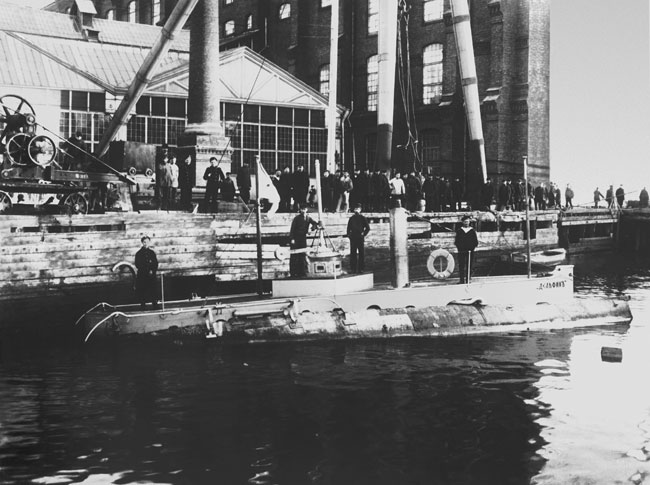

The DELFIN was a product of the Bubnov committee at the tum of the century and was considered by many as the first true combat submarine in the Russian Navy. Following the outbreak of the Russo-Japanese War in 1904 the DELFIN was employed as a training ship in the St. Petersburg area for officers and men assigned to new construction submarines.

Russian submarine Kasatka.

British journalist Fred T. Jane, writing in 1899 after an

extensive tour of naval installations in Russia, observed, “I may,

however, mention that the Russians believe very much in underwater craft, and do

not regard the submarine battleship as an idle dream.”

This statement, although an exaggeration of the situation in

Russia at the time, was indicative of the high degree of interest in submarines

among Russian naval authorities at the beginning of the 20th century. The

modern Russian submarine fleet in many respects dates from the establishment,

on 19 December 1900, of a special submarine committee of the Naval Technical

Committee (MTK-Morskoy Technicheskiy Komitet). Its purpose was to evaluate

foreign submarine designs and prepare proposals for one that could be

constructed for the Russian Navy. The chairman of the submarine committee was

the noted engineer Ivan Grigor’evich Bubnov, who would be responsible for most

Russian submarine designs until the collapse of the tsarist government in 1917.

The other committee members were Lieutenant Mikhail Nikolaevich Beklemishev, a

graduate of the Naval Academy in the constructor branch, and mechanical

engineer Ivan Semenovich Goryunov. The committee studied projects submitted to

the 1898 competition held in Paris, and proposals by the Russian submarine pioneer

Dzhevetskiy and the Frenchman Maxime Laubeuf. In 1901 Beklemishev visited the

United States, where he became acquainted with the submarine designs of John P.

Holland and Simon Lake. He also visited Great Britain, France, and Italy to

look at contemporary submarine efforts in those countries.

While the Bubnov committee did its work, Russia’s first

submarine of the 20th century was constructed in 1901 at Kronshtadt to the

design of engineer Nikolai Nikolaevich Kuteinikov and Lieutenant (later

Captain) Evgeniy Viktorovich Kolbas’yev. Their submarine was intended to be

carried on deck of surface warships and to be launched when within attack range

of enemy ships.

This submersible displaced 20 tons, was 50 feet (15.25 m)

long, and had a beam of about 4 feet (1.2 m). Propulsion was provided by

electric motors driving six propulsors (screws) with power supplied by six Bary

accumulators, which were evenly divided be- tween three forward and three after

compartments, as were the ballast tanks. (The hull was divided into nine

watertight compartments, a precursor to the arrangement of later undersea craft)

The interior of the boat was accessible through a hatch in the conning tower.

Both a bow and a stern rudder were fitted. The armament for this craft

consisted of two torpedoes mounted in external Dzhevetskiy drop collars. These

could be trained and fired from within the boat.

Kuteinikov was responsible for the submarine’s hull and

Kolbas’yev for the electrical installations. Upon completion in 1902 this craft

was baptized PETR KOSHKA, after a Russian sailor who had distinguished himself

during the defense of Sevastopol in the Crimean War. The craft was to be

transferred to Sevastopol for trials.

Although it was apparent that the Russian Navy was

proceeding with caution with regard to submarine construction and clearly did

not intend to invest large sums of money, a number of projects were under some

form of official consideration at the beginning of the century. One of these

was designed by Dzhevetskiy, who had lived in Paris since 1893. The design had

been reviewed at the New Admiralty yard in St. Petersburg for its practicability

in 1901, but had been discarded.

In May 1901 the Bubnov committee completed its work and

proposed to the Naval Technical Committee the development of a submarine based

on the Holland design, with some major design changes coming from Bubnov. These

changes principally consisted of situating the main ballast tanks aft and

incorporating the Dzhevetskiy drop-collar launching system rather than

internally (tube) launched torpedoes. These features would be standard on most

submarine designs pre- pared in Russia up to 1915.

Detail design work on the undersea craft recommended by the

Bubnov committee began forthwith, and on 5 July 1901 the prototype boat,

ultimately named DELFIN, was ordered from the Baltic Works in St. Petersburg.

Construction proceeded under great secrecy under the direction of Bubnov and

now-Captain Beklernishev. The installation of the DELFIN’S machinery and other

equipment was completed by the spring of 1903, and sea trials began on 20 June

1903. They were evidently quite successful.

The DELFIN was considered by the Russians to have been the

first true combat submarine in their Navy. After the outbreak of the

Russo-Japanese War in 1904 the DELFIN was employed as a training ship in the

St. Petersburg area for officers and men assigned to new construction

submarines.

By mid-1903 a Dzhevetskiy submarine design of some 800 tons

appears to have been under consideration or possibly under construction, also

at the Baltic Works in St. Petersburg. There is no record that the 800-ton

Dzhevetskiy boat was completed, if indeed she was actually begun. This

particular unit was stilI listed in the 1909 edition of the German yearbook

Nauticus, although by that time it had certainly ceased to exist.

In commenting on the Russian Navy’s attitude toward

submarines at this time, the German naval attaché in St. Petersburg noted,

“Although perhaps at the moment there are only limited funds available, I

would like to bring to your attention that perhaps with the exception of some

problems still to be resolved there will be no further delays in ordering

submarines. There is a highly favorable attitude towards this new weapon in the

officer corps as well as among the engineers, reinforced by the belief that

both types are truly Russian inventions.

In this vein, encouraged by the success of the DELFIN, the

Naval Ministry on 13 August 1903 ordered the development of a design for a

larger submarine. On 20 December 1903, the Naval Technical Committee approved

the design of the KASATKA class of 140 tons prepared by the team of Bubnov and

Beklemishev. It was at the same time also agreed to construct ten sub- marines

of this design through 1914. The lead unit, named KASATKA (swallow), was

ordered from the Baltic Works on 2 January 1904, further establishing that

shipyard as the premier Russian submarine builder.

The next four units were ordered from the Baltic Works on 24

February 1904, with a sixth, funded by public subscription, ordered on 26 March

1904. These submarines were:

SKAT (ray)

NALIM (burbot)

MAKREL (mackerel)

OKUN’ (perch)

FELDMARSHAL GRAF SHEREMETEV

Thus, the first five submarines of the class were named for

fish, while the sixth remembered a Commander in Chief of Peter the Great’s

forces in victories in the Baltic area. The construction of these six

submarines was accelerated with the outbreak of the Russo-Japanese War in

February 1904, and all six units were launched between July and August 1904.

Under the pressure of war, the KASATKA was the only unit to be assembled for

trials in the Baltic. The other were prepared for transfer in sections by

railroad to the Far East.

The initial trials of the KASATKA were not very successful

and steering difficulty was noted during the first dive. This was caused by a

design fault that had placed the conning tower-and hence the center of buoyancy-too

far forward. This stability problem was temporarily solved by adding a second

conning tower aft. (Permanent new conning towers were not installed until

1906-1907.) Another defect was that the paraffin engines ordered from Germany

had not been ready in time to be installed (and in fact were never delivered).

The trouble was that these engines were to have been capable of burning either

lamp paraffin or heavy oil. The German Koerting firm was to have provided these

engines for the KASATKA as well as the subsequent KARP class. These engines

were supposed to be safer than petrol or gasoline engines. However, Koerting

had only built small, eight-horsepower engines of this type and had encountered

delays in producing the larger engines. A makeshift solution was found for the

Russian submarines by instead mounting a small dynamo for charging the storage

batteries. Another problem occurred with the KASATKA on 2 October 1904, when it

was found that a hatch was not watertight.

In general, however, the trials were sufficiently successful

that the KASATKA, SKAT, NALIM. and FELDMARSHAL GRAF SHEREMETEV were loaded for

transport by train to Vladivostok on 17 November 1904. Completion of the two

remaining submarines was delayed until 1907.

During 1905 the small experimental submarine KETA was

constructed by the engineering works of G. A. Lessner in St. Petersburg. This

was a modified and lengthened Dzhevetskiy Type III craft, designed by a

Lieutenant S. Yanovich. The craft was propelled by a gasoline engine driving

one propeller shaft, and could be armed with two torpedoes. The KETA was also

transferred to the Far East during the Russo-Japanese War. She was apparently

not successful and was stricken from the Navy list on 19 June 1908.