Mussolini’s first appearance on an international stage was

at Lausanne at a conference summoned in late 1922 to settle Turkey’s borders

after the fall of the Ottoman Empire. His fellow delegates were not impressed

by Italy’s new prime minister. The British foreign secretary, Lord Curzon,

found him ‘a very stagey sort of person’ who was always trying to create an

effect, sometimes with a band playing ‘Giovinezza’ in attendance. On the

opening day of the conference Mussolini contributed nothing to the discussions

and spent his time strutting around with his blackshirts and making eleven

statements to the press. Although he left Lausanne the following day, still

without any achievement, Italian newspapers managed to describe his performance

as their country’s first diplomatic success since 1860.

Mussolini’s directives to his delegation soon convinced

Curzon that, apart from being ‘stagey’, the fascist leader was a ‘thoroughly

unscrupulous and dangerous demagogue, plausible in manner, but without scruple

in truth or conduct’. From Rome he threatened almost daily ruptures of the

alliance with the Great War victors and warned he would withdraw from the

conference unless he was promised a slice of the Middle East, a stance that

suggested to Curzon ‘a combination of the sturdy beggar and the ferocious bandit’.

Soon he went beyond threats and adopted a policy that the South African prime

minister, Jan Smuts, described as ‘running about biting everybody’. When four

Italians working for an international boundary commission were mysteriously

killed on Greek soil, Mussolini delivered an impossible ultimatum to Athens and

then bombarded and occupied the island of Corfu, killing a number of civilians.

Although the Italians were eventually persuaded to evacuate, they did so only

after the Greek government was made to pay a large indemnity for a crime it

knew nothing about and which was probably committed by Albanians. The Duce was

determined, like the Venetians of old, to control the Adriatic and demonstrate

the fact.

Mussolini was converted to imperialism in his thirties at a

time when the idea of empire was losing ground in other parts of the world. The

Atlantic empires of Spain and Portugal had long gone, and Britain and France

were faced with increasing opposition in some of their colonies. The British

may have been building a new imperial capital in Delhi, but by now much of the

subcontinent’s administration was being conducted – except at the very top – by

Indians. Yet when Mussolini embraced an idea, he invariably hugged it to

excess. He talked about reviving the Roman Empire and incorporating within it

Malta, the Balkans, parts of France, parts of the Middle East and most of north

Africa. Although he had signed the Treaty of Locarno in 1925, which was

intended to guarantee peace in western Europe, he later raved about defeating

France and Britain by himself, of marching ‘to the ocean’ and acquiring an

outlet on the Atlantic. Like Crispi, he wanted colonies for reasons of prestige

rather than for their wealth – such as it was – or their potential as a place to

settle land-hungry Italians.

Fascist Italy inherited certain colonial positions which it

quickly resolved to strengthen. Somaliland thus had to be properly subdued and

ruled more vigorously than before. The situation was more complicated in Libya

because the liberal regime, aware that by the end of the Great War it

controlled only a few areas along the coast, had made an agreement with the

Senussi leader which gave the Arab tribes autonomy and economic assistance in

exchange for accepting Italy’s sovereignty. This created a very unfascist state

of affairs, and the policy was soon abandoned in favour of subjugating the

tribes, first in Tripolitania and later in Cyrenaica. In 1930 two senior

generals, Pietro Badoglio and Rodolfo Graziani, herded the entire population of

Cyrenaica into detention camps where conditions were so bad that thousands of

people perished along with nearly all their goats and camels. The following

year the ‘rebel’ leader in Cyrenaica, the septuagenarian Omar al-Mukhtar, was

captured and executed in front of his followers. Half a century on, when a film

called the The Lion of the Desert was made about this heroic figure, it was

banned in Italy on the grounds that it was ‘damaging to the honour of the

Italian army’.

Mussolini believed that a nation could only remain healthy

if it fought a war in every generation. The Italian army had been fighting for

years in Libya, but its activities there did not count as a war: it was

carrying out the ‘pacification’ of a territory that already belonged to Italy.

The real thing would be to conquer and annex a foreign country. Mussolini was

old enough to remember the defeat at Adowa and he had long-nurtured ideas of

avenging it by conquering Ethiopia and overthrowing its emperor, Haile

Selassie. It was unfortunate that the country was Christian, independent and a

member of the League of Nations, but the Duce was not deterred by such things.

He had generally disliked and affected to despise the League, a body formed in

1920 from which his new admirer, Adolf Hitler, had already withdrawn; he also

had some support from the French foreign minister, Pierre Laval, who had

allegedly offered him ‘a free hand’ in Ethiopia.

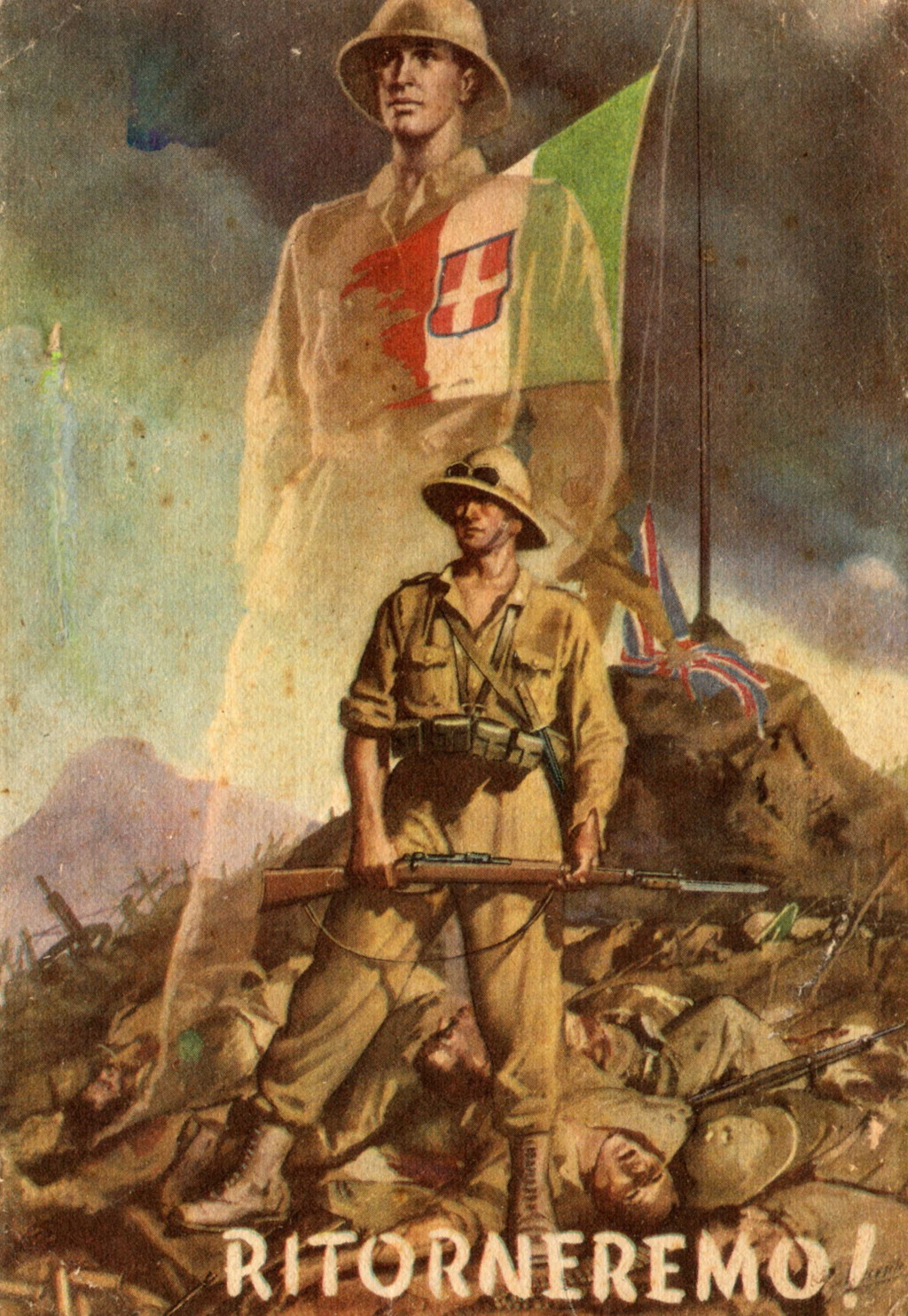

Mussolini had assembled a huge force of 400,000 men,

consisting of regular troops and fascist militiamen, and in October 1935 he

ordered them to invade Ethiopia from Eritrea and Somaliland. Although he knew

the invasion was initially unpopular at home, he believed that a rapid victory

and the consequent prestige of imperial ownership would change public opinion.

After a triumphant entry into Addis Ababa, fascism would be unstoppable; it

would next turn against Egypt, throw the British out and liberate Italy from

the ‘servitude of the Suez Canal’. Seven months after the campaign’s inception,

Badoglio’s troops entered the Ethiopian capital, an event which earned their

commander the title of Duke of Addis Ababa. Victory justified the prediction of

the Duce, who informed ecstatic crowds at home that, after a gap of fifteen

centuries, empire had returned to the seven hills of Rome. Gentile seemed to

embody the national mood when he claimed that Mussolini had not only founded an

empire but ‘done something more. He ha[d] created a new Italy.’ One ludicrous

aspect of the enterprise was the military boastfulness that followed. The

victory may have been Italy’s first ever without allied support but it was

hardly, as its propagandists claimed, one of the most brilliant campaigns in

world history: you did not have to be brilliant in the 1930s to defeat an enemy

that possessed neither artillery nor an air force.

Victory was achieved with the help of poison gas and bombing

raids on civilian targets. One of Mussolini’s sons wrote a book about his

experiences as an air force pilot in Ethiopia, describing fighting as ‘the most

beautiful and complete of all sports’ and recalling how ‘diverting’ it was to

watch groups of tribesmen ‘burst out like a rose after [he] had landed a bomb

in the middle of them’. The sport did not cease after the proclamation of

victory. As in Libya in the decade before fascism, most of Ethiopia remained

unoccupied by Italian troops, and native resistance continued after the fall of

the capital. Mussolini reacted by ordering a systematic policy of terror,

burning hundreds of villages, executing prisoners without trial and shooting

all adult males in places where resistance was discovered. When weapons were

found in the great monastery of Debra Libanos, at least 400 monks and deacons

were murdered; the Coptic Archbishop Petros, who had come from Egypt to be head

of the Ethiopian Church, was also executed. When in February 1937 two Eritreans

threw grenades at the viceroy, Marshal Graziani, killing seven people and

wounding others (including the viceroy), the local fascist boss gave his men

three days to go on the rampage, ‘to destroy and kill and do what you want to

the Ethiopians’. At least 3,000 Africans – and probably many more – were

slaughtered in consequence. The victims had nothing to do with the bomb

throwers; they did not even belong to the same part of the fascist empire.

Italian soldiers used to enjoy the reputation of being brava

gente, good fellows, ‘the good soldier Gino’ who remained good even in uniform.

Italians claimed they were not like the Nazis. Nor were their generals, whose

decency is supposed to have been certified later by the fact that none of them

faced a trial like the leading Nazis at Nuremberg. Yet in recent decades an

Italian historian, Angelo del Boca, has gone through the colonial records and

painstakingly compiled, in volume after volume, evidence that the generals

committed horrific atrocities in Africa and later the Balkans and that ‘the

good soldier Gino’ is a myth: the brava gente were as adept at massacring as

anyone else. The Italian army reacted by trying to have Del Boca prosecuted for

‘vilifying the Italian soldier’.

In July 1936, two months after the capture of Addis Ababa,

Mussolini decided to fight another war, this time in support of Franco’s

insurrection against the republican government in Spain. He dispatched a

squadron of bombers, which he soon added to, and a small army of blackshirts,

which he increased with regular soldiers so that ultimately Italy sent 73,000

Voluntary Troops to the Iberian Peninsula. Fascists and their apologists

claimed they were sent to counter the ‘Bolshevik threat’, but at that moment no

such threat existed. The Spanish Communist Party had sixteen deputies in a

Cortes of 473, it was not part of the government, and communism was not even

mentioned in the manifesto that Franco issued to justify his rebellion.

Communism only became a force in Spain because the government, opposed by Italy

and Germany and ignored by Britain and France, had to appeal to the Soviet

Union for arms.

Mussolini decided to intervene in Spain because he believed

intervention would add to the glory of Italy and its Duce. This time he was

wrong. Fighting Spanish republicans backed by Russian tanks was very different

from fighting African tribesmen, and it was demoralizing to be facing fellow

Italians in the International Brigades who kept the volunteers awake at night

with loudspeakers urging them to show solidarity with the workers by deserting

to the Spanish government’s side. At the Battle of Guadalajara in March 1937,

Mussolini’s troops were blocked by republican units that included the Italians

of the Garibaldi Battalion, and they were forced to retreat, losing a lot of

men, arms and prestige in the process. Although it was a clear defeat for the

fascists, the Duce managed to proclaim it a victory.

Historians have long been divided between those who believe

that Mussolini intended all along to build an empire and an alliance with

Germany and those who see the Duce as more of a predatory opportunist than a

dedicated expansionist and aggressor. The sheer erraticism of the man, his

frequent doubts and changes of mind, make one wonder whether he could really

have been as single-minded as the ‘intentionists’ believe. He had the eye of a

chancer, looking for easy pickings such as Corfu and later Albania, which he

invaded a week after the end of the Spanish Civil War. He admired the German

Reich much more than the French Republic yet, when in 1934 Austrian Nazis

murdered his ally Chancellor Dollfuss in Vienna, he signed a treaty with France

and talked about war against Germany. Mussolini was a show-off who thought in

slogans which he seldom wholly believed in – he did not, for example, really

think it better to live one day as a lion than 100 years as a sheep. And he was

always talking about fighting wars even when he had no intention of waging one.

His neutrality in 1939, his dithering in 1940, his failure to produce a

half-decent army and his refusal to join the war until France was beaten – none

of this suggests the character of a conqueror.

Yet it is easy to build up a case on the other side, and

certainly there is space for a compromise. Even before the rise of the Nazis,

Mussolini had hoped for an alliance with a revived Germany and a joint war

against France and Yugoslavia; he also believed that ‘the axis of European

history passes through Berlin’. In 1932 he ordered Italian newspapers to

support the Nazis in elections that brought them to power, and in the same year

he sacked his foreign minister for allegedly being too fond of the French and

the British. Although Mussolini held ambivalent views about Hitler and liked to

belittle him, he supported most of the Führer’s actions in the years before the

Second World War. He accepted the German army’s occupation of the Rhineland,

like Hitler he fought for Franco, and he eventually acquiesced in Germany’s

annexation of Austria in 1938 and its occupation of Czechoslovakia the

following year. Renzo De Felice, the author of a seven-volume biography of the

Duce, used to argue that fascism was very different from Nazism, that Mussolini

desired to be a mediator in Europe, and it was only Britain’s championing of

economic sanctions against Italy after its invasion of Ethiopia that drove

Mussolini into the German camp. Yet this sounds too much like the plea of the

apologist. Had he wished, Mussolini could have preserved peace and contained

Hitler by aligning himself with Britain and France. He chose instead to join

Germany, securing the support of a powerful ally to protect his position in

Europe while he pursued his dream of empire in Africa.

On a state visit to Germany in 1937 Mussolini was hugely

impressed by the sight of armament factories and army parades staged in his

honour. Soon afterwards he took Italy out of the League of Nations, made

anti-Semitism a fascist policy and signed an anti-communist pact with Germany

and Japan. In March 1938 he was perplexed (and privately furious) that Hitler

grabbed Austria without warning him, and later in the year he made his sole

appearance as a mediator, going to the Munich conference to persuade the Führer

to opt for the peaceful cession of the Sudetenland rather than a military

invasion of Czechoslovakia. Yet Mussolini felt uncomfortable in the role of

peacemaker, as he soon demonstrated when he told the fascist Grand Council that

Italy must acquire Nice, Corsica, Albania and Tunisia.

At Munich the Duce was deeply unimpressed by the British

prime minister (Neville Chamberlain) and the French premier (Édouard Daladier),

whose feeble performances in the face of Hitler’s pugnacity reinforced his view

that Britain and France were decadent and geriatric states that could easily be

defeated by the young and virile nations of Germany and Italy. Much influenced

by a meeting of the Oxford Union in 1933, when idealistic undergraduates had

voted against fighting ‘for king and country’, Mussolini had decided that the

British were effete and unhealthy (and too fond of umbrellas), that their

empire was in terminal decline, and that their country should be destroyed like

Carthage. He also convinced himself that Italy could capture Egypt without

difficulty because the British were unable to fight in the heat; perhaps he was

unaware that they had won a few summer battles over the years in India. Such

views were strengthened by reports from his ambassador to London, Dino Grandi,

who watched British soldiers on parade and dismissed them as ‘marionettes of

wood’ who would be too cowardly to defend their country.

In March 1939 Germany enacted another aggression without

warning Italy, this time overturning Mussolini’s ‘success’ at Munich by seizing

Prague and setting up a German ‘protectorate’ in Bohemia and Moravia. Although

the Duce felt humiliated by this episode, he decided to stand by ‘the Axis’ and

to demonstrate parity with Germany by conquering something for himself. After

briefly considering Croatia as a target, he opted for Albania, a strange

decision considering that the little country was already largely under Italian

control. In May Germany and Italy formalized the Axis with the ‘Pact of Steel’,

a name that, while professing equivalence between the two signatories, drew

attention to the disparity in industrial might: Germany produced ten times as

much steel as Italy. Once again the Germans were dishonest with their ally.

They told Mussolini that no European war would take place for over three years,

which would give him time to strengthen his armed forces and to hold his big

exhibition, the EUR in Rome. They also pretended they had no intention of

attacking Poland, although Hitler had already selected September 1939 as the

month for his invasion and on the day after the pact’s signature he informed

his generals of his plans. When Mussolini finally learned that the Germans were

about to strike, he panicked and sent Ciano, his foreign minister, to entreat

them to desist. Although keen to fight and make territorial gains – what he

called ‘our share of the plunder’ – he was beginning to have doubts about

Italy’s armed forces and how they might perform in battle.

Among his other posts, the Duce was minister for the army,

the navy and the air force, and he talked so much about the invincibility of

each service that Italians were led to believe they were as good as any in

Europe. He boasted that he could raise an army of 8 million men – a figure he later

raised to 12 million – yet he was unable to produce rifles for more than a

sixth of that number; he vaunted Italy’s technological skills, though some of

his best artillery had been captured from the Austrians in the Great War; and

he claimed to possess enormous tanks, though the Italian model was little more

than an armoured car, and its vision was so limited that it had to be guided by

infantry walking ahead, often with fatal results for the guides. No wonder

Farinacci told Mussolini he was the commander of ‘a toy army’ or that, after

inspecting it, the German war minister in 1937 had concluded that his country

would stand a better chance in the coming war if Italy was on the other side.

A great deal of money was spent on speedy new battleships,

but these were ineffective in action, and their guns apparently failed to hit a

single enemy ship at any time during the war; far more dangerous were the

courageous Italian frogmen and the manned ‘slow speed torpedoes’ (known as

maiali – pigs) entering the harbours of Gibraltar and Alexandria and inflicting

considerable damage on British ships. More sensible than building battleships

would have been the construction of aircraft carriers, which would have been

useful for attacking Malta, a strategic goal that Mussolini ignored until it

was too late; they might also have protected the rest of the fleet from

devastating raids by the RAF. The greatest deficiencies, however, were in the

air force, which the Duce had taken charge of in 1933, when he sensed that

Balbo was doing too well in the job – a replacement that proved disastrous for

Italy. Mussolini claimed to have over 8,500 aeroplanes, so many that they could

‘blot out the sun’ and so effective they could reach London or destroy

Britain’s Mediterranean fleet in a single day. Yet in fact he had fewer than a

tenth of that number, and he failed during the war to build a great many more.

At the height of the conflict Italy was manufacturing as many aeroplanes a year

as the United States was producing in a week. One of the most revealing

statistics about the inefficiency of fascism is that Italy managed to produce

more aeroplanes in the First World War than it did in the Second.

While Mussolini vacillated during the August of 1939, news

of the Ribbentrop–Molotov pact made some fascist leaders question the wisdom of

an alliance with Germany; communism was after all meant to be their chief

enemy. At a meeting of the Grand Council earlier in the year, Balbo had

criticized the policy of ‘licking Hitler’s boots’ and later he suggested that

Italy should fight on the side of Britain and France. This suggestion had no

appeal to Mussolini. Although in September he declared Italy’s neutrality or

‘non-belligerence’, his sympathies had been long with the Nazis, and he wanted

to fight with them when he was ready. Meanwhile he played for time by demanding

from the Germans more millions of tons of oil, steel and coal than they could

possibly supply and transport. All the same, he knew that a position of

neutrality was rather ridiculous for a man who had been threatening wars for

seventeen years and who was still telling Italians that warfare was ‘the normal

condition of peoples and the logical aim of any dictatorship’. At the beginning

of 1940 he warned his government that Italy could not remain permanently

neutral and ordered the armed forces to be prepared for war against anyone,

even Germany. Soon afterwards he issued bizarre instructions to the navy, which

in the coming war was to go on the offensive everywhere, to the air force, which

was to remain passive, and to the army, which was to stay on the defensive in

all places except east Africa, where it would attack the British colonies. Even

more bizarrely, he continued to erect costly fortifications along the Alpine

frontier with Austria, a policy he did not abandon during the war and which

understandably annoyed the Germans, who had already demonstrated in the case of

the Maginot Line that such defensive schemes were outmoded and useless.

The Nazis’ rapid conquests of Denmark and Norway in April

1940 convinced some waverers that Germany would win the war. Yet Mussolini

continued to hesitate until France was close to collapse in June. Believing

that Italy would somehow gain prestige as well as territory by defeating an

already defeated enemy, he then announced a ‘lightning war’ against France and

Britain to a crowd in Rome which, as leading fascists admitted, showed little

enthusiasm for the enterprise. Many Italians were undoubtedly embarrassed about

joining a war after Paris had fallen and the British army had scuttled back

across the Channel. Yet a large majority did not want to fight anyway: even

Victor Emanuel later claimed he was against the war although, as in May 1915

and October 1922, he did not try very hard to make the right decision.

On 17 June the French asked Germany for an armistice, and

three days later Mussolini ordered an attack on them. An Italian army was

dispatched to the Alps, where it suffered many casualties and failed to defeat

a far smaller French force that suffered hardly any. Once France was out of the

war, the Duce made territorial demands in Europe, Africa and the Middle East,

but the Germans told him to curb his appetite until Britain had also been

defeated. In the meantime they suggested he used his huge army in Libya to

attack the British in Egypt and capture the Suez Canal. Yet Mussolini was now

more interested in conquest close to home and, instead of attacking an enemy

power in Africa, he wanted to invade a neutral country in Europe, Greece. In

October 1940 a large Italian army duly assembled in Albania and invaded Greece,

where it was stopped by numerically inferior opponents and forced to retreat.

By then the Duce had at last ordered an attack on Egypt, but the results were

even more disastrous. Graziani’s army of over 250,000 men was defeated in a

series of engagements by 36,000 British troops, and 135,000 prisoners were

taken. The Italians fared no better at sea: after defeats by the British at

Taranto in November 1940 and at Cape Matapan the following spring, the navy

remained in harbour and played little further part in the war.

Hitler had made an offer of German tanks for Italy’s

Egyptian campaign, which Mussolini had rejected because he wanted his troops to

win glory on their own. As a result, the Führer had to send an army under Field

Marshal Rommel to defeat the British in north Africa and regain the initiative.

The Italians also had to be rescued in Greece, which the Germans quickly

overran in an operation that delayed their invasion of Russia and thus

contributed to their later defeats on the Eastern Front. This series of

military failures reduced Italy to a very subordinate role in the Axis. It had

already lost Addis Ababa and Italian Somaliland, and the main task of its

armies was now to garrison the Balkans while the Germans and later the Japanese

did most of the fighting. The behaviour of their forces in south-eastern Europe

rivalled the savagery of their allies and buried the myth of ‘the good soldier

Gino’. After provoking guerrilla warfare from partisan groups in Yugoslavia,

Italian troops carried out extensive reprisals against civilians. In the

province of Ljubljana alone, a thousand hostages were shot, 8,000 other

Slovenes were killed, and 35,000 people were deported to concentration camps.

In July 1943 Anglo-American forces invaded Sicily, landed a

few weeks later on the Italian mainland and spent the next twenty months

slogging their way north through the Apennines against a German defence

brilliantly conducted without air support. Soon after the landings in Sicily,

the Grand Council in the presence of Mussolini approved a motion to return

military command to Victor Emanuel, a move that led to the dismissal of the

Duce and his eventual imprisonment at a skiing resort in the Apennines. He was

replaced as prime minister by the vain and elderly Marshal Badoglio, a

disastrous choice. Together with the king, this former chief of staff dithered

for six weeks, remaining in the Axis, until the imminence of the Allied

landings at Salerno forced them to accept Anglo-American terms for an

armistice. They continued to dither even after that, failing to do anything to

prevent German reinforcements from rushing south to occupy the peninsula as far

down as Naples. Although they had promised to help the Anglo-American forces,

the two changed their minds and even cancelled an Allied attack on Rome, which

Badoglio himself had requested, on the very day it was planned to take place.

Fearful for their personal safety, premier and sovereign fled across the peninsula

to Pescara and, accompanied by hundreds of courtiers and generals, took ship to

Brindisi, far from the threat of the Germans. It was a very thorough abdication

of responsibility. Badoglio did not even inform his fellow ministers he was

leaving and gave no orders to his troops except to tell them not to attack the

Germans. Left on their own in increasingly chaotic circumstances, Italian

forces offered little resistance to the Germans in Italy or the Balkans, and

nearly a million of them were quickly captured; on the island of Cephalonia,

where Italians did resist, 6,000 soldiers and prisoners of war were murdered by

the Nazis. In mid-October, from the safety of Apulia, Victor Emanuel declared

war on Germany, a move that gained Italy the status of ‘co-belligerent’, eased

the country’s post-war relations with the victors and enabled hundreds of men

to avoid trials for war crimes.

The collapse of the state made it easier for the Germans to rescue Mussolini from his mountain prison and install him as their puppet ruler of the Republic of Salò, a new fascist state based on Lake Garda in the Nazi-held north. Many young men volunteered to fight for this new entity, which intellectuals such as Gentile, Papini and Marinetti were also prepared to support. Mussolini himself returned to the beliefs of his youth, insisting once more that fascism was a revolutionary ideology and that industry should be nationalized. Yet he was too demoralized and too powerless to do much except whine about the defects of his countrymen. The chief significance of Salò was that it encouraged the growth of the Resistance, the Italian partisans, and within a short time led to a civil war in the north marked by terrible atrocities, most of them committed by the republic’s ‘black brigades’.

Even in his impotence Mussolini deluded himself with the

thought that he was a great man, comparable to Napoleon, and that he had been

brought down by the character of the Italians. Even Michelangelo, he had

earlier pointed out, had ‘needed marble to make his statues. If he had had

nothing else except clay, he would simply have been a potter.’ At Salò

Mussolini grumbled that he had tried to turn a sheep into a lion and had

failed; the beast was still ‘a bleating sheep’. Yet he himself did not die like

the lion he had pretended to be: in April 1945 he ran away to the north,

disguised as a German, with wads of cash in his pockets. Captured by communist

partisans on the western shore of Lake Como, his final moment may have been

slightly more impressive. According to one report, he opened the collar of his

coat and told his executioner to aim for the heart.

The flight of Badoglio and Victor Emanuel marks one of the

lowest points in the history of united Italy. The nation dissolved: all real

power was now in the hands of the Germans, the British and the Americans. Italy

might be built anew, but it could never be the same Italy.

Both Italians and foreigners have liked to think of fascism

as an aberration, as an unlucky and almost accidental episode in the history of

a constitutional country. Sforza regarded ‘the vain show of the fascist years’

as ‘only a brief interlude of unreality’, while Croce described the

dictatorship as a ‘parenthesis’ in his nation’s story, implying that it was not

closely connected with what happened before or after. The genuine connection,

so it was claimed, was between the regimes that preceded and succeeded

Mussolini. The young liberal Piero Gobetti may have got closer to the truth

when he observed in the 1920s that fascism was part of Italy’s ‘autobiography’,

a logical consequence of unification’s failure to be a moral revolution

supported by the mass of the people. That fascism was ‘the child of the

Risorgimento’ was also Gentile’s verdict, a view much derided in the years to

come but supported intrinsically at the time by the fact that so many liberal

fathers had fascist sons without having family ruptures.

Fascists liked to present themselves as a continuation of

the Risorgimento but at the same time as a breach with its liberal heirs. The

exercise was never very convincing because, apart from the abolition of

parliamentary elections, the fascist ‘revolution’ changed little of substance,

certainly in comparison with the French Revolution of 1789 or the Spanish

Revolution of 1931. It retained the monarchy, protected private property,

exalted the family and established good relations with the Church. Abroad its

policies were aggressive and avaricious but not so very different retained the

monarchy, protected private property, exalted the family and established good

relations with the Church. Abroad its policies were aggressive and avaricious

but not so very different from those of some preceding governments. Both Crispi

and the earlier Victor Emanuel had wanted war in Europe and colonies outside,

and they and many others had spoken in tones almost as bellicose as those of

Mussolini.

The real break in Italy’s twentieth-century history came not

in 1922 but at the end of the Second World War. The essence of Risorgimento

thinking, which had been liberal, nationalist and anti-clerical, evaporated

after 1945 and was replaced by the anti-nationalist ideologies of communism and

Christian democracy. At the same time Italy abandoned its pretensions to become

a Great Power and concentrated, with far more success, on achieving prosperity

for its citizens.