South Africa also feared the worst. During the white

referendum of January 1979 that preceded the April poll, Smith admitted that if

things went wrong South Africa had made ‘a very generous agreement’ to help

Rhodesian war widows and the war-wounded. (A year before South Africa had

secretly offered Rhodesian special forces, and their families, the option to

move south to join the SADF.) Pretoria was also preparing to construct refugee

camps in the northern Transvaal. And, like the British, South Africa had

considered contingency plans for the military evacuation of Rhodesians if a

wholesale carnage among whites was to take place. Against such a scenario of

fear, the whites still said ‘yes’ (85 per cent of the 71 per cent poll) to

Smith’s plan to elect the first black prime minister of Zimbabwe-Rhodesia. How

could Salisbury expect the PF guerrillas to believe that white rule was really

over and to hand in their arms, if the unborn republic was to have such an ugly

compromise name so redolent of white chicanery?

In the same month as the referendum, blacks had massively

boycotted conscription. On 10 January, only 300 out of the scheduled 1,544

blacks turned up at Llewellyn Barracks in Bulawayo. Also, 415 of the expected

1,500 whites failed to show up. Two days later whites aged 50 to 59 were told

they would have to serve for 42 days a year. Even ‘dad’s army’ would have to be

deployed for the coming general election.

On 12 February 1979, ZIPRA shot down another civilian

Viscount aircraft. Air Rhodesia Flight 827 from Kariba to Salisbury was hit by

a SAM-7. Fifty-four passengers and five crew members were killed as the plane

came down only 50 km from the spot where the first SAM victim had crashed.

Nkomo claimed that the intended target had been General Walls, who was aboard a

plane which took off just after the ill-fated Viscount. The alleged attempt to

kill Walls was probably a post-hoc rationalization: ZIPRA had intended to shoot

down a plane just before the referendum. The emotional white backlash might

have produced a ‘no’ to Smith’s plans; and this would have disrupted the

internal settlement to the benefit of the PF.

A feeling of sullen, resigned anger pervaded the white

community, which retreated further into its laager. The roads were unsafe even

for convoys; now the sky was dangerous too. Air Rhodesia flights were reduced

and old Dakotas with heat-dispersion units around the engine exhausts were

introduced on passenger runs. South African Airways cut back its flights and

stopped its Jumbo jets from landing at Salisbury airport.

On 26 February the Rhodesian Air Force launched a

retaliatory raid deep into Angola, the first major raid on that country.

Canberra jets struck at a ZIPRA base at Luso, situated on the Benguela railway

and 1,000 km from the Rhodesian border. Thanks to excellent intelligence work,

the Rhodesian pilots avoided the British-maintained air defence of Zambia and

the Russian-manned radar tracking system in Angola. In this audacious raid 160

guerrillas were killed and 530 injured. The Soviet MiG-17s at the Russo-Cuban

air base at Henrique de Carvalho (320 km to the north) did not have time to

retaliate. The guiding hand of South Africa was evident, however. The SADF was

unhappy about the SWAPO threat to South West Africa and the UN’s indifference

to guerrilla incursions from adjacent Angola. Rhodesia could act as a cat’s paw

for the SADF, and SAAF Mirages could provide some emergency protection for the

Canberras if things went wrong in Angola, despite their limited combat radius

(a factor which also inhibited the Russian MiGs). All seven Rhodesian and South

African Canberras returned safely. Ironically, on the same day as the raid

ZIPRA did shoot down a Macchi jet fighter north-west of Lusaka, but this plane

belonged to the Zambian Air Force. ZIPRA troops were jittery, as the Rhodesian

Air Force had made two big raids into Zambia in the week before the Luso

sortie. Rhodesians were in a tough mood in February; as one ComOps spokesman

discussed the cross-border strategy he said: ‘If necessary, we’ll blast them

back into the Stone Age.’

Special forces had already attacked Zambian oil depots, with

little success. On 23 March 1979, however, the SAS, with South African Recce

commando support, hit the Munhava oil depot in Beira. RENAMO was given the

credit, a frequently used device for Mozambican coastal raids. But the raiders

arrived in Mark-4 Zodiacs, courtesy of ships from the South African Navy. (The

navy also regularly supplied and transported RENAMO leaders by submarine.) The

oil depot went up in flames and the desperate Mozambicans turned to the

specialist unit of fire-fighters in Alberton, near Johannesburg. The South

Africans helped in the arson plot and then basked in the applause for their

good neighbourliness.

The Rhodesian strategy had always relied upon sound morale

and leadership. But by 1979 the prospect of black rule, even by the internal

leaders, had sapped white resilience. Grit had been transformed into mechanical

resignation. Worse was the infighting within the RF and the UANC. The senior

officers of the army were at loggerheads over military developments. An

incident in January 1979 exacerbated their strategic (and personal) schisms. On

29 January a bugging device was discovered in Lieutenant Colonel Ron

Reid-Daly’s office. As Reid-Daly was then head of the elite Selous Scouts, this

had serious security implications (though no one was actually monitoring his

calls, because the Director of Military Intelligence, Lieutenant Colonel John

Redfern, said he had actually ‘forgotten’ about it, after the Selous Scout

monitoring plan was devised in August 1978). All Selous Scouts and SAS

operations were immediately suspended. Two days later Reid-Daly launched a

personal attack on the army commander, Lieutenant General John Hickman. The

occasion was a crowded RLI mess during the drunken celebrations of the

regiment’s birthday at Cranborne Barracks. An angry Reid-Daly used more than

soldier’s language to describe his commander. Later described as being

‘overwrought and emotional’, Reid-Daly turned to Hickman, the guest of honour

and began: ‘I want to say to you Army Commander for bugging my telephone, thank

you very much.’ Raucous cheers followed. Everyone assumed Reid-Daly was joking.

Reid-Daly repeated his words, and the company went silent. Reid-Daly concluded:

‘If I ever see you again, it will be too soon.’ The two antagonists immediately

squared up for a fight, but senior officers managed to separate them. Reid-Daly

was court martialled for insubordination and given a minor punishment. He then

resigned. But the Reid-Daly/Hickman row had dredged up many murky facts about

the army. There followed a welter of accusations and counter-accusations of

gun-running and poaching. (Most prominent was the accusation that the Selous

Scouts were using the no-go areas, from which other army units were excluded,

to poach big game rather than hunt guerrillas. In some ‘frozen’ no-go areas on

the Mozambique border guerrilla bands would seek refuge in Selous

Scouts-patrolled areas and use them as a haven from patrols by other security

forces.)

After another embarrassing incident involving too much

alcohol, a lady and underwear for military dress code, General Hickman was

summoned to the ministry of defence at 7.45 am on the following Monday morning.

The co-minister of defence, Hilary Squires, had a file on his desk which

contained the full details. The minister, who had a puritanical streak at the

best of times, sacked Hickman on the spot. At 7.50 the general was out of a

job. (Hickman, who had won the MC in Malaya, later sued, and won, a case for

wrongful dismissal. Even though he had won his case on a technicality, he was

paid a year’s salary minus the pension he had received.) After Hickman’s

departure, the ministry of defence needed a ‘Mr. Clean’. The two choices as

Hickman’s successor were either Major General Derry McIntyre or Sandy Maclean.

McIntyre, although popular with his men, also had a reputation as a playboy, a

man who was described as ‘a cross between a cavalier and a hooligan’. Maclean

had a stable family background and, on the technicality that he was 12 days’

senior, was appointed the new army commander.

Hickman’s decision to contest his dismissal publicized the

problems in the army. Then Reid-Daly sued Hickman (and the minister of defence

and combined operations, Muzorewa, the directors of army military intelligence

and counterintelligence, the director of military police, and other senior

officers). As the court case dragged on to an inconclusive end, the normally

publicity-conscious Hickman dropped out of sight. The death from wounds of his

19-year-old son also severely affected him. A bitter Reid-Daly went to South

Africa, where he dabbled in a number of security firms and then, after helping

to write his own account of the war, became briefly the head of the Transkei’s

army.

In spite of the scandals surrounding two of Rhodesia’s

best-known soldiers, Lieutenant General Maclean tried to give the impression

that it was business as usual, for the army had to organize a massive security

screen for the April 1979 one-man, one-vote, election. More than 70,000 men

were involved in the country’s biggest mobilization. The security forces were

determined to prevent any PF disruption of the polls, but sometimes the

preventive counter-measures were heavy-handed. The security forces also took

the offensive across Rhodesia’s borders. On 13 April the SAS led an

Entebbe-style lt on the ZIPRA military command HQ in Lusaka (the Selous Scouts

had done the initial reconnaissance in the city). The raiders tried to smash

through the main gates in a Land Rover, but the padlock held the first time and

the vehicle had to be used a second time to batter through them. By this time

the ZIPRA guards were alerted and the SAS were pinned down by an RPD light

machine gun. The delay would have given time for Nkomo, who was thought to be

in the building, to escape. ComOps said that it wanted to destroy the ZIPRA

nerve centre, but an SAS source later admitted that the aim was to kill Nkomo.

Nkomo claimed that he had been at home and that he had escaped through a

lavatory window but this was untrue. So complete was the destruction of the

building that the ZIPRA leader could not have escaped. He must have been

elsewhere, allegedly tipped off by a British mole in CIO. Rhodesian troops also

sank the Kazangula ferry which was carrying ZIPRA military supplies from Zambia

into Botswana daily. At the same time commandos spirited away ZAPU men from

Francistown in Botswana and took them back to Salisbury. Not a single Rhodesian

soldier was killed in the dramatic attacks which were executed with total

efficiency and accuracy.

But ComOps regarded the April election as its crowning

success. Never had a ruling minority done so much to hand over (apparent) power

to a dominated majority. As one critical history, Rhodesians Never Die,

observed about the two elections which marked the end of white rule: ‘Rhodesia

buried itself with considerable integrity and maximum bureaucratic effort.’

Some Rhodesians, and most of the hundreds of pressmen in the country, expected

the April internal elections to be wrecked by PF attacks. Instead, the security

forces inflicted a high kill rate on the ZANLA forces which had concentrated in

the Chinamora, Mhondoro and other TTLs in the Salisbury area. Security forces

were deployed near all the static and mobile polling booths; for the first time

the auxiliaries were mobilized in a major supporting role in the rural areas.

Eighteen of the 932 polling stations were attacked, but none were closed. In a

64 per cent poll (if the population estimates were correct) 1,869,077 voters

took part. Even some guerrillas voted. In some areas ZANLA actively encouraged

the peasants to vote, although in most cases the PF tried to discourage any

involvement in the election. The diminutive bishop, Abel Muzorewa, won 51 of

the 72 black seats and so became the first African premier of the country. The

election was a success comparable to that in 1966 in war-torn South Vietnam. It

proved that the PF was nowhere near ‘imminent victory’ and that the security

forces were still powerful enough to mount a huge logistic exercise. If, as the

PF claimed, the turnout was the result of intimidation, it showed who

effectively controlled the population at that time.

Rhodesians believed implicitly in Margaret Thatcher’s

promise, when leader of the opposition, that she would recognize the April poll

if the Tory group of observers said the election was fair. The group, headed by

Lord Boyd, did indeed submit a favourable report, but the new British prime

minister reneged on her commitment. She was swayed by a Foreign Office

confidential paper outlining the possible repercussions of recognizing

Salisbury, plus personal pressure from Lord Carrington, her foreign secretary.

This was a catastrophic setback for Muzorewa. Many Africans rightly interpreted

it as lack of faith. If a Conservative British administration would not go

along with the internal settlement, who would? And the plain answer was–nobody.

The internal settlement’s goal had been to bring peace, recognition and the

removal of sanctions. The only tangible result was an escalation of the war.

When the bishop became prime minister on 1 June 1979 he assumed the additional

portfolios of defence and combined operations. By then ZANLA forces numbered

more than 20,000 in the country. Could Muzorewa survive ZANLA’s ‘Year of the

People’s Storm’?

The PF felt that military victory would come within one or

two years at the latest. But what if Western nations recognized Muzorewa and

channelled into Salisbury a vast array of military assistance? That would set

back the war by years. By mid-1979 ZANLA had amassed a large reserve of

conventional weaponry, although the variety of calibres and spares was proving

a major problem. (This had been a continuous difficulty; the logistic chain to

the forward-based guerrillas in Rhodesia, besides being poorly organized,

suffered from the heterogeneous nature of the supplies.) ComOps was aware of

the arsenal at Mapai, not far from the ZANLA base which the Rhodesians had hit

on a number of occasions. The weapons seemed to be set aside for a special

purpose which eluded Rhodesian intelligence. The arsenal had been intended at

one time, May 1979, to support Operation Cuba. This was a Cuban scheme to set

up a provisional government within a liberated area of Rhodesia. Many Eastern

bloc and Third World countries would have recognized it and thus have

pre-empted Western recognition of the Muzorewa administration. Mapai could have

supplied such a venture in the Chiredzi area, apparently ZANLA’s choice. ZIPRA

did not want anything to do with the plan and the Cubans withdrew their

support. The open terrain in the Chiredzi area and its proximity to South

Africa would have made a joint ZIPRA/ZANLA/FPLM/Cuban army an ideal target for

a Rhodesian and South African conventional counter-attack. The other area

mentioned in Operation Cuba, the north-east, would have been far more viable.

As it happened, the Cuban fear was unwarranted; not even

South Africa risked recognizing Muzorewa. But Pretoria did pour equipment,

pilots and ground troops into the very area set aside for Operation Cuba. And

with the promises of bonuses and security of pensions, many whites in the civil

service, security forces and police were persuaded to stay for another two

years. Yet after the brief euphoria of the April election, the whites grew

disenchanted with Muzorewa’s ham-fisted management of the new coalition

government. Even his own UANC split with the departure of James Chikerema’s

Zimbabwe Democratic Party. Then the bishop talked of encouraging skilled whites

to return, but demanded a levy of Rh$20,000. In a bizarre attempt to court

American opinion, he offered to welcome 1,000 Vietnamese ‘boat people’ to his

country, which had an African unemployment rate of 50 per cent. His biggest

failure was his ‘campaign for peace’. Muzorewa launched his amnesty programme

at the same time as he authorized the RLI to wipe out groups of mutinous

auxiliaries. Sithole’s men were particularly unruly in the Gokwe area. In this

area and others a total of 183 auxiliaries were killed. One group was gunned

down by troops hiding in the backs of troop carriers; another was lured into a

schoolhouse for a supposed meeting to thrash out discipline problems and was

obliterated in a strike by Hunters. Undoubtedly the government needed to

control the more lawless bands of Pfumo reVanhu, but to kill so many of what

the PF considered to be the bishop’s own force–just before the amnesty

launch–was catastrophic timing. Few PF guerrillas were impressed.

The Amnesty Directorate had been set up on 7 June 1979. It

was headed by Malcolm Thompson, the man who had masterminded the administration

of the April election. Thompson came from Northern Ireland, a territory not

exactly distinguished then for a tradition of fair elections or successful

ceasefires. The amnesty call included the exhortation to phone a series of

numbers across the country. Most of the numbers were UANC offices. A group of

journalists tried to phone these offices in the early evening; most of the

numbers were unobtainable because the offices were unmanned. The security force

aspects of the amnesty were much more professionally executed. Besides the

radio and TV campaigns, trilingual leaflets were scattered across the country.

The air force helped with ‘skyshouts’. Aircraft would suddenly swoop down on a

guerrilla camp. As the guerrillas ran to escape the expected bomb run they were

deafened by the blast from enormous tannoys which delivered a dramatic and

simple message: ‘You are about to be killed by the security forces. Give up and

live.’ Despite many possible personal doubts about the internal settlement,

guerrillas were severely punished by political commissars for listening to

amnesty broadcasts. They could be executed for reading an amnesty leaflet.

The internal leaders had promised peace after the March

Agreement, in 1978. Then they said the war would end after the one-man,

one-vote polls; then after the installation of a black premier…Eventually few

whites believed anything Muzorewa or Sithole said. Many emerged from their

cocoons of total reliance on ‘good old Smithy’. After the April election the

disenchantment in the army, particularly among the reservists, was widespread.

The bickering among the internal nationalists, which threatened to destroy all

the hard work the part-time soldiers and policemen had done, undermined their

loyalty. A number of white police reservists refused to guard Muzorewa’s house

the week after the April poll. They pointed out that the prelate had many

bodyguards while their own families went unprotected. No disciplinary action

was taken against the policemen. The real bone of contention was still white

conscription. Why should the bishop call up 59-year-old whites possibly hostile

to the UANC when he refused to conscript his youthful black followers? Only a

handful of blacks had been called up. The whites began to feel that their taxes

and skills were running the country and yet they were being compelled to fight

for a black administration which could soon steal their rights and property.

Another issue was the loyalty of the so-called ‘new Rhodesians’, the roughly

1,400 foreign mercenaries and volunteers in the regular forces. On the night of

Muzorewa’s election victory, Captain Bill Atkins, an American Vietnam veteran

who had been in the Rhodesian army for two years, said:

A good proportion of the foreign professionals [in the army]

will stay–we’re not mercenaries. If we find that we’re working with a guy we

disagree with, we will leave. We’re not here for the money. If they [the new

Muzorewa administration] back away from the war, as the Americans did in

Vietnam, then we’ll leave.

But no amount of reluctant military support from South

Africa, white Rhodesians or foreign levies could replace some kind of

international diplomatic support for Muzorewa. The PF rejected the new leader

as a stooge. As one ZANU official put it: ‘At least the leader of a so-called

Bantustan in South Africa can fire his own police chief.’ But Muzorewa could

not. Behind the facade, the whites were in control. Even Ian Smith was still

there in the Cabinet as a minister without portfolio. But the PF regarded him

as the minister with all portfolios. And the new Tory prime minister, Margaret

Thatcher, was still reluctant to recognize Muzorewa. At the Commonwealth

Conference in Lusaka in August, Mrs Thatcher secured the agreement of her

fellow premiers: an all-party conference would try for one last time to cut the

Gordian knot of the Rhodesian impasse. Muzorewa was bitter and Salisbury’s

Herald newspaper thundered: ‘Is Mrs Thatcher really a Labour Prime Minister in

drag?’

The Lancaster House conference opened on 10 September and

staggered on until just before Christmas. Both sides struggled to inflict

military reverses on their opponents, both to influence the course of the

three-month conference and to be in a commanding military position if diplomacy

should once again fail. As during the Geneva conference, the guerrillas talked

and fought, but this time there were four times as many guerrillas in the

country as in 1976. Within 48 hours of Muzorewa’s accession to power he had

authorized raids into his neighbours’ countries. Later, on 26 June, the

Rhodesians hit the Chikumbi base, north of Lusaka. Simultaneously five Cheetah

choppers dropped assault troops into the Lusaka suburb of Roma where they

stormed into the ZAPU intelligence HQ. It contained ZIPRA’s Department of

National Security and Order, which was commanded by Dumiso Dabengwa, whom

Rhodesian intelligence dubbed the ‘Black Russian’ because he was reputed to be

a KGB colonel. With the SAS was a senior ZIPRA captive, Elliott Sibanda. His

job was to use a loud hailer to get his former colleagues to surrender and then

identify whoever responded. During the fighting 30 ZAPU cadres and one SAS

captain were killed. Five hundred pounds of sensitive documents were seized

(including documents which, according to Muzorewa’s minister of law and order,

Francis Zindoga, proved that intelligence information had been passed to ZAPU

by white liberals). What had happened to the 150 tons of British air defence

equipment which had been sent to Zambia in October 1978 and the Rapier missiles

which the BAC team had repaired? Was it plain incompetence, or were the

Zambians afraid of protecting PF targets in case Salisbury decided to hit

directly at Zambian military installations?

On 5 September, five days before the Lancaster House

marathon began, Rhodesian forces hit ZANLA bases in the area around Aldeia de

Barragem, 150 km north-west of Maputo. This was part of a new strategy: instead

of just targeting PF military bases, Salisbury escalated its strikes to include

the economic infrastructures of both Zambia and Mozambique. The attacks on

economic targets, especially dropping bridges, were a small part of the ComOps

‘final solution’ plan. The highly secret proposals estimated that both

Mozambique’s and Zambia’s economic structures could be destroyed within six

weeks. The techniques to be used would have gravely escalated the war and

almost certainly brought in the major powers. ComOps demanded a clear political

green light for total war on Zimbabwe-Rhodesia’s neighbours. If Muzorewa had

been recognized after a possible breakdown of the Lancaster House talks, then

the plan might have been put into action. Instead, only small parts of the

scheme were used. It was then poorly organized. Major setbacks resulted and

Walls was privately criticized by senior commanders for undue interference,

particularly regarding the choice of targets. Some of the final raids were not

planned by Walls or the CIO chief, who often had the final say, because both

men were in London for most of the Lancaster House talks. Several raids had to

be publicly supported by them even though they had been carried out against

their better judgment.

In September the Rhodesians tried to destroy much of the

transport sy stem in Mozambique’s Gaza province, and beyond. More bridges were

destroyed by SAS and South African Recce Commandos. Then Salisbury stopped the

rail supplies of maize to Zambia through Zimbabwe-Rhodesia. In October and

November vital Zambian road and rail arteries were hit. The aim was two-fold:

to stop the infiltration of PF guerrillas and supplies, and to induce the

frontline states to pressurize the PF into accepting a more conciliatory line

towards the Salisbury delegation in London. But such a strategy was not without

its costs. ZIPRA had improved with the aid of Cuban, East German and Russian

instructors. And FRELIMO had added a stiffening to ZANLA forces. In Zambia the

regular army was too small and ineffective to give much conventional support to

ZIPRA in its defence against Rhodesian raids, but in Mozambique the position

was quite different. The ZANLA bases there were well defended.

The Rhodesian raids were now no walkover. In the three-day

Operation Uric (Operation Bootlace for the South Africans) in the first week of

September the Rhodesians were determined to stop the flow of both ZANLA and

regular FPLM soldiers infiltrating across what the Rhodesians nicknamed the

‘Russian Front’. The target was Mapai, the FRELIMO 2nd Brigade HQ and a control

centre for ZANLA, a very heavily defended forward base 50 km from the border.

Conventional military thinking dictated that in, addition to air support, two

infantry battalions supported by artillery and tanks would have been required.

As ever, the Rhodesians would make do with far less, relying on the shock of

air power, surprise and courage. The aerial order of battle included: 8

Hunters, 12 Dakotas (half SAAF), 6 Canberras (of which 4 were South African),

10 Lynxes and 28 helicopters, including the newly acquired, but worn-out,

Cheetahs (Hueys) along with a majority provided by the SAAF: Pumas, Super

Frelons and Alouettes. A Mirage and Buccaneer strike force was on cockpit

readiness in South Africa, and a battalion of paratroopers, with Puma

helicopter transport, was on standby at a base near the Mozambique border. The

command Dakota, the Warthog, was equipped with an advanced sensor system

capable of locating and monitoring the guidance systems of ground-to-air

missile installations and identifying surveillance radar systems. The crew

included an intelligence officer and four signallers for communications with

friendly forces. The plane was piloted by John Fairy, a scion of the famous

British air pioneers. The SAAF had its own AWACS aircraft, a converted DC-4,

nicknamed Spook. This was the largest single commitment of the SADF in the war.

The Canberras normally carried the cylindrical

Rhodesian-designed Alpha bombs. But these had to be released in level flight,

when flying at an air speed of 350 knots and at 300 metres above the ground.

When they struck they bounced four metres into the air and exploded, sending

out a deadly hail of ball bearings. The flak at Mapai was so heavy they would

have been blown out of the sky if they tried a low-level attack. So the SAAF

supplied conventional bombs which were dropped at 20,000 feet. A heliborne

force of 192 troops went in after the bombers. In all the raiders numbered 360

men in the field, from the SAS, Recce Commandos, RLI and the Engineers. They

met very fierce opposition. The fire from the 122mm rockets, mortars,

recoilless rifles and machine guns from the entrenched ZANLA/FPLM enemy was

intense, the heaviest the Rhodesians had ever encountered. All they had,

besides air power, were 82mm and 60mm mortars, RPG-7s, light machine guns and

their personal weapons. Soon the battle developed into a grim face-to-face

encounter in trenches. The defenders stood and fought, and showed no intention

of running from the air power, as they had so many times previously. General

Walls, in the Warthog above the battle, wanted a victory not a defeat to accompany

the politicking at Lancaster House. Nor did the South Africans want to commit

their reserves and so not only risk defeat, but also reveal the extent of their

cross-border war with Mozambique.

Two helicopters were shot down. The first was a Cheetah, hit

by an RPG-7. The technician was killed, but the badly wounded pilot was

extricated by a quick-thinking SAS sergeant. The second, an SAAF Puma, was

downed by another RPG-7; the three air crew and 11 Rhodesian soldiers were

killed. One of the dead was Corporal LeRoy Duberley, the full back of the

Rhodesian national rugby team. The remains of the wrecked Puma were later

golf-bombed in a vain effort to destroy the South African markings. Seventeen

soldiers were killed in Operation Uric. Walls called a stop to the operation.

This was the worst single military disaster of the war. And, for the first

time, the Rhodesians were unable to recover the bodies of their fallen

comrades. As a book on the Rhodesian SAS later noted: ‘For the first time in

the history of the war, the Rhodesians had been stopped dead in their tracks.’ The

RLI and the SAS were forced to make an uncharacteristic and hasty retreat.

The Rhodesians had underestimated their enemy. They were

outgunned. Their air support had proved unable to winkle out well-entrenched

troops and they were even more vulnerable when the aircraft–even when the whole

air force was on call–returned to base to refuel and rearm. Combined Operations

had decided to use more firepower. Surveillance from the air was stepped up by

deploying the Warthog. The South African air force became heavily involved in

these last months, both in the fighting and as standby reserves, as in the case

of Operation Uric in September 1979. Super Frelons and Puma helicopters were

difficult to pass off as Rhodesian equipment, but the Canberras and Alouettes

also on loan were practically indistinguishable from their Rhodesian

counterparts, except when they were shot down. The combined Rhodesian-South

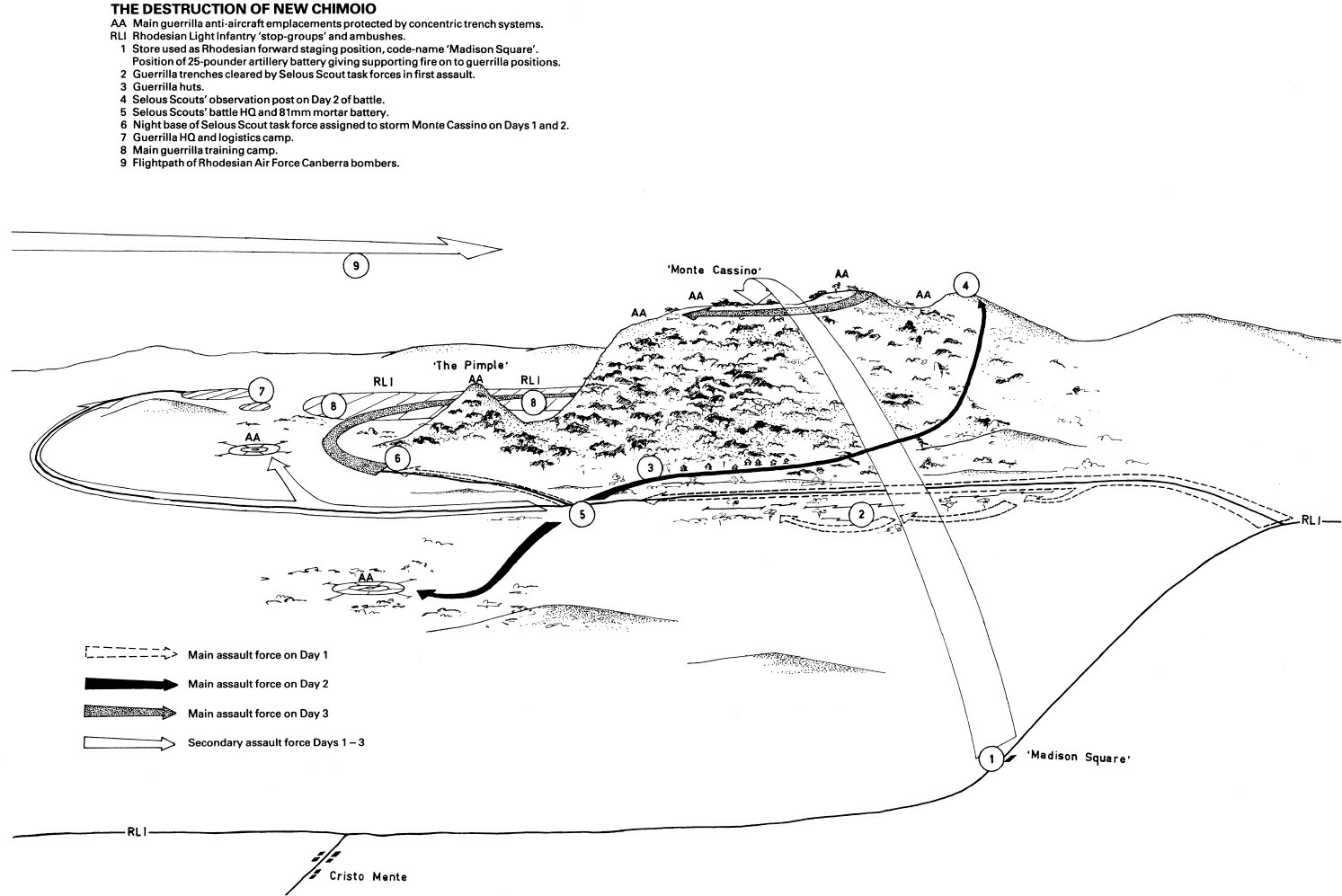

African efforts were approaching all-out war in the region. In late September,

the Rhodesians hit the reconstituted ZANLA base known as New Chimoio. They also

hoped to kill Rex Nhongo, the ZANLA commander, who narrowly escaped the first

air strikes. ComOps claimed that this operation (Miracle) was a success, but

the air force lost an Alouette, a Hunter and a Canberra. At the end of the

climactic raid on New Chimoio, one Selous Scout admitted: ‘We knew then that we

could never beat them. They had so much equipment and there were so many of

them. They would just keep coming with more and more.’ The Rhodesians also

attempted to stall the conventional ZIPRA threat to Kariba. RLI and SAS troops

found themselves outgunned during this operation (Tepid). ZIPRA forces stood

their ground, although they did eventually make an orderly withdrawal. On 22

November Walls ordered ComOps to stop all external raids.

The political warfare at the conference table was almost as

bitter as on the real battlefields in southern Africa. The PF haggled over

every step of the negotiations. Muzorewa had conceded easily. But Ian Smith had

to be brought into line by the toughness of Lord Carrington, the conference

chairman, as well as by a series of lectures from Ken Flower, General Walls and

D C Smith, the RF deputy leader. David C Smith had played a pivotal role.

Bishop Muzorewa had not wanted to include Ian Smith in his delegation to

London, but David Smith had talked the bishop into it and said that he himself

would not go if the RF leader were excluded. But Ian Smith’s presence was

counterproductive for the Salisbury team. The RF chief did his best to

undermine the bishop’s leadership. Gradually the PF was pushed into a

diplomatic corner. The British had bugged all the hotel suites, especially the

PF’s, and knew exactly how far to push the guerrilla leaders. The Rhodesians

realized that their hotel was bugged and sometimes used an irritating device

which made squawking noises to hide conversations. More often they talked about

confidential matters out-of-doors. Lord Carrington told the PF he would go

ahead and recognize Muzorewa if the conference broke down. None of the

frontline states wanted the war to continue and they exerted a continuous

leverage on the hardline PF coalition. Josiah Tongogara, who had more influence

over ZANLA than did Mugabe, believed that a political compromise was possible.

Nyerere also urged moderation and he persuaded Britain that more than

‘metaphysical’ force was needed to set up a ceasefire monitoring group. Samora

Machel was also a vital ally of Carrington’s. In spite of Mugabe’s threats to

go back to the bush, Machel privately told him that he wanted peace, and

without Mozambique as a sanctuary ZANLA would collapse. Machel told Mugabe: ‘We

FRELIMO secured independence by military victory against colonists. But your settlers

have not been defeated, so you must negotiate.’ Angola, Nigeria and Zambia, for

different reasons, wanted a speedy end to the conflict. There had been too much

suffering for far too long.

If the guerrillas had not been put in an arm-lock by their backers,

especially in Mozambique, and had walked out of the conference, Lord Carrington

had warned that he would go for the ‘second-class solution’: recognition of

Muzorewa. Paradoxically, the very success of the military raids, especially on

the economic infrastructure (including the SAS-Recce Commando raid on Beira

harbour on 18 September), was probably politically counter-productive. The

raids raised the morale of the white hardliners in Salisbury, but it ensured

that the frontline states kept the PF sitting around the table. A tactful lull

in the externals might well have prompted Mugabe to go for the unconditional

surrender option, and walk out, and thus force Carrington to hand the baton to

Muzorewa.

On 12 December Carrington took a gamble and sent Lord Soames

as the new British governor of Rhodesia. Britain was officially in full

control, for the first time in the colony’s 90-year history. It was a highly

risky venture–‘a leap in the dark’ in Soames’s own words. Final agreement on

the complete process of drafting a new constitution, a return to British rule,

a ceasefire and a new election had not been reached. But the rebellion was

over. As soon as Lord Soames stepped down on Rhodesian soil, the revolt against

the British Crown was quashed and sanctions were removed. But the civil war

went on.

Walls had long predicted privately that the war would end in

a military stalemate, and so it was. On 21 December 1979, after an epic of

stubborn last-stands, all parties to the conference signed the final agreement.

Ironically, it was exactly seven years to the day since the real war had begun

with the attack on Altena farm in the Centenary district. Robert Mugabe was

resentful. He said later: ‘As I signed the document, I was not a happy man at

all. I felt we had been cheated to some extent, that we had agreed to a deal

which would… rob us of the victory we had hoped we would achieve in the field.’

On 28 December the ceasefire creaked uncertainly into life.

By 4 January 1980 more than 18,000 guerrillas had heeded the ceasefire and had

entered the agreed rendezvous and assembly points inside Zimbabwe-Rhodesia.

Just as the ceasefire began, one of the main architects of compromise, Josiah

Tongogara, was reported killed in a motor accident in Mozambique. As the most

prominent soldier on the ZANLA side, his voice of moderation–especially

regarding relations with ZIPRA–would be sorely missed. Because ‘motor

accidents’ had been staged throughout the Rhodesian saga as a means of removing

opponents, ZANU went out of its way to try to prove the incident an accident;

even to the extent of sending a white employee of a Salisbury funeral service

to Maputo to embalm the body. But a strong suspicion of murder lingered at the

time. Nevertheless, no firm evidence of this has surfaced, though ZIPRA was

convinced that an East German specialist in ‘road accidents’ had arranged

Tongogara’s demise. Later, even in ZANLA, it was accepted that he had been

murdered. Senior ZANU men had agreed to his removal because of several general

factors, including his desire to work closely with ZIPRA and his emphasis on

encouraging whites to remain in the country. But the specific reason may have

been his alternative plan, discussed privately during the Lancaster House

talks, if the conference had failed. He argued that the three main armies

(ZIPRA, ZANLA, the Rhodesian security forces) could guarantee a peaceful,

five-year transition to civilian rule. A council of four parties (the RF, UANC,

ZANU and ZAPU) would provide the administration, with a council of the military

leaders acting as a watchdog. During this period the armies would be

integrated. Then, after five years, or sooner if the integration was completed,

elections would be held. Sir Humphrey Gibbs was suggested as a compromise

candidate for the transitional presidency. ZIPRA apparently went along with the

plan, but the constitutional conference reached agreement before Walls could be

consulted by Tongogara. With hindsight such a plan appears bizarre, but it

certainly paralleled Tongogara’s public demands for conciliation.

Certainly some reconciliation would be needed to rebuild the

devastated country. The long war had exacted a sad toll. More than 30,000

people had been killed (though some historians have offered a lower figure).

Operation Turkey had destroyed a vast acreage of peasant crops to prevent food

reaching the guerrillas. The International Red Cross estimated that 20 per cent

of the seven million black population was suffering from malnutrition. More

than 850,000 people were homeless. The maimed, blinded and crippled totalled at

least 10,000. The Salvation Army reckoned that of the 100 mission hospitals and

clinics which served the rural population, 51 were closed, three had been burnt

to the ground, and most of the others were badly damaged and looted. More than

100,000 men in the towns were unemployed. At least 250,000 refugees waited to

be repatriated from camps in the frontline states. About 483,000 children had

been displaced from their schools; some had gone without schooling for five

years. Half the country’s schools had been closed or destroyed. Finding a real

peace was only half the problem; a massive reconstruction programme would have

to follow.

Many outside observers and most whites in Rhodesia expected

the fragile truce to erupt once more into full-scale war which a British

governor with only 1,300 Commonwealth troops would have to contain. Ninety-five

per cent of the country was under martial law when Soames arrived. Extra regular

troops had entered the conflict. FPLM soldiers from Mozambique were fighting

alongside ZANLA. On the other side, the South African army’s commitment had

grown. By November 1979, South Africans were operating in strength in the

south-east, particularly in the Sengwe TTL and along the border. They were

supplied by air from Messina and their HQ was at Malapati. They were using

artillery bombardment to create guerrilla movement, a technique the Rhodesians

could not afford with 25-pounder shells costing $150 each. By December the SADF

was operating north of Chiredzi. The aim was to put one battalion, each with a

company-sized Fire Force, into each major operational area, making the total

commitment five battalions. The news of South African involvement was deliberately

leaked to boost sagging white morale.

If the ceasefire collapsed, more foreign regulars would be

sent to fight in the civil war, a war that could have engulfed southern Africa.

A grave responsibility rested on the man at the epicentre of the storm: Lord

Soames, who had no previous experience of African affairs. As the London

Observer warned: ‘A bomb disposal expert would be the best British Governor to

send to Zimbabwe-Rhodesia. The country lies ticking, a black and white booby

trap with many detonators. ’Would the ceasefire hold?’