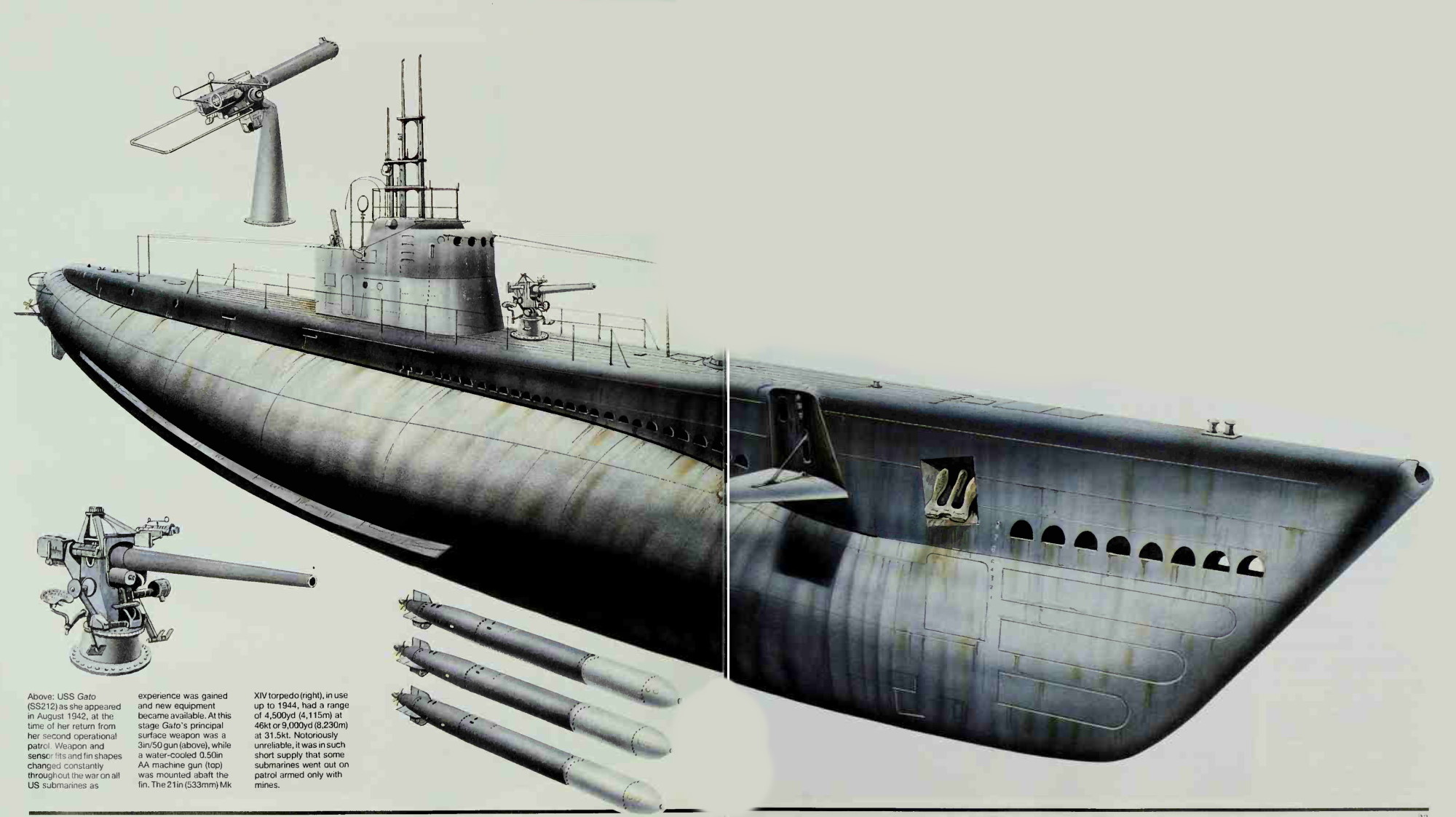

USS Perch (SS 313) of the Balao class. The Balaos were

virtually identical to the Gatos, but design changes to facilitate rapid

building resulted in greater structural strength and an increase in diving

depth from 300ft (91m) to 400ft (122m). This photograph shows clearly the many

protrusions on a typical World War II submarine. As well as creating

considerable under- water drag, leading to low speed and limited endurance,

they were a source of considerable noise, making them readily detectable.

Geography dictates that virtually all US Navy warships must

operate at considerable distances from the continental USA. Apart from purely

coastal vessels, therefore, the majority of its warships, and particularly the

submarines, need long range and a good cruising speed to reach their operational

areas in a reasonable time. During World War I the enemy was Imperial Germany

and Japan was an ally, but the possibility of a confrontation with the ever

more powerful Japanese was increasingly important to US Navy planners from the

early 1920s onwards. The ranges of operations involved in such a conflict were

beyond anything then being considered by other leading navies, and in the major

strategic plan – Plan Orange – it was expected that the principal operational

base in a war against Japan would be the US west coast, the Philippines and the

mid-Pacific islands being presumed lost in the early stages.

Design

The US Navy had long followed a policy of gradual

improvement, producing submarines which without excelling in any single aspect

of their performance were, nevertheless, extremely reliable, with long range,

good habitability and large numbers of reload torpedoes, all essential

attributes in boats operating for protracted periods at great distances from

base. Particular emphasis was placed on propulsion, and the US Navy was so

determined to have a guaranteed source of really reliable and economical diesel

engines that it even assisted in the dieselisalion of the US railroads, a

policy which resulted in the perfection of four types of high-speed diesel. In

addition, it had also experimented in the inter-war years with a composite

drive on the S class and direct drive on the Ts and Gs. but for the Gato class

it returned to the proven diesel-electric drive.

There had been constant debate in the US Navy about the gun

armament for submarines, and so strongly did the naval staff feel about

preventing submarine captains from becoming involved in surface actions that

they deliberately restricted the armament to one Mk 21 Mod 1 3in/50

anti-aircraft gun. This weapon’s inadequacy was proved beyond doubt in the

early war years, and US submarines underwent constant up-gunning throughout the

war. as did those of most other navies, until the revolution in submarine

design led to the elimination of all gun armament. There placement for the 3in/50

on the Gato class was the Mk 17 5in/25 a ‘wet’ gun produced from non-corrosive

materials, which enabled the muzzle and breech covers to be eliminated. In

design terms the Gato class was a progressive development of the Porpoise

class, and the Gatos’ high surface speed of just over 20 knots proved

invaluable in reaching patrol areas and achieving good firing positions for torpedoes.

The all-welded construction facilitated production, which

was confined to four yards, the most unusual being that at Manitowoc on Lake

Michigan, some 1,000 miles (1,610km) inland. Not only did the boats have to be

launched side! ways into the river, but they then had to travel down the

Mississippi to reach the sea.

This highly successful class show the soundness of the

American policy of developing reliable hull and engine designs over a long

period. The US Navy’s task was. however, somewhat simplified by having no real

requirement for smaller, more manoeuvrable and shorter ranged submarines.

During World War II US submarines, normally operating at considerable

distances from their bases, sank over nine-tenths of Japan’s major vessels, an

achievement in which code-breaking played a considerable part, but to which

successful submarine design also contributed. Most of the later fighting was

done by the 73-strong Gato class, and by the 132 Balaos and 31 Tenches that

were developed from them. Eighteen of the Gato class were sunk by enemy action

and one was a constructive total loss.

The Gato class is one of those which bridged the gap between

the last of the submersibles and the first of the true submarines. In its

original form the Gato epitomised the US Navy’s long-range attack submarine and

operated with great success and distinction against the Japanese, and with the

other similar classes, the Gatos played a significant part in bringing Imperial

Japan to the verge of surrender by devastating its merchant fleet. However, the

Gato class boats were slow under water: their maximum submerged speed was 8.75

knots, and even this could not be sustained for any great period without

draining the batteries. Also, as with virtually all their contemporaries, the

designed operating depth of 300ft (91m) was a trifle less than the overall

length of 311.75ft (95.2m), which imposed considerable constraints on

manoeuvrability.

The next class of US submarine – the 132-strong Balao class

– was virtually identical with the Gato, but had a strengthened hull, enabling

the members of the class to dive to 400ft (122m), and earning them the name

‘thick-skinned Gatos’. The Tench class was also based on the Gato, but only 31

had been built when the war ended and production ceased.

Electronics

The Gato class boats were among the first to have a

comprehensive electronics fit, eventually comprising a full range of radar,

sonar, communications and electronic warfare equipment. The actual fit was in a

constant state of change as new equipment became available and as boats could

be spared to have it installed, and masts and antennas proliferated with little

effort at reducing drag until by the war’s end there was a veritable forest

atop every submarine’s fin.

The first air search radar small enough to install in a

submarine, the SD, became available at the end of 1941, and its small bar

antenna was usually mounted at the head of the HF communications rod antenna.

The SD gave no directional information, had a maximum range of only 10 miles (16km)

and was easily detected by enemy RDF; nevertheless, it met the submariners’

urgent need for early warning of the approach of an aircraft, and by mid-1942

all US submarines were fitted with SD, while the SJ, which gave both range and

bearing, was starting to enter service. Although difficult to calibrate and

somewhat unreliable, the SJ gave submariners a totally new capability, and when

the circular plan position indicator display replaced the earlier horizontal

line display great confidence was placed in the system. The SJ antenna was

ovoid, originally solid but later a lattice, and unlike the SD it had a mast of

its own. The last wartime set was the SS.

Sonars, too, were being constantly improved, and by 1945

most US submarines had the active WFA system, which combined echo-ranging,

listening and sounding using a retractable keel-mounted dome. The latter

feature prevented the sonar from being used when the submarine was lying on the

bottom, and a passive listening device was therefore mounted topside. Initially

the JP, a converted surface patrol craft set, was used; like the later JT it

enabled the submarine to detect surface ship propeller noise at ranges of up to

20.000 yards (18.288m] and was also used to detect self-noise. The JP was

manually rotated but the later it was powered and consisted of a 5ft (1.53m)

line hydrophone with a 22° beam scanning at 4rpm. It covered the sonic

(100Hz-12kHz) and, with a converter supersonic (up to 65kHz) frequencies. A new

and highly specialised type of sonar came into use late in the war: the FM,

later redesignated QLA-1, was a precision mine-evasion sonar which was so

effective that US submarines were able to work in Japanese home waters with

relative confidence.

Other sensors included the usual two periscopes. Number 1

for search and Number 2 for attack, and there was a variety of radio masts,

whip antennas and stubs, the actual fit changing with bewildering rapidity.

Electronic warfare equipment also began to be fitted, one external indication

being a large direction-finding loop. Finally, for surface actions with the

gun, there were two target bearing transmitters mounted on the bridge.

Armament

As built, the Gatos were armed with one 3in/50gun in line

with the prewar policy of ensuring that a submarine captain would not be given

a gun which might encourage him to fight it out on the surface. However,

weapons were progressively added throughout the war and by 1945 armament

normally comprised one 5in/25gun and two 40mmand two twin 20mm cannon. By 1950.

however, the Guppy conversion programme (described below) had eliminated the

guns.

There were ten 21 in torpedo tubes, six forward and four

aft. with 24 reloads, and while the boats themselves were very reliable the

torpedoes were far less so. Certainly, the Mk 14 torpedo with its Mk Vl

magnetic exploder used from 1941 to 1943 was notoriously unreliable; the

torpedo ran much deeper than designed and left a prominent wake, while the

exploder frequently failed to detonate and the back-up contact exploder only

seemed to work when hitting the target a glancing blow. Later in the war the Mk

18 torpedo, a direct copy of a captured German G7e, was widely used, and was

credited with sinking a million tons of Japanese shipping.

Construction

The 73 boats of the Gato class were launched between 1941

and 1943, construction being shared between Electric Boat, Groton (41),

Portsmouth Navy Yard (14), Mare Island Navy Yard (4) and Manitowoc, Wisconsin

14. Of the 54 that survived the war. most were converted to Guppy 1 (Greater

Underwater Propulsive Power) standard: all guns and other external protuberances

were removed, the sail was streamlined, a schnorkel was fitted and new, lighter

and much more powerful batteries were fitted. This conversion based on the

lessons of the German Type XXI, had a dramatic effect on performance, with

considerable increases in underwater speed and range. Of the remaining boats

six were transferred abroad and seven converted to hunter-killer submarines

with more powerful batteries for a higher underwater speed. Another six were

converted to radar pickets in 1951-52. with an extra 31ft (8.3m) portion added

to their hulls. Tunny (SS-282) was converted into a Regulus 1 missile launching

submarine and was then again altered to a troop-carrying submarine in 1964.