The Foxtrot class was the NATO reporting name of a class of diesel-electric patrol submarines that were built in the Soviet Union. The Soviet designation of this class was Project 641. The Foxtrot class was designed to replace the earlier Zulu class, which suffered from structural weaknesses and harmonic vibration problems that limited its operational depth and submerged speed. The first Foxtrot keel was laid down in 1957 and commissioned in 1958 and the last was completed in 1983. A total of 58 were built for the Soviet Navy at the Sudomekh division of the Admiralty Shipyard (now Admiralty Wharves), St. Petersburg.[1] Additional hulls were built for other countries.

In the Cold War era, that commitment began with the massive

submarine construction programs initiated immediately after World War II-the

long-range Project 611/Zulu, the medium-range Project 613/Whiskey, and the

coastal Project 615/Quebec classes. Not only did these craft serve as the

foundation for the Soviet Navy’s torpedo-attack submarine force for many years,

but converted Zulus and Whiskeys were also the first Soviet submarines to mount

ballistic and cruise missiles, and several other ships of these designs were

employed in a broad range of research and scientific endeavors.

These construction programs were terminated in the mid-1950s

as part of the large-scale warship cancellations that followed dictator Josef

Stalin’s death in March 1953. But the cancellations also reflected the

availability of more-advanced submarine designs. Project 641 (NATO Foxtrot)

would succeed the 611/Zulu as a long-range torpedo submarine, and Project 633

(NATO Romeo) would succeed the 613/Whiskey as a medium-range submarine. There

would be no successor in the coastal category as the Soviet Navy increasingly

undertook “blue water” operations. Early Navy planning provided for the

construction of 160 Project 641/ Foxtrot submarines.

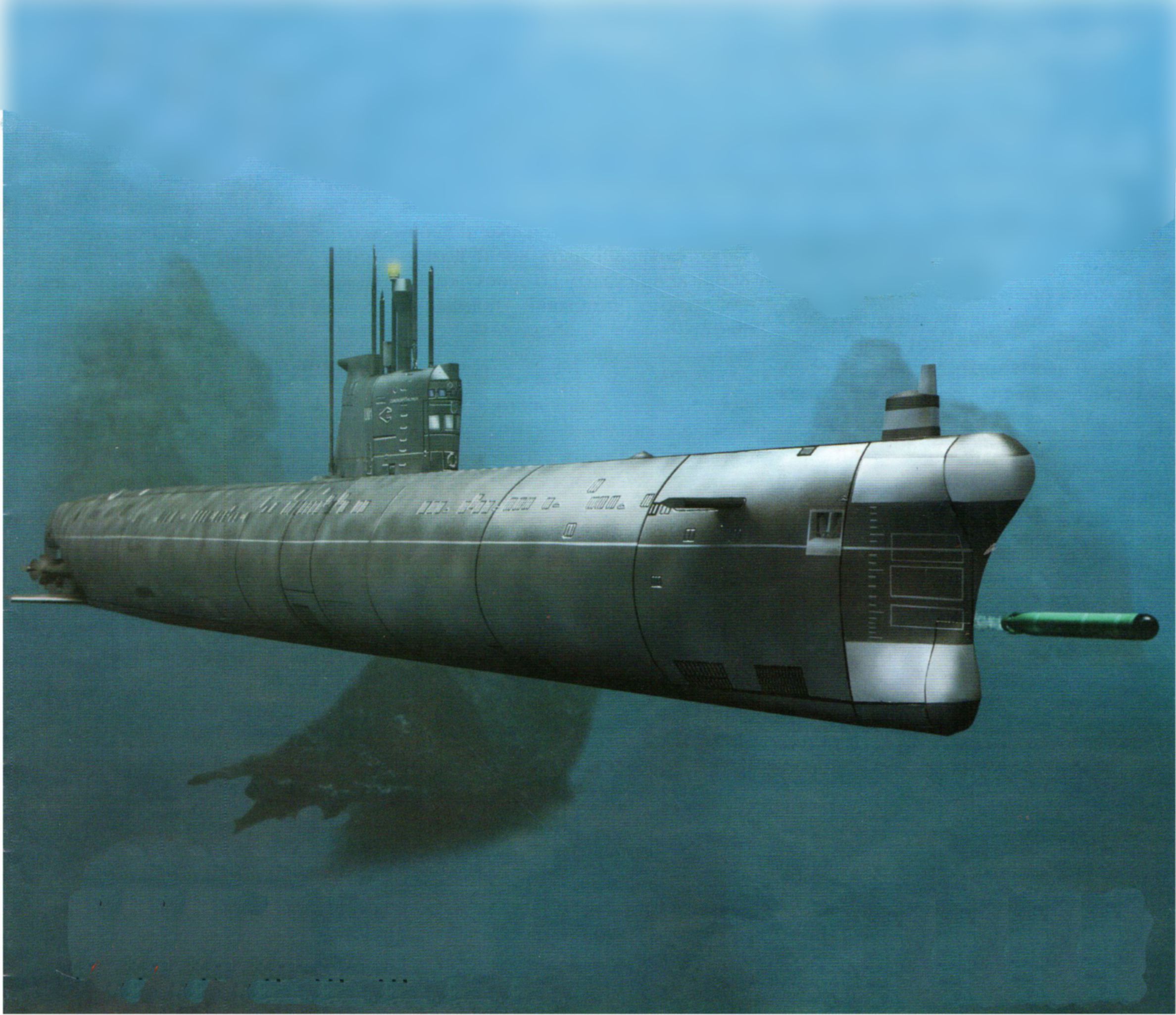

Designed by Pavel P. Pustintsev at TsKB-18 (Rubin), Project

641 was a large, good-looking submarine, 2991/2 feet (91.3 m) in length, with a

surface displacement of 1,957 tons. Armament consisted of ten 21-inch (533-mm)

torpedo tubes-six bow and four stern. Project 641/Foxtrot had three diesel

engines and three electric motors with three shafts, as in the previous Project

611/Zulu (and smaller Project 615/Quebec). Beyond the increase in range brought

about by larger size, some ballast tanks were modified for carrying fuel.

Submerged endurance was eight days at slow speeds without employing a snorkel,

an exceptional endurance for the time. The Foxtrot introduced AK-25 steel to

submarines, increasing test depth to 920 feet (280 m). The large size also

provided increased endurance, theoretically up to 90 days at sea.

The lead ship, the B-94, was laid down at the Sudomekh yard

in Leningrad on 3 October 1957; she was launched-64 percent complete-in less

than three months, on 28 December. After completion and sea trials, she was

commissioned on 25 December 1958. Through 1971 the Sudomekh Admiralty complex

completed 58 ships of this design for the Soviet Navy.

Additional units were built at Sudomekh from 1967 to 1983

specifically for transfer to Cuba (3), India (8), and Libya (6). The Indian

submarines were modified for tropical climates, with increased air conditioning

and fresh water facilities. Later, two Soviet Foxtrots were transferred to

Poland. The foreign units brought Project 641/Foxtrot production to 75

submarines, the largest submarine class to be constructed during the Cold War

except for the Project 613/Whiskey and Project 633/Romeo programs.

(Two Project 641 submarines are known to have been lost, the

B-37 was sunk in a torpedo explosion at Polnaryy in 1962 and the B-33 sank at

Vladivostok in 1991.)

The Soviet units served across the broad oceans for the next

three decades. They operated throughout the Atlantic, being deployed as far as

the Caribbean, and in the Pacific, penetrating into Hawaiian waters. And

Foxtrots were a major factor in the first U.S.-Soviet naval confrontation.

PURPLE-NOSED TORPEDOES

Standing on the deck of his submarine, staring at a

strange-looking torpedo, Captain First Rank Ryurik Ketov flipped up the collar

on the back of his navy blue overcoat to shield his neck from the cold. A

fading September sun coated the waters of Sayda Bay and reflected remnants of

orange and yellow from the sides of a floating crane. The crane hovered over

Ketov’s boat and lowered a purple-tipped torpedo through the loading hatch.

Within minutes the long cylinder disappeared into the forward torpedo room.

Blowing into his gloved hands to keep his nose warm, Ketov glanced at the

submarine’s conning tower. Three large white numbers were painted on the side,

but Ketov knew this label held no meaning, except to serve as a numerical decoy

for enemy eyes. The boat’s real designation was B4—B as in Bolshoi, which means

“large.”

The handsome, blue-eyed Ketov inherited his B-4 Project 641

submarine—known as a Foxtrot class by NATO forces—from his former commander,

who was a drunk. Tradition dictated that submarine captains who were too

inebriated to drive their boats into port should lie below until they sobered

up. First officers took charge and positioned a broomstick on the bridge in

their captain’s stead. Atop the handle they placed the CO’s cap so that

admirals on shore peering through binoculars would raise no eyebrows. Ketov

stood watch with a broom more times than he could recall. He didn’t dislike

vodka, nor did he disapprove of his CO’s desire to partake, but Ketov felt that

a man must know his limits and learn to steer clear of such rocks when under

way. He demanded no less of his crew. Unfortunately, as his appointment to

commander required the approval of the dozen sub skippers in his group, and all

of them drank like dolphins, Ketov’s stance on alcohol held him back for a year

when he came up for promotion.

The Soviet navy formed the sixty-ninth Brigade of Project

641 submarines in the summer of 1962. Ketov and his comrade captains were

ordered to prepare for an extended deployment, which they suspected might be to

Africa or Cuba. Some wives, filled with excitement, anticipated a permanent

transfer to a warm locale.

The four subs arrived in Gadzhiyevo at Sayda Bay a month

earlier and were incorporated into the Twentieth Submarine Squadron along with

the seven missile boats. Vice Admiral Rybalko assumed command of the squadron,

and over the next thirty days, each boat was loaded with huge quantities of

fuel and stores.

Now, aboard B-4, Captain Ketov coughed into the wind and

turned to stare at the weapons security officer. Perched near the crane, the

man shouted orders and waved long arms at the fitful dockworkers. The officer’s

blue coveralls and pilotka “piss cutter” cap signified that he belonged to the

community of submariners, but Ketov knew better. The shape of a sidearm bulged

from under the man’s tunic, and his awkwardness around the boat made it obvious

that he was not a qualified submariner.

Ketov also knew that the security officer came from Moscow

with orders to help load, and then guard, the special weapon. Although he’d not

yet been briefed about the weapon, Ketov figured this torpedo with the

purple-painted nose, which stood in sharp contrast against the other gray

torpedoes on board, would probably send a radiation Geiger counter into a

ticking frenzy.

Ketov looked down at the oily water that slapped against the

side of his boat. Attached by long steel cables, three sister boats of the

Soviet Red Banner Northern Fleet floated nearby. If one approached these

late-model attack subs from the front, their jet-black hulls, upward-sloping

decks, and wide conning towers with two rows of Plexiglas windows might look

menacing. The silver shimmer of their sonar panels, running across the bow like

wide strips of duct tape, might appear odd. The reflective panels of the

passive acoustic antenna, jutting from the deck near the bow, might look

borrowed from the set of a science-fiction movie. But the seasoned sailors on

the decks of these workhorses were unmistakably Russian, and undeniably

submariners.

Ketov strutted across the wooden brow that connected B-4 to

the pier. Two guards, with AK-47 assault rifles slung on their shoulders,

snapped to and saluted. Ice crunched under his boots as he walked toward a

small shed less than a hundred meters away. Captain Second Rank Aleksei

Dubivko, commander of B-36, matched his stride and let out a baritone grunt.

“Did they give you one of those purple-nosed torpedoes?”

“Yes,” Ketov answered, “they did.”

Although the round-faced commander was about Ketov’s height

of five foot seven, Dubivko’s stocky frame stretched at the stitches of his

overcoat. He let out another grunt and said, “Why are they giving us

nuclear-tipped weapons? Are we starting a war?”

“Maybe,” Ketov said. “Or maybe we’re preventing one.”

Dubivko’s boots clicked on the ice as he hurried to keep up

with Ketov. “We haven’t even tested these weapons. We haven’t trained our

crews. They have fifteen-megaton warheads.”

“So?”

“So if we use them, we’ll wipe out everything within a

sixteen-kilometer radius. Including ourselves.”

Ketov neared the door of the shed and stopped to face

Dubivko. “Then let’s hope we never have to use them.”

Dubivko let out a low growl and followed Ketov into the

shack.

Inside, Captain First Rank Nikolai Shumkov, commander of

submarine B-130, stood by the door. Only a few stress lines underscored his

brown eyes and marked his boyish features. Next to Shumkov, Captain Second Rank

Vitali Savitsky, commander of B-59, appeared tired and bored. None of them had

slept much since their trip from Polyarny to Sayda Bay.

The tiny shed, once used for storage, offered no windows. A

single dim bulb hung from the ceiling and cast eerie shadows inside. Someone

had nailed the Order of Ushakov Submarine Squadron flag on one wall. The

unevenly placed red banner, fringed in gold and smeared with water stains,

appeared as if hung by a child in a hurry. In one corner sat a small stove that

flickered with yellow sparks but offered little warmth. The air smelled of

burnt coal.

One metal table graced the center of the room, where the

squadron commander, Leonid Rybalko, sat with his arms crossed. Ketov noticed

that the vice admiral shivered, despite being bundled in a dark navy greatcoat

and wool senior officers’ mushanka cap. The tall, broad-shouldered Rybalko had

a reputation for analytical brilliance and a smooth, engaging wit. A dedicated

performer, Rybalko exuded the confidence and mastery of a seasoned leader.

To the side and behind Rybalko, the deputy supreme commander

of the Navy Fleet, Admiral Vitali Fokin, fidgeted with his watch. Thin and

lofty, Fokin kept his back straight. Ketov deduced that Fokin, given his close

relationship with Fleet Admiral Sergei Gorshkov, held the reins of what ever

mission they were about to undertake. A slew of other officers filled the room,

including Anatoly Rossokho, the two-star vice admiral chief of staff. Ketov

suspected that Rossokho was here to define their rules of engagement about

using the special nuclear torpedoes.

Vice Admiral Rybalko motioned for everyone to find a seat.

He coughed and brought a handkerchief to his lips to spit out a clump of mucus.

His face looked pale and sickly. He locked his eyes on each submarine commander

one at a time. When he looked at Ketov, those few moments seemed like days.

“Good morning, Commanders,” Rybalko said. “Today is an

important day. I’m not going to discuss mission details, as we’ve included

those in your sealed briefings, which you will open under way. So instead we

will focus on other aspects of your mission.”

Metal clanked as an attendant creaked open the front panel

on the hot stove and dumped in another can of coal pellets.

Rybalko continued. “I’m sure you all know Admiral Fokin. He

asked me to emphasize that each of you has been entrusted with the highest

responsibility imaginable. Your actions and decisions on this mission could

start or prevent a world war. The four of you have been given the means with

which to impose substantial harm upon the enemy. Discretion must be used.

Fortunately, our intelligence sources report that American antisubmarine

warfare activity should be light during your transit.”

Ketov hoped that the ASW intelligence report was correct but

feared that optimism probably overruled reality. He glanced at the other sub

commanders. Dubivko and Shumkov wore excited smiles. Savitsky, who’d earned the

nickname “Sweat Stains” because he was always perspiring about something,

wrinkled his brow. Ketov, who received the title of “Comrade Cautious,” shared

Savitsky’s angst. As adventurous as this might seem to Dubivko and Shumkov,

Ketov knew Project 641 submarines were not designed for extended runs into hot

tropical waters and had no business carrying nuclear torpedoes.

Rybalko imparted more information, concluded his speech, and

asked if anyone had questions.

Ketov raised a hand. “I do, Comrade Admiral. I understand

that our sealed orders provide mission details, but we share concerns about our

rules of engagement and the special weapon. When should we use it?”

Vice Admiral Rossokho broke in. “Comrade Commanders, you

will enter the following instructions into your logs when you return to your

submarines: Use of the special weapons is authorized only for these three

situations—One, you are depth charged, and your pressure hull is ruptured. Two,

you surface, and enemy fire ruptures your pressure hull. Three, upon receipt of

explicit orders from Moscow.”

There were no further questions.

After the meeting, Ketov followed the group out into the cold.

A witch’s moon clung to the black sky and hid behind a dense fog that touched

the ground with icy fingers. Ketov reached into his coat pocket and took out a

cigarette. Dubivko, standing nearby, held up a lighter. Ketov bent down to

accept the flame. Captains Shumkov and Savitsky also lit smokes as they

shivered in the dark.

Between puffs, Ketov posed the first question to Captain

Savitsky. “How are your diesels holding up?”

Savitsky cringed. “No problems yet, but I’m still worried

about what might happen after they’ve been run hard for weeks. If they fail on

this mission…” Savitsky’s voice trailed off as he shook his head.

Ketov knew that shipyard workers had discovered flaws in

B-130’s diesel engines during the boat’s construction. The shipyard dismissed

the hairline cracks as negligible, and Savitsky did not press the issue, as to

do so would have resulted in his sub’s removal from the mission. Still, he

fretted endlessly about the consequences.

Sensing his friend’s distress, Ketov changed the subject.

“Have you seen those ridiculous khaki trousers they delivered?”

“I’m not wearing those,” Savitsky said.

“I wouldn’t either,” Shumkov said, “if I had your skinny

duck legs.”

Savitsky snorted and threw his head back. “I’d like to see

how you look in those shorts, Comrade Flabby Ass.”

“Right now,” Dubivko said as he pulled his coat tighter,

“I’d rather look like a duck in shorts than a penguin in an overcoat.”

Ketov smiled and shook his head. “I’m going back to my boat,

try on those silly shorts, and have a long laugh and a can of caviar.”

“And maybe some vodka?” Shumkov said.

“I wish,” Ketov said. “We cast lines at midnight.”

Shumkov nodded and said nothing.

Savitsky raised his chin toward Ketov. “Do you think we’re

coming back or staying there permanently?”

Ketov shrugged. “All I know is that we can’t wear those

stupid shorts in this weather.”

Back on board B-4, Captain Ketov sat on the bunk in his

cabin and stroked the soft fur of the boat’s cat. “It’s time to go, Pasha.”

Over the past year, the calico had become a close member of

B-4’s family. Like many Russian submarines, B-4 enlisted the services of

felines to hunt down rats that managed to find their way on board, usually by

way of one of the shorelines. Boats often carried at least one or two cats on

board, and the furry creatures spent their entire lives roaming the decks in

search of snacks and curling up next to sailors on bunks. Unfortunately, for

reasons unknown, headquarters decreed that cats were forbidden on this journey.

Given no choice, Ketov found a good home for Pasha with a friend who could care

for her and keep her safe.

As Pasha purred by his side, Ketov reached for a can of

tuna. “The least I can do is give you a nice snack before we leave.”

Ketov thought about his mother, still living in the rural

Siberian village of Kurgan. She’d lost her husband to one war; would she now

sacrifice her first born son? When Ketov was thirteen, his father, who was an

accountant with bad eyesight, was forced to fight in the battle at Leningrad.

He was killed in his first engagement. Ketov became the man of the house and

helped support his younger siblings and his mother, who earned a meager

teacher’s salary. He could still not explain why, but the day he turned

eighteen, one year after the war ended, he took the train to Moscow and

enrolled in the naval college. He also had no explanation for why he’d jumped

at the chance to serve aboard submarines. He only knew that, despite the

sacrifices and often miserable conditions on the boats, no other life could

fulfill him like the one under the sea.

A few minutes past midnight on October 1, 1962, Captain

Ketov stood on the bridge of B-4 and watched Captain Savitsky cast off lines

and guide B-59 away from the pier using her quiet electric motors. Captain

Vasily Arkhipov, the brigade’s chief of staff, stood next to Savitsky in the

small cockpit up in the conning tower. A flurry of snow mingled with the fog

and dusted the boat’s black hull with streaks of white. Thirty minutes later,

B-36, commanded by Dubivko, followed in the wake of her sister sub and

disappeared into the darkness of the bay. After another thirty minutes,

Shumkov, in B-130, followed by Ketov in B-4, maneuvered away from the pier.

Ketov stared into the blackness as the three subs ahead of him, all with

running lights off, vanished into the night. Then he heard the low rumble of

B-59’s diesel engines, signaling that Savitsky had cleared the channel and

commenced one of the most important missions undertaken by the Russian navy

since World War II.