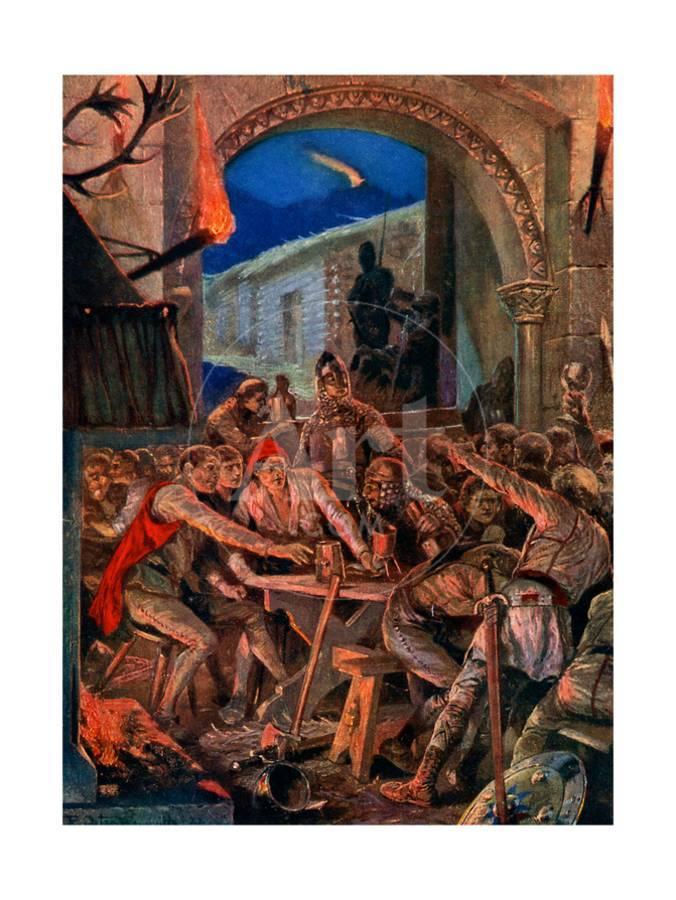

The Last Feast of Robert De Comines’ Men at Durham,

1069.

Preparing therefore a large fleet, he invaded England

with nine hundred ships, and in a severe pitched battle, Harold fell in fight, and

William the Conqueror obtained the kingdom.

Simeon of Durham, twelfth century

As darkness fell on late afternoon of 14 October 1066, the

‘fighting man of Wessex’ and his brothers lay dead and barely recognisable on

Senlac ridge. The demise of Harold Godwinson and his dynasty brought to a

premature end what may well have been a golden age of Anglo-Saxon rule in

England, but the survivors of Hastings had no time for the luxury of nostalgia

and were faced only with the bitter reality of death or submission. After the

battle, the victorious Duke of Normandy paused at his camp before beginning the

pacification of the south-eastern counties. Shocked and demoralised by the loss

of their formidable war leader King Harold, most of them surrendered without a

struggle, and on Christmas Day 1066 William was anointed as the monarch of all

England. A few months later, evidently satisfied with his progress, the new

king then returned for a short time to his ancestral lands in Normandy. But not

all of England was prepared to be subdued without further conflict and in the Conqueror’s

absence rose in revolt. Although this rebellion ultimately failed to pose a

united challenge to Norman rule, Northumbria played a large part in it and was

to pay an even larger price for its intransigence.

In the immediate aftermath of William’s accession, however,

life probably changed imperceptibly for the inhabitants of the North. After

their mauling at the Battle of Fulford in September 1066, Northumbria did not

contribute fighting men to the Anglo-Saxon levies at Hastings. Labourers

continued to toil in the rich pasture-lands around Durham, working busily in

the fields but bitterly mindful no doubt of the Scottish raiders who had burnt

their crops just a few decades earlier. Yet a chain of tragic events had begun

which brought into their midst Norman men-at-arms led by mail-clad knights on

their war horses.

Concerned predominantly with mopping up resistance in the

southern and western part of his new kingdom, William’s initial policy towards

the most northern counties was simply to sell off their potentially lucrative

control. But this proved at best to be unwise and at worst cynically callous as

distrusted outsiders became the new Earls of Northumbria. Even before the

Conquest, resentment was brewing in the North against what was regarded as unjust

taxation imposed on them by a distant Anglo-Saxon authority. Consequently, if

their strongly felt sense of custom and tradition was offended enough, the

insular Northumbrians were quite ready to unsheathe their weapons. Also, their

separate identity was strengthened by the growing prestige of the community of

St Cuthbert. After centuries of nomadic wanderings around the North, this band

of monks had settled at Durham from where miraculous fables of the northern

saint’s preserved body began to spread across the Christian world. Obviously

then, the appointment of a non-Northumbrian as Bishop of Durham in 1042,

followed by a succession of unpopular earls up to the eve of Conquest, had

caused further restlessness of which William either knew or cared nothing. It

was no surprise, therefore, when the identity of William’s first earl became

known, that Northumbria again slid down the precipice towards open rebellion.

William granted the earldom of Osulf to Copsi, who was on

the side of earl Tosti, … Osulf, driven by Copsi from the earldom, concealed

himself in the woods, in hunger and want, till at last having gathered some

associates whom the same need had brought together, he surrounded Copsi. Simeon

of Durham, twelfth century

In March 1067, Copsig, a Yorkshire noble, became Earl of

Northumbria. He followed in the footsteps of the reviled Tostig, who was

brother to King Harold but whose only success appears to have been to unite the

forces of resistance within Northumbria. From his power base in York, Tostig’s overbearing

stewardship had brought widespread revolt to the region. Incredibly, William

demonstrated utter indifference to this by later preferring Copsig, rather than

a Northumbrian rival, to become earl. Copsig had been deputy to the loathed

Tostig. There was barely time for an inaugural ceremony. Copsig’s only welcome

was the thrust of Northumbrian lance. After only weeks in power, Copsig

blundered into an ambush while ‘feasting’ at Newburn, about five miles west of

Newcastle, and desperately sought sanctuary in the nearby church. Although an

isolated riverside village, Newburn always had military significance for its

fords over the River Tyne. Roman troops are believed to have waded across here,

and fragments of stone in the riverside church of St Michael and All Angels may

date from that time. Its squat tower overlooking waterside meadows is

aggressively Norman, but tucked into its fabric are identifiable traces from

the Anglo-Saxon period.

So it is conceivable that a desperate Copsig may have fled

here, pursued by a phalanx of enraged and well-armed Northumbrians. At last

they had a symbol of their disaffection within striking distance and they did

not consider the implications of their actions. They ignored any plea for mercy

and set fire to the building, driving out the hapless earl, whose brief rule

ended in a hacking welter of sword and spear blades. While the exact details of

this assassination may have been conflated with a later murderous incident

where rough justice was similarly meted out to a despised figure of authority,

Copsig’s brutal removal from power clearly indicates the deeply felt grievance

of the people of Northumberland and Durham at a perilous moment in their

history.

But William’s grip on England was not yet strong enough to

retaliate immediately for the loss of Copsig. Not until 1069 did Durham at last

fall under the avenging shadow of the Conqueror. From his new castle at York he

ordered an expedition to silence the troublesome North forever.

In the third year of his reign, King William sent Earl

Robert, surname Cumin, to the Northumbrians on the north side of the Tyne. But

they all united in one feeling not to submit to a foreign lord. Simeon of

Durham, twelfth century

In the piercing cold of January 1069, a large detachment of

Norman knights and infantry approached the gates of Durham. Their cavalry

contingent may have numbered around seven hundred, one-third of William’s

estimated attacking force of knights at Hastings. Commanded by Robert de

Comines, a Norman Count who relished his promotion to earl, the taskforce had

contemptuously ignored a stark warning from Egelwin, Bishop of Durham, not to

enter the county. Undaunted and no doubt heartened by the ring of steel

surrounding him, Comines rode through Durham’s abandoned streets and

commandeered its rough collection of ill-assorted houses.

On a peninsula caught by a serpentine loop of the River

Wear, Durham provides a sublime position for defence. After crossing the river

and entering the town, the Norman column would slowly ascend a steep hillside

to the plateau on which a gleaming new cathedral had been built as a repository

for Cuthbert’s relics. It had been completed in 1017, and probably because of

the brilliance of its untarnished stonework, was known as the ‘White Church’.

Looking out from here, across the darkening valleys and moors, Comines must

have felt unassailable as his forces bedded down for the night. At dawn he

intended to strike out, perhaps using Durham as a command centre from which to

extinguish resistance in the surrounding region.

Even though thick woodland around the church and the

inhabited area had been partially cleared, enough remained to conceal all

movement in the surrounding valleys. Signals quickly passed around the area

calling together a grimly determined Northumbrian assault force. Their approach

muffled by the heavy foliage, they quietly assembled and waited to attack. Just

before dawn they darted forward, stealthily eliminating sentries and then

bursting into streets many of them would have known well. Even before a call to

arms could be given, Normans were struck down and the narrow lanes of Durham

echoed to the cries of sudden death.

The Norman military machine was a well-equipped, razor-edged

battering ram. Their cavalry capability was evolving to act most effectively in

open spaces where the speed and power of galloping attacks could pulverise

disorganised opponents into the earth. But when taken by surprise in the dark

and cramped environment of an early medieval township, the Norman knights and their

men-at-arms would hardly be able to lift their sword arms, let alone swing

their massive broadswords to any cutting effect.

The affair was conducted with great ferocity, the

soldiers being killed in the houses and the Streets. Simeon of Durham, twelfth

century

Norman soldiers probably died in confused, milling groups in

the lower part of the town, as with terrible efficiency the men of Northumbria

stabbed and slashed their way to the top of the hill and its command post where

Comines was desperately trying to rally his depleted troops. From the roof of

the headquarters, placed in ecclesiastical lodgings near the cathedral, a group

of surviving Norman spear and bow men desperately kept their besiegers at bay.

Raging flames ended their short-lived defence, however, and the building was

soon a blackened ruin containing the charred corpse of the Conqueror’s failed

lieutenant in the North.

Throughout the history of conflict, well-organised and

highly motivated combatants waging guerrilla warfare on their native soil have

inflicted humiliating defeats on an apparently superior enemy. Hardly

twenty-four hours after they had entered Durham, Comines’ spearhead force lay

dead on its streets. A lone survivor was permitted to struggle back with news

of this disaster which had engulfed the Norman army. They had obviously

underestimated the ferocity of the enemy ranged against them and were unable to

match the Northumbrian fighting men in close-quarter combat. Perhaps if the

unlucky King Harold had been able to employ similar tactics, the course of

English history would have been changed.

Instead, to strengthen his tightening grip on power, William

intensified his castle-building programme. Uncompromising fortresses soon

towered above town and countryside, constantly visible symbols of the

irrepressible Norman occupation. At Durham, in the wake of the Comines debacle,

work began on a timber motte which was quickly reinforced by stone. It was

raised on a mound opposite the cathedral, maintaining both a respectful

distance and a sense of superiority as it watched over Durham and the revered

sanctuary of Cuthbert.

Not surprisingly, the relative ease of the Northumbrian

victory emboldened resistance in the North. A firestorm of rebellion spread to

the garrison at York where its commander suffered a similar ghastly end as his

brother knight Comines.

William’s reaction was predictably harsh. He set in motion

the notorious ‘harrying of the North’, a scorched earth policy which at this

stage, because of further Danish incursions along the Ouse, was concentrated in

the Yorkshire area. Unrest in Cheshire also delayed retribution, and some

districts around the Tyne and to its north were consequently spared from the

most severe destruction.

The haste in which the castle was built sharply reflected

the parlous state of security in the region. William had persisted in

transferring authority to unpopular contenders who appeared able enough to calm

a belligerent Northumbria. But in May 1080, the weakness of this policy was again

made clear to him. On the banks of the River Tyne, with fire and the blood of a

bishop, the Northumbrians gave another scornful response to Norman rule:

Walcher, bishop of Durham, a native of Lorraine, was

slain, on Thursday, the second of the ides of May at a place called Goteshead

(that is the goat’s head) by the Northumbrians. Simeon of Durham, twelfth

century

It was no surprise that Walcher, the Bishop of Durham, was

unwelcome in his new community. After all, he had been appointed in 1071

following the ejection of the Northumbrian Ethelwine. Inflaming local

resentment further, the unfortunate Ethelwine was imprisoned by the Conqueror

and died in custody shortly afterwards. Subsequently, under a pall of gloom and

distrust, Walcher was enthroned as the first Norman Bishop of Durham and became

custodian of the new fortress which guarded the peninsula.

Walcher of Lorraine was not a close ally of King William,

but his ecclesiastical reputation was outstanding and he was equally renowned

for his dignity and political awareness. It seems certain that he made an

attempt to reconcile the men of Durham with their new masters but this was at

an inopportune time when the sore of dissent was too inflamed to heal. Indeed,

tension was only worsened by William’s momentous decision uniquely to combine

church and state within Durham by selling the earldom to Walcher. From humble origins

as a clerk in Lorraine, Walcher had risen to become Durham’s first Prince

Bishop.

The heady attractions of such high office may have robbed

Walcher of his former political astuteness. As earl he rekindled the blaze of

earlier unrest by imposing another deeply resented tax upon the region.

Similarly, he failed to prevent a further spate of Scottish raids deep into

Durham. But above all, in addition to this expanding catalogue of woes, he then

became fatally embroiled in the blood feuds of the Northumbrian aristocracy.

And so, 14 May 1080 became a day of nemesis for Walcher and the fractious

Northumbria he was struggling to control:

When the time came, they met at the appointed place; but

as the bishop would not hold the meeting in the open air he went with his

clergy and more worshipful knights into the church there. Simeon of Durham,

twelfth century

A truce was agreed and Walcher agreed to meet a Northumbrian

delegation on the Tyne riverside close to the settlement at Gateshead. It was a

surprising decision perhaps, given the bitterness between rival factions and

the proximity of the peace conference, in the rebel heartland, to the scene of

Earl Copsig’s slaughter thirteen years earlier. A small monastery at Gateshead

had overlooked the river crossing since the seventh century, and although the

exact site is now lost, it probably lay slightly east of the present church of

St Mary.

Walcher’s attempts at conciliation were ignored and on a

pre-determined battle cry, the angry Northumbrians drew their concealed weapons

and forced the bishop and his bodyguard back into the church. Wishing to

prevent further bloodshed he then bravely faced the levelled swords of his

antagonists. His reign, begun in hope and ended in acrimony, was over. So

virulent was the animosity against him and the regime he represented, that the

Northumbrian perpetrators of this atrocity were prepared to violate the

sanctity of a religious institution, an uncomfortable prospect in an age of strong

spiritual conformity. Shortly afterwards acrid smoke from the burning church

drifted over Walcher’s mutilated body.

Yet the spear-thrust which killed Walcher also dealt a

mortal blow to any lingering aspirations of Northumbrian freedom. On a bare

river mudbank known afterwards as ‘Lawless Close’, a party of monks discovered

the discarded corpse of their bishop. Even as they ferried him downriver for

burial, a Northumbrian assault battered against Durham Castle, now impregnable

on its rocky heights. There would be no repeat of the earlier Norman

catastrophe, however. Probably because they lacked the heavier equipment

necessary to break down a modern fortification, the siege failed and the

Northumbrians trudged back to their homes after four fruitless days. Never again

were they able to mount a concentrated onslaught against the Norman army of

occupation.

William’s rage would not be difficult to imagine. Any

possible inclination towards compassion had vanished in the flames of Walcher’s

funeral pyre. To weaken the potential Northumbrian threat he had already forced

a sullen oath of fealty from Malcolm III of Scotland. Now there could be no

interference as Northumberland and Durham stood alone and exposed, defying King

William to the last.

Yet on this occasion, the Conqueror did not cross the Tees

to personally chastise his obdurate Northumbrian subjects. Perhaps the legend

that he was overwhelmed by superstitious foreboding as he approached Durham

Cathedral during an earlier visit has some truth. Instead, Odo, Bishop of

Bayeux, who was more amply protected by the spiritual armour of his exalted

office, was despatched to wreak the monarch’s vengeance upon the North.

Odo was half-brother to William and rode towards the shield

wall at Hastings brandishing an iron war mace, but nothing is known of how well

he acquitted himself in the actual fray. But he was undoubtedly efficient in

his cruel suppression of the remaining resistance movement within Northumbria.

Given free reign he appears to have completed the ‘harrying’ with zeal. Simeon,

‘monk and precentor’, who is known to have been at Durham cathedral in 1104,

has described the effect of the whirlwind of devastation which engulfed

Northumberland and Durham during those desperate times. It is written with the

graphic outrage of a man who must have been an eyewitness to those traumatic

events.

It was horrific to behold human corpses decaying in the

houses, in the streets, and the roads, swarming with worms, while they were

consuming in corruption with an abominable stench. For no one was left to bury

them in earth, all being cut off by the sword or by famine. Meanwhile, the land

being thus deprived of any one to cultivate it for nine years, an extensive

solitude prevailed all around. There was no village inhabited between York and

Durham; they became lurking places to wild beasts and robbers, and were a great

dread to travellers. Simeon of Durham, twelfth century

It has even been suggested that significant members of the

region’s ruling class were summarily executed in a purge intended to end

Northumbria’s illusions of political separateness forever. Yet no matter how

savagely they were punished, the Northumbrians’ spirit of distinctiveness would

not be suppressed and proved its worth in the centuries of conflicts to come.