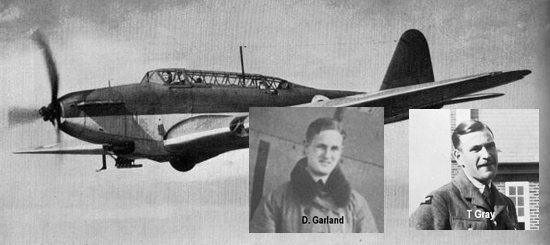

Donald Edward Garland and Thomas Gray with a Fairy Battle.

One of the 12 Squadron

aircraft shot down on 12th May 1940. Fighter bomber Fairey Battle P2332 PH-F

airborne 0818 from Amifontaine. It was tasked to destroy the concrete bridge

spanning the Albert Kanaal at Vroenhoven. Shot down by Flak and fighters and

crashed near the bridge, 24 km SE of Hasselt, Belgium. The crew of three were

made prisoners of war.

12 May 1940

Since its inception by Queen Victoria in 1856, the Victoria

Cross has rightly taken precedence over all other awards within the British

Commonwealth. Its award exemplifies unadulterated valour, in which rank or

class plays no part. The fact that the award was made to airmen on just

thirty-two occasions during the Second World War is an indication of its rarity,

and for two members of the same crew to each receive a VC is unique. And so the

story of daring raids rightly starts with these two men, Donald Garland and

Thomas Gray: the pilot and observer of a Fairey Battle, who so gallantly faced

a seemingly impossible task.

The Fairey Battle was a single-engine light bomber. It was

powered by the same Merlin engine that gave the RAF fighters, the Spitfire and

Hurricane, such great speed and performance, but, unlike the fighters, the

Battle was weighed down by a three-man crew and an internal bomb load of four

250lb bombs. Although it had a rather sleek appearance, the Battle was 100mph

slower than the new generation of fighters entering service, was limited in

range, lacked manoeuvrability and was extremely vulnerable to anti-aircraft

fire from the ground. In the air, its defence consisted of a single machine gun

in the starboard wing and another mounted in the rear cockpit. In truth, the

Battle was an obsolete aircraft, but had been retained by the RAF at the outbreak

of war as there was no adequate replacement at the time.

For the aircrew of 12 Squadron, the first eight months of

the Second World War had proved relatively uneventful. Since being rushed to

northern France at the outbreak of war as one of ten short-range bomber

squadrons of the RAF’s Advanced Air Striking Force, operations had been

relatively few and far between and had been limited to a series of

reconnaissance missions. The squadron had become settled at its grass airfield

near the village of Amifontaine, some 25 miles north-west of Rheims.

Then, during the early hours of 10 May 1940, everything

changed. The period that has since become known as the Phoney War came to a

sudden and dramatic end as German forces attacked northern France and the Low

Countries. The main German thrust had seen its armoured units cut-off and

surround Allied units in Belgium and, in doing so, they had captured several

vital bridges spanning the Albert Canal.

Two of these bridges were on the Dutch/Belgian border at

Vroenhoven and Veldwezelt, on the western side of Maastricht. On the morning of

12 May, volunteers from 12 Squadron were called on to carry out a short-notice

and high-priority raid. The volunteers that came forward had no idea of what

the raid would involve and had been given no time to prepare; as the six crews

made their way to briefing they were still coming to terms with the squadron’s

losses on the opening afternoon of the German offensive, just two days before,

when three of the four Battles sent out to bomb enemy positions advancing

through Luxembourg had failed to return.

As the volunteers listened to the briefing they soon

realized they were facing a most daunting task. Their targets were two bridges

at Maastricht, the ones at Vroenhoven and Veldwezelt, which had not been

destroyed by retreating ground forces and were now allowing German forces to

pour into Belgium. Tasked with leading a first section of three aircraft to

attack the concrete bridge at Vroenhoven was Flying Officer Norman Thomas,

while the second section, with the task of attacking the metal bridge at

Veldwezelt, was to be led by a 21-year-old Irishman, Flying Officer Donald

Garland.

Having captured the bridges intact, the Germans were not

prepared to let them be destroyed and so considerable resources, including

anti-aircraft guns and fighter cover, had been allocated to their protection.

The Battle crews were, therefore, briefed to expect Hurricanes over the target

area, with the task of sweeping ahead of the Battles and engaging any Luftwaffe

fighters lurking in the vicinity.

Thomas and Garland formed their plan. They decided to carry

out different types of attack to give the enemy defences more of a problem,

which would hopefully give the Battle crews more chance of success rather than

having all six aircraft approach Maastricht at the same height and at the same

time. Thomas elected to lead his section to the target at 6,000 feet and to

then carry out a diving attack on the bridge at Vroenhoven, while Garland chose

to approach and attack the bridge at Veldwezelt from a low level.

It was just after 8.00 am when the crews climbed into their

Battles at Amifontaine. One aircraft was unserviceable and so Thomas would have

to carry out the attack on the bridge at Vroenhoven as a pair, with the other

Battle flown by 20-year-old Pilot Officer Tom Davy. Minutes later the Battles

were climbing away towards Maastricht. Meanwhile, eight Hurricanes were getting

airborne from nearby Berry-au-Bac, but instead of being the hunters and

sweeping the area in readiness for the Battles, the Hurricanes soon became the

hunted as a large formation of Messerschmitt Bf 109s swooped down upon them.

The two Battles arrived in the target area to find the

Hurricanes were already fighting for their own survival and could not offer any

fighter protection at all. The task facing the Battle crews was now greater

than ever. As Thomas and Davy approached Vroenhoven they were soon spotted by

the German defences on the ground and an intense barrage of flak opened up.

Through the smoke and patches of cloud they could see their target but they

were then spotted by the 109s defending the bridges.

Undaunted and completely focused on their task, Thomas and

Davy commenced their attack from the south-west. As the two Battles headed

towards their target they soon found they were also running the gauntlet of

enemy fighters as they dived down through the anti-aircraft fire towards the

bridge. Both Battles were hit repeatedly during their attacks but Thomas and

Davy managed to press on towards the bridge, finally releasing their bombs before

turning away in a desperate bid for safety.

Although their bombs hit the target, causing some damage to

the structure, the bridge remained intact. Now badly hit and struggling to

maintain any control of his aircraft, ‘PH-F’, Thomas could not make it back to

friendly lines and ordered his two crew members, Sergeant B. T. P. Carey, the

observer, and the wireless operator/air gunner, Corporal T. S. Campion, to bail

out before the aircraft crashed near the bridge; all three survived to be taken

as prisoners of war.

Davy’s aircraft, ‘PH-G’, had also been hit, but his air

gunner, a 21-year-old Canadian, Aircraftman 1st Class Gordon Patterson, had

twice managed to hold off attacking enemy fighters to enable his pilot to

complete the attack. Then, having released its bomb load, the plane made a

steep climbing turn towards the covering cloud just as it came under further

attack from another 109 above. Patterson again held off the attacking fighter

and the 109 was last seen entering cloud and trailing smoke.

By now there was a long trail of smoke behind Davy’s

aircraft and both Patterson and the observer, Sergeant G. D. Mansell, reported

the port fuel tank to be on fire. They were just 3 miles north-east of

Maastricht as Davy gave the order to his two crew members to bail out. With his

crew gone, Davy then headed back towards Allied lines. The fire had seemingly

gone out and so he decided to remain at the controls. He could see that he was

desperately losing fuel but he managed to make it back across the lines and force-landed

just a few miles from his home base.

Although badly damaged, the aircraft was later taken to

Amifontaine and, as things turned out, would be the only Battle of the five to

have taken part in the raid to return. Davy would later be awarded the DFC for

his courage during the attack on the bridge at Vroenhoven and for getting his

aircraft back across friendly lines. His observer, Mansell, managed to evade

capture and made it back to Allied lines, but Patterson had suffered a broken

bone in his left foot and a broken arm, so he could not escape. He was

subsequently captured and treated in hospital in Liège. Gordon Patterson was

later awarded the DFM for holding off the marauding 109s long enough to enable

their attack on the bridge to take place; his award was the first Canadian DFM

of the Second World War.

The second section, led by Garland, had taken off from

Amifontaine just a few minutes after Thomas and Davy. The three Battles headed

off towards their target at low level beneath a layer of cloud. Garland’s

observer in ‘PH-K’, Sergeant Tom Gray, was one of seven brothers from Wiltshire

and just a few days away from his twenty-sixth birthday. He had joined the RAF

as an apprentice at the age of 15, and after leaving Halton had served as an

engine fitter before volunteering for flying duties; this was to be his first

bombing sortie of the war. Making up the crew was the wireless operator/air

gunner, Leading Aircraftman Lawrence Reynolds, from Guildford in Surrey, who

was just 20 years old.

Flying in Garland’s section were Pilot Officer I. A.

McIntosh in ‘PH-N’ and 28-year-old Sergeant Fred Marland in ‘PH-J’. By the time

they could all see the bridge at Veldwezelt, the three Battles had already been

spotted from the ground and a barrage of flak awaited them. Even before they

could start their bombing run, McIntosh’s aircraft had been hit in the main

fuel tank and had burst into flames. Quickly jettisoning his bombs, McIntosh

turned away and managed to make a forced landing near Neerharen to the

southeast of Genk in Belgium. He and his two crew members, Sergeant N. T. W.

Harper and Leading Aircraftman R. P. MacNaughton, were all captured.

Not wishing to hang around a moment longer than necessary,

the two remaining Battles quickly commenced their attack. Without flinching,

Garland and Marland flew head-on into the barrage of fire, seemingly ignoring

the flak that greeted them. Despite the intensity of the anti-aircraft fire,

Garland coolly led the two remaining Battles in a shallow dive-bombing attack

on the bridge. After releasing his bombs, Garland’s aircraft came under further

attack, this time from the enemy fighters. Looking across to where the other

Battle was making its attack, he witnessed Marland’s aircraft suddenly pitch

up, roll out of control and then dive into the ground near Veldwezelt; Marland,

his observer, 24-year-old Sergeant Ken Footner, and his wireless operator/air

gunner, 22-year-old Leading Aircraftman John Perrin, were all killed.

Garland’s bombs had hit the western end of the bridge, causing

it some notable damage, but he now found he was in the most hopeless of

situations. The Battle was no match for the 109s now swooping in numbers on

their helpless prey, and was promptly shot down. The aircraft came down in the

village of Lanaken, just 3 miles to the north of Veldwezelt; there were no

survivors.

Of the fifteen crew members of the five Battles that had

taken part in the raid, six were killed and seven were taken as prisoners of

war. Although it was such a tragic loss, it is fortunate that one of the

Hurricane pilots sent to sweep the area had witnessed the bravery of the Battle

crews over the bridges at Maastricht, and he would later report the outstanding

courage and determination displayed during the attacks despite such

overwhelming opposition.

In the London Gazette of 11 June 1940 it was announced that

Donald Garland and Thomas Gray were both to be posthumously awarded the

Victoria Cross; the first RAF VCs of the Second World War. Their citation

concluded:

Much of the success of this vital operation must be

attributed to the formation leader, Flying Officer Garland, and to the coolness

and resource of Sergeant Gray, who navigated Flying Officer Garland’s aircraft

under most difficult conditions in such a manner that the whole formation was

able successfully to attack the target in spite of subsequent heavy losses.

Nearly a year later, Garland’s mother attended the investiture ceremony at Buckingham Palace to receive the award to her son. She had four sons, but tragically they would all die while serving with the RAF during the Second World War.