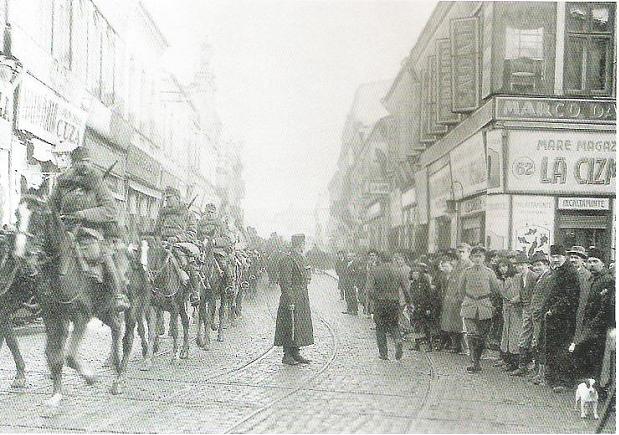

Falkenhayn and his staff of the German 9th Army during the Romanian Campaign, World War One, 1916. There are Hungarian hussars on the picture.

At the end of August 1916, Romania declared war on

Austria-Hungary, and shortly afterwards found herself at war with all four

Central Powers. Since 1914, men had been waiting for this. Romania awaited

national unification, and coveted the tracts of Austria-Hungary inhabited by

Romanians. So long as the Central Powers appeared invincible, Romania could not

risk intervening against them. Her strategic situation was peculiarly

vulnerable. But with the great run of Russian victories, her confidence rose.

Moreover, by August 1916, the western Powers were prepared to guarantee much

more territory than hitherto: the French, in particular, with an eye to the

post-war situation, wanted to establish a greater Romania as a bulwark against

Russia. On 17th August, a military convention was signed, providing for

extensive Entente assistance, financial and military. The twenty or so Romanian

divisions would, it was thought, decisively affect the eastern front as a

whole. With 366 battalions of infantry, 106 squadrons of cavalry and 1,300 guns

(half of them modern) the Romanian army could invade Hungary and turn the

Central Powers’ lines to the north.

It is not altogether easy to see why men expected the

intervention of small powers to be so decisive. No doubt it was an illusion

that—like much else in this war—owed something to misreadings of Napoleonic

history. The nationalistic vibrations of Madrid and Lisbon were thought to have

shaken the French Empire at its foundations; the Peninsular War to have exposed

the ‘soft underbelly’ of Napoleonic Europe. In reality, nationalism had been

much less important than the heavy pounding to which the French armies had been

subjected in Austria and Russia; and men also forgot that the Peninsular War

involved an army that was, by the standards of the time, large and efficient.

The Romanian army could not stand comparison. Of its 620,000 soldiers, a third

would be taken up in supply-lines, and almost all were illiterate. The officers

lacked experience, and were also inclined to panic. All foreigners noted the

incidence of what was delicately known as ‘immoralité : indeed among the first

prescriptions,, on mobilisation, was a decree that only officers above the rank

of major had the right to use make-up. Langlois, not an unfriendly observer,

thought the ‘soldat excellent, officier dépourvu de toute moralité militaire,

Etat-major et commandement presque nuls’ . British observers felt that the

operations of the Romanian army would make a public-school field-day look like

the execution of the Schlieffen Plan; while the comments of Russians who had to

fight side-by-side with the Romanians were often unprintable. As things turned

out, it was the Russians, and not the Central Powers, who suffered from a

Romanian ulcer. Almost a third of the Russian army had to be diverted to the

south. This did not save Romania. On the contrary, the Central Powers conquered

the country easily enough, and, in the next year and a half, removed far more

from it than they could have done had it remained neutral: over a million tons

of oil, over two million tons of grain, 200,000 tons of timber, 100,000 head of

cattle, 200,000 goats and pigs, over and above the quantities requisitioned for

maintenance of the armies of occupation. Romanian intervention, in other words,

made possible the Germans’ continuation of the war into 1918.

The essential reason for this, as for the halting, overall,

of Russian victories, was the Central Powers’ capacity to shift their reserves

quickly. In Napoleonic days, sea-power had allowed the British to shift their

troops faster than the French, who were dependent on horses. Now, railways gave

much the same advantage over sea-power that sea-power had had before over

horses. Provided the railways were properly-managed, they could shuttle troops within

a few days from Italy to Volhynia, France to the Balkans. It had taken the

Germans, in spring 1915, hardly more than a week to assemble their XI Army

against the Russian lines at Gorlice, whereas it took the western Powers six

weeks to assemble an equivalent force for their assault on the Dardanelles at

the same time; and even the Turkish railways were such that the western Powers

had to face a superiority to two-to-one within a few days of their landing at

Gallipoli. In September 1916, the Central Powers sent 1,500 trains through

Hungary—not far short of the number used by Austria-Hungary to mobilise against

Russia two years before—and assembled a force equivalent to the entire Romanian

army within three weeks of Romania’s intervention. In the First World War, it

was the great profusion of reserves that counted for most. Contrary to legend,

it was not so much the difficulty, or physical impossibility, of breaking

through trench-lines that led to the war’s being such a protracted and bloody

affair, but rather the fact that even a badly-defeated army could rely on

reserves, moving in by railway. The conscription of whole generations, and

particularly the enlarged capacity to supply millions of soldiers, meant that

man-power was, to all intents and purposes, inexhaustible: even the total

casualties of this war were a small proportion of the available man-power.

The basis of Brusilov’s great successes in June and July

1916 had been the Central Powers’ inadequate use of their reserves. To some

degree, this was a consequence of Brusilov’s own methods: a broad-front,

well-prepared, many-front offensive between Volhynia and Romania. Local

reserves had been frittered away between the various points of attack. In the

southern sector, on both sides of the river Dniester, the Central Powers had

been particularly embarrassed by Brusilov’s methods. They left troops to cover

the Romanian border, as well as troops to cover the Dniester flank of Südarmee,

on which their Galician lines depended. Seven Austro-Hungarian divisions, and

even a German force, the Karpatenkorps, had been pushed in to defend the

Hungarian border and the southern Bukovina: a force contained, as things turned

out, by little more than a Russian cavalry corps. The Russians had been able to

win further great victories along the Dniester, which had forced a further

diversion of German and Austro-Hungarian reserves and thus allowed the Russians

in Volhynia to win successes in July. It was of course true that the Russian

army, by following Brusilov’s methods, itself dispensed with reserves that

might have followed up the victories it won. But the prizes were great enough:

by the end of August, the Austro-Hungarian army had lost 614,000 men in the

east, and the Germans, by their own account, 150,000.

More important, however, had been the confusion among the

Central Powers’ leaders. Ludendorff would not help Falkenhayn, and Falkenhayn

would not help Conrad, since each one had his priorities, of which even

military disaster produced merely a re-statement. Falkenhayn’s priorities had

been in the west: Verdun, then the Somme, preliminary bombardment for which had

begun on 24th June. He resented any diversion of troops from France, and

demanded that Conrad should give up his Italian offensive first. Conrad was

reluctant to do this, because that offensive seemed to promise real success. In

this way, only five divisions were sent from the west for most of June, and

initially only two and a half from Italy. The divisions were also tired from

fighting—in the case of the German divisions, tired from Verdun to the point of

virtual uselessness in the field, as the fate of Marwitz’s offensive on the

Stokhod showed. At the same time, both Conrad and Falkenhayn appealed to

Ludendorff, commanding the greater part of the Germans’ eastern front. But

Ludendorff also made out that he could not afford to part with troops, and in

June sent only two under-strength divisions to help in Volhynia. He had good

excuses. His troops faced twice their numbers, and although Kuropatkin and

Evert seldom bothered to attack with any seriousness, the threat was always

there. In any case, none of the men in Ludendorff’s headquartersfelt any

sympathy with Falkenhayn. Hoffmann thought that ‘the Austrians’ defeat is no

doubt deplorable, but that is no reason for us to tear our hair out’. On the

contrary, since Falkenhayn had reduced Ludendorff’s sphere of responsibility,

the business must be settled by him and Conrad. Maybe, too, Ludendorff secretly

calculated that withholding reserves would so embarrass Falkenhayn and Conrad

that they would have to let Ludendorff once more control most of the eastern

front. Whatever the case, throughout June 1916 the Austro-Hungarian front

acquired only a dozen reserve divisions, at that frittered away between the

Dniester and the Stokhod. This had allowed Brusilov to win a further set of

victories in July.

However, these conditions were not to be repeated. In the

first place, the realisation—as distinct from the threat—of allied offensives

allowed troops to be made free from the other fronts on a scale that few people

had imagined possible. In the west, the Anglo-French offensive on the Somme was

effectively contained by half the numbers of men and a third the number of guns

that the attacking armies used. Similarly, the Russian offensive at

Baranovitchi turned out to be a bungled, ineffective affair that cost the

attacker 100,000 men for nothing in particular. On the Italian front, a renewed

Isonzo offensive, though leading to the fall of Gorizia in August, did not

prevent departure of another four Austro-Hungarian divisions for Russia in

July, and more than that later on.

In any case, the divisions among the Central Powers’ leaders

were overcome by establishment of an increasingly united command, dominated by

Ludendorff. This was the outcome of a crisis inside Germany and Austria-Hungary

that owed its existence to much more than military factors. Discontent inside

Germany had been building up throughout 1916. Emergence of a large-scale

left-wing opposition to the war—the creation of a dissident socialist group,

the strikes of spring 1916—prompted demands for a military dictatorship that

would at once win the war and control the working-class. The run-down, relative

and absolute, of the comfortable middle-class world had now progressed so far,

as inflation bit into ‘fixed incomes’, as to drive a large section of

propertied Germany to desperate courses, in which the existing, relatively

moderate leadership of men like Bethmann Hollweg and Falkenhayn had little

place. There were demands for unlimited war-aims, for use of any and every

weapon, however barbaric, that could win the war: hence the widespread campaign

for resumption of unrestricted U- Boat warfare, the sinking of any ship neutral

or not, within the ‘war-zone’ of British and French waters.

Characteristically, this situation drove Bethmann Hollweg

and Falkenhayn further apart than ever, as each sought to sacrifice the other

for his political life. Falkenhayn tried to pin the blame on Bethmann Hollweg,

and picked up the cause of submarine-warfare. Bethmann Hollweg knew in his

heart that this weapon would fail. It would provoke the United States into

declaring war, and that would be the end of Germany. At the same time, the

desperate temper of propertied Germany was now such that a demagogic campaign

for U-Boat warfare could sweep Bethmann Hollweg away. He had to try for

something equally popular, and hit on the scheme for putting Hindenburg and

Ludendorff back in charge of the eastern front. These two men enjoyed a vast, and

not wholly deserved, reputation: they were the men who produced

newspaper-headlines, and public opinion resented the whittling-down of their

power in 1915. By championing them, Bethmann Hollweg could pose as nationalist

demagogue. At the same time, he appears to have had secret schemes. He knew,

now, that Germany had little chance of winning the war. But to obtain peace,

with the atmosphere as it was, would be impossible. It was not just that the

Entente’s demands would be impossibly high; it was also that a large and

powerful section of German public opinion demanded crushing victory, and

resented any whisper to the effect that Germany’s gains could be renounced for

the sake of a compromise-settlement. Bethmann Hollweg seems to have supposed

that, by putting Ludendorff in Falkenhayn’s place, he could satisfy the

nationalists; then he could smuggle peace in through the back door. In this

roundabout way, Bethmann Hollweg came to support the ostensibly ‘jusqu’

au-boutiste’ generals, but for the sake of his private limited goals. The tone

was altogether that ascribed to Low to Baldwin: ‘If I hadn’t told you I

wouldn’t bring you here, you wouldn’t have come.’

Falkenhayn’s position really depended on his having the

Kaiser’s confidence, and the confidence of military leaders whom the Kaiser

respected. His victories in 1915 had strengthened his position; but defeat at

Verdun, and the embarrassments of the summer of 1916, much weakened his hold on

power. Above all, the eastern front showed that Falkenhayn’ methods had failed.

His relations with the Austro-Hungarian high command were so bad that, in the

decisive days of the Dniester collapse, not a single communication between

Falkenhayn and Conrad von Hötzendorf was made for several days. Relations with

Ludendorff were such that Ludendorff, with forty-four infantry divisions, would

do nothing to help: he sent a few battalions in June, and two divisions early

in July. The Verdun campaign had to be abandoned. It also became clear that

matters in the east would not be settled until Ludendorff somehow got

sufficient responsibility to make him part with reserves for the front south of

the Pripyat: and from Falkenhayn’s viewpoint, the difficulty was to combine

extension of Ludendorff’s responsibility with containment of Ludendorff’s

power.

One obvious way was for Falkenhayn to promote schemes by

which the whole of the eastern front—including the Austro-Hungarian army—would

come under Hindenburg’s command, and then to stir up opposition from the

Austro-Hungarians. This method was tried early in July. Ostensibly, it

succeeded. Conrad von Hötzendorf produced a litany of grievances against the

scheme: German command in the east would make the war one of ‘Germandom against

Slavdom’, and would therefore offend the Slavs who made up half of the

Austro-Hungarian army; German command would mean that the Habsburg dream of

reigning in Poland would be rudely destroyed; it would prevent free movement of

troops against the hated Italians; it would prevent a separate peace. Instead,

schemes were promoted by which Archduke Friedrich, nominal commander of the

Austro-Hungarian army, should nominally take over the whole of the eastern

front, with Hindenburg as his chief of staff for the German part. This did not

meet an enthusiastic response from Hindenburg. Falkenhayn seemed to have

parried the threat: he had ostensibly promoted Hindenburg’s cause, and the

Austro-Hungarians had turned out to be the obstacle. But his calculation went

wrong. With the disasters of mid-July, indignation in Berlin, Vienna and

Budapest rose beyond Falkenhayn’s barriers. Highly-placed

Austro-Hungarians—including Andrássy—demanded establishment of a

Hindenburg-front; Bethmann Hollweg also demanded it, as did the Kaiser. In the

end, Austro-Hungarian resistance gave way. By the end of the month, after a

meeting in Pless, a new system of command was adopted, by which Hindenburg ran

the eastern front virtually as far as the Dniester. In theory, he accepted

orders, as far as the Austro-Hungarian sector was concerned, from Conrad. In

practice, this was as meaningless as it had been in the days of Mackensen. The

only area still commanded by Conrad was the front of Archduke Karl’s Army

Group, on the southern sector of the front; even it had a German chief of

staff, Seekt; and an increasing proportion of its troops was German. Later on,

the system was extended to take into account other allies. When Romania

intervened, the German Kaiser became commander-in-chief of all of the Central

Powers’ forces, a device to prevent the Bulgarians from making separate

arrangements. At the same time, Falkenhayn was finally dismissed, and replaced

by Hindenburg, whose place as Oberbefehlshaber Ost passed to Prince Leopold of

Bavaria.

In this way, central control of reserves became increasingly

possible, and in August there was little of the confusion that had marked June

and July. In June, a dozen divisions, mostly tired, had been sent; but by

mid-August the eastern front had received a transfusion equivalent to the

entire Austro-Hungarian Galician army of 1914: thirty infantry and three and a

half cavalry divisions, of which ten infantry and almost all of the cavalry

divisions came from Ludendorff’s front once Ludendorff was made responsible.

This transfusion matched what Brusilov was sent: three divisions to mid-June,

fifteen more to mid-July, eight more to mid-August. When the Romanians

intervened, the Central Powers’ system for pooling reserves worked equally

well: the Romanian offensive was stopped in its tracks a mere fortnight after

the declaration of war, as all four Central Powers mustered substantial forces

against Romania almost at once.

At the same time, the Russians now abandoned the Brusilov

method that had brought such remarkable results: they returned to the old

system of attacking a narrow front in a predictable way with a huge phalanx. In

the first half of July, repetition of Brusilov’s methods had brought, again,

great successes. The Central Powers’ salient on the Styr had collapsed; there

had been great advances along the Dniester; and even the German Südarmee had

been forced back in Galicia. But the Brusilov method could succeed, in the

first place, only if new troops were constantly fed to the front. But this

would depend on the generosity of the other two army group commanders, who effectively

controlled the reserves. As usual, the only way of achieving this turned out to

be appointing them to command the offensive. Consequently, Evert was now put in

charge of the northern part of Brusilov’s front, and was given responsibility

for the offensive of III Army, the Guard Army and VIII Army against the Central

Powers’ positions before Kowel. With this, the Brusilov offensive came to an

end, since Evert had no faith in Brusilov’s methods. On the contrary, he, with

Alexeyev’s blessing, returned to the ‘phalanx’ system: a vast attack on a very

narrow front, with so much artillery mustered that nothing living would remain

on the enemy side. III Army deployed eighty-six battalions against sixteen, and

was to attack on only eight kilometres; the Guard Army deployed ninety-six

battalions against twenty-eight and attacked on a front of fourteen kilometres.

Stavka could either renew the Kowel offensive or,

particularly after Romania’s intervention, attempt some repetition of the

Brusilov successes by attacking virtually everywhere along the line, if need be

diverting substantial Russian forces towards the new Romanian front. In

practice, Alexeyev opted for the renewal of the Kowel offensive, and continued

to place most of the reserve troops with the three armies engaged in this.

Later, when that offensive produced huge casualties for no significant return,

and when Romania collapsed, this decision was made out to be criminal. It did,

certainly, betray much want of imagination. On the other hand, from Stavka’s

point of view, it seemed to make sense. The British and French were attacking

on the Somme, and Russia must also mount some powerful offensive at a point

where the Germans could not afford retreat. A proper offensive would also

prevent the Germans from shifting troops against Romania. It was true that the

Brusilov methods—a many-front offensive, with long fronts of attack at each of

the points—had succeeded in June and July. But they needed extensive

preparation, for which there was no time; and in any case the fact that they

had succeeded against Austro-Hungarian soldiers damned them in professional

soldiers’ eyes, for the Austro-Hungarian army was now thought to have reached

such a state that it could be beaten by an army commanded by a rocking-horse:

victories won against Austro-Hungarians proved nothing. Now that the Germans

had arrived, something serious must be tried. The ‘phalanx’ levelled at Kowel

was the only answer to this problem, or so Stavka supposed.

There was a further justification for renewal of the Kowel

offensives, which gave them a prima facie case of unfortunate strength. In the

offensive of late July, there had been respectable tactical successes. The two

Guard Corps had lost heavily towards the end of July, but in doing so they had

captured over fifty guns and some enemy bridgeheads on the Stokhod. If the

troops could get over the Stokhod marshes into easier country beyond, then they

might turn such tactical successes into a strategic victory—the more so as the

Central Powers’ defence still depended to some degree on the soldiery of the

Austro-Hungarian IV Army which, as Hoffmann said, resembled ‘a mouthful of

hyper-sensitive teeth: every time the wind blows, there’s tooth-ache.9 In the

fighting of late July, almost a whole Austro-Hungarian division had been

captured—12,000 men—with only two guns: a sign that the forces were simply not

fighting. Hell, Linsingen’s chief of staff, regarded the whole thing as ‘a

powder-barrel’; and Marwitz himself thought that the Russians’ weight was now

such that battles before Kowel ‘resemble conditions in the west’. Alexeyev

opted for renewed attacks on Kowel, and neglected the chance of winning victory

further south. To some degree, he even managed this with Brusilov’s consent.

Offensives against Kowel were mounted on 8th August and at

more or less fortnightly intervals for the next three months. The Russian superiority,

overall, was two-to-one at least: north of the Pripyat, 852,000 to 371,000 and

south of it, 863,000 to 480,000. On the Kowel front, a great local superiority

was built up: III Army, the Guard Army and VIII Army had, together, twenty-nine

infantry and twelve cavalry divisions to twelve Austro-German infantry

divisions. This, rather than the Romanian front, constituted Stavka’s main effort.

It was a complete failure. Heavy artillery would be concentrated on a narrow

front. But the shell was not particularly effective, since marshy country

masked the explosion. The attacking troops had to stumble across marshy

country, pitted with shell-holes, and found in the Stokhod marshes an

impassable obstacle. Moreover, the tactics used were much like the strategy

itself: theoretically the obvious answer, in practice calamitous. Troops

advanced in ‘waves’, one after another, and were therefore very vulnerable to

heavy rifle-fire, traversing machine-guns, high-explosive shell. The Guard—and

especially the Semenovski and Preobrazhenski regiments—attacked seventeen

times, with wild courage, and made none but trivial gains, So many Russian

corpses lay stinking in no-man’s land that Marwitz, the German commander, was

approached with a view to establishing a truce, so that they might be buried.

He refused: there could be no better deterrent to future offensives than this

forest of rotting corpses. But for Stavka, these tactics seemed to be the

obvious answer. It was easy enough for men simply to walk forward from a

trench, in a long line; and troops that followed them into the trench would

walk forward similarly. Again, a long, thin target was seemingly less

vulnerable to artillery-fire than the thick masses which had been the rule for

attackers in 1914–15. But at bottom, these tactics reflected the commanders’

opinion of their men. Generals—who had found that it took ten years to make a

‘real’ soldier of the kind of volunteer they had found before the war—could not

imagine that the raw recruits of 1916 could perform any manoeuvre but the

simplest. If anything complicated were tried, the troops would break down into

a useless mob, given to panic. It was easy to have the troops walk forward in a

long line, dressing to the left, their officers in front and their

sergeant-majors behind, ready to shoot any man who left his place. Commanders

therefore neglected tactical innovations—in particular, the principle of fire-and-movement,

by which small ‘packets’ of infantrymen, moving forward in bounds, diagonally,

from shell-hole to shell-hole, could alternately offer each other cover. These

principles were used, first, in the German army, mainly because it suffered from

a severe crisis in man-power and had to think of some way by which lives could

be saved. Other armies, with a longer ‘purse’, were saved the effort of

thinking things out, or of applying doctrines the truth of which they

half-suspected. Yet in 1918, the allied victory owed at least as much to

tactical innovations as to improvements in weaponry, including tanks.

In these circumstances, the Kowel offensives turned into an

expensive folly. The Germans were able to re-form their weak Austro-Hungarian

partners, to the extent that the Austro-Hungarian IV Army became infiltrated,

even at battalion level, with German troops. Its Austro-Hungarian command

became a stage-prop, contemptuously shifted around by one German general after

another. The method worked. Czech and Ruthene soldiery did not respond to

Austro-Hungarian methods. But the arrival of competent German brigade-staffs, a

battery or two of German artillery, and some Prussian sergeant-majors was

generally enough to lend the Austro-Hungarian troops a fighting quality they

had not shown hitherto—‘corset-staves’, in the current phrase. In August, there

was an extension of this method to all parts of the eastern front, and on the

Kowel sector there were no more easy Russian victories. Just the same, Alexeyev

went ahead, into mid-October. When huge losses were recorded, the commanders

reacted as they had always done: there must be more heavy guns, and then

everything would be all right. Evert, indeed, learnt so little from Kowel that

for 1917 he demanded sixty-seven infantry divisions for a further offensive,

with ‘814,364’ rounds of heavy shell, to be used on a front of eighteen

kilometres. As ever, when the old formulae failed, generals did not suppose

that this was because the formulae were wrong, but because they had not been

adequately applied. In the end, Russian soldiers were driven into attack by

their own artillery: bombarding the front trenches in which they cowered.

The successes won by the Russian army in August were on

parts of the front still subjected to the Brusilov method. XI, VII and IX

Armies in eastern Galicia and the Bukovina ‘walked forward’, as before. XI and

IX Armies in particular did this to great effect. Brody fell, and Halicz, in

the south, as the multiple offensive on a broad front disrupted Austro-German

reserves. It was the victories of IX Army that finally prompted Romania to

intervene, since Lechitski’s drive almost brought the Russians into Hungary,

and hence into occupation of lands coveted by the Romanians. Yet because so

many Russian troops were now involved in the Kowel battles, there was almost

nothing to back Lechitsky, whose victories were achieved with a mere eleven

divisions of infantry (and five of cavalry). By the end of August, his drive

had slackened, while the incurable tendency of Shcherbachev and Golovin, of VII

Army, to apply French methods meant that Brusilov’s prescriptions were ignored,

and the attacks against Südarmee turned into a minor version of Kowel.