Almost a year would elapse before the Luftwaffe returned in

strength for the next phase of their attacks on the Midlands, this time with

Kampfgeschwader 2 (KG2) – the Holzhammer Gruppe – in the van. From April until

September/October 1942, Dornier Do217s spearheaded the notorious Baedeker air

raids against historical British towns and cities. Mounted in retaliation for

the RAF’s escalating attacks on the great cities of Germany, these raids were

stimulated in particular by those upon the Baltic ports of Lübeck and Rostock

in March and April 1942. Dornier Do217s of KG2, together with other units, were

heavily involved in the Luftwaffe plan but by the end of that summer would,

once again, suffer heavy losses to the RAF’s night defences.

Almost coinciding with the beginning of the Baedeker phase,

151 Squadron – still based at Wittering – became only the second squadron to

re-equip with the de Havilland Mosquito NF II and made its first Mosquito

patrol on April 30. The last of 151’s pilots went solo on the Mossie on June 20

and that day its diarist recorded confidently that, “the whole squadron can now

be left to its own devices”, and in common with other night fighter units, soon

got to grips with the enemy once more.

Plt Off Wain in DD608 and Flt Lt Pennington in DD628

reported some AI contacts in their patrols on the night of May 28/29 but it was

during enemy mining sorties to The Wash and anti-shipping raids in the Great

Yarmouth area on May 29/30 that the squadron’s first real engagement occurred

with the new fighter. First up from Wittering were Pilot Officer John Wain and

Flt Sgt Thomas ‘Jock’ Grieve in DD608 who tackled a Dornier 217 but could only

claim it as damaged. The same night the A Flight commander, Flt Lt Denis

Pennington and his RO Flt Sgt David Donnett in DD628, intercepted and fired at

what he thought was a Heinkel He111 out over the North Sea but spirited return

fire made him break off with an inconclusive result for him, too.

With faster fighters and more effective radar cover, the

profile of night air combat was changing distinctly, but because defending

fighters were now intercepting more enemy raiders out over the sea, it would

also become more difficult to verify some of the results of their combats and

subsequent claims.

On Wittering’s patch it was the CO of 151 Squadron, New

Zealander Wg Cdr Irving Smith, who led the way to success with the new

Mosquito. Airborne at 22.45 hours in W4097 for the first patrol of the night of

June 24/25, he and his RO Flt Lt Kerr-Sheppard were vectored by Neatishead GCI

out to sea from The Wash towards an incoming raid. At 12,000 feet altitude,

Kerr-Sheppard soon picked out a contact and guided the wing commander into

visual contact at one hundred yards range. It was a Heinkel He111 and in his

combat report, he said it looked to be carrying “two torpedoes under the

wings.” The crew of the Heinkel spotted the incoming Mosquito for it suddenly

dived vertically but not before Wg Cdr Smith put a burst of cannon fire into

the port engine, which started to blaze and the starboard torpedo – if indeed

that’s what it was – dropped away. Smith clung to the bomber, firing more short

bursts at it from his machine guns as it first dived then pulled up into a

stall turn, shedding pieces as the rounds hit home. Now the Heinkel dived again

with the Mosquito still on its tail, this time firing another burst of cannon.

Diving hard, the two aircraft were enveloped by cloud and although

Kerr-Sheppard followed it on the AI set it gradually went out of range. Smith

continued to follow the descending track of the Heinkel and at 7,000 feet

altitude Kerr-Sheppard regained a contact off to port still losing altitude but

again the target disappeared off the display. Wg Cdr Smith claimed a ‘probable’

for this one and climbed back up to look for more trade. Control put him onto

the track of another bandit and at 7,000 feet altitude in bright moonlight he

saw the aeroplane two miles distant, in fact just a few seconds before

Kerr-Sheppard called out the AI contact. Smith opened up the throttles to close

the range and then eased the Mosquito in to 300 yards behind and below another

Heinkel He111, also carrying what he also described as “a torpedo under each

wing.” He just managed to get in a one-second burst of cannon that brought hits

on the underside of the wings and fuselage before the Heinkel dived vertically.

This time, with its port wing on fire, the enemy bomber continued to dive until

it struck the water, where it left a circle of burning wreckage. Claim one

He111 destroyed.

The patrol was hotting up indeed and Wg Cdr Smith was

directed towards a third bandit on which AI contact was made but then lost at

extreme range. Circling at 7,000 feet, control put him onto a fourth bandit,

which this time was held on AI right down to visual contact at 300 yards on a

Dornier Do217. Smith fired all his remaining cannon ammunition in one long

burst at this target, spraying it with hits until wings and fuselage were

blazing and parts of the engine cowlings were seen to fall away. The Dornier

crew put up a fight, though, and fired back at their tormentor from the dorsal

guns but calmly closing the range to a hundred yards, Wg Cdr Smith silenced the

return fire with several short bursts from his own machine guns. With the

Mosquito windscreen covered in oil from the stricken bomber he was obliged to

break off the attack, but by now the Dornier was flying very slowly and losing

height rapidly. Wg Cdr Smith drew alongside the bomber and his last view of it

was as it flew into cloud, burning fiercely and eerily illuminating the cloud

from within. Out of ammunition he headed back to Wittering, landing at 00.52

hours to claim two E/A destroyed and one probable. On the question of the

torpedoes under the wings, while it is true that the Heinkel He111 could carry

such ordnance, it is possible that on this occasion – and in view of Plt Off

Wain’s combat report below – Wg Cdr Smith mistook a pair of large calibre bombs

loaded on the two bulbous hard points situated at the wing roots, for

torpedoes. The He111 had to carry bombs larger than the SC500 externally and

two SC1000 or alternatively, two parachute mines – the latter might bear some

resemblance to torpedoes when seen in poor light – and these could be what Wg

Cdr Smith saw. Furthermore, the squadron diarist didn’t do modern researchers

any favours when he logged two sorties by Mosquito W4097 at the same time on

the night of 23/24 – but flown by two different crews: Plt Off Fisher and Wg

Cdr Smith. It seems clear, though, that Wg Cdr Smith’s sortie date was flown on

that hectic night of 24/25.

Plt Off Wain and Flt Sgt Grieve left Wittering in DD616

shortly after the WingCo. They were handed over to Happisburgh CHL control

where trade was still brisk and sent off towards an inbound bandit fifty miles

out from The Wash. Wain’s combat report was equally brisk, stating:

A visual was obtained against Northern Light at one mile and

identified at 600 yards as a Heinkel 111 with two bombs stowed externally. Fire

was opened at 250 yards with cannon and machine gun. One long burst caused

starboard wing to explode and one third of the wing came off. E/A went into

vertical dive leaving a trail of smoke. Time 23.40 hours. An aircraft burning

on the sea was seen by Wg Cdr Smith, who was in the vicinity. It is claimed as

destroyed.

The night was still young and next off was Sqn Ldr Donald

Darling with Plt Off Wright (RO) in DD629 at 00.25. At 01.15 Neatishead GCI put

him onto the track of a raider heading south-east at 6,000 feet and shortly

afterwards Wright got a blip below and to starboard. Darling got a visual at

700 yards range on a Dornier Do217 but while closing to 200 yards the Mossie

was spotted and the bomber dived towards the clouds. Darling put in a short

cannon burst as the Dornier entered the cloudbank and with Wright following it

on AI he loosed off another burst as they emerged from the cloud. Return fire

came from the dorsal turret but this stopped when more bursts of cannon fire

from the Mosquito brought hits on the fuselage. Sqn Ldr Darling was unable to

stay with the Dornier as it dived hard into the cloud once more so he abandoned

the chase and climbed for more trade. After another unproductive chase Plt Off

Wright held a new contact, which they turned into a sighting of a Ju88 but once

again in the good light conditions the Mosquito was seen and this bomber, too,

dived away to sea level where contact was lost. Claim one damaged. Flt Lt Moody

flew the last, uneventful, patrol of the night.

Moody was on ops next night when the bright moonlight of

June 26/27 brought bombers from Holland in over The Wash in an effort to creep

up on Norwich from the least expected direction. A Do217E-4, wk nr 4266, of I/KG2,

was lost when Flt Lt Moody and his RO Plt Off Marsh in Mosquito NFII, DD609,

caught up with it over The Wash.

Neatishead put Moody on to what turned out to be a friendly

then directed him towards a bandit dead ahead. As Marsh was trying to pick out a

contact they got quite a fright when a stream of tracer fire zipped past them.

Moody dived out of danger and started again. GCI gave him another target at

10,000 feet altitude and Marsh got an AI blip at maximum range. The Mosquito

was easily able to overhaul the bandit and in less than a minute Moody had a

Dornier 217 in his sight at 800 yards range. He closed in from down-moon and

opened fire as the Dornier began a gentle turn to port. Hits on the fuselage

were followed by a faint glow and suddenly the bomber blew up, falling into the

sea where it exploded again. The aircraft was U5+ML flown by Fw Hans Schrödel,

who died with his crew in this engagement.

With the arrival of the Mosquito NFII the science of night

fighting had taken great strides since the days of the Blenheim just two years

earlier.

During the process of re-equipment, B Flight of 151 Squadron

soldiered on with Defiants well into that summer and the tenacity of those

Defiant crews – working mainly with the ‘eyeball Mk 1’ – had fulfilled an important

job in plugging gaps in the night defences.

Although by now usually relegated to pottering around on

searchlight cooperation sorties, it is interesting to find a few Defiants –

described by the squadron itself as “Old Faithfuls” – still around on 151

Squadron in June 1942 – for example AA425, AA436 and AA572 and on the 26th one

of these, believed to be AA572, even managed to muscle in and take a slice of

the Mossies’ action.

Flt Lt Colin Robertson with air gunner Flt Sgt Albert Beale

left Wittering at 00.56 hours on the 26th for one of the regular searchlight

cooperation sorties with sites around The Wash. They were old hands on the

Defiant and when flashes from exploding bombs and fires over in the Norwich

direction grabbed Robertson’s attention, with the turret fully armed, he could

not resist the opportunity to go and investigate. Five miles west of Coltishall

Flt Sgt Beale saw a Dornier Do217 coming up behind them at 2,000 feet altitude.

Calling for “turn port!” he brought the turret round and opened fire at the

bomber from just eighty yards range. Beale saw his fire hit the rear fuselage

and this was answered by a stream of tracer from the Dornier’s guns as it went

into a steep dive under the Defiant, where it was lost to sight.

Turning south-east Robertson saw another Dornier silhouetted

against the moon, almost stern on but turning towards them. The Defiant was

still only at 1,000 feet altitude when Beale asked for “starboard!” to close

the range to 150 yards. Opening fire, he scored hits on the nose and fuselage

and stopped return fire from the dorsal gun position. Then Beale’s guns chose

this moment to jam and the bomber escaped. Landing back at Wittering at 03.14

hours they filed a claim for two Do217s damaged and the Squadron ORB noted: “As

Defiants have not been used operationally for some time, this is likely to be

the last combat in which this type will engage.” Or so they thought.

Always keen to keep his hand in with ‘his’ squadrons,

Wittering station commander Gp Capt Basil Embry borrowed a 151 Mosquito for a

dawn patrol to try his luck at catching the ‘regular’ German PRU Ju88. Much to

his disgust he was unsuccessful and since the Luftwaffe looked like staying

away for the rest of the month, when the weather clamped in, a squadron party was

organised on the 30th to celebrate the month of June successes. But Jerry

managed to spoil Robertson and Beale’s party by sending a single raider in the

wee small hours of June 29/30.

Ground radar tracked an incoming raid across the southern

Fens and Flt Lt Robertson with Flt Sgt Beale were scrambled from RAF Wittering.

Lashed by rain and hail, their Defiant soon emerged from heavy cloud at 5,000

feet and after twenty minutes, at 03.21 hours, Robertson called “tallyho” on a

Ju88. Closing on the Junkers, it was seen flitting in and out of the cloud tops

until, when it emerged for a third time, Flt Sgt Beale let go a five-second

deflection burst of 200 AP and 200 de Wilde incendiary rounds at the bomber

from a range of one hundred down to fifty yards. Later he was of the opinion

that the enemy aircraft flew right into his gunfire but it dipped into cloud

again and did not re-emerge. The Defiant crew could only claim one Ju88 damaged

and a radio fix put them in the vicinity of the town of March in Cambridgeshire.

While much has quite rightly been written about the air war

from a pilot’s perspective, the achievement of Flt Sgt Albert Beale DFM, in

being personally credited with three enemy aircraft destroyed and four damaged

while flying in Defiants, is a fine example of the contribution made by air

gunners to the night air defence campaign.

151 Squadron continued to make successful interceptions with

its new Mosquitoes, even though Luftwaffe incursions were reducing in size and

frequency again and thus there were fewer targets to find in the same volume of

sky. Apart from the obvious factor of an individual crew’s skill in closing a

kill, that the squadron could still shoot down the enemy is the most obvious

demonstration of the complete effectiveness of the GCI/AI system – it didn’t

matter how many of them came, radar would find them.

While seeking a target of opportunity along the north

Norfolk coast on July 21/22, Ofw Heinrich Wolpers and his crew, including the

staffelkapitän Hptmn Frank from I/KG2, ran into a 151 patrol just after

midnight. Controlled by Flt Lt Ballantyne of Neatishead GCI, Plt Off G Fisher

and Flt Sgt E Godfrey in Mosquito W4090 (AI Mk V) chased the Dornier in and out

of cloud cover from The Wash to fifty miles off the Humber estuary, before

finally despatching it into the sea. The fight was not all one-sided either.

Fisher got in several bursts of cannon and machine-gun fire that eventually put

both the ventral and dorsal gunners out of action, but not before their own

fire had peppered the Mosquito under the fuselage and engine nacelles and

damaged one of the cannon spent-round chutes. Both aircraft were twisting and

turning; climbing and diving steeply from 9,000 down to 5,000 feet and back

again and it was during one of these dives towards patchy cloud cover that

Fisher fired a telling burst and the Dornier’s starboard engine caught fire.

Going down in an ever steepening dive the flaming engine was suddenly swallowed

up by the sea and Fisher who, in all the excitement had not registered his own

rapid approach to that same patch of sea, heard Godfrey yelling at him to pull

up. He pulled out of the dive at 200 feet – and went home. It had taken

twenty-five minutes of hard manoeuvring; 197 rounds of 20mm cannon and 1239

rounds of .303 machine-gun ammunition to despatch Dornier Do217E-4, U5+IH, wk

nr 4260.

One particular night in July 1942 can be seen as indicative

both of the success of the defensive night fighting force guarding The Wash

corridor, of the continuing wide-ranging radius of the sorties and of the

recurring problem of confirming combat kills in darkness, often over water.

Because of the intensity of air activity over the whole region on this night of

July 23 1942, in contrast to the usual rigid censorship and no doubt to bolster

civilian morale, the Lincolnshire Free Press newspaper was, on the occasion of

the night’s outstanding events, allowed to print an unusual amount of detail.

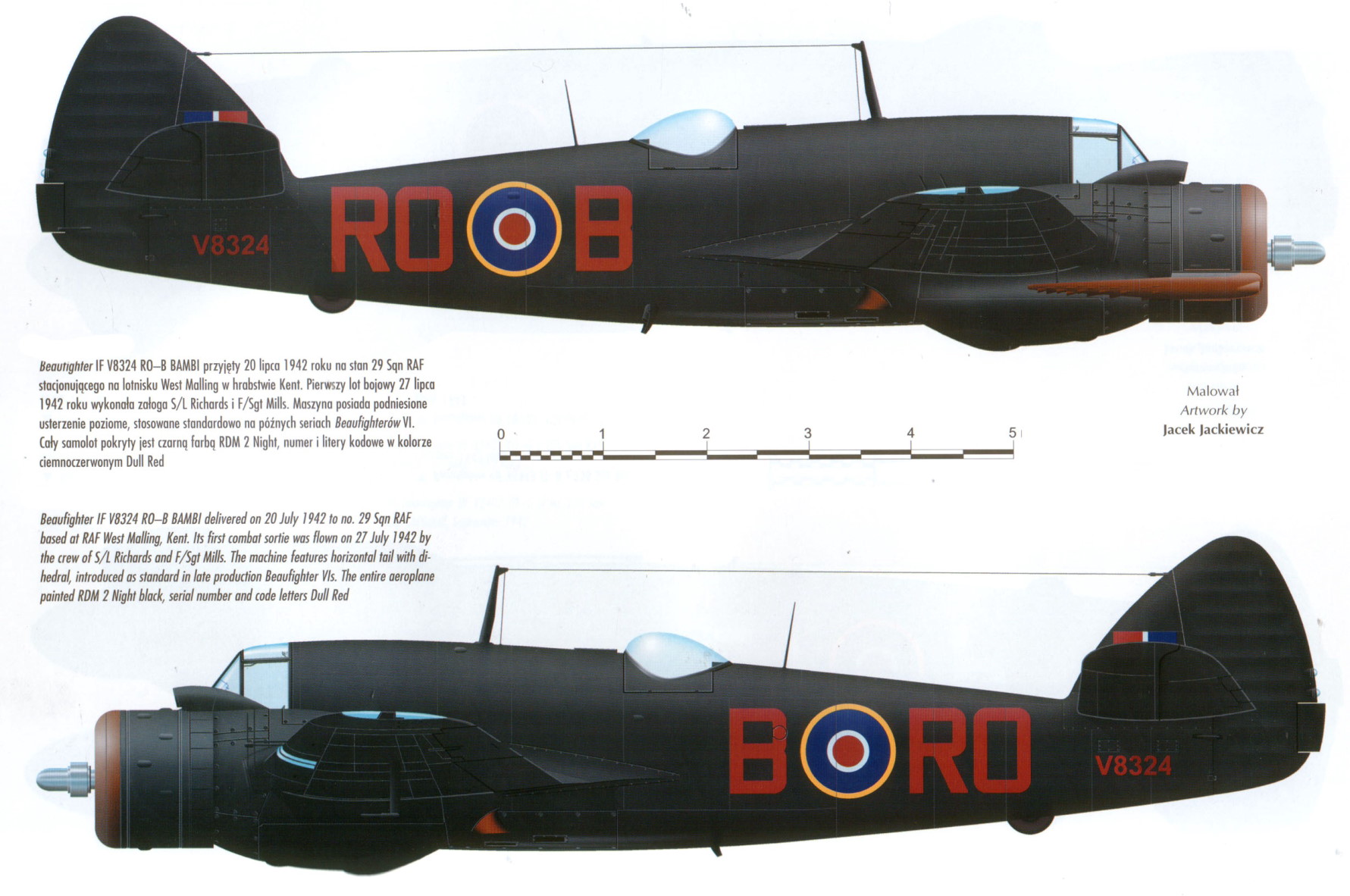

For the RAF, while – loosely speaking – Beaufighters of 68

Squadron covered the Norfolk/Suffolk region from RAF Coltishall, 151, having

recently completed its conversion from Hurricanes and Defiants to Mosquitoes at

RAF Wittering, was assigned The Wash area while the Canadians of 409 Squadron

at Coleby Grange (Lincoln), also equipped with Beaufighters, watched over the

rest of Lincolnshire towards the Humber. These then were the primary night

fighter units in the region in mid 1942. In addition, though, other squadrons

added support, so that the umbrella over the approaches to the Midlands by

night left few holes for the enemy to pass through unmolested. Not least of the

other units were the radar-equipped flying searchlight Turbinlite Havocs of

1453 and 1459 Flights (later 532 and 538 Squadrons) that flew variously from

Wittering and Hibaldstow. Until September 1942, when they were re-formed into

integrated squadrons, comprising one flight of Havocs and another of

Hurricanes, the Havoc flights drew their satellite fighters from Hurricane

units with whom they shared a base. In the case of 1453 Flight at Wittering,

when 151 re-equipped with Mosquitoes, it called upon the Hurricanes of 486 (NZ)

Squadron to make up their Havoc/Hurricane teams. However, in addition to its

Turbinlite commitment, 486 Squadron also mounted independent Fighter Night

patrols of its own. Generally speaking, though, the twin-engine fighters

patrolled about fifty miles out to sea and the singles inland from the coast

but inevitably, once the action started, it will be seen there were no rigid

areas and overlaps by all units occurred frequently.

Including the two being discussed in detail here, claims for

a total of seven enemy aircraft destroyed over East Anglia were submitted for

the night of July 23/24 1942. Five of these were made by Beaufighter crews of

Wg Cdr Max Aitken’s 68 Squadron based at RAF Coltishall, their victims

apparently falling either in the sea off the Norfolk coast or in Norfolk

itself. Wg Cdr Aitken claimed two, Sgt Truscott one and two Czech crews one

each. The other two claims were made by Flt Lt E L (Peter) McMillan of 409

Squadron and Flt Lt Harvey Sweetman of 486 Squadron. Examination of German

records in recent years, however, indicates only three enemy aircraft were lost

over England that night, while a fourth – almost certainly the result of

McMillan’s second combat – crashed on landing back at its base. Such is the

benefit of hindsight!

With the likelihood of some or all of these defending

aircraft chasing around the night sky after declining numbers of enemy

aircraft, inevitably duplicate claims were bound to happen. On this night, just

such an event occurred.

Oblt Heinrich Wiess of II/KG40 was briefed to attack an

aircraft factory in Bedford with four 500kg bombs. With his crew, Fw Karl

Gramm, Fw Hermann Frischolz and Ofw Joseph Ulrich, he took off from Soesterberg

in Dornier Do217E-4, wk nr 4279, coded F8+CN, just as the moon was beginning to

rise. His route from Soesterberg airfield in Holland took him across the North

Sea, down the length of The Wash, making landfall over Boston at 10,000 feet

before turning south towards the target. It was only five minutes after this

point that the Dornier was caught in a searchlight beam and one of the crew saw

a single-engine fighter below them about 1,000 yards away to starboard. Oblt

Wiess took evasive action by diving the Dornier, first to starboard then

curving to port to get back on course. The fighter seemed to have been shaken

off but soon another single-engine fighter was spotted below, on the port side

this time, flying on a roughly parallel course. After being interrogated later,

the transcription of flight engineer Ofw Ulrich’s recollection of events went

as follows.

He said he fired a few machine-gun rounds in its direction

and the fighter turned in to attack the Dornier from below. The first burst

from the fighter set the port wing on fire and the crew baled out. During his

parachute descent he saw a twin-engine fighter fly past but he was positive

that the aircraft at which he fired and which then shot them down was a

single-engine.

Flt Lt Harvey Sweetman, a New Zealander from Auckland,

commanded a flight of 486 (NZ) Squadron at RAF Wittering and was a founder

member of the squadron in March 1942. The Hurricane IIbs of 486 were usually

tied, at night, to the apron strings of the Turbinlite Havocs, but the results

of this technique of night interception had been singularly unimpressive so

far. On this night, however, it was Harvey’s turn to go off chasing the Hun on

his own freelance patrol and from his combat report we can piece together his

version of events.

Sweetman eased Z3029, SA-R, gently off Wittering runway at a

quarter to midnight on July 23 1942. According to his recollections after this

sortie, at first he headed north before turning on a reciprocal course that

brought him to the vicinity of Spalding. There, outlined against a cloud layer

below and to starboard of him, he spotted the menacing shape of a Dornier

Do217, flying south. As he closed in, Sweetman’s Hurricane was spotted by the

Dornier crew and its dorsal turret gunner let fly with a burst of machine-gun

fire. The bright red and white tracer rounds were way off target though.

Banking to starboard, Sweetman closed to seventy yards, loosing off a

deflection burst at the nose of the Dornier from his eight machine guns, but

without any visible effect. The Dornier dived rapidly in an effort to escape

the line of fire but Sweetman hung on down to 5,000 feet altitude, firing two

more bursts as he followed his prey. These seemed to produce an immediate

result as “twin streams of thick smoky vapour flowed from the enemy aircraft.”

Furthermore Sweetman reported that the Dornier “turned right over on its back

and dived vertically down out of sight.” Although it was bright moonlight,

there was some broken cloud around at 3,000 feet and as he orbited the spot, Sweetman

saw “the flare of an explosion below”, which he took to signal the end of his

victim. Calling up Wittering sector operations, his position was fixed to

within six miles of the crash site and he set course for base, landing back at

01.00 in an elated mood.

It was established that an enemy aircraft had crashed in a

field at Fleet Fen south of Holbeach and according to 58 Maintenance Unit (58

MU) inspectors, it was a Dornier Do217E that was entirely destroyed, with

wreckage strewn over twenty acres. It was their task to salvage as much

material as possible and gather intelligence about this latest model.

The German crew had baled out and landed in a string between

Fleet Fen and Holbeach itself and the occupants on duty in an Observer Corps

post just outside the town had quite a shock when a German airman walked in and

gave himself up! He was left in the care of two slightly bewildered observers

while a colleague, quickly picking up the only rifle in the hut, ran outside

and rounded up another of the crew a short distance away. A third German was

found hiding in a farmyard and the fourth was apprehended nonchalantly walking

down the road in his stockinged feet, having lost his boots when he abandoned

the aeroplane.

Flt Lt Sweetman duly submitted a claim for one Dornier 217

destroyed but that signalled the beginning of another battle, this time with

one of his own side. When the 486 Squadron Intelligence Officer made enquiries

to support Sweetman’s claim, the crash having been confirmed by a searchlight battery

at Whaplode Drove, he was told that a 409 Squadron Beaufighter crew, Flt Lt E L

(Peter) McMillan (pilot) and Sgt Shepherd, had submitted a claim for the same

aircraft. It was also verified that there was only one enemy aircraft shot down

in that district that night.

In an article written by Bill Norman and published in the

December 2000 issue of FlyPast magazine former night fighter pilot Peter

McMillan recalled his two particular air combats with the enemy in July 1942

and remembered how he had to share his success with another squadron. Flying

409 Squadron Beaufighter VI, X8153, it was the first of his claims that he

believed was the Fleet Fen aircraft – the one he, too, claimed as destroyed.

Peter claimed only a damaged for his second engagement. From the details

contained in McMillan’s combat report – just as with Sweetman’s – it is

impossible to reconstruct clearly his precise location at the time of the Fleet

Fen combat. However, a D/F bearing put him in the vicinity of Holbeach, and

having fired off 339 rounds of 20mm cannon ammunition, he most certainly had a

go at something that night.

McMillan’s combat report outlines his version of events. He

wrote: “Take-off from RAF Coleby Grange was at 23.05 on the 23rd and after a

short while the Beaufighter was handed over to Orby radar station to begin a

GCI exercise.” This was a quite normal procedure during a patrol so that the

night fighter crews could get in as much practice in the air as possible, at

the same time as being instantly available if ground control detected a

potential target. On this occasion, very soon GCI reported trade and McMillan

was vectored northwards. Anticipating imminent action, he told Sgt Shepherd to

set the cannon armament to ‘fire’ which involved Shepherd leaving his seat to go

forward to the central weapons bay, between himself and his pilot. While he was

doing so his intercom failed owing to a broken headset lead. Fortunately

McMillan could still hear Shepherd – vital for the interception – but Shepherd

could not hear his pilot’s responses. There was a buzzer link between the

cockpits, however, and they found by speedy improvisation of a simple code they

were able to continue with the interception.

Orby GCI put them onto a vector of 100° and warned McMillan

he would have to turn quickly onto the reciprocal of 280°. When the instruction

to turn came he brought the Beaufighter hard round and there on Shepherd’s

display tubes was the blip. But the target was jinking around and the contact

was lost just as quickly. The Orby controller gave a quick course correction

and Shepherd was back in business and this time he held on to it.

McMillan opened the throttles to 280mph at 9,000 feet

altitude and began to close in on the target. At 650 yards range he obtained a

visual to port and above and thought it to be a Dornier Do217 that was weaving

and varying altitude. Calmly McMillan slid the Beaufighter over to bring his

quarry slightly to starboard then closed to 250 yards range to make quite sure it

was a hostile.

Confirmation was soon forthcoming because at this point the

enemy opened fire, fortunately inaccurately. Slight back pressure on the yoke

brought the gunsight on and McMillan let fly with three short bursts of cannon

fire of two or three seconds each. After the third burst, a white glow appeared

on the port engine and the target began to slow down. This caused the

Beaufighter to overshoot its prey but as he passed below the Dornier McMillan

saw the port engine was on fire. He hauled the Beaufighter round in a tight

orbit and regained visual contact with the enemy aircraft silhouetted against

the moon. He was in time to see two parachutes detach themselves from the

aircraft just before it went straight down with the port engine blazing fiercely.

He wrote: “My observer saw it explode on the ground and I claim this as

destroyed.” This is a much more visually positive result than Sweetman was able

to offer.

Now 486 Squadron would have nothing to do with this

‘sharing’ rubbish and the whole squadron closed ranks to validate Sweetman’s claim.

Sweetman himself, accompanied by Sqn Ldr Clayton from Wittering operations and

Plt Off Thomas (the squadron intelligence officer), visited the crash site the

next morning where they consulted with Flt Lt Morrison of 58MU from Newark. The

latter was responsible for examination and removal of the debris. 486 Squadron

documents record that Flt Lt Morrison declared that, despite searching for

evidence of cannon strikes, he could find none. It was known of course that

Sweetman’s Hurricane was armed only with .303 machine guns. However, on this

latter point, the recollections of two former 58MU recovery team NCOs,

interviewed by Sid Finn for his book Lincolnshire Air War, provide a contrary

view as they said they worked at the site for many days and found evidence of

20mm cannon strikes on the wreckage.

The New Zealanders did not let it rest there and proceeded

to interview the police constable who had arrested the German crew. He stated

that one member of the crew said they had been shot down by a Spitfire. This

remark was taken to indicate that a single-engine, rather than a twin-engine,

aircraft was seen which lent support to Sweetman’s claim, it being easy to

confuse a Spitfire with a Hurricane in the turmoil of a night battle. In their

opinion, a final corroboration of 486’s claim came when Captain G A Peacock, a

Royal Artillery officer stationed at Wittering, made a formal written

declaration, carefully witnessed by an army colleague and Plt Off Thomas. In

his statement Capt Peacock wrote:

At about midnight I was walking in the garden of a house

at Moulton Chapel, where I was staying on leave. My attention was attracted by

the sound of machine-gun fire in the air. I saw two bursts of fire. . . after

which an aeroplane caught fire and dived steeply. It passed across the very

bright moon, making the perfect silhouette of a Dornier. The aircraft crashed,

a mile from where I stood, in a tremendous explosion… looking up again I

plainly saw a Hurricane circling and it was from this aircraft that the gunfire

originated. No other aeroplane fired its guns in the vicinity at the time of

this action.

The lengths to which 486 Squadron went to back up their

claim graphically illustrates the high degree of morale and camaraderie

existing in RAF night fighter units at this time. The outcome was that 486

Squadron believed Harvey Sweetman had proved his case conclusively, yet

ironically his original combat report does not carry the usual HQ Fighter

Command ‘claim approved or shared’ endorsement. Peter McMillan’s report on the

other hand is endorsed ‘shared 1/2 with 486 Sqdn’.

What seems clear now is that there were several enemy

aircraft and RAF fighters in close proximity that night for, in addition to the

Fleet Fen Dornier, at least one more Dornier was lost from each of KG40 and KG2

at unknown locations. The “twin streams of vapour” reported by Flt Lt Sweetman

do not necessarily mean the Dornier had been hit, since it was known that

aviation fuel had a propensity to produce black exhaust smoke when engine

throttles were suddenly rammed open. It might be felt significant that Flt Lt

Sweetman also lost sight of his target – last seen in a radical manoeuvre quite

in keeping with its design capabilities – at a critical moment, while Flt Lt

McMillan recorded that his gunfire set one engine of his target on fire and Sgt

Shepherd had it in view down to impact. On the other hand, when questioned by

486 Squadron, the MU officer – without, it has to be said, the benefit of a

lengthy inspection – is reported as saying he “found no evidence of cannon

strikes”, yet his recovery team senior NCO, who spent more than a week at the

site, firmly expressed the opposite view. Even one of the German crew admitted

seeing a twin-engine aeroplane fly past him as he fell from the bomber.

Well, in the historian’s ‘paper war’, evaluation and

accreditation may seem important – and there are certainly puzzles enough in

this incident! But in the ‘shooting war’, while there was clearly a healthy

element of unit pride involved, the only important thing in the end is that

someone actually shot down a raider when the enemy was at the gate.

This busy night was not yet over for Peter McMillan though,

and once again with the advantage of hindsight, the outcome of his second

combat was not quite as he thought.

As soon as he had reported the first kill to Orby he was

passed to sector control for position fixing and then back to Orby GCI. More

trade was reported to the east. McMillan was vectored onto 100° and advised of

a target at four miles dead ahead at 8,000 feet altitude. McMillan increased

speed to 280mph to close the gap and calmly asked Orby to bring him in on the

port side as the moon was to starboard. A stern-chase followed and when he got

within one and a half miles range of his quarry Orby GCI advised him they could

not help him any more and told him to continue on 110°. After a while Sgt

Shepherd picked out and held an AI contact although the target jinked around

before settling on a course of 090°. McMillan’s vision was hampered by cloud

now but Shepherd neatly brought him down to 1,500 yards range and there, off to

port and slightly above, was the silhouette of an aircraft. Keeping it in sight

he crossed over to approach with it slightly to starboard. With the lighter sky

behind him and fearful of being spotted, McMillan swiftly closed to 500 yards,

eased up behind it, identified it as a Dornier Do217 and let fly with his

cannons, all in a series of smooth, decisive movements. He saw flashes of his

fire hitting the enemy aircraft, which immediately did a quarter roll and dived

away. McMillan endeavoured to follow but lost sight of the Dornier and it

disappeared into the ground returns (electronic ‘noise’) on Sgt Shepherd’s

screens. When they reached 4,000 feet with 320mph on the clock he pulled out

and returned to base, claiming the Dornier as damaged.

Peter McMillan’s second adversary that night was Feldwebel

Willi Schludecker, a highly experienced bomber pilot who flew a total of 120

ops, of which thirty-two were made against English targets. Survivor of nine

crash-landings due to battle damage, Willi came closest to oblivion the night

he ran into Peter McMillan. Willi Schludecker was briefed by KG2 to attack

Bedford with a 2,000kg bomb load carried in Dornier Do217, U5+BL, wk nr 4252.

Approaching The Wash, Fw Heinrich Buhl, the flight engineer and gunner, had

trouble with one of his weapons and let off a burst of tracer into the night

sky. Willi thought that may have attracted a night fighter because a little

later the crew spotted an aircraft creeping up from astern. This is believed to

be McMillan’s Beaufighter. Displaying a considerable degree of confidence,

Willi decided to hold his course and allow it to come within his own gunners’

range. Both aircraft opened fire simultaneously with the greater muzzle flash

of the Beaufighter cannons preventing McMillan from seeing return fire and the

Dornier crew thinking their own fire had made the Beaufighter explode! When the

Dornier made its violent escape manoeuvre – bear in mind it was an aeroplane designed

and stressed for dive-bombing – they never saw each other again.

In fact Peter McMillan would have been justified in claiming

two Dorniers as destroyed that night because Schludecker’s aircraft was so

badly damaged in the encounter that he had to jettison the bomb load and head

for home. It was with the greatest of difficulty that he made it back to

Gilze-Rijen in Holland, where he crash-landed the Dornier at three times the

normal landing speed after making three attempts to get the aircraft down. That

was Willi’s ninth – and last – crash-landing because he spent the next six

months in hospital as a result of his injuries and it put an end to his

operational flying career.

On March 9 2000 Peter McMillan, Willi Schludecker and

Heinrich Buhl came face-to-face for the first time when they met in Hove at a

meeting arranged by Bill Norman. This time it was a friendly encounter between

men who, in Heinrich Buhl’s words, “had been adversaries but never enemies” and

who found they had much in common.