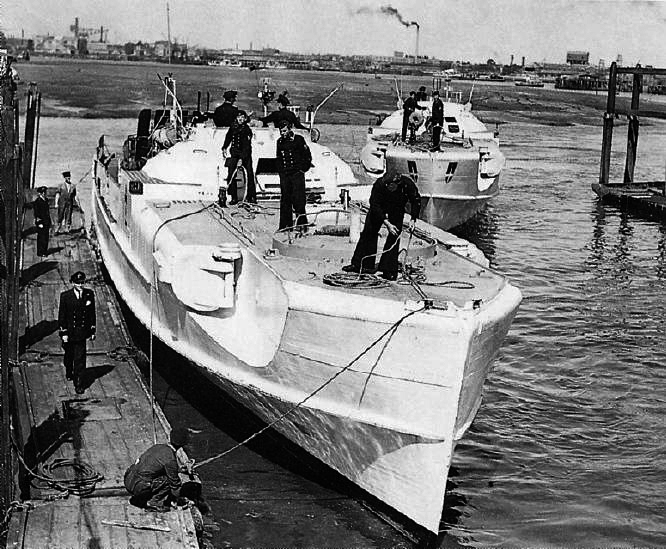

Schnellboot S31 of the same class [Schnellboot

1939 Class] as S34

So far, German naval activity off Dunkirk had been

non-existent, but this situation was not to last. In the early hours of 28 May

Kapitänleutnant Rudolf Petersen, commanding the 2nd Schnellboote Flotilla in

Wilhelmshaven, called his officers together and briefed them for offensive

operations in the Channel area. Already, on 9 May, Petersen had led four boats

of his flotilla in a successful night action north of the Straits of Dover;

they had encountered a force of cruisers and destroyers of the British Home

Fleet, and in the ensuing brief battle the destroyer HMS Kelly had been

torpedoed and badly damaged by Kapitänleutnant Opdenhoff’s S31.15

Now, three weeks later, Petersen’s orders were simple: the

S-boats were to enter the Channel under cover of darkness, lie in wait and

strike hard at whatever British vessels they encountered, preferably those

homeward bound with their cargoes of troops. Six boats were to undertake the

mission, operating in two relays of three, hugging the 200 miles (320km) of

coast on the outward trip and entering the Channel after dark.

The first three boats slipped out of Wilhelmshaven that

afternoon. In the lead was S25, commanded by Kapitänleutnant Siegfried

Wuppermann, an officer who was later to become one of the German Navy’s small

ship ‘aces’ in the Mediterranean. Behind him came Leutnant Zimmermann’s S30,

followed in turn by S34 under Leutnant Obermaier. The outward voyage was

uneventful, the S-boats entering the Channel on schedule and spreading out,

evading the slender screen of MTBs deployed by the Royal Navy from Felixstowe

and taking up station, engines off, to the north of Ramsay’s cross-Channel

routes. Station was kept, from left to right, by S30, S25 and S34, and after 90

minutes of pitching and waiting on the Channel swell it was Obermaier in S34

who made the first contact with the enemy. With the aid of night glasses, he

picked out a vessel and identified it as a British destroyer. Starting S34’s

engines, he closed to action stations and began his attack. At 0045 on 29 May,

he launched four torpedoes at the target.

Among the crew of the destroyer HMS Wakeful, the tension of

the day’s operations was making itself felt. Hardly had the destroyer entered

Dover with her first load of troops on 28 May when she was ordered out again,

and she had sailed as soon as the soldiers disembarked, still without having

refuelled or taken on fresh stocks of ammunition. On her second trip across the

Channel she had been attacked by Ju 87s and had sustained a hole in her side

from a near-miss, but she had run the gauntlet of the attack and Commander

Fisher had brought her back into Dunkirk, taking on another 640 troops. Now he

was taking his ship home over Route Y, the most northerly of the evacuation

routes, with the light of the Kwinte Buoy visible to port.

There was no time for evasive action. The first of S34’s

torpedoes passed ahead of the destroyer but the second exploded amidships,

tearing Wakeful in two. Within 30 seconds she was gone, leaving behind a few

islands of wreckage and a handful of survivors, Fisher among them. Over 700

men, mostly troops crammed below decks, went to their deaths with the stricken

ship.

Other vessels in the vicinity observed the disaster and

closed in to give whatever help they could. The survivors had been in the water

for little over 30 minutes when the first arrived: the minesweeper HMS

Gossamer, closely followed by the Scottish drifter Comfort. By 0200 hours the

destroyer Grafton, the minesweeper Lydd and the motor drifter Nautilus had also

reached the scene, their lifeboats joining the search for the remnants of

Wakeful’s crew.

A thousand yards to the east, other eyes were watching the

rescue operation. They belonged to Leutnant Michalowski and they were glued to

the eyepiece of a periscope in the control centre of the submarine U-62.

Michalowski now focused on the largest of the English vessels, clearly visible

in the periscope’s graticule as lights flickered across the water amid

Wakeful’s wreckage. Michalowski quickly checked range, bearing, depth settings

and running time, then ordered the launch of a salvo of torpedoes.

The destroyer Grafton was lying at rest, her rails crowded

with troops who, like her captain, Commander Robinson, were watching the

efforts of her lifeboat crews as they continued the search. At that instant

U-62’s torpedoes struck. One tore away the destroyer’s stern; the other sent an

explosion ripping through the wardroom, killing 35 officers.

What happened next amounted to panic. The other vessels in

the area, their captains aware only that Grafton had been subjected to an

unexpected attack, began steering in all directions, their gun crews tense and

ready to fire at shadows. On the minesweeper Lydd, Lieutenant-Commander Haig

saw what looked like the silhouette of a torpedo-boat moving south-westwards.

Lydd’s starboard Lewis gun opened fire on it and Grafton, which was still

afloat, opened up with her secondary armament. It was a terrible mistake; the ‘torpedo-boat’

was in fact the drifter Comfort, carrying survivors from HMS Wakeful.

Machine-gun bullets raked her decks as the Lydd closed right in, cutting the

drifter’s crew to pieces. Minutes later, Lydd’s bow sliced into Comfort’s hull,

tearing her apart. There were only five survivors; among them was Commander

Fisher, whom Comfort had plucked from the sea when Wakeful went down. Fisher

spent a long time in the water before be was again picked up, more dead than

alive, by the Norwegian tramp steamer Hird at dawn.

HMS Grafton, meanwhile, was finished. At first light the

railway steamer Malines took off her survivors, and soon afterwards the

destroyer Ivanhoe put three shells into her waterline. Ten minutes later she

turned over and sank. Over the horizon U-62 and Wuppermann’s three S-boats were

already well on their way back to base; there could be no doubt that the German

Navy had won the first round.

During the late afternoon of 1 June, the French naval

vessels off Dunkirk once again came in for severe punishment; at 1600 Stukas

fell on a convoy of French auxiliaries, sinking three of them – Denis Papin,

Venus and Moussaillon – within five minutes.

RAF Fighter Command carried out eight squadron-strength

patrols during the course of the day, claiming the destruction of 78 enemy

aircraft – a figure that was later officially reduced to 53. However, Luftwaffe

records admit the loss of only 19 bombers and ten fighters for 1 June, with a

further 13 damaged; and since the Royal Navy claimed ten aircraft destroyed and

French fighters another ten, the actual score must remain in doubt. What is

certain is that Fighter Command lost 31 aircraft during the air battles of 1

June, and that the evacuation fleet lost 31 vessels of all types sunk – including

four destroyers – and 11 damaged. Most of the stricken vessels fell victim to

air attack, but it was the German Navy that had the last word. Shortly before

midnight, Leutnant Obermaier, making yet another sortie into the Channel in

Schnellboot S34, sighted two ships and attacked with torpedoes, sinking both.

They were the trawlers Argyllshire and Stella Dorado.

Despite the losses, the evacuation fleet lifted off 64,429

British and French troops on 1 June. Since the last stretches of beach still in

Allied hands, and the shipping offshore, were now being heavily shelled,

Admiral Ramsay planned to lift as many men as possible in a single operation on

the night of 1/2 June. It had originally been planned to complete the

evacuation on this night, but this was no longer feasible; there could be no

question of abandoning the French troops who had fought so hard on the

perimeter, and through whom the British had passed on their way to the beaches.

Ramsay therefore decided to concentrate all available ships after dark in the

Dunkirk and Malo areas, from where the maximum lift might be obtained. For this

purpose he had at his disposal some 60 ships, together with the many small

craft still involved in the operation; the French could provide ten ships and

about 120 fishing craft.