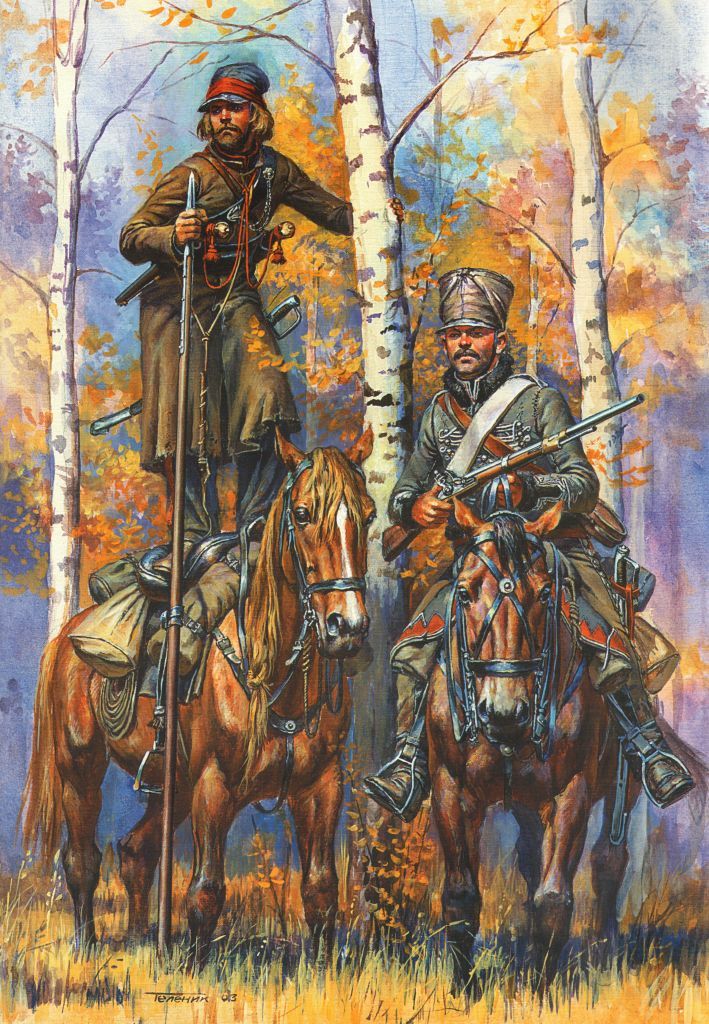

Russian guerrillas in 1812 that fought against northern regions of Russia against the French Empire invasion. Anatoly Telenik

MARAUDING PARTIES

No hay or straw – Le Roy commands a marauding party – ‘every

day the circle’s being drawn tighter’ – Césare de Laugier meets the locals – ‘I

asked him politely in Latin’ – Paul de Bourgoing fights his way out – Ney’s

reconnaissance in force

Nor is it only Murat’s men who are short of essentials. In a

Moscow stuffed with tea and coffee, jams and liqueurs, bread and – above all –

hay have quickly become rarities. Writing home around the turn of the month

(but his letter will be captured by Cossacks) a French NCO tells his sister

that ‘the horses are gnawing at their mangers for lack of it’. Even a general

of brigade like Dedem, nursing his bruised chest in his mill on the outskirts,

can’t

‘get a sack of oats without a permit from the

Quartermaster-General, and that was hard to obtain. Only hay and straw were

lacking. The Prince of Neuchâtel himself was sending out to the villages to get

some.’

Where has it all gone to? Evidently Daru is doing his job of

getting in stocks for the winter only too well. By no means all the villagers

have fled,

‘probably because flight had presented greater

difficulties, there being so many of them and the environs of Moscow being so

densely populated. Perhaps also because some who’d meant to flee hadn’t been

able to because the French army, as soon as it had taken possession of Moscow,

had spread out in all directions. Finally, it’s possible that, being more

affluent, they’d found it hard to abandon home and hearth.’

Whether the analysis of the artillery officer, the Marquis

de Chambray, is right or not, when Dedem sends a sergeant and some men to get

him some eggs, chickens, etc., with strict orders to pay for them, ‘taking’

only some hay, the peasants beg the soldiers to make haste, for fear of the

Cossacks; who treat them as an inferior species.

These are everywhere in the town’s environs. The very first

day after settling at Petrovskoï, Laugier had seen them hovering only a few

hundred yards away, waiting to pounce on anyone who strayed from the Italian

camp. At dawn on 21 September, notwithstanding Le Roy’s well-posted sentries,

‘the Guard Chasseurs who’d gone reconnoitring were driven

back at the double by enemy cavalry as far as the houses where I’d stationed my

two companies. Being under arms, they opened fire and shot down three Cossack

regulars. But that didn’t mean a dozen of our men weren’t stabbed by these

gentlemen’s lances.’

Dedem makes a pact with the local priest, allowing him to go

on ringing his church bell provided his parishioners supply him with

necessaries, but the men of the 4th Line, bivouacked with the rest of Ney’s III

Corps to the west of the city, have all this time been

‘so short of almost everything, and only with difficulty

managing to get hold of black bread and beer, that strong detachments were

having to be sent out to seize cattle in the woods where the peasants had taken

refuge, and yet often returning empty-handed. Such was the supposed abundance

from the looting. Though the men were covering themselves with furs, they soon

no longer had clothes or shoes. In short, with diamonds, precious stones and

every imaginable luxury, we were on the verge of starving to death.’

This being the state of affairs, marauding parties are the

only solution, not always a very successful one. Simple at first, they’ve soon

become exceedingly problematic:

‘Our outposts extended hardly two days’ march beyond the

town. The Emperor could get no certain information on the Russian army’s

position. The Russians, on the contrary, were informed about every movement we

made; and few days passed without our hearing painful news of their having

carried off such or such a battalion, such or such a squadron, sent out to

protect our marauders searching for food,’

writes Fezensac. At Davout’s headquarters in the monastery

at the Doroghomilov Gate his reluctant chief-of-staff General Baron L-F.

Lejeune – that future painter of elegant and colourful battle scenes – is daily

having to organize ever stronger expeditions. On 17 September, while the fire

had still been raging, one of his subordinates had sighted ‘a herd of cattle,

hidden in a marsh between two forests ten miles away’. And instantly orders had

come to Le Roy2 to take a mixed detachment from the 85th Line and go and grab

it. At blush of dawn next day, with a soldier to guide his party, he’d set off:

‘At 9 a.m. we got to the edge of the marsh. I had it

searched by two detachments of 50 men each and two officers who, each following

his own side of it, were to join up at the other side. In the event of their

seeing the herd or meeting with any resistance they were to warn me by firing

shots or by beat of drum.’

While the remainder of his detachment rests, Le Roy goes up

to a nearby isolated church, 200 yards to his right, between himself and the

Moskova, and sees, about five miles away on the left bank, in the direction of

the city, several foraging horsemen who’re returning at a brisk canter,

apparently pursued. On his own thickly wooded and deeply ravined river bank he

can see nothing. Yet the existence of a church seems to indicate a number of

small communities. By and by a Russian peasant appears, but doesn‘t notice him;

and at the same moment a drum roll tells him someone – or something – has been

captured without resistance. Half an hour later the head of a very variegated

herd of animals appears – oxen, cows, little ponies, sheep and pigs. ‘Having

massed them together, we set out to our left and followed a track which the

livestock seemed to follow of their own accord.’ Sure enough, it leads to a

village by the river, and into the courtyard of a ‘pretty château no Frenchman

from the Army had as yet visited’. Deciding to halt for a couple of hours to

rest his men, he notes that he’s now about seven and a half miles from his

camp. He’s just starting to count the captured herd when his son, a sergeant in

the 85th, brings him one of the château’s inhabitants.

‘He’d arrested him just as I, together with three others,

was getting out of a ferry. He tells the major he has evacuated his family to

another of his properties and has come to see whether the invaders have any

knowledge of it, and if not, to rescue some of his possessions. “Monsieur,” I

told him, [says Le Roy pompously, stretching truth further than it was ever

stretched before] ‘The French soldier only makes war on armed men. You have

nothing to fear. And if all Russians had done as you have, the countryside our

army has passed through wouldn’t have been ravaged.”’

With these words he sends off 50 men to explore the other

part of the village on the far bank of the river, which laps the edge of the

château’s garden. Muskets and lances have been found in the village – the

former of Russian manufacture, the latter simply long rods with a long nail or

knife blade at the end, the kind the Cossacks are using:

‘I assumed they belonged to peasants who were being

incited to rise against us, and that the persons we’d just arrested were

leading the insurrection. I tacitly decided to take these gentlemen to Moscow:

and, what strengthened me in this resolution, two of them seemed to be

disguised Russian officers. The elder was about forty, the youngest about

twenty. They were wearing French-style tail-coats, hussar-style boots with

spurs, had little moustaches and round hats. The other individual had a serious

air, a malicious eye, and the muscles in his face never stopped twitching. He

was dressed like the first ones, in French clothes, a furred cap, big and roomy

trousers strapped underfoot. I was going to question them when the master

arrived. I was astonished to hear him speak Russian to the fellow with the

sinister face and to hold his cap in his hand, while the other didn’t take his

hat off. His son said: ‘This gentleman has just had a meal prepared and we’ve

stewed it up.”’

And in fact the Russian invites all the detachment’s

officers to refreshment, ‘apologizing for not being able to treat us as we

deserved. He’d also provided beer for the men.’ Le Roy – with his embonpoint,

he’s a man who relishes his victuals – thanks him and orders an officer to

follow him to the table of a pretty room which seems to have lost half its

furniture.

There’s an old cooked ham, a quarter of cold mutton and

sausages, two dishes of dessert, wine and liqueurs. At first, having decided to

leave in good time, I was loath to depart. But unable to resist our host’s

insistence I took my place at table opposite the eldest of them, and didn’t

lose sight of a single one of his movements. I kept an eye on him like a cat

watches a mouse, without his noticing it; because the main door of the

dining-room, which was behind him, had been left open and to all appearances I

was watching what was going on down in the courtyard. So I had one eye on him

and the other on the château’s courtyard. Beside this man sat an old tippler of

a captain of the 33rd Regiment, who got thoroughly tipsy. Next was the young

man with the little moustaches, speaking German to his neighbour. Then another

Russian, all of whose manners struck me as military. From time to time he

looked at the man sitting opposite me and smiled.’

Le Roy also notices that the number of servants waiting on

them is steadily growing. Some have moustaches, while others are bearded

peasants. His neighbour tries to reassure him by saying they’ve come bringing

more provisions in case the French would like to stay the night. At 4 p.m. Le Roy

goes down into the courtyard and orders a captain of the 17th Light Infantry –

his party, regrettably, has been taken from several regiments – to form an

advance guard with the herd and not leave the road. Vodka in great bowls has

been served to the men and by now many of them are drunk. Going back into the

dining-room, Le Roy peremptorily asks the four Russians to be so good as to

accompany him to Moscow. The poor devils seemed thunderstruck – and this

confirmed me in my idea that they all spoke French.’ He threatens to use force

if they resist. The first young man asked if he could go into the next room and

get his clothes. I consented, ordering the drunken captain to go with them.’

Now Le Roy assembles his detachment, meaning to place his

four prisoners in the middle of it, and calls up to the officers he’s left in

the dining-room to bring these gentlemen, whether they like it or not.

‘I was just about to mount my horse, when the sergeant of

the Moscow outpost came and told me he’d seen a couple of groups higher up

river, which some horsemen were fording. He was sure they were Cossacks. I was

just going to go and see, when the officers came out of the château and

approached me, laughing. They told me the Russians, having gone through several

rooms, had asked the old drunk to wait for them while they went into the little

room – saying they’d only be long enough to fetch their coats. Of course they’d

escaped by another passage that lead out of it into the garden.’

Le Roy, furious, decides to ask permission to return next

day with a battalion of his own regiment – the 85th – to search the château and

capture its occupants. Guided by the flames and smoke of Moscow ‘the

detachment, having doubled its advance guard, returns to its encampment at 9

p.m. with its herd of cattle, sheep, pigs and ponies.’

But were those four Russians newcomers who’d come to fan the

flames of an insurrection? Or were they in charge of one that’s already been

organized? He can’t be sure. ‘In either case the hidden weapons would have justified

my arresting them,’ he concludes. And the moral? ‘Always prefer a detachment

made up of men from your own company or regiment to ones supplied from

different units.’ But he’d accomplished his most important task: to get his

lowing, mooing, bleating, neighing booty back to camp before nightfall. General

Friedrichs comes and promises him a light cavalry escort and men from his own

unit to return next day and wreak vengeance on the fugitives and their château,

‘not because they’d run off, but for having assembled a

lot of men strange to the village, as well as some soldiers. If I’d let myself

be lulled by their fine promises what happened two days later to a detachment

of the 108th regiment would have happened to me.’

Luckily, next day (19 September) he’s suddenly ordered by

Davout to take his battalion to the outskirts to support the Chasseurs of the

Guard on the Kaluga road:

‘“I’m sorry, my dear Le Roy”, he said, “you can’t go back

to look for what you left behind out there either on the road or in the marsh.

Soon we shan’t have any meat, even for our sick and wounded. I’m going to send

a detachment of 300 men from the 108th under a bright and efficient captain

called Toubie.”’

Le Roy hands over the livestock to his general’s ADC,

‘keeping only two pretty little Russian horses to carry my baggage’. But Toubie

and his party aren’t sufficiently on the qui vive, and are massacred.

As the days pass, then weeks, such marauding expeditions are

having to range ever farther afield and be provided with ever heavier escorts.

Far from responding to de Lesseps’ appeal to ‘come out from the woods where

terror retains you’ and sell their ‘superfluous’ produce to market, the

peasants are (as Le Roy had suspected) forming themselves into efficient

guerrilla bands. Hardly a day goes by without at least 300 French or Allied

soldiers being snapped up by the Cossacks or by bands of guerrillas. ‘The circle

is daily being drawn tighter around us,’ a French officer writes home,’ – but

his letter too is intercepted by the Cossacks:

‘We’ve having to put 10,000 men with artillery into the

field outside Moscow to forage, and still can’t be sure of success unless we

fight. The enemy is gaining the energy we’re losing. Now audacity and

confidence are on his side.’

A despondent General Gelichet, posted at a point some forty

miles from the city, writes that every order he gets is only making him

‘want to resign my command. As for the victuals you ask

from me, the thing’s impossible. The 33rd would be helping us out if it still

had the horses killed the day before yesterday. As it is, it has only two head

of cattle left.’

Even on 30 September Césare de Laugier has written in his

diary that ‘the colonels of the Royal Guard are taking turns with the Army of

Italy’s generals of brigade to direct and command such flying columns. The good

and intrepid Colonel Moroni, the vélites’ colonel, being more than once

detailed off for this kind of job, I, by virtue of my rank, am having to go

with him.’ And goes on:

‘So yesterday about 1,000 infantrymen, 200 troopers and

two pieces of cannon were placed under Moroni’s orders, to attempt a

reconnaissance along the Tver road, as well as to protect numerous Saccomans’

[Sacs-au-mains = bagmen] bringing with them carts and pack horses. The greater

part of the villages we passed through were totally deserted, and had been

searched from top to bottom by earlier reconnaissances. Between Czerraio-Griaz

and Woskresensk, about 28 versts [20 miles] from Moscow, we’d reached the

extreme limit of our earlier excursions. In the plain a few sparse villages and

country houses which, albeit abandoned, were still completely intact and

witnessed to the sudden flight of the inhabitants. There we camped for the

night’

The Italian vélites realise that they’re in the presence of

enemy troops. But at dawn they form two columns and pursue their way without

troubling themselves:

‘And in fact the enemy withdrew as we advanced. We passed

through more villages without trouble, guaranteed as they were by the chain of

posts set up by cavalry and infantry. The heat was excessive, and a magnificent

forest spread out beyond the advanced posts to the right, where I was.

Accompanied by some NCOs, I wanted to push on that far.’

But then something surprising happens:

‘I’d only gone a few paces when I heard voices. Alone, I

walked calmly over to the side the noise was coming from. There I saw through

the trees, in the middle of the wood, a clearing where there was crowd of

people, men and women of all ages and kinds. I came a few steps closer. They

looked attentively at me, but without being either scared or surprised. Some

men, whose manners and faces didn’t augur any good to me, came toward me.’

The vélites’ adjutant-major signs to them to keep their

distance, but calls over

‘the one of them I’d recognized as one of their priests.

Then, using Latin, I asked him politely to tell me whether this was the

population of the villages just now occupied by our troops. “We are”, the pope

replied gravely, after looking closely at me, “part of the unfortunate

inhabitants of the Holy City whom you’ve reduced to the state of vagabonds, of

paupers, of desperates, whom you’ve deprived of asylum and fatherland!” As he

said this, tears ran down abundantly from his eyes. At that moment his

companions began advancing with threatening gestures. The priest managed to

calm them and ordered them back. Whereupon they remained at a certain distance,

to hear what we were saying.’

The priest says he cannot conceive what ‘barbarous genius,

what inhuman cruelty’ can have animated Napoleon to set fire to their venerable

capital. Césare de Laugier says he’s got it all wrong… No, no, says the priest.

It’s he who’s deceiving himself. There’s no question but that Napoleon was the

author of the fire:

‘While we were talking I was able to examine at my

leisure this crowd of unfortunates who were gradually coining closer to us. The

men’s masculine, energetic, bearded faces bore the impress of a deep,

ferocious, concentrated pain. The women’s air was more resigned, but it was

easy to guess what anxieties they were going through. Untroubled by my paying

so little heed to what he was saying, the pope went on with his sermon. Swept

along in some line of reasoning, he happened to touch my horse and lay his hand

on the pommel of its saddle. Seeing how moved I was, he redoubled the violence

of his words. For my part I was lamenting the fate of so many unhappy families,

women, old men, children, who, because of us, were in such a pitiful state. And

this thought made me forget the danger I was so imprudently exposing myself

to.’

Suddenly one of the Russians comes up to the ‘pope’ and,

‘with a look of sovereign scorn’ says something in his ear. Suspicious, the

Italian officer begins to walk away:

‘But then the pope asked me whether I was a Christian, a

question which only half surprised me, as I knew we’d been represented to the

Russian people as a band of heretics. The moment everyone knew I’d said I was,

I saw all the faces looking at me with greater interest, and the conversations

grew more animated. Then the pope took my hand, pressed it affectionately, and

said: “Get going as fast as you can. Ilowaiski, reinforced by the district’s

militia and some completely fresh cavalry, is advancing to attack you. By

staying here you’re exposing yourself to every danger. And do what you can to

prevent the acts of impiety your leader and your comrades are making themselves

guilty of!”’

Before going back to his men, de Laugier makes Before

going back to his men, de Laugier makes a last effort to convince the kindly

priest of his error; tells him that he and all his flock can come back to

Moscow without the least risk. But his interlocutor accompanies him to the

fringe of the forest, ‘and didn’t leave me until he saw the NCOs appear, who’d

come to look for me’.

The priest’s warning turns out to be correct. ‘A long column

of cavalry had appeared near the Liazma. Other Cossacks and armed peasants were

coming up along the Dmitrovo road.’ Some foragers are running back to the

Italian lines as fast as their legs can carry them. Many of the them, pursued

by Russian scouts, have abandoned their carts or horses, already laden with

plunder:

The Dragoons of the Royal Guard advanced. The Marienpol

Hussars made ready to receive them but, disturbed by the artillery fire, beat a

retreat, carrying away the Cossacks, who’d imprudently advanced and had exposed

themselves, not without some rather serious losses.’

By now it’s 4 p.m., too late in the day to come to grips

with this enemy. So Colonel Moroni, his foraging operation – apart from the few

carts and horses the foragers had abandoned – being completed, gives the order

to march off home:

‘But being followed closely by the enemy and forced to

escort a numerous convoy, he thought it dangerous to make the whole movement en

bloc. First the wagons and other impedimenta filed off as far as a wood to our

rear, then the troops followed in the best order.’

This is the signal for the Russians’

‘best horsemen to attack, uttering shrill cries, and

firing some shots, but without daring to come too close. Hardly was the convoy

lined up properly along the road which passes through the forest and the

sharpshooters had been placed on its flanks to protect it if attacked, than our

columns abruptly faced about, and marched against the enemy. Seeing this, the

many groups of armed peasants soon began to flee, throwing away their weapons

as they crossed the fields. The cavalry followed their example. Night was

already falling. Then two vélites rejoined the detachment. They’d got lost in

the woods while looking for me, and the pope I’d spoken with had saved them

from the hands of the Cossacks by hiding them until we’d come back.’

Not all foraging expeditions, the vélites’ adjutant-major

adds sombrely, operating under the same conditions, are being so successful.

Young Lieutenant Paul de Bourgoing, he of the fancy fur, has

to interrupt his struttings to and fro in front of the two actresses General

Delaborde has taken under his wing, and sally out with some wagons and 50 men

of his own regiment, the 5th Tirailleurs-Fusiliers of the Young Guard, to see

what he can find in a village on the left bank of the Moskova – its right bank

has already been occupied by the various Guard cavalry regiments. He’s just

entering a village dangerously close to the Russian outposts when the tocsin

sounds and a fusillade breaks out between his men and some peasants who ‘aided

by some Russian soldiers lodging with them, defend their cows and sheep’.

Seeing one of his officers and five men beat a hasty retreat, dragging a cow

with them and followed by a compact mass of peasants, he orders his men to

fire. The Russians reply with well-nourished musketry. A corporal falls wounded

in his arms, spattering him with his blood. From all sides armed peasants and

Cossacks come running or galloping across the plain. Now the whole detachment,

carrying its badly wounded corporal on a cart, has to beat a hasty retreat.

Already night is falling, and it’s necessary to find the bridge across the

river. Which they do – receiving timely support from a company of voltigeurs.

The corporal dies on the forage cart.

Altogether, such sorties are producing less and less. By the

second week in October no escort under brigade strength, or stronger, has much

chance of bringing in a convoy of foodstuffs. Baron Lejeune, struggling with

all the paperwork needed to reorganize I Corps and set it to rights, is finding

‘

‘these last days very hard. Our foragers no longer

brought us anything back, either for the men or the horses. Their accounts of

the perils they’d run were scaring, and to listen to them it seemed we were

surrounded by a network of Cossacks and armed peasants who were killing all isolated

men and from whom we ourselves would only escape with difficulty. These

perplexities made the task of restoring order as soon as possible in the army’s

organisation extremely laborious, both for the corps commanders and their

chiefs-of-staff. The days and nights were all too short to cope with so many

difficulties and I hardly had time to see anything more of Moscow than the very

long street leading from my suburb to the Kremlin.’

War Commissary Kergorre puts the matter in a nutshell:

‘Even if we had had enough provisions to spend the winter

here, we should still have had to retreat, for absolute lack of forage. What

would we have done without cavalry, without artillery, in winter quarters in

the land we’d conquered, without communication with France?’