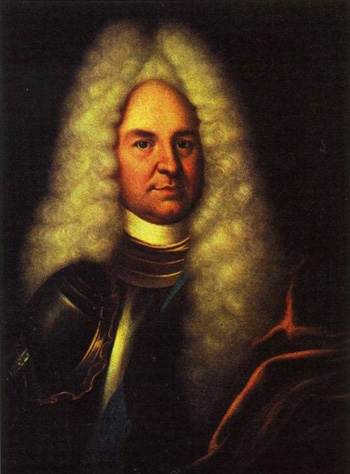

Patrick Leopold Gordon

Patrick Gordon fathered three sons and two daughters. Of the

lads, the eldest succeeded to the lands of Auchleuchries but the other two

followed their father’s path into the Russian army. His eldest daughter,

Katherine, married a German officer but was widowed in 1692 when her husband

lost his life in an accident with fireworks. In 1700 she married again, this

time to a kinsman of her father, Alexander Gordon. The latter came to Russia in

1696 after a spell in the French army, no doubt enticed by the success and

status of Patrick, and stayed on to rise to the rank of major-general.

After securing his position on the throne of Russia, Peter

the Great embarked on a drive to make his backward nation a powerful and

significant force in Europe. At the start of his reign Russia’s only direct

access to the open sea was through the cold, distant port of Archangel, and the

temptation for Peter was to establish outlets on the Black Sea and the Baltic.

It was an ambition, however, that brought him into conflict with the Ottoman

Empire and Sweden. In 1697 Karl XII had succeeded to the throne of the Vasas

and almost at once had to contend with troublesome neighbours: as well as

Russia, Poland and Denmark were itching to recover lost territories. In 1698,

all three formed an alliance to combat Sweden. Karl got his blow in first,

capturing Copenhagen in 1700 and forcing a surrender on Denmark, before

switching his attention to the east, defeating the Russians at Narva and Riga,

and occupying Courland. In 1701 the Swedes moved into Poland and then on into

Saxony. Karl, however, was stretching his resources dangerously thin, and it

could only be a matter of time before he would meet a reverse. It came at the

siege of the fortress of Poltava in Ukraine in July 1710: in the battle the

Swedes lost almost 16,000 men as casualties or prisoners and, although Karl

himself escaped with a handful of followers, it marked the end of Sweden’s

dominance of the Baltic. Among the prisoners taken by the Swedes at Narva was

Alexander Gordon. Back in Russian service, he defeated his former captors at

Kysmark and went on to defeat the Poles at Podkamian. He died at Auchintoul in

1751.

The Gordons – Patrick and Alexander – stand out as examples of Scots in the service of Peter the Great, but there were several more of their kinsmen and their countrymen in prominent military positions. For example, take George Ogilvy. A grandson of James Ogilvy of Airlie and son of an Ogilvy who became governor of Spielberg in Moravia, George was born in 1648 and rose to the rank of major-general in the service of the Habsburgs before Peter the Great spotted him in Vienna in 1698 and invited him to join the Russian army. His work in training and modernising Peter’s forces brought him to the rank of field marshal. He later switched to the service of Poland and died in Danzig in October 1710. Then there were the brothers James and Robert Bruce, whose father, William, had been a colonel in Russian service. James followed an interest in the natural sciences, including chemistry, and Tsar Peter put him in command of artillery. He also apparently showed a talent for shady financial dealing but this did not prevent him playing an important role in the Peace of Nystadt in 1721 when Russia finally acquired Estonia, Livonia and the lands around the head of the Gulf of Finland from Sweden. James was rewarded with an estate, where he died in 1735; he was buried in the Simonoff Monastery in Moscow. His titles were inherited by his nephew Alexander, who also achieved the rank of major-general and fought against the Turks.

John Graham of Claverhouse, later Viscount Dundee

Among the many Scots who distinguished themselves under the

different flags of Europe it is worth noting a few who are remembered for

exploits on their home soil but who had their first taste of armed conflict

abroad. John Graham of Claverhouse, Bonnie Dundee himself, travelled to France

after he graduated from St Andrews in 1668 to be a volunteer in the service of

Louis XIV. He moved four years later to the Low Countries to a commission as a

cornet in one of the Prince of Orange’s troops of horse guards. His arrival

coincided with the outbreak of war between the Netherlands and France, when

William of Orange was able to form an alliance with, among others, the

Habsburgs. On 11 August 1674, a joint Spanish–Dutch force under William’s

command was attacked by a strong French army at Seneffe near Mons and forced

into retreat. During the desperate confusion, William might have been captured

when his horse foundered in a marsh had not John Graham dismounted to give his

commander his saddle, an act for which he was promoted to captain. Perhaps

Graham presumed too much on the prince’s good will for he was passed over when

he later applied for promotion to lieutenant-colonel of one of the Scots

regiments in Dutch service and was aggrieved enough to quit the Low Countries,

returning to Scotland at the end of 1676.