Hood agreed that Nelson might take the town with five

hundred troops backed by three ships of the line from Hood’s squadron but

doubted that Nelson could take the heights as well. Hood therefore went back on

shore from Victory two days after his first meeting with Dundas to press the matter

with him again. But he got no further: Dundas refused even more vehemently than

before, declaring that an attack on Bastia was impracticable without the

reinforcement of two thousand troops requested from Gibraltar, adding ‘I

consider the siege of Bastia, with our present means and force, to be a most

visionary and rash attempt, such as no Officer could be justified in

undertaking.’ Dundas’s force consisted of sixteen hundred regulars and 180

artillery men. Nelson’s estimate of the strength of the French in Bastia had

been one thousand regulars and fifteen hundred ‘irregulars’, the latter

Corsicans.

Hood’s written reply to Dundas was sharply edged: ‘I must

take the liberty to observe, that however visionary and rash an attempt to

reduce Bastia may be in your opinion, to me it appears very much the reverse,

and to be perfectly a right measure…and I am now ready and willing to undertake

the reduction of Bastia at my own risk, with the force and means at present

here, being strongly impressed with the necessity of it.’2

Faced by that intractable declaration of intent Dundas

resigned his command. Unfortunately for Hood the successor to the command,

General d’Aubant, shared Dundas’s views. And he unrelentingly stuck by them. He

not only refused soldiers for an assault on and siege of Bastia but also

withheld from Hood mortars, field guns and ammunition from the stores he

controlled at Fiorenzo. Hood was compelled to send to Naples for the materiel

he lacked. But he exercised his own powers by recalling on board his ship’s

soldiers from four regiments who had previously been allocated to him to do

temporary service as marines and whom he had loaned to Dundas for the capture

of Fiorenzo. Since these soldiers were now registered as part of the

complements of the ships aboard which they were quartered d’Aubant was unable

to refuse to release them.

The siege of this remote Corsican fortress of Bastia became

bitter infighting between the Royal Navy and the army. With the soldiers under

d’Aubant’s command confined to their garrison in Fiorenzo, this was the navy’s war

or, so to speak, Hood’s and Nelson’s personal campaign. For Nelson, Bastia had

to fall, and soon. To him the attitude of the army in refusing to join with

Hood in the assault was incomprehensible. ‘Not attacking it I could not but

consider as a national disgrace. If the Army will not take it, we must, by some

way or the other.’

Through March Nelson maintained the blockade of Bastia, with

Agamemnon riding out near-continuous gales and thick weather. From his

storm-lashed quarterdeck Nelson angrily watched the town daily strengthening

its defences: ‘…how that has hurt me’. Some of the hardship he was imposing

upon Bastia was being experienced aboard Agamemnon as well. On 16 March he

reported to Hood, ‘We are really without firing, wine, beef, pork, flour and

almost without water: not a rope, canvas, twine or nail in the ship…We are

certainly in a bad plight at present, not a man has slept dry for many months.’

As postscript to that same note in his journal he added, ‘But we cheerfully

submit to it all, if it but turns out for the advantage and credit of our

country.’ Holding on was critical for Nelson personally, his fear being that if

Agamemnon were compelled to go to Leghorn for stores he would lose his own role

in the attack on Bastia. He was in something like near panic over missing out

on another land operation, one so closely involving his own efforts and

persuasion. He put it to Hood, ‘My wish is to be present at the attack of

Bastia; and if your Lordship intends me to command the Seamen who may be

landed, I assure you I shall have the greatest pleasure in doing it, or any

other service where you may think I can do most good: even if my ship goes into

port to refit, I am ready to remain.’ Hood responded and Agamemnon’s

deficiencies were supplied from the squadron and other sources.3

Nelson, together with an army artillery officer and an army

engineer, then made steady reconnaissance ashore to decide landing beaches and

sites for batteries northward of Bastia. He pitched a tent on a beach with the

union flag hoisted above it, and was thereafter in continual movement between

tent and Agamemnon. His presence on land was constant because his sailors, with

others from the squadron, were building batteries, clearing roads and hauling

guns and ammunition to the batteries. Like the earlier effort, it was a

phenomenal task dragging guns up those rocky and precipitous heights, requiring

physical strength and stamina that astonished all who witnessed it. ‘It is very

hard service for my poor seamen, dragging guns up such heights as are scarcely

credible,’ Nelson wrote. And, after his sailors had dragged guns to a pinnacle

just seven hundred yards from the town, he described it as a feat ‘which never,

in my opinion, would have been accomplished by any other than British seamen’.

Hood took full command on 4 April, though preparation for

the siege remained with Nelson. By 11 April three batteries equipped with

sixteen heavy guns and mortars were ready to open fire on Bastia. Hood sent in

a flag of truce demanding surrender. The answer he got from La Combe St Michel,

Corsica’s commissioner, was defiant: ‘I have hot shot for your ships and

bayonets for your troops. When two-thirds of our troops are killed, I will then

trust to the generosity of the English.’

The battle for Bastia began at once. Navy and Bastia began

pouring shot and mortars upon one another. The cannonade was immense. From

commanding positions over the town, the citadel and the outworks five British

24-pounders, four mortars and two heavey carronades poured their fire while the

ships opened up from the sea. Thus it was to remain through April and on into

the third week of May. Bastia continued to hold out defiantly, in spite of the

destruction raining upon it and the starvation afflicting its garrison and

populace.

Bizarrely, throughout the campaign General d’Aubant and his

officers had simply stood by as interested observers.

On 19 May the French asked for negotiation. A boat went from

Victory to the town. ‘The enemy met us without arms, and our officers

advancing, they shook hands, and were good friends: they said it was all over,

and that Bastia was ours,’ Nelson recorded in his journal. General d’Aubant and

the soldiers from Fiorenzo simultaneously appeared on the hills above the town.

They were there because reinforcement had just arrived from Gibraltar. They

then proceeded to occupy Bastia and all its outposts.

The garrison was far stronger than Hood believed and had

held out longer than expected. Nelson, however, had known. He knew it two

months before the siege began. Here, then, was the near-fearful recklessness

that ever pulsed in this extraordinary man. He had got the information from a

packet boat intercepted by Agamemnon. The mailbag on board contained a letter

from Corsica’s commissioner, General La Combe St Michel, declaring that he

needed subsistence for eight thousand French and Corsican soldiers. This was

four times as many as estimated by Nelson and Hood, but Nelson kept that

critical information to himself. He rightly believed that disclosure would set

Hood against any assault against Bastia. It would embarrassingly confirm

Dundas’s verdict that such an attack would be ‘visionary and rash’. Failure to

attack had been insufferable to Nelson. It went wholly against his disdain for

holding off and failing to try. There was as well the conviction that his

sailors could master any situation given the proper leadership and motivation.

Had he persuaded Hood into the sort of landing that he had

cried out for at the start it could have finished them both, for they likely

would have suffered heavy loss in the attack. This provided illustration of the

length to which Nelson was prepared to go, whatever the risk and circumstances,

to ensure action for himself. It worked at sea, and much of his future glory

would be based upon it. But he never learned the point that Napoleon, in his

memoirs, made on the difference at battle scene between land and sea: ‘A marine

general has nothing to guess; he knows where his enemy is, and knows his

strength. A land general never knows anything with certainty, never sees his

enemy plainly…When the armies are facing each other, the slightest accident of

the ground, the least wood, may hide a party of the hostile army. The most

experienced eye cannot be certain whether it sees the whole of the enemy’s

army, or only three fourths of it…The marine general requires nothing but an

experienced eye; nothing relating to the enemy’s strength is concealed from

him.’4 A year after Bastia had fallen Nelson was to confess, ‘I never yet told

Lord Hood that…I had information given me of the enormous number of troops we

had to oppose us; but my own honour, Lord Hood’s honour, and the honour of our

country must have all been sacrificed, had I mentioned what I knew.’5 He had

been prepared for that risk, and would be again. And in his correspondence on

this matter he described as well as he ever would the settled principles that

drove him: ‘I feel for the honour of my country, and had rather be beat than not

make the attack. If we do not try we can never be successful…My reputation

depends on the opinion I have given; but I feel an honest consciousness that I

have done right. We must, we will have it, or some of our heads will be laid

low. I glory in the attempt,’ he told his wife in one of his many assertive

letters at the time. Or, on another occasion, ‘My disposition cannot bear tame

and slow measures.’ Also, ‘…our country will, I believe, sooner forgive an

officer for attacking his enemy than for letting it down’. And, in response to

his wife’s continual fears over his safety, ‘Only recollect that a brave man

dies but once, a coward all his life long.’

At all events, Bastia had been won. He and his sailors had

done it. ‘The more we see of this place, the more we are astonished at their

giving it up,’ Nelson said. Starvation was probably the greatest factor in

compelling early surrender. On that point at least General Dundas has been

insightfully correct.

The surrender and occupation of Bastia and its fortifications

were complete by 22 May. The army had taken over, under Lieutenant Colonel

Villettes, and for Nelson what had been his operation no longer was. An attack

was about to be launched against the other fortress, Calvi, and he saw his own

role diminished and uncertain. Although Hood had allowed Nelson a free hand

while the army held off, he had never in any way defined Nelson’s command. In

the new circumstances Nelson saw himself at a disadvantage with the army. He

was, he said in a letter home, ‘everything, yet nothing ostensible’.

Nelson then put his unease to Hood: ‘Your Lordship knows

exactly the situation I am in here. With Colonel Villettes I have no reason but

to suppose I am respected in the highest degree…but yet I am considered as not

commanding the seamen landed. My wishes may be, and are, complied with; my

orders would possibly be disregarded. Therefore, if we move from hence, I would

wish your Lordship to settle that point.’

Hood gave sympathetic acknowledgement without, however,

issuing any decisive clarification of the sort Nelson wanted. Hood had already

had too many difficulties with the army without inviting more. The idea of

conceding clearly defined authority to Nelson as his man there may have raised

fear in Hood of Nelson’s impatience and impetuosity provoking trouble with the

army.

For Hood defeat at Toulon had been followed, after much

uncertainty, by triumph at Fiorenzo and Bastia. Towards Calvi all now directed

their attention. There was no basis for doubting another imminent triumph there

as well. Hood was in poor health and expected soon to be going home. He would

wish to return expecting the sort of salutation and honours that these

successes would ensure. He now possibly believed that Nelson’s energetic and

impulsive bravado needed to be subdued. Hood was by this time certainly aware

of the possible loss that might have been suffered had he yielded to Nelson’s

early impetuous conviction that Bastia might be won by merely five hundred

seamen. Nevertheless, he had benefited in the end from that impetuosity. What

Hood’s reputation had gained here he owed to Nelson. Difficult therefore to

understand what Hood now officially delivered concerning Nelson’s part at

Bastia.

Aboard Victory lying off Bastia, on 22 May Hood wrote his

first report, his general order of thanks directly to the participants in the

action. It was brief, direct. ‘The commander in chief returns his best thanks

to Captain Nelson…as well as to every officer and seaman employed in the

reduction of Bastia…’ But when Hood sat down and composed his official report

to the Admiralty his tributes were framed differently.

Hood’s report to Admiralty began with particularly fulsome

praise for ‘the unremitting zeal, exertion and judicious conduct’ of Colonel

Villettes. As for the other army officers, ‘their persevering ardour, and

desire to distinguish themselves, cannot be too highly spoken of; and which it

will be my pride to remember to the latest period of my life’. Then, ‘Captain

Nelson, of His Majesty’s ship Agamemnon, who had the command and direction of

the seamen, in landing the guns, mortars and stores; and Captain Hunt, who

commanded at the batteries…have an ample claim to my gratitude; as the seamen…’

This praise for Hunt particularly riled Nelson, for Hunt was a protégé of Hood

who had made minimal contribution to their success.

Apart from the spareness of the praise in comparison with

that which extolled the army officers, for Hood to have so limited Nelson’s

part in all of it to that of a mere supervisor of the landing of guns and

stores coldly denigrated the whole of Nelson’s extraordinary achievement there,

ignored Hood’s own faith in and dependence upon him, dismissed the boldness and

endurance that had helped to establish their very presence on the Corsican

coast.

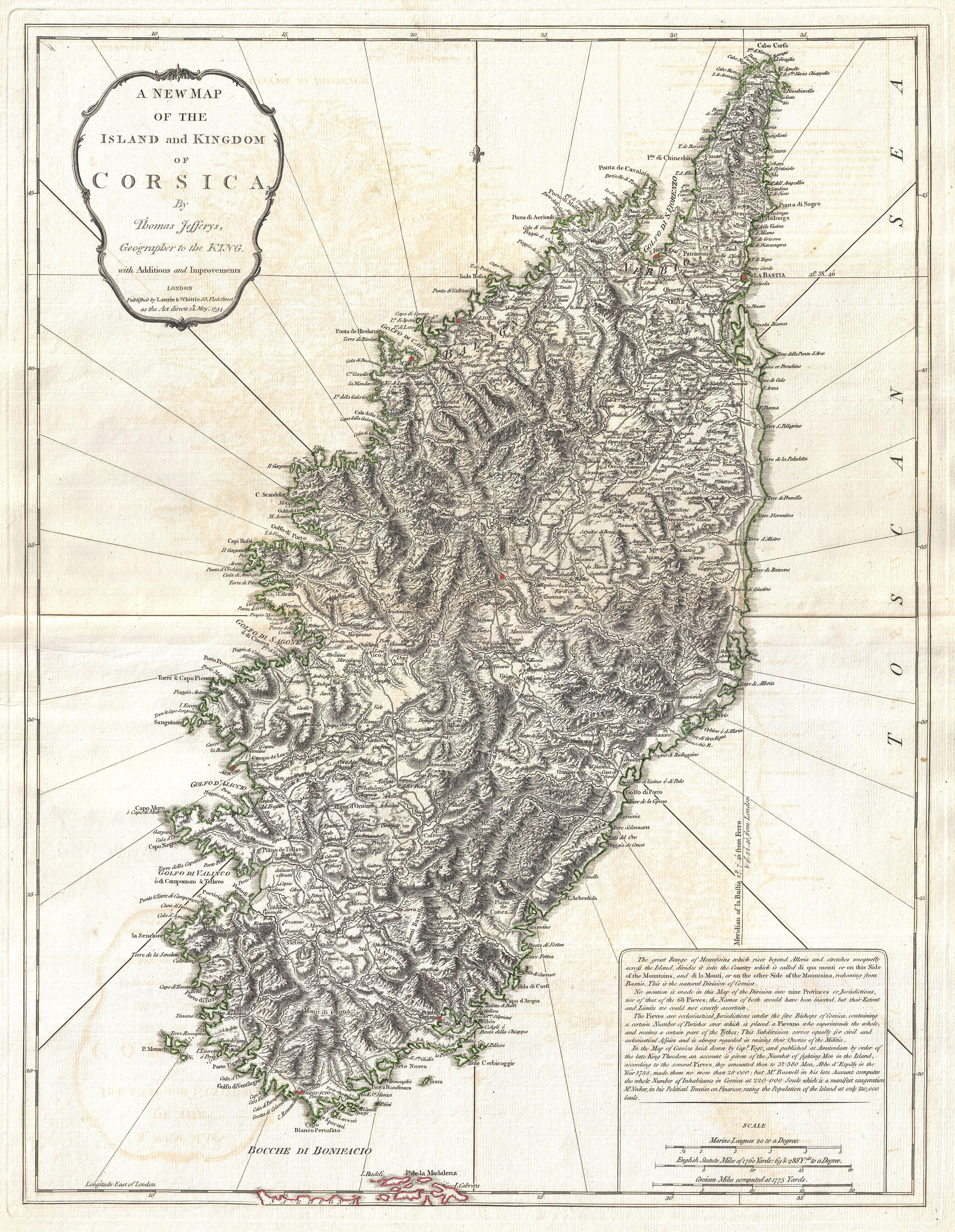

Lord Nelson, John Hoppner, c.1805. RNM. The Corsican campaign is often credited as the first in which Nelson rose to prominence within the Royal Navy

Like the others, Nelson saw Hood’s initial congratulatory

General Order at once. But it would be several weeks before copies of the

Admiralty report reached him. When it did it was to be a jolting shock.

Regardless of that brutal insensitivity and lack of consideration, it was

nevertheless Hood’s gift of responsibility on Corsica that finally meant

everything. For here on Corsica in the first half of 1794 began the remarkable

ascendancy in this war of this unique character, Horatio Nelson. So much of

what was to mould his greater role in such a determining war was cast here. In

Corsica Nelson drew upon himself the sort of command he sought in which to

exercise his independence and express the individuality so vital to him. The

conquest of Corsica was Nelson’s achievement. Land battle thus arrived before

sea battle for Nelson in this war. He had had his first action at sea, a small

encounter on the way to Tunis, but what he ardently longed for was to be part

of the confrontation between the French and the British navies on that large

and decisive scale that might settle the issue on this sea and on the ocean

beyond. That was yet distant.