that made

armor tough as opposed to brittle, were in critically short supply. Quality

control slipped badly in everything from optics to transmissions to welding.

The continued willingness of Germans to report for work despite the bombing is

often cited. The on-the-job efficiency of men and women deprived of everything

from their homes to a night’s sleep has been less investigated.

The increasing use of slave labor in war plants had

consequences as well. Distracted, tired foremen and overseers were easier to

evade. Risks that seemed foolhardy in 1943 took on a different dimension as the

Reich seemed on the edge of implosion. Deliberate sabotage was probably less

significant than hostile carelessness. But increasing numbers of panzers were

coming on line with screws poorly tightened, hoses poorly connected—and an

occasional handful of shop grit or steel filings deposited where it might do

some damage. That was no small matter in contexts of frequently inexperienced

crews and frequently nonexistent maintenance vehicles.

The immediate response was to reduce the number of tanks in

a company to 14, and where necessary to replace those with assault guns of

varying types. Even with these makeshifts, 15 panzer divisions still had only

one tank battalion. Sometimes an independent battalion would be

attached—Leibstandarte, for example, benefited by receiving the Tigers of the

501st SS as its de facto second battalion. Other divisions found themselves

with new battalions equipped with Jagdpanthers or Jagdpanzer IVs, trained for

antitank missions rather than tank tactics, or in the close cooperation with

panzer grenadiers that remained the assault guns’ mission in an offensive.

Training and equipment were general problems in divisions

preparing for the Ardennes offensive. Panzer Lehr, the army’s show horse, had

its full complement of men, a third tank battalion equipped with assault guns,

and one of the supplementary heavy antitank battalions. Das Reich, however,

reported a large number of inexperienced recruits, and reported individual and

unit training as at low standards. Leibstandarte described morale as excellent,

but combat readiness above company level as inadequate. The 116th Panzer

Division was short of armor, motor vehicles, and junior officers and NCOs.

Second Panzer Division lacked a third of its vehicles: on December 14, one

panzer grenadier battalion was riding bicycles. It was all a far cry from the

spring of 1940.

In its final form, Watch on the Rhine6 incorporated three

armies deployed on a 100-mile front under Model, commanding Army Group B since

Rundstedt had been restored, at least nominally, to his former position in

September. The balance of forces at the cutting edge, and their missions,

demonstrated the army’s decline relative to the Waffen SS. Dietrich’s 6th SS

Panzer was the spearhead, with Leibstandarte, Das Reich, Hohenstaufen, and

Hitler Jugend as its backbone, and five army infantry divisions as

spear-carriers and mop-up troops. Fifth Panzer Army would cover Dietrich’s

left, and Manteuffel had the army’s armored contribution: Panzer Lehr, 2nd and

116th Panzer Divisions, plus four infantry divisions. Protecting his left flank

in turn was the responsibility of 7th Army, with four infantry divisions and no

armor to speak of.

Watch on the Rhine’s order of battle incorporated 200,000

men, 600 armored vehicles, almost 2,500 supporting aircraft—that number itself

a triumph of concentration involving stripping the Reich’s air defenses. Radio

silence was draconically enforced. Camouflage was up to Eastern Front

standards. Parachute drops and sabotage units were expected to confuse

surprised defenders even further. The offensive seemed structured to maximize

what the Germans—the panzer troops in particular—considered their main

strength: sophisticated tactical and operational expertise.

Model could in principle call on another ten divisions, but

only two were panzers; the offensive would rise or fall with its starting

lineup. The operational plan was Sichelschnitt recycled. Dietrich, at the

Schwerpunkt, was to break through around Monschau, cross the Meuse around

Liege, and strike full tilt for Antwerp. Manteuffel would cross the Meuse at

Dinant and aim for Brussels. The panzers were expected to be across the Meuse

before the Allies could move armor sufficient to counter them.

As so often before, however, German focus devolved into

tunnel vision. None of the specific plans addressed the subject of Allied air

power. The responsible parties similarly avoided addressing directly the fuel

question. By comparison to the Western campaign’s early months, fuel supplies

were impressive, but the Panthers and Tigers were always thirsty. Were the

Americans likely to be so confused, so feckless, and so obliging as to leave

their fuel dumps intact as refilling points? In the climate of December 1944,

asking such a question suggested dangerous weakness of will and character.

Sepp Dietrich might be an unrefined, unimaginative,

hard-core Nazi, but he did not lack common sense. All the Waffen SS had to do,

he later said sarcastically, was “cross a river, capture Brussels, and then go

on to take Antwerp . . . through the Ardennes when the snow is waist-deep and

there isn’t room to deploy four tanks abreast let alone armored divisions. When

it doesn’t get light until eight and it’s dark again at four—and at Christmas.”

Sixth SS Panzer Army had four days to reach the Meuse. Dietrich and his staff

set the infantry divisions to breach US defenses on day one, December 16. When

the hastily reconstituted army units faltered in the face of determined

American resistance, the word was “panzers forward.” But Kharkov and Kursk were

a long way back. The Waffen SS had made its recent reputation in defensive

fighting. Experience in offensive operations had been diluted by expansion.

Officer casualties had been heavy. From battalion to division, 6th SS Panzer

Army correspondingly eschewed finesse in favor of head-down frontal attacks.

Tactical maneuver was further restricted by rain

periodically freezing into snow as temperatures hovered in the low thirties.

Fields already saturated by the heavy rains of early autumn turned into

glutinous paste when the heavy German tanks tried to cross them. The

alternative was straight down the roads and straight down the middle from

village to village. Each attack was expected to put the finishing touches on an

enemy that seemed on the ragged edge of breaking. Yet the “Amis” held on—and

without the fighter-bombers grounded by the same weather that slowed the

panzers.

For the sake of speed the SS neither used their

reconnaissance battalions to probe for weak spots, nor their pioneers to assist

the tanks. The tanks repeatedly pushed ahead and just as repeatedly lost

contact with their infantry, only to run afoul of ambushed Shermans and M-10s,

or bazooka teams taking advantage of relatively weak side armor. Even the 57mm

popguns of the infantry’s antitank units scored a few kills. The panzer

grenadiers, many of them half-trained recruits or converted sailors and airmen,

were at a surprising disadvantage against American regiments, some of which had

been in action since Normandy.

The 12th SS Panzer Division, on the German right, lost most

of its Panthers in the first two days and made no significant progress

thereafter. Its neighbor, Leibstandarte, similarly held up, responded by

sending forward an armor- heavy battle group. It included most of the

division’s striking power: a battalion each of Panthers, Panzer IVs, and Tiger

Bs: together around 100 tanks, a mechanized panzer grenadier battalion,

pioneers, and some self-propelled artillery. Its commander was

Lieutenant-Colonel Jochen Peiper. He had been Himmler’s adjutant from 1938 to

1941 and had enjoyed the Reichsführer’s mentoring and patronage. He had

developed into a hard-driving, charismatic risk-taker whose men followed him in

good part because of his reputation as someone who led from the front and was

the hardest man in any unit he led. Peiper was, in other words, an archetype of

the kind of officer the Waffen SS nurtured in Russia and now turned loose in

the West.

Peiper was also just the man to throw the dice for an entire

panzer army. His mission was to reach the Meuse, capture the bridges before

they were demolished, and hold until relieved. It was 100 miles over

back-country roads that were little more than trails. Orders were to avoid

combat when possible, and to tolerate no delays. The battle group’s movements were

a model tactical exercise—at first. The panzers bypassed confused American

rear-echelon troops, slipped between elements of American convoys, and overran

American supply dumps. With his fuel low, Peiper refilled his tanks with 50,000

gallons of US gas captured without firing a shot.

The panzers captured a key bridge at Stavelot on December

18, and pushed through to the Amblève River. All they had to do was cross, and

the way to the Meuse would be open. But an American engineer battalion blew the

bridges Peiper was expecting to rush—in one case literally under the gun of a

Tiger VIB. American tanks and infantry, moving faster than expected, retook

Stavelot and cut the panzers’ line of communication. The sky was clearing, and

the fighter-bombers returned to hammer Peiper’s columns relentlessly. The

battle group was down to three dozen tanks, as much from breakdowns as from

combat loss. Its infantry, exposed to the weather day and night in their

open-topped half-tracks, on cold rations and broken sleep, were numb with cold

and fatigue. Peiper requested permission to withdraw. It was refused. Relief

attempts were stopped almost in their tracks. As the Americans closed in,

Peiper made his stand at a village called La Gleize. After two breakout efforts

failed, with his tanks out of fuel and his ammunition exhausted, on Christmas

he led out on foot the men he had left. Moving by night, 800 survivors of the

6,000 who began the strike a week earlier made it back to Leibstandarte’s

forward positions.

Peiper left behind about 100 of his own wounded and another

150 American POWs. The senior US officer later reported that the Germans had

appropriately observed the rules of war. But from the operation’s beginning,

Kampfgruppe Peiper and the rest of Leibstandarte had left a trail of bodies in

its wake: as many as 350 Americans and well over 100 Belgian civilians. The

consequences were epitomized by the GIs bringing in some prisoners from

Peiper’s battle group who asked an officer if he wanted to bother with them. He

said yes. Not everyone did. For the rest of the war it was not exactly open

season on Waffen SS prisoners, but they surrendered at a higher degree of

immediate risk than their army counterparts.

Pieper was not necessarily a liar or a hypocrite when he not

only insisted at La Gleize that he did not shoot prisoners, but seemed

surprised by the allegation. He is best understood as resolving a specific form

of the cognitive dissonance that increasingly possessed the Wehrmacht in

particular and the Reich as a whole. The question of whether someone, Peiper or

a superior, somehow either gave orders to take no prisoners or made it clear

that “no delays” was a euphemism for “no prisoners” is misleading. Since

Normandy, a pattern had developed in which both sides processed refusing

quarter, shooting prisoners, and similar frontline atrocities, as mistakes,

misunderstandings, or part of “the filth of war”: fear, frustration, vengeance,

the semi-erotic thrill of having an enemy completely at one’s mercy.

Inexperienced troops are more prone to be trigger-happy, and

there was ample inexperience on both sides of the line in June 1944. Even a

thoroughly ideologized German was likely to see a difference between more or

less Aryan “Anglo-Saxons” and despised, despicable Slavs. Nor was there much to

gain by making things worse than they had to be. Within the same few days in

Normandy, elements of the Hitler Jugend murdered Canadian prisoners in cold

blood, and other troops of the division negotiated a local truce with a British

battalion enabling both sides to bring their wounded to safety. Such agreements

were not everyday occurrences, but they did happen. An officer of 9th Panzer

Division describes one of his men bringing a wounded American back to his own

lines and returning laden with chocolate and cigarettes as tokens of

appreciation. A story improved in the telling? Perhaps. But nothing similar was

plausible even as a rumor in the East. And one Russian Front was bad enough.

What did transplant from the East was a frontline culture that

since 1941 had developed into something combining convenience and indifference,

embedded in a matrix of hardness. Hardness was neither cruelty nor fanaticism.

It is best understood in emotional and moral contexts, as will focused by

intelligence for the purpose of accomplishing a mission. It was—and is—a

mind-set particularly enabling the brutal expediency that is an enduring aspect

of war.

In commenting on Kurt Meyer’s trial and death sentence, a

Canadian general asserted he did not know of a single general or colonel on the

Allied side who had not said “this time we don’t want any prisoners.” In fact,

there is a generally understood distinction, fine but significant, between not

taking prisoners and killing them once they have surrendered. Recent general-audience

works on the Canadians and Australians in World War I, for example, are

remarkably open in acknowledging relatively frequent orders at battalion and

company levels of “no prisoners” before an attack. Shooting or bayoneting

unarmed men is another matter entirely. It might be called the difference

between war and meanness.

James Weingartner highlights the discrepancy between the US

Army’s judging of war crimes by Americans and its response to comparable

offenses involving Germans. That was not a simple double standard. For the

Americans, as for the British and Canadians, expedience and necessity remained

situational rather than normative, on the margin of legal and moral systems but

not beyond them. On the German side of the line, hardness transmuted expediency

into a norm and redefined it as a virtue. Impersonalization and

depersonalization went hand in hand. Interfering civilians or inconvenient POWs

might not be condignly and routinely disposed of—but they could be, with fewer

and fewer questions asked externally or internally. The French government was

shocked and embarrassed to find Alsatians represented among the perpetrators of

Oradour. Defended in their home province as “forced volunteers,” they were

tried and convicted, but pardoned by Charles de Gaulle in 1953 for the sake of

national unity.

The inability of the Waffen SS to break through on the north

shoulder removed any possibility of success Watch on the Rhine might have had.

Instead of exploiting victory, Das Reich and Hohenstaufen found themselves

stymied by roads blocked for miles by abandoned vehicles out of fuel or broken

down. While the SS ran in place, however, Manteuffel had used his infantry

skillfully to infiltrate, surround, and capture most of the green 106th

Infantry Division’s two forward regiments before sending his armor forward. The

116th Panzer made for Houffalize. Second Panzer and Panzer Lehr pushed through

and over the 28th Infantry Division toward Bastogne, destroying an American

armored combat command in the process.

The 101st Airborne Division got there first, dug in, and has

been celebrated in story, if not song, ever since. The Germans originally hoped

to take the town by a coup de main. When that proved impossible, Bayerlein

argued that Bastogne was too important as a transportation center to be

bypassed. Manteuffel was already concerned that his forward elements were too

weak to sustain their progress; attacking Bastogne in force would only make

that situation worse. He was also too old a panzer hand to risk tanks in a

house-to-house fight against good troops. The Panzer Baron had begun his career

in the horse cavalry, understood the importance of time for Watch on the Rhine,

and decided to mask the town and continue his drive toward the Meuse.

That the choice had to be made highlighted the growing

difficulty the panzers faced in being all things in every situation. In 1940,

motorized divisions had been available for this kind of secondary collateral

mission. In 1941, the marching infantry could be counted on to come up in time

to free the panzers for their next spring forward. In 1944, 15th Panzer

Grenadier Division did not arrive at Bastogne from army group reserve until

December 24.

Fifth Panzer Army benefited from a cold front that set in on

the night of December 22, freezing the ground enough for the Panthers to move

cross-country. Soft ground, however, was the least of Manteuffel’s problems.

His spearheads knifed 60 miles deep into the American positions, along a

30-mile front. Second Panzer Division, generally regarded by the Americans as

the best they faced, got to within five miles of the Meuse on December

24—ironically near Dinant, where 7th Panzer had staged its epic crossing in

1940. But its fuel was almost exhausted. Model responded by ordering the

division to advance on foot. Brigadier General Meinrad von Lauchert had been

commanding the division only since December 13. He had been a panzer officer

since 1935, led everything from a company to a regiment in combat, and

recognized bombast. But he was not a sorcerer, and could not conjure fuel where

none existed. Second Panzer was at the far end of its operational tether.

By platoons and companies, Americans fought bitter defensive

actions throughout the sector—in one case holding out in a castle. Thirty-two

men would be awarded the Medal of Honor from first to last during the Battle of

the Bulge, and determination increased as word spread that the Germans were not

taking prisoners. To the north, what remained of the 106th, a regiment of the

28th, and combat commands of 7th and 9th Armored Divisions, held another key

road junction—St. Vith—for five vital days against first infantry, then the

elite panzers of the Führer Escort Brigade from Model’s reserve. Not until 2nd

SS Panzer Division advanced far enough to threaten the town from the north did

the hard-hammered garrison withdraw.

In the process of working their way forward, elements of

Dietrich’s panzers seeking to evade the clogged roads in their sector began

edging onto 5th Panzer Army’s supply routes. Manteuffel ordered them kept off;

the corps commander responded by establishing roadblocks whose men were

authorized to use force to regulate traffic. There are no records of shots

being fired, but army and SS columns remained entangled as tempers flared and

cooperation eroded.

Model released some of his characteristic nervous energy by

briefly directing traffic himself, while reassuring Hitler that the chances of

victory remained great. But the overall supply situation was rapidly deteriorating.

The clearing skies accompanying the cold front meant the return of allied

planes en masse: an average of 3,000 sorties a day, disrupting operations and

turning the movement of troops and vehicles to nighttime—including the vital

fuel trucks.

Model had from the beginning recommended eschewing a drive

to the Meuse in favor of a quick turn north to isolate and then encircle the

dozen or so American divisions concentrated around Aachen. Dietrich’s staff had

been clandestinely working on a similar backup plan since December 8.

Manteuffel underwrote their thinking on December 24, when he phoned the High

Command and declared Antwerp was beyond his reach.

Any lingering optimism was dispelled on Christmas when 2nd

Panzer was attacked by its literal counterpart, the 2nd US Armored Division.

The Americans encircled the panzers’ leading battle group, destroying it as

artillery and RAF Typhoons frustrated relief efforts by the rest of the

division supported by elements of the 9th Panzer, newly arrived from High Command

reserve. Six hundred men escaped—walking and carrying no more than their

personal weapons. It was getting to be a habit for the panzers. Two thousand

more were dead or prisoners. Over 80 AFVs remained on the field, knocked out or

with empty fuel tanks. The rest of the division fought on around the village of

Humain, so fiercely that it took one of the new flame-throwing Shermans to burn

out the last die-hards. On December 27, 2nd Panzer was withdrawn. On January 1,

1945, it reported exactly five serviceable tanks.

Panzer Lehr, on 2nd Panzer’s left, had moved more slowly and

less effectively—due in part perhaps to a bit of self-inflicted fog and

friction. Bayerlein missed a possible chance to reach the Meuse when, on

December 22, he halted to rest his men and allow them to celebrate Christmas

with the extra rations sent forward for the occasion. According to some

reliable accounts, Panzer Lehr’s commander had also sacrificed a good part of

December 19 flirting with a “young, blond, and beautiful” nurse in a captured

American hospital.

The story invites comparison with the “yellow rose of

Texas,” whose dalliance with Santa Anna allegedly distracted the Mexican

general in the crucial hours before the battle of San Jacinto. But a harem of

nurses would have made no difference as Allied reinforcements continued to

arrive in the northern sector and Patton’s Third Army conducted a remarkable

90-degree turn north that took it into Bastogne on December 26.

Hitler was confronted with two choices: evacuate the salient

and withdraw the panzers for future employment, or continue fighting to keep

the Allies pinned down and draw them away from the industrial centers of the

Ruhr and the Saar. Being Hitler, he decided on both. The infantry was left to

hold the line, supported by what remained of the army’s panzers and,

temporarily, the Waffen SS, for whom Hitler had other plans.

The operational result was two weeks of head-down fighting

as American tanks and infantry hammered into the same kind of farm- and-village

strong points that had so hampered Watch on the Rhine. Now it was German

antitank guns ambushing Shermans whose relatively narrow treads restricted

their off-road mobility in the deepening snow. Not until January 16 did

Patton’s 11th Armored Division connect at Houffalize with elements of the 1st

Army advancing from the north, forcing back Panzer Lehr despite its orders to

hold the town “at all costs.” For the next two weeks the Americans pushed

eastward as the defense eroded under constant artillery fire and air strikes.

It was not elegant but it was effective. The Bulge from first to last cost the

Germans over 700 AFVs—almost half of the number committed. About half the

Panthers still in German hands were downlined for repair.