Background

The regular Ceylon Defence Force (CDF) was founded in 1910

although a reserve volunteer force had existed since 1881. The CDF came under

the command of the British Army. It was mainly British officered and the other

ranks were Ceylonese. An exception was the Ceylon Planters Rifle Corps, which

was made up of Europeans. This rifle corps took part in the South African war

of 1899 – 1902, as did the Ceylon Mounted Infantry. During the Great War many

Ceylonese of all races volunteered to join the British Army fighting in France.

Ceylonese units served in Egypt and in the Gallipoli campaign. During the

Second World War the regular units came under the control of Britain’s South East

Asia Command, headed by Lord Louis Mountbatten. The island was fortified

extensively in anticipation of a Japanese invasion. In April 1942, for example,

Japanese bombers, escorted by Zero fighters, mounted a large-scale surprise

attack on Colombo and on a nearby Royal Air Force base, knocking out eight

Hurricanes. Ceylon’s colonial forces deployed to occasional exotic garrison

duties in the Seychelles, and also in the Cocos islands (where it had to put

down a small Trotskyite mutiny among its own ranks; three soldiers were

court-martialled and hanged, making them the only ‘Commonwealth’ soldiers

executed by the British during the war). By 1945 the CDF numbered around

20,000.

After the war the CDF, in one case supported by British

Royal Marines, countered left-wing strikes. On independence, technically the

colonial force was disbanded but it was reconstituted into a new regular and

reserve force structure. The formal foundation of the post-independence army

dates from 9 October 1949 (now celebrated annually as army day; the navy and

air force celebrate different foundation days). In contrast with the rapid

mobilization of 1939 – 45, the CDF was reduced to around half its previous

size. A defence agreement of 1947 offered the new colony British protection in the

event it was attacked by a foreign state. British military advisers were

provided and in effect a British brigadier commanded the fledgling army.

Promising young Ceylonese officers were sent to the Royal Military Academy,

Sandhurst, and more senior officers were trained at the British Staff College

at Camberley. Some officers were sent to accompany the British Army of the

Rhine for cold weather, and Cold War, experience. The emphasis on foreign

military training was to continue as a hallmark of staff-officer education into

the twenty-first century, though Britain was to give way to the US, China,

India and Pakistan. Likewise, insignia, rank structure and officer ethos were

long influenced by the British Army, though the dictates of ethnic war

transformed some of the rules and standards taught at Sandhurst and Camberley.

Ironically, Sri Lanka much later offered to instruct NATO armies in

jungle-warfare skills.

Army

The Ceylonese army, now under an indigenous comma nder, led

its first major operation (Operation MONTY) to stop the influx of illegal South

Indian immigrants smuggled into the country. The army co-ordinated with what

was then the Royal Ceylon Navy. The army was busy in support of the police

throughout the 1950s during strikes and domestic riots. Trade union and

left-wing parties were active in much commercial disruption, most notably the

1961 Colombo port strike which caused major food shortages. Against this

background of left-wing agitation a number of officers planned the 1962 coup.

It was squashed just a few hours before it was due to be enacted. Fear of

military intervention undermined political confidence in the forces for

decades. The immediate result was the reduction of the military. In 1972 the

three main services were renamed to reflect the republican status. From 1983

the main focus of the army was COIN against the Tamil insurgencies, although

the two JVP Sinhalese insurrections (1971 and the late 1980s) also demanded

extensive military operations. Few armies have had to fight a series of civil

wars for over three decades. The ruling politicians were forced to learn to

love their armed services and pump men and money into them – just to survive.

Like many developing countries Sri Lanka contributed to UN

peacekeeping operations, in the early 1960s in the Congo and then, after 2004,

a series of missions in Haiti. The average Haitian deployment was around 1,000

personnel. In 2007 over 100 members of the mission, including three officers,

were accused of sexual misconduct including child abuse (though the latter

related to women under eighteen paid for sex). The UN investigation found all

the accused Sri Lankan military personnel guilty of the charges, although in

Colombo nationalist politicians talked of an international conspiracy, related

to criticisms from NGOs involved in the Tamil insurgency at home. Colombo

promised an official inquiry and prompt punishment while replacing the

offending regiment with 750 troops from the Gemunu Hewa Regiment. In 2010 – 11,

small deployments were also sent to Chad, the Central African Republic, Sudan,

and Western Sahara, while maintaining its major mission in Haiti. In November

2010 a mechanized infantry company (around 150 troops) was sent to join UN

forces in Lebanon.

Structure and size

The army’s organization is based on the British Army model.

And, like the Indian army, it has maintained in particular the regimental

system inherited at independence. The infantry battalion, the basic unit in

field operations, would typically include five companies of four platoons each.

Platoons usually had three squads (sections) of ten soldiers each. In 1986 a

new commando regiment was formed. Support for the infantry was standard –

armoured regiments, field artillery regiments, plus signals and engineering

support etc. In addition to commando forces, of interest were the special

forces and a rocket artillery regiment.

Official and unofficial Sri Lankan figures and ORBATs

(orders of battle) tend to differ from the standard Western data provided, for

example, by the International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS). The IISS

put the current strength of the army at 117,000 comprising 78,000 regulars and

39,000 recalled reservists. That is a big army for a small country (with a

population of just over 20 million), but not in the context of a long war. The

army was certainly much larger, however, during the intense fighting in 2006 –

09. Interviews with a range of officers at or above the rank of brigadier all

confirmed that the immediate post-war strength was around 230,000. Many senior

officers insisted that the army should not be reduced, despite the potential

post-war peace dividend, although they accepted, grudgingly, that natural

wastage would reduce their ranks. When the same officers were asked their

guesstimate of the size of the British Army, they all opined that it was much

larger than theirs. They were stunned to discover that it was just over 100,000

and being reduced to 80,000. They then stopped complaining about possible

reductions in the Sri Lankan army. The 1983 strength was roughly 12,000

regulars. Aggressive recruitment followed the outbreak of the Tamil war.

Today’s high figure of about 200,000 includes nearly 3,000

women. In 1979 the Army Women’s Corps was formed as an unarmed, non-combatant

support unit. Inspiration and early training came from the British Women’s

Royal Army Corps. Women in the British Army – except medical, dental and

veterinary officers and chaplains (who belonged to the same corps as the men)

and nurses (who were members of the Queen Alexandra’s Royal Army Nursing Corps)

– were in the WRAC from 1949 to 1992. Initially the Sri Lankan equivalent was

similar to its British parent. Enlistment involved a five-year service

commitment, (the same as men) and recruits were not allowed to marry in this

period. They did basic training and drill, but not weapons and battle training.

Females, however, were paid at the same level as the men, but were generally

limited to communications, clerical and nursing duties. The long war prompted

the expansion of the Women’s Corps; two women reached the rank of major

general. By 2011 the Women’s Corps comprised one regular and four volunteer

regiments.

Since Sri Lanka forces were all-volunteer – that is, there

had been no conscription – all personnel had volunteered for regular or reserve

service. Conscription had been regularly debated and since the 1985 legislation

the government has had the legal power to enforce national military service.

Economic pressures, patriotism, religious nationalism and local, familial or

caste traditions had managed to fill the ranks, however. Recruitment was in

theory nationwide, though this did not apply in the northern and eastern

provinces during the war (some Tamils, however, joined pro-government militias

as well as the regular forces). After the war, plans were announced to form a

‘Tamil regiment’ to promote integration in the army. (Another exception was the

Rifle Corps which recruited from a specific area.)

The Sri Lanka Army Volunteer Force (SLAVF) was the main

volunteer reserve of the army. It was the collective name for the reserve units

as well as the National Guard. The SLAVF was made up of part-time officers and

soldiers, who were paid the same as the regular forces when on active duty.

This was in contrast to the Regular Army Reserve, which comprised people who

had a mobilization obligation for a number of years after their former

full-time service in the regular army had been completed.

Operational command varied according to the tempo of the

COIN war. The Army General Staff had been based at the Army HQ. Troops were

deployed to protect the capital – which suffered a series of major terrorist

attacks. Troops to defend the capital were based at Panagoda cantonment, the

headquarters of a number of regiments, as well as a major arsenal and military

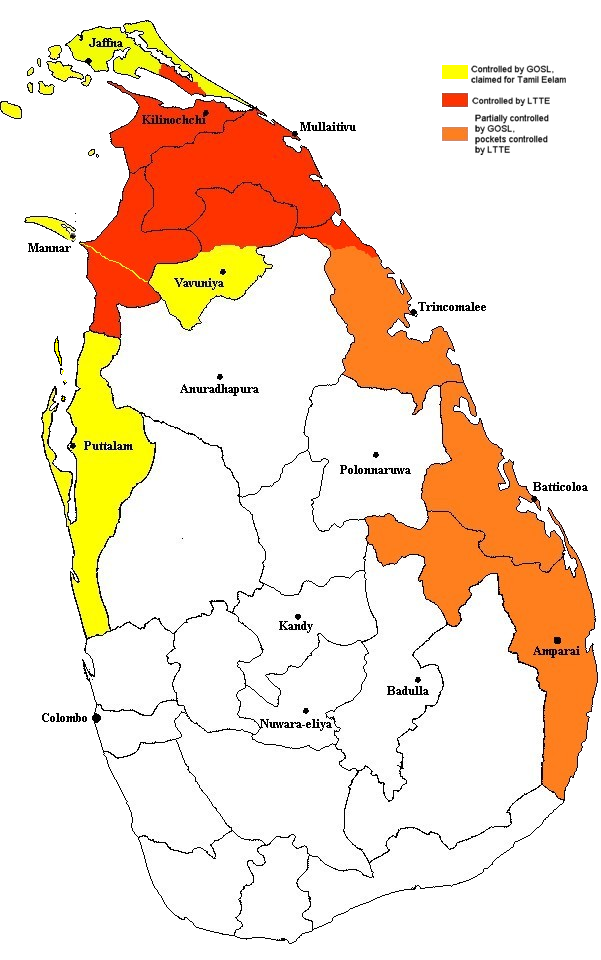

hospital. The majority of infantry troops were deployed into the northern and

eastern provinces during the war; they were placed under six commands known as

Security Forces Headquarters: in Jaffna (SFHQ-J); Wanni (SFHQ-W); East (SFHQ-E),

Kilinochchi (SFHQ-KLN); Mullaitivu (SFHQ-MLT) and South (SFHQ-S).

For officer training Sri Lanka largely adopted the British

model. The local equivalent of Sandhurst was the Sri Lanka Military Academy

(SLMA) based in Diyatalawa, where the young officer cadets trained for ninety

weeks, much longer than their UK equivalents. Following the British model (set

up in the UK in 1997) middle-ranking officers from all three services were

educated at the Defence Services Command and Staff College. Just outside

Colombo, the Kotelawala Defence University was established in 1981, as a

tri-service college for young cadets (aged eighteen to twenty-two) to pursue a

three-year course. Foreign senior-officer training migrated from the UK to more

friendly, or generous, allies in Pakistan, China, Malaysia, the US and more

recently the Philippines. More covert was the COIN training received from the

Israelis, who have had a close intelligence and procurement relationship with

Sri Lanka since the mid-1980s. In the early period the Israelis assisted with

instruction in FIBUA (Fighting In Built-Up Areas).

Army’s weapons

The army’s equipment was initially British Second World War

surplus, although some post-war armoured fighting vehicles such as the

Saladins, Saracens and Ferrets were also added to the inventory. By the 1970s

the USSR, Yugoslavia and China had displaced Britain; Chinese support was the

most consistent. Modern counter-insurgency demanded modern military hardware,

including heavy machine guns, rocket-propelled grenade launchers, 106mm

recoilless rifles and 60mm and 81mm mortars as well as up-to-date sniper rifles

and night-vision equipment. Armoured mobility was also needed. The old Saladins

and Ferrets and the like were too vulnerable to anti-tank weapons let alone

mines. China provided an array of tracked and wheeled armoured personnel

carriers (APCs) including the Type 85 amphibious variant. From Moscow came

forty-five of the BTR-80 APCs to replace the trusty old BTR-152s. After 1985

South Africa provided Buffels which had proved very effective in apartheid’s

bush wars, especially against land mines. Sri Lanka then developed its own

variants, the Unibuffel (300 were locally manufactured) and the Unicorn. The

Soviet Union provided nearly 300 infantry fighting vehicles (variants of the

BMP). The Czechs shipped in around eighty T-55 medium battle tanks, while China

matched the supply of tanks (Type 59s). The army also used Chinese Type 63

amphibious tanks. Sri Lanka claimed it had sixty-two MTBs (Main Battle Tanks).

Much of the imported kit was obsolete or obsolescent, but it was refitted and

often proved useful in combat.

Artillery came largely from China, especially 122mm, 130mm

and 152mm howitzers introduced from the mid-1990s. From 2000 the deadly

offspring of the ‘Stalin Organs’, 122mm multi-barrel rocket launchers, were

deployed. Colombo acquired around thirty RM-71s from Czechoslovakia and a

handful of BM-21s from Russia. Rocket artillery may not be very accurate but it

can have a devastating effect, physically and morally, at the receiving end.

The army was also well equipped with the standard array of mortars, from 60mm

light mortars to 120mm towed versions — all courtesy of Beijing. It also used

fairly sophisticated radar counter-battery equipment, the US-designed AN/TPQ-36

Firefinder at first. But the American system was old and the Sri Lankans had

problems with spare parts. Then the Chinese stepped in with better equipment.

When I asked the army commander, Lieutenant General Jagath Jayasuriya, what he

regarded as his most useful bit of kit, he did not hesitate: ‘Artillery

locating radars. We could locate friend and foe. That was the most important.

We had five of them [systems]. With interlocking systems, we had total

coverage. From 2008, it was in position. ’ Most of the army casualties had been

from LTTE mortars and artillery.

A senior artillery expert in the army, Brigadier A. P. C.

Napagoda, summarized the 2006 – 09 campaign thus:

From the battle of Marvil Aru to the final battle at the

Nandikadal lagoon the artillery brigade employed a sufficient number of light

field medium guns, MBRL [multi-barrel rocket launchers] and locative radars …

which facilitated the creation of high gun density over any given area.

The Sri Lankans patched together local and imported signals

systems. Perhaps the most important was the provision of live feeds from

unmanned drones to the army HQ and divisional HQs. The other primary means of

communication were radio and CDMA (code division multiple access technology);

the latter allowed commanders at all levels secure and interactive full

‘duplex’ communication. VHF and UHF jammers were deployed to disrupt enemy

networks. The army also used locally manufactured manpack bomb jammers to

nullify LTTE improvised explosive devices.

Sri Lanka acquired a wide range of infantry weapons. The

Beretta M9s and Glock 17s were frequently used handguns. The communist-sourced

AK-47 assault rifles were very common, and, from the West, Heckler and Koch

G3s, FNs and American M16s. Machine guns were varied too: ranging from the

classic British Sterling to German MP5s and also Israeli Uzis. The vintage FN

MAG gun was a traditional and reliable workhorse. The Chinese versions of the

Russian RPD (Type 56 LMG) were also in evidence. Grenade launchers arrived from

South Africa and Germany as well as the M-203 from the US. Many of the RPGs

(man-portable rocket launchers) came from China and anti-tank missiles were

sourced from Pakistan.

Army tactics

On land and sea the government forces fought conventional

war unconventionally, sometimes aping and mastering the asymmetric tactics of

the insurgents. Above all they used small-group long-range tactics by special

forces to destabilize the enemy rear. The Commando regiments were set up in

1980, but the most effective troops were the special forces (SF) set up in

1985.

The special forces comprised around 5,000 troops in five

regiments. They trained originally with the Israelis, mainly in urban warfare,

but soon the Sri Lankan SF became arguably the best jungle fighters in the

world. They fought in eight-man teams, although sometimes two teams of eight

would combine, especially in an emergency or for logistical purposes. For

example, one surveillance team might overlap with a team establishing a forward-supply

cache (usually of ammunition, water and medicine) and then join forces if they

met hostile elements. The SF did not use helicopters for insertions, partly

because of the jungle terrain and partly because of stealth. They would walk in

and often penetrate up to forty to fifty kilometres behind the lines. The air

force was used only five times in emergency casevacs, usually by Mi-24

choppers. Nor did the SBS or navy work directly with the army SF. The SF

commander told me: ‘We did no landings by sea – ground penetration was safer

for us.’ Paradrops were not considered, not least because of the Indian army

debacle in Jaffna.

The long-range patrols (LRPs) could last up to a month. They

would act as spotters for air and artillery strikes. They would also disrupt

LTTE movement not least by targeting their leaders and communications. The SF

were also used defensively to plug successful LTTE counter-attacks or to

staunch the occasional LTTE spectacular. For example, on 29 September 2008, the

LTTE elite Black Tigers hit an air force base in the rear of army operations.

Two Tiger aircraft also bombed the base. SF squadrons were rushed in to halt

further LTTE exploitation of the surprise attack.

Interestingly, the special forces did not utilize captured

insurgents, partly because many Tigers took suicide pills rather than

surrender. Even when they were captured, the SF were extremely reluctant to

accept any ‘turned’ insurgents. Despite the widespread and effective use of

so-called ‘turned terrorists’ in the Rhodesian Selous Scouts, itself based upon

British ‘pseudo-gang’ techniques applied in Malaya and Kenya, the Sri Lankan SF

deployed only a handful of Tamil-speaking former Tigers and then very

reluctantly and very occasionally. According to SF sources, there was only one

example of a pseudo using his insurgent knowledge and the Tamil language to

enable SF troops to disengage from a position where they were vastly

outnumbered.

The army’s massive recruitment drive – attracting

3,000-5,000 men per month in the last two years of the war – allowed for attack

and defence in depth. Combined services provided two or three infantry lines to

prevent the previous LTTE tactic of outflanking or penetrating the lines, and

then attacking from the rear. This would imply an unimaginative linear type of

mentality. In fact, the ethos of the SF and commando long-range patrols were

applied throughout the infantry in the focus on small-unit initiative. Special

Infantry Operations Training (SIOT) – the initial courses were forty-four days

– allowed the small units to carry out complex operations in often difficult

terrain. The insurgents knew their own territory and so the army sought

infantrymen who had been born and bred in the villages and who might also

possess the same familiarity with jungles and endurance as the guerrillas they

encountered. The small group approach from the SF down to the ordinary infantry

created flexibility and often area dominance. Ability, not least from NCOs, was

rewarded; promotion of good NCOs to officers was also encouraged. Mission

command was to be seen at most levels, certainly best practice in COIN.

A close observer of the war, Dr David Kilcullen, an

acknowledged authority on COIN, commented on the final stages:

The Tigers chose to confront the government in a

symmetrical way, in terms of open warfare. In response, the Sri Lankan army

destroyed them with a combination of conventional and counter-guerrilla tactics

that denied the Tigers a comparative advantage while the tempo of operations

prevented the Tigers from regrouping.

The basic approach of the LTTE was to combine guerrilla

warfare, positional defence and IEDs to slow down and inflict heavy casualties

by indirect fire – artillery and mortars. The LTTE erected numerous ditches and

bunds which were often heavily, and randomly, mined. Army sappers had to devise

all sort of means of dealing with these fortifications, including the use of

improvised Bangalore ‘torpedoes’. An independent bridging squadron was also

formed as part of the combat engineering effort. On a smaller scale, the

infantry used spring-loaded ladders to deal with bunds. Engineers modified

tractors to compensate for the lack of roads, especially during heavy monsoons

and flooding. Often rations had to be airdropped. The much larger army required

a massive logistical back-up.

One engineering challenge was met by installing steel mesh

in the Iranamadu and Udayar Kattu reservoirs to protect against underwater

Tiger infiltrators. Water was also a challenge for the Army Medical Corps. Near

drowning, an unexpected type of casualty, was encountered when the LTTE blasted

the bund around the Kalmadukulam Tank (reservoir). Frontline medics had to deal

with 60 per cent of casualties from mortar and artillery blasts and 40 per cent

from gunshot wounds. They also had to treat tropical diseases, especially

Hepatitis A. Post-traumatic stress disorders also took their toll.

In short, tactical flexibility plus the massive numerical

superiority (as well as air supremacy) allowed the army to dominate and then

overwhelm the Tigers towards the end of the campaign.

The Navy

As befits an island in the middle of crucial sea lanes,

naval defence has always been a major security issue. In 1937 the Ceylon Naval

Volunteer Force (CNVF) was set up. The Second World War meant a rapid

absorption into the Royal Navy. In 1950 a small nucleus of officers and men

forged the Royal Ceylon Navy, to change its name, as with the other services,

when the country became a republic. Initial naval expansion depended upon

purchase of ex-British and Canadian ships. The navy suffered perhaps even more

than the army from the fallout from the 1962 coup conspiracy. Ships were sold

off and manpower reduced, as was training in the UK. The navy was therefore

ill-prepared for the first JVP insurrection and the beginning of the Tamil

revolt. The immediate stopgap was the gift of initially one of the more

advanced Shershen-class torpedo boats from the USSR and purchase of the

unsophisticated Chinese Shanghai-11-class fast gunboats for coastal patrols and

port protection. New bases were built primarily to interdict smuggling

operations from southern India. The navy also developed a land component for

base defence, becoming known later as Naval Patrolmen and capable of offensive

operations. The navy also replicated the British SBS – the Special Boat

Service. As the LTTE war expanded – and the Tigers relied on extensive overseas

procurement – Sri Lanka developed a blue-water strategy capable of sinking

large ships, even just outside the territorial waters of Australia.

The naval HQ was based in Colombo; this controlled six naval

command areas. After the war some of the coastal defence was transferred to a

newly formed Coast Guard.

The 2012 fleet consisted of over fifty combat, support ships

and inshore craft, sourced from China, India, Israel and, more recently, from

indigenous build.

The IISS put the size of the navy as 9,000 personnel, both

active and reserve, but this appeared to be an underestimate. Probably the more

accurate figure was 48,000, of whom approximately 15,000 were dedicated to land

deployment. Women served in regular and reserve roles. Initially women were

limited to the medical branch but the tempo of war led to females serving in

all branches. A female doctor reached the rank of commodore in 2007.

The navy’s weapons

The navy boasted about 150 vessels, but the core consisted

of around fifty combat and support ships. In addition, the navy rapidly

manufactured 200 small inshore patrol craft. The majority of the larger vessels

came from China, India and Israel, though the Sri Lankans began building their

own bigger ships. The largest warships were five offshore patrol vessels, with

the SLNS Jayasagara built in Sri Lanka (and commissioned in 1983). All the

blue-water vessels could operate naval helicopters (but insufficient funding

and air force opposition prevented any such deployment). The offshore patrol

ships played a vital role in interdicting and finally sinking the major Tiger

supply and storage ships. In 2001 two Israeli Saar 4-class fast missile boats

were procured. Dubbed the Nandimithra class by the Sri Lankan Navy (SLN), they

carried Gabriel 11 anti-ship missiles as well as a range of guns which

augmented the conventional warfighting capability.

The workhorse of the navy – involved in regular coastal

combat – was the fast attack flotilla. It was formed in the early 1980s with

Israeli Dvora-class boats to counter LTTE gun-running in the Palk Strait

between India and Sri Lanka. Two Dvoras were purchased in 1984 and another four

in 1986. Around twenty-five metres long, and displacing about forty-seven tons,

able to reach 45 knots and bristling with rapid-fire guns, they were able to

deter the ‘swarming’ wolf-pack tactics of the Sea Tigers – a major element in

asymmetric naval warfare. Small fibreglass Sea Tiger suicide craft would attack

naval and civilian convoys. The fast-attack flotilla also patrolled the many

creeks and landing points in LTTE territory to disrupt smaller boats securing

resupply from the larger blue-water Tiger ships. The flotilla was made up of a

variety of fast-attack craft types: four heavier Israeli Super Dvora (Mark 11)

were delivered in 1995 – 96. The navy also used the Israeli Shaldag-class

design to construct its own Colombo class. Ten other fast-attack craft originated

in China.

Compared with their counterparts in other navies, the SLN

fast-attack craft were much more heavily armed. They started with two or three

machine guns but became more heavily armed to counter the arsenals fitted on

Sea Tiger craft. Eventually, the fast attack craft had Typhoon 25 – 30mm

stabilized cannon as the main armament. They were connected to day-and-night,

all-weather, long-range electro-optic systems. The recent Colombo class was

equipped with an Elop MSIS optronic director and the Typhoon GFCS boasted its

own weapons control system. They also sported fancy surface search radar

systems. In addition they carried weapons such as the Oerlikon 20mm cannon,

automatic grenade launchers and PKM general purpose machine guns. This sounds

over-armed but heavy firepower was required to protect the crews from suicide

Sea Tigers trying to ram them or explode themselves close by. The fast-attack

craft typically had eighteen crew members and operated in group patrols,

usually, but not always, at night. The Tigers fought very hard and would not

retreat; occasionally the flotilla had to withdraw from engagements. A

fast-attack captain said, ‘Flak jackets were no good, except for bits of

shrapnel; the heavy calibre [Tiger] guns would tear people in half.’

Inshore patrol craft were much smaller (fourteen metres

long). They were used for harbour defence and amphibious operations. In

addition, the seven-metre-long Arrow class were heavily armed speedboats

manufactured in Sri Lanka and used by the SBS and its variant, the Rapid Action

Boat Squadron (RABS). The SBS, formed in 2005, comprised around 600 men. Those

who passed the tough training for the SBS but who were not good enough for the

final selection phase could join the RABS, which numbered around 400 men.

To support larger amphibious operations the SLN had a tank

landing ship and other utility craft. The Yuhai-class ship could transport two

tanks and 250 troops. There were also smaller Chinese-made landing craft. The

SLN had several auxiliary vessels for personnel transport and replenishment.

During the war the navy had no dedicated air assets or UAVs.

Afterwards, the embryonic fleet air arm based on the offshore patrol ships

started experimenting with HAL Chetak (the Indian revamp of the venerable French

Alouette III) and HH-65 Dolphin choppers, used extensively by the US Coast

Guard in short range air-sea rescue roles.

Most of the naval assets and SBS units were based during the

war at Trincomalee, one of the best and most attractive harbours in the world.

It was attacked consistently during the war, from and under the sea, and from

cadres who had infiltrated the nearby wooded hinterland. Any British visitor to

the base would be struck by its colonial heritage: the streets and junctions

are named after Oxford Street and Piccadilly Circus. Monkeys clamber over

verandahs of Seymour Cottage in Drummond Hill Road. It is very orderly, very

Royal Navy, including the smart waiters in the mess/wardroom serving up a

perfectly chilled gin and tonic in the sticky heat.

Maritime tactics

It is very rare for an insurgency’s naval forces to reach

parity and even on occasions outmatch the conventional COIN power’s force. The

naval war was long, active and intense: it involved the biggest tonnage of

ships sunk since the Falklands war of 1982. To defend the 679 nautical miles of

coastline the navy grew to nearly 50,000 (including 15,000 Naval Patrolmen for

land-based security), almost the same size as the Indian navy. But for most of

the war the Sea Tigers proved more flexible and destructive especially with

their swarming tactics mixing suicide and attack boats. They sank a Dvora fast

attack craft in August 1995 and another in March 1996. The Tigers filmed their

sea victories for their propaganda outlets. They destroyed a further six of

other classes of fast attack craft. After the ceasefire ended in 2005, the Sea

Tigers sent out larger and more craft, mixing suicide craft among the wolf

pack. The Black Tiger suicide crews and boats were difficult to detect, with

their low profiles and 35 – 40 knot speed.

Just as the army developed the small-group concept, the navy

advanced its own small boat variant. They tried to ‘out guerrilla’ the

guerrillas. The navy copied the Sea Tigers’ asymmetric swarm but on a much

larger scale. Hundreds of small inshore patrol craft were built from

fibreglass; the smallest was the twenty-three-foot Arrow. Large fourteen-metre

and seventeen-metre variants were also built. The larger boats had

double-barrelled 23mm guns and a 44mm automatic grenade launcher (the latter

acquired from Singapore). The fast-attack craft had more endurance, reach and

firepower, but they were unstable in heavy seas and often needed to be

augmented by the small boats to defeat swarms. The inshore patrol craft (IPCs)

were based in strategically important locations ready for rapid-reaction forays

against surprise assaults by the Sea Tigers. Although much of the fighting was

at night, the navy had to maintain twenty-four-hour surveillance. Several

squadrons could unite to form an anti-swarm of sometimes up to fifty or sixty

boats. Echoing infantry tactics on land, they used an arrowhead formation to

expand the arc of fire. Or they would attack in three adjacent columns in

single file to mask their numbers and increase the element of surprise.

The SBS operated in four- or eight-man teams, deploying in

Arrow boats or rubber inflatable boats for covert insertions. The SBS provided

vital surveillance but also took part in land-strike missions. SBS basic

training was for one year, with the majority dropping out before the end. Their

training was said to be augmented by Indian Marine Commandos, as well as US

special forces, including SEALs. The RABS manned the large number of

anti-swarming boats, a tough and dangerous role.

The navy’s lacklustre performance was much improved after

2006. It contributed immensely to the government’s war effort by coastal

interdiction of arms supplies to the Tigers, then it went further by adopting

an extended blue-water strategy by sinking eight ‘Pigeon’ ships, the LTTE

floating warehouses. Crucially, it also provided the umbilical supply line to

the garrison in Jaffna. Towards the end of the war it prevented escape by sea

of the surviving Tiger leadership, as well as engaging in humanitarian missions

for civilians fleeing the fighting.

The keys to LTTE logistics were the unflagged merchant ships

which would loiter 1,600 kilometres from the island, and then advance to 150 or

so kilometres off the coast to liaise with LTTE fishing trawlers, escorted by armed

Sea Tiger boats. The navy initially attacked the logistic trawler fleet,

sinking eleven in the first year of renewed fighting. With the help of Indian

and, sometimes, US intelligence, the navy sought out the LTTE Pigeon ships. The

navy deployed its most up-to-date offshore patrol vessels, the Sayura

(ex-Indian navy, re-commissioned in 2000) and Samudura (formerly the USS

Courageous, transferred from the US Coast Guard in 2004); it quickly converted

old merchant ships and rust-bucket tankers as replenishment vessels. The

long-range fleet sank the first floating warehouse on 17 September 2006, 1,350

nautical miles from Sri Lanka. A further three were sunk in early 2007. Then

audaciously the navy extended itself 1,620 nautical miles southeast, close to the

Australian territory of the Cocos Islands off the coast of Indonesia, to

destroy three ships in September 2007 and a fourth in early October.

Vice Admiral D. W. A. S. Dissanaayake, the naval commander,

was sitting in his splendid office in Naval HQ in Colombo, with a fine view of

the sea and the lighthouse built by the British. He was a poet and songwriter

in his spare time. ‘We are not a big navy – we don’t have frigates. We

improvised,’ he said. ‘But we went nearly all the way to Australian waters and

sank the last four vessels.’

The Pigeon ships did not possess heavy-calibre weapons but

they would open up with machine guns, mortars and RPGs when challenged by the

navy. The Vice Admiral explained how – after initial resistance – the LTTE

seamen did not offer to surrender. They either swallowed their cyanide tablets

or simply drowned. On both sides in the naval war, there were few stories of

capture at sea or rescue of survivors. Little or no quarter was given in

littoral or deepwater combat. Because the LTTE vessels were rogue ships, naval

officers claimed the right to protect themselves when they came under attack

from the Pigeons. The loss of their supplies of weapons, ammunition and

medicines was a major logistical defeat for the Tigers.

The Vice Admiral was equally voluble about the navy’s

logistical achievements, especially the supply to Jaffna. The city was an icon

to both sides in the war. The Tigers occupied it in 1986 and the Indian forces

managed to briefly and precariously occupy it in 1987; it returned to rebel

control from 1989 to 1995. The army regained the city in 1995. Thereafter its

long siege was as symbolic to the Colombo government as Leningrad (now St

Petersburg) was to the Soviets in the Second World War. It had to be held at

all costs.

The navy escorted a converted cruise ship they dubbed the

Jetliner to resupply the city. It took five to six hours to pass LTTE

controlled coastline on the dangerous journey from Trincomalee up the northeast

coast to Jaffna. The western route is not navigable, except by very small boats

or hovercraft. The Jetliner, heavily armed itself with machine guns, was

typically escorted by over twenty ships and boats, to deter Sea Tiger raids.

Beechcraft aircraft and UAVs tracked the convoy. It left early in the morning

and, once in Jaffna, had to organize a very quick turnaround, thirty minutes,

so as to traverse the LTTE coast before dark on the return journey. Over forty

tons of cargo and approximately 3,000 troops were transported once or twice a

week. The whole of the navy and indeed most of the top brass in defence HQ

would be on alert until the convoy sneaked past the dangers of LTTE artillery

and sea attack. Jaffna was also supplied by air but only the navy could provide

the heavy lift of sufficient men and equipment to keep the city in government

hands.

‘If the ship had gone down, we would have lost the war,’ the

navy commander admitted.

The navy was also proud of its actions during the final

phases of the war. The Vice Admiral insisted the navy did not use any naval

gunnery to attack the LTTE remnants in the Cage, but it did take extensive

risks from last-ditch suicide boats to rescue thousands of civilians from the

beaches as they tried to flee Tiger punishment squads and the Sri Lankan army

envelopment.

The navy endured heavy fighting — some sea battles lasted

fourteen hours — and many early reverses in ships sunk. The navy leadership was

also targeted by Black Tiger squads. On 16 November 1992 the head of the navy,

Vice Admiral W. W. E. C. Fernando, was killed in Colombo by a suicide bomber on

a motorcycle who drove into the Admiral’s staff car. In October 2007 a truck

bomber killed an assembly of 107 off-duty sailors, one of the most deadly

suicide attacks of the war. In all, the navy lost over a thousand of its

personnel in the conflict. Nevertheless, it finally achieved sea dominance

because of its small-boat concept in defeating the Sea Tiger swarms, and the

major interdiction of LTTE supplies. It was a four-dimensional war – a land,

air and sea and underwater fight. The navy did not develop a sophisticated

anti-mine warfare capability, however. The Tigers used frogmen with mines and

semi-submersibles to destroy navy ships. The Tigers were trying to develop

submarine warfare; various crude prototypes were captured by the army in the

last stages of the war.