William Marshal’s victory prevented a foreign prince

from ruling England, but Lincoln’s citizens had little cause for celebration.

Perviously the French were unable to capture Lincoln Castle, governed by the formidable Nichola de la Haye.

The rebels invited the king of France to take the throne of England; instead Philip II’s son, Louis (the future Louis VIII), accepted the offer and was hailed as King of England in London in June of 1216. In the same year Nichola prevented another siege by paying off a rebel army, led by Gilbert de Gant, who had occupied the city of Lincoln.

As Louis consolidated his position in the south, John made an inspection of Lincoln castle in September 1216. During the visit Nichola de la Haye, who held the castle for John, even though the city supported the rebels, was appointed Sheriff of Lincolnshire in her own right.

Moving south, just 2 weeks later, the

king’s baggage train was lost as he crossed the Wash estuary and within a

few more days John was desperately ill.

King John died at Newark on 19th October 1216.

BATTLE MAP: 1. Position of the former West Gate, where

William Marshal entered the city 2. Lincoln’s North Gate, which was assaulted

by the Earl of Chester 3. The Cathedral, which was looted by Henry III’s forces

4. Castle Square, where the French were held up by Marshal’s crossbowmen and

where the main battle action took place 5. The lower town, where the French and

the rebels were chased south. The town was ransacked by Marshal’s troops,

giving the battle the name `the Battle of Lincoln Fair.

While most people have heard of Hastings, Crécy, Agincourt

and Bosworth, few have heard of the Battle of Lincoln, and even fewer know that

had it not been for that battle, England might well have been ruled by a King

Louis the First.

Towards the end of King John’s reign, the barons of England

rebelled at what they saw as his arbitrary and vindictive rule. In June 1215,

John temporarily appeased them by agreeing to what would later be called Magna

Carta, a document addressing the perceived abuses of his reign. But when Magna

Carta was withdrawn less than three months later, many English barons concluded

that there was no doing business with John and invited Louis, the son of Philip

Augustus of France, to replace him as the king of England.

Louis duly invaded, and with the support of the rebel

barons, he overran much of southeast England and East Anglia, although the

castles at Windsor and Dover stubbornly held out against him. Then, in October

1216, John did what has been described as the best thing he ever did for his

country. He died. Much of the baronial support for Louis had been motivated by

a hatred of John, and now that he was no longer on the scene, many barons

switched sides in favour of his successor, the nine-year-old Henry III,

especially when his advisors re-issued Magna Carta. Even so, Louis didn’t

abandon his attempts to conquer England, and while half his army continued to

besiege Dover Castle, he sent the rest north to capture Lincoln.

At the time, Lincoln was one of the largest and most

important cities in the country. Perched on the top of a steep hill, it was

surrounded by stone walls and defended by a powerful castle. The castle had two

fortified mounds and two main gates, one leading into the city and the square

opposite Lincoln’s cathedral, and the other westward into the countryside. In 1217,

the castle’s constable was a woman in her 60s, Nichola de la Haye.

Although the castle would prove a tough nut to crack, the

city itself wasn’t prepared to resist a full-scale attack and quickly

surrendered to the forces of Louis, who arrived in March under the command of

the young Comte du Perche and Saer de Quincy, the Earl of Winchester and a

leader of the baronial rebellion. But, with the redoubtable Nichola in command,

the castle held out even though the French brought up siege engines – probably

trebuchets – to bombard its walls.

William Marshal, the regent of England and commander of the forces

loyal to Henry III, was determined not to let such an important stronghold fall

into the hands of Louis. He gathered together a relief force, which assembled

at Newark before heading for Lincoln. They realised that although the main road

entered the city from the south, an approach from that direction was highly

undesirable. Before they could get to the castle, they would have to fight

their way through the town and up a precipitous road that even today is known

as `Steep Hill’. So they marched on Lincoln via Torksey, approaching the city

from the north-west on Saturday 20 May.

Perche and his men saw them coming and, according to one

chronicler, a small reconnaissance force of English rebels went out to check

out the approaching threat. They reported back that William Marshal’s army was

not a particularly large one, and argued that the best course of action was to

leave the city and take them on in the open fields, where their own superior

numbers could prove decisive. The chronicler says that Perche was unconvinced

and sent out a second reconnaissance force, this time made up of French

knights. At the time, a quick way of estimating the strength of an enemy army

was to count the banners of its knights, but this account claims that the

French were unaware of the fact that each English knight carried two banners

and therefore concluded that Marshal’s army was twice as strong as it actually

was. Whether this actually happened isn’t known Perche’s English troops would

have put them right – but in any event, the French decided to remain behind the

safety of the city walls, thus handing the initiative over to Marshal.

Meanwhile, Marshal’s men were arguing about who should have

the honour of leading the assault, with the powerful Earl of Chester

threatening to go home if it wasn’t him. In fact, it didn’t really matter – for

Marshal’s plan was to mount a series of simultaneous attacks from a variety of

directions. While the Earl of Chester led the assault on the city’s North Gate,

drawing the French in that direction, Marshal himself attacked the West Gate.

It was said that he was so keen to join the battle that as he was beginning to

move his column, a page had to remind him that he had forgotten to put his

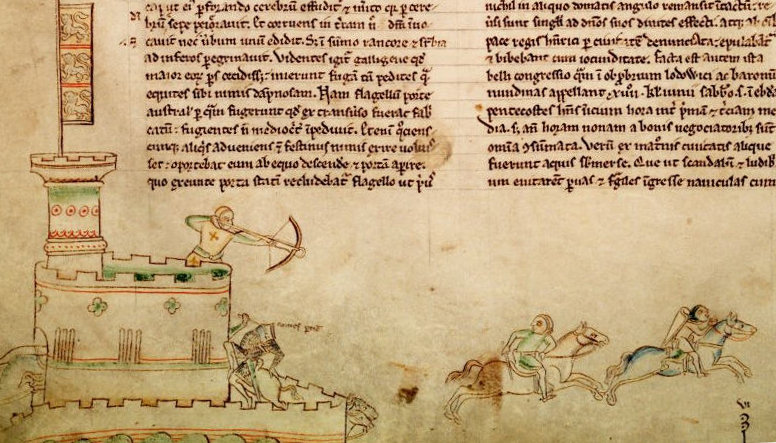

helmet on. Meanwhile, 300 crossbowmen under Falkes de Breauté, one of Henry

III’s most loyal and ruthless commanders, slipped into the castle through a

postern gate that opened outside the city walls. They took up position on the

castle walls and poured down a deadly shower of crossbow bolts onto the French

below them. Marshal and the Earl of Chester both broke into the city and soon

Lincoln’s cramped streets were filled with a mass of struggling men. One

contemporary described the scene:

“Had you been there you would have seen great blows

dealt, heard helmets clanging. seen lances fly in splinters in the air, saddles

vacated by riders. great blows delivered by swords and maces on helmets and on

arms, and seen knives and daggers drawn for stabbing horses.”

The turning point came when Breauté led the castle’s

garrison out of its East Gate and joined in the fray. Initially, they were

driven back and Breauté was temporarily taken prisoner before being rescued,

but their intervention probably tipped the scales in favour of Marshal, and

when the Comte du Perche was killed by a lance thrust through the eye-slit of his

helmet, the French lost heart. They were steadily driven back down Lincoln’s

steep main street until they reached the gate at the south end of the city,

which was so narrow that few could escape. While we have no idea of what

happened to their ordinary soldiers – the chroniclers at the time simply

weren’t interested in them – many of the knights in the French and rebel army

were taken prisoner.

The battle was won but the destruction and bloodshed wasn’t

yet over. The victorious English considered that the city had surrendered

rather too quickly to the French and, suspecting it of collaboration, meted out

a savage punishment. The entire city was thoroughly sacked. Even the cathedral (whose

clergy had been excommunicated by the Papal Legate accompanying the English

army) was pillaged. As the panic-stricken residents tried to save themselves

and their property from Marshal’s marauding soldiers, tragedy struck. According

to the chronicler Roger of Wendover:

“Many of the women of the city were drowned in the

river for, to avoid shameful offence (ie rape), they took to small boats with

their children, their female servants, and household property. the boats were

overloaded, and the women not knowing how to manage the boats, all

perished.”

As Marshal’s victorious troops left Lincoln, they were so

laden with booty and plunder that it looked to onlookers as though they had

been on some enormous shopping expedition, with the result that the battle

gained its unlikely nickname – Lincoln Fair.

THE MAN WHO WAS NEARLY KING

Prince Louis was the son of Philip Augustus, King of France

and Richard the Lionheart’s partner (and rival) during the Third Crusade. He

was born in 1187 and in 1200 he married Blanche of Castile, a granddaughter of

Henry II. At a time when you didn’t necessarily have to be next in line in

order to take the throne, Louis, who did have royal blood after all, seemed an

ideal replacement for the tyrannical John. To the English barons who asked him

to be their king Louis was all the things John wasn’t – brave, pious,

trustworthy and a man who kept his word. After landing in England he was

proclaimed king in London, and within months about two thirds of the barons and

more than half of the country were under his control. After the failure of his

bid to rule England, Louis returned to France where he succeeded to the throne

as Louis VIII in 1223 and promptly conquered large amounts of the remaining

English territory in the country.