The Wiking Division would win further laurels in the drive

to the Caucasus Mountains and then in the defensive fighting in the southern

Ukraine during the winter of 1942-1943. The spring of 1942 was a relatively

quiet time for Wiking, Steiner incorporating lessons learned from the

Barbarossa fighting. Among these was an organizational change to “Westland,”

converting it into a “light regiment” of two five-company battalions,

the fifth company acting as the heavy-weapons unit containing pioneer,

infantry-gun, and “attack” platoons.

New arrivals included a battalion of Finnish infantry and an

assault-gun battery, to replace the StuG IIIs lost in the February fighting

south of Kharkov. And in June, with only a few weeks to spare before the

opening of the new campaign, the division received its panzer battalion

(Abteilung ) under the command of Sturmbannführer Johannes Mühlenkamp. Hausser

and Steiner had long campaigned for their divisions to have a tank capability,

enabling them to act independently without help from other panzer units.

Mühlenkamp was an ideal panzer commander, combining an

aggressive attacking impulse with sound tactical knowledge. An early member of

the SS-VT, his prowess as a competition motorcycle rider led to command of

“Germania’s” motorcycle company. After recovering from wounds

suffered during the advance on Moscow, Mühlenkamp was given command of one of

the four panzer battalions being raised for the Waffen-SS (the other three

being assigned to Leibstandarte, Das Reich, and Totenkopf ).

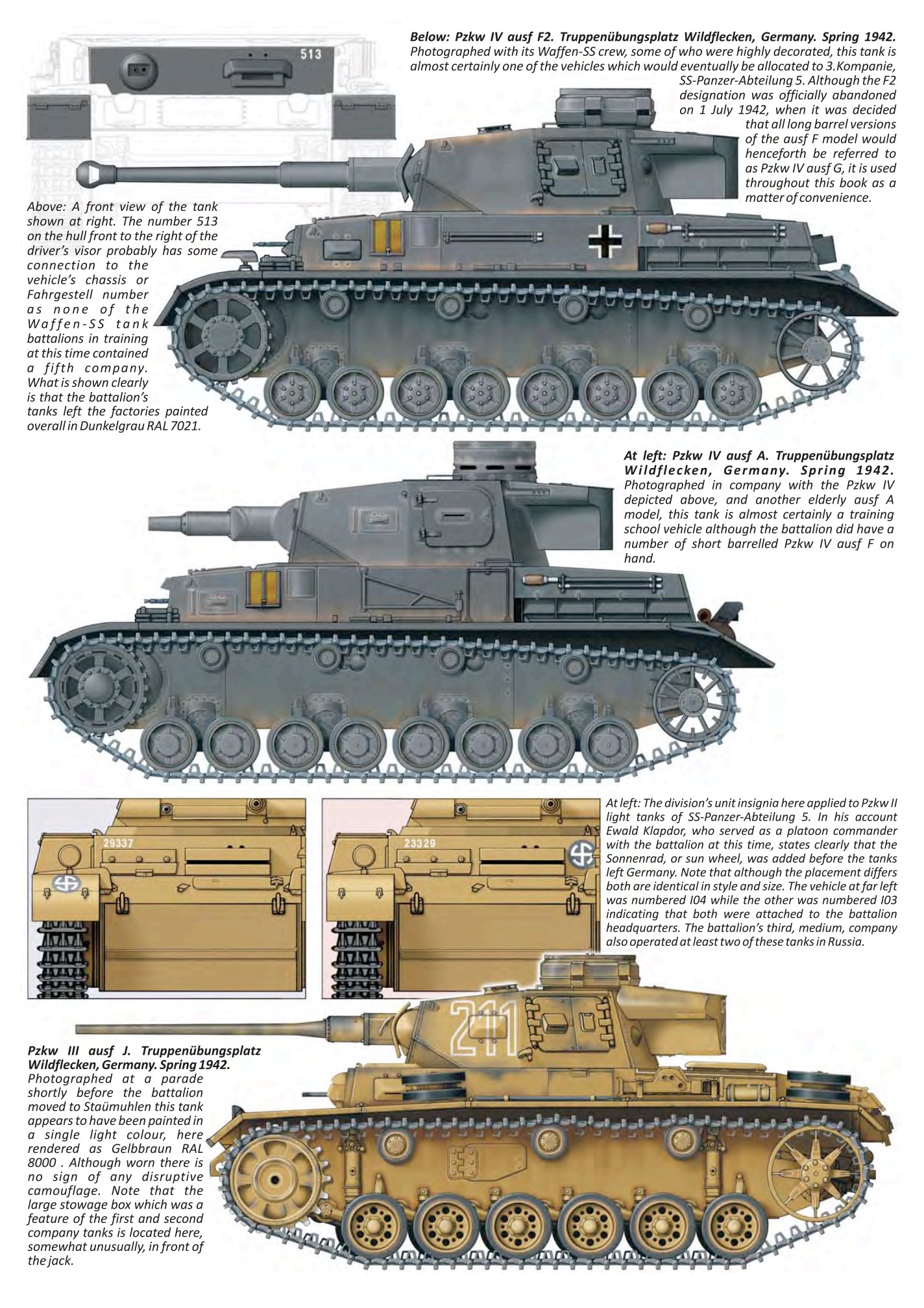

The SS tank crews were trained by the army at Wildflecken,

beginning on captured French Hotchkiss tanks before graduating to German

models. Mühlenkamp’s battalion comprised just under sixty tanks divided into

three companies. The 1st and 2nd Companies were equipped with the Panzer Mark

III, whose new high-velocity 5cm L/60 gun gave improved battlefield performance

(although still inferior to the Soviet T-34). The 3rd Company was equipped with

the Panzer Mark IV, whose original low-velocity 7.5cm L/24 gun had been

replaced by an L/43-armed model with a reasonable antiarmor capability

(subsequently upgraded with an L/48 gun).

Hitler’s 1942 summer offensive was intended to secure the

Caucasus region and provide Germany with new sources of urgently needed fuel

(and correspondingly deny them to the enemy). The attack would be directed

toward the oil fields of Maikop, Grozny, and then Baku, the ultimate prize on

the Caspian Sea. A subsidiary advance was directed toward Stalingrad to protect

the left flank of the main drive. For the offensive- code-named “Fall

Blau” (Case Blue)-Hitler had assembled approximately 1 million German and

300,000 Axis soldiers, supported by 1,900 tanks and 1,600 aircraft. This was an

impressive force, which tore through the Soviet lines with almost contemptuous

ease. Such was the success of the initial phase of the campaign, launched on 28

June 1942, that it turned Hitler’s head toward the seizure of Stalingrad. But

the attempt to capture Stalingrad would fatally divert air and ground forces

from operations in the Caucasus.

On 18 July the Wiking Division readjusted its position

slightly farther south along the River Mius Line near Taganrog. Its objective

was the recapture of Rostov, the city on the Don that Leibstandarte had been

forced to relinquish in November 1941. Steiner used an imaginative combination

of combat pioneers, infantry, and armored vehicles to break through the

concentric defensive lines that protected Rostov. Bombarded by artillery and

massed waves of aircraft, a surprised Red Army offered little resistance so

that on 24 July the city fell to the Germans. Among the wounded was the medical

officer of the pioneer battalion, Obersturmführer Josef Mengele, who had

previously been awarded the Iron Cross for rescuing two crewmen from a burning

tank. Declared unfit for further frontline service, Mengele returned to his

former interest in racial genetics, achieving lasting infamy at the Auschwitz

concentration camp.

Once past Rostov, Wiking’s orders were to cross the Kuban

River and secure the Maikop oil fields situated in the foothills of the western

Caucasus Mountains. The tanks, assault guns, artillery, and truck-borne

infantry raised huge plumes of dust as they raced southward. The divisional

history reported how its troops “drove through the masses of still

retreating Russians who scattered before the panzers and disappeared in the fields

of sunflowers.” The changing landscape also seemed to reflect Germany’s

improved military fortunes:

The villages were prettier than in the Ukraine, the roads

better and countryside was covered with golden corn and red tomato fields. In

the village gardens the trees were heavy with ripening fruit. Everything the

heart desired was there: melons of a size never seen before, apples, pears and

other delicious fruit which made the soldiers’ mouths water. Every pause was

used to gorge on the fruit and quench their thirst. It was very hot and dusty;

so dusty that the only feature recognizable through the thick layer of dust on

the faces of the young European volunteers were their eyes.

The progress of the German land forces was facilitated by

the close air support provided by Colonel General Wolfram von Richthofen’s

Luftflotte Four. Richthofen-a cousin of the World War I fighter ace-was an

intelligent, uncompromising airman who had pioneered air-ground cooperation.

The Luftwaffe’s contribution to the campaign was readily acknowledged by the

Wiking officers: “Soon it became customary for the Luftwaffe commander,

Major Diering, to land at dawn at the command post by Storch [light aircraft].

He would take part in the briefing and issue orders to his liaison officer

accordingly. As the Panzerkampfgruppe deployed it would be accompanied by an

air patrol of two ground-support aircraft. These would call up the remainder of

the unit’s aircraft, which were on alert at Rostov, when heavier air support

became necessary.” This period marked the high point of German air-ground

cooperation, soon to be undermined by a chronic shortage of aircraft and

aircrew as Hitler’s demands stretched the Luftwaffe beyond breaking point.

The physical barrier of the Kuban River was crossed in

stages between 4 and 7 August. This opened the way for a direct advance on the

oil fields around Maikop, occupied by German troops on the tenth. A team of oil

specialists had been sent to restore the wells to production, but the

retreating Soviet forces had destroyed the plant facilities so thoroughly that

no oil was ever extracted.

As Wiking advanced south of Maikop, it entered the foothills

of the Caucasus, whose narrow defiles and high passes impeded operations. The

division was ordered to halt and await the arrival of German mountain infantry.

Wiking’s last offensive action in this region was fought on 14 August, when its

Finnish battalion scattered the remnants of a Red Army cavalry division during

the capture of Linejuaja.

For the rest of August and into September Wiking took part

in antipartisan operations against Soviet forces hiding in the hills. During

this period the army-organized Walloon Legion (Legion Wallonie) from southern

Belgium briefly came under Wiking control. Among the legion’s soldiers was

Belgian journalist and nationalist politician Léon Degrelle, who was greatly

impressed by the SS division. He would later use his influence to have the

Belgian unit taken over by the Waffen-SS. When the German mountain troops

arrived, they joined the Walloon Legion to drive through the mountains and

capture the Black Sea port of Tuapse.

At one point-as the men of the Wiking Division awaited

redeployment-they were entertained by a regimental orchestra, which set up its

instruments a short distance from the front line. Sturmann Hepp, a Dutch

soldier in “Germania,” found the concert-which included uplifting

works by Beethoven and Wagner-a deeply moving experience. It confirmed his

belief in the moral, spiritual, and intellectual superiority of the New Order:

“How characteristic for the humanity and culture we were defending that it

was not some fiery dance music, some libidinally charged dance hall tune that

was brought to the men at the fighting front. Instead it was the most sublime

and challenging music that the occidental masters had created.”

#

Orders from OKH for Wiking’s redeployment to the Chechen

region of the East Caucasus were instigated on 16 September. The transfer took

four days and saw the division assigned to Kleist’s First Panzer Army, now bogged

down in the Terek Valley around Mosdok.

When the chief of staff of the First Panzer Army explained

the objectives to Steiner- a march on Grozny to be followed by a crossing of

the Caucasus Mountains to strike Baku-the SS general was openly skeptical of

the whole enterprise, especially given the Germans’ limited resources and the

lateness of the campaigning season. The chief of staff agreed with Steiner’s

misgivings but emphasized that these were orders from OKH and were to be

obeyed. This disjuncture between Hitler and his staff and the generals at the

front would become ever greater, directly contributing to the failure of the

campaign.

The Wiking Division was assigned to General Eugen Ott’s LII

Army Corps, whose drive from Mosdok had been stopped in its tracks. Ott’s

high-handed manner immediately caused friction with the bullish Steiner, and

relations between the two commanders deteriorated as the campaign progressed.

Blocking any German advance to Grozny was the Malgobek

ridge. A frontal attack had already been repulsed with heavy casualties.

Steiner was ordered to launch a flanking maneuver along the valley of the River

Kurp that ran behind the ridge. Wiking’s first objective was the fortified town

of Ssagopschin, several miles farther up the valley, which was crisscrossed

with steep-sided gorges (balkas) and antitank ditches. Steiner expected close

air support to help him rip open the Soviet defenses, but Richthofen flew in to

LII Corps HQ to inform him that the Tuapse and Stalingrad operations had

priority and all he could provide were a few obsolete bombers.

The troops moved into position on 26 September, ready for

the assault on the following day. The plan of attack was for the infantry from

“Westland” and “Nordland” to secure the higher ground running

on both sides of the valley, while the tank battalion and assault-gun battery

would advance along the valley floor, reinforced by combat pioneers and

infantry mounted on the armored vehicles. Fire support would be provided by the

massed batteries of the Wiking artillery regiment and LII Corps.

To Steiner’s dismay, the enemy defenses were harder to

overcome than even he had anticipated. The well-supplied Soviet troops fought

with the utmost resolve, while the German armored advance was slowed by minefields

and Soviet tank-hunter teams who raced up to attack the panzers with bundled

charges. On 28 September the Germans made better progress and were within

reaching distance of Ssagopschin until a Soviet counterattack forced the SS

infantry to temporarily retreat.

The Wiking troops not only faced concentrated artillery and

machine-gun fire but were continually bombed and strafed by Soviet aircraft

roaming over the battlefield at will. The infantrymen crouching under their

fire noticed that many were from the United States, transported overland

through Iran to the Soviet Caucasus command. They also found themselves under

attack from British-made Valentine tanks, an otherwise reliable and

well-armored vehicle undermined by a woefully inadequate 2-pounder (40mm) main

gun.

The Wiking armored vehicles managed to repel the Soviet

counterattacks but were unable to break through to Ssagopschin. All the while

they were subject to a Soviet barrage from the heights on both sides of the

valley. Sturmmann Neumann, a tank crewman in a Panzer Mark III, recalled coming

under this heavy artillery fire:

We were being engaged from all sides. The reports from an

15.2cm battery could be clearly distinguished. It was a damned tricky

situation. The bastards were registering on us. The impacts came ever closer.

Depending on where they landed we moved back and forth. The shells exploding

right next to our tanks made an ear-deafening racket. In between, there was the

whistling sounds of the anti-tank guns and the tank main guns. Dust and dirt

penetrated the interiors of the tanks; shrapnel smacked with a clang against

the steel walls of the tank. It was a terrible strain on the nerves, sitting

there in the middle of artillery fire without being able to do anything,

hearing the report of the guns and waiting for the impacts. There was no

getting around the feeling of confinement in a tank.

Neumann and his comrades were eventually able to escape

their ordeal after withdrawing into a nearby tank ditch.

Despite the best efforts of the Wiking Division, there was

no escaping the fact that the advance had been halted. Kleist and Ott pressured

Steiner to capture Ssagopschin without delay. Steiner also encouraged his men

to press forward, but another attack on 30 September similarly failed to make

headway. On 1 October Oberführer Fritz von Scholz, commander of

“Nordland,” insisted his troops could not advance farther and asked

to be allowed to withdraw to a better position more than a mile to the rear.

Ott expressly forbade any retreat, but Steiner, on discussing the situation

with Scholz at the front, overruled the order and allowed the SS troops to

retire. This proved a wise decision, enabling the now disordered SS units time

and space to reorganize for further offensive action.

At dawn on 2 October the combined forces of the division

advanced at speed, overrunning the Soviet positions and finally capturing

Ssagopschin. Despite the success, criticism of Wiking continued, with First

Panzer Army headquarters suggesting that its multinational nature caused

problems of command and control. This accusation was vehemently refuted by the

division, which pointed out that on 1 October 1942 foreign volunteers made up

around 12 percent of the division’s regulation strength and that combat had

melded the various nationalities into a coherent whole.

Ott, still furious that his orders had been disobeyed,

instructed Steiner to capture the Malgobek ridge, now in an exposed position

following the fall of Ssagopschin. The “Germania” Regiment was chosen

to lead the attack. Steiner, on being told that again there would be no air

support, lost his temper and shouted at Ott that “the attack could not be

executed and that he would report the matter to Reichsführer-SS Himmler.”

This threatened circumvention of the chain of command was clearly a breach of

regulations, and Steiner was duly reprimanded by First Panzer Army

Headquarters. But Steiner’s foot-stamping did have one desired result: a flight

of Stukas was promised for the attack.

“Germania” opened the assault on 5 October,

supported by the rest of the Wiking Division from the south and by army units

from the north. The SS troops secured a foothold on the ridge, which was

cleared with comparative ease on the following day. The Red Army withdrew

farther east to continue its defense of Grozny. Ott then insisted that the

nearby Hill 701 be secured by Wiking and the army’s 111th Division.

Both divisional commanders expressed reluctance to continue

the offensive, which brought forth a sarcastic response from Ott: “If the

authority or willingness to fight on the part of subordinate leaders is not

sufficient, I request the esteemed division commanders to personally take the

place of the regimental commanders and conduct it.” The first assault on

the position was made on 15 October, and after a series of hard-fought seesaw

battles Hill 701 was captured by the Finnish battalion on the sixteenth.

Steiner’s reluctance to press forward had been informed by

his firsthand knowledge of the growing weakness of the German forces in the

area; any advance on Grozny without huge reinforcement was clearly impossible.

In fact, the capture of Hill 701 marked the high-water mark of the German

advance in the Caucasus; from this time onward, they would go over to the

defensive.

Arguments between Waffen-SS field commanders and their army

counterparts were extremely rare-normally confined to Theodor Eicke’s splenetic

outbursts-but the ongoing dispute between Steiner and First Panzer Army caused

disquiet at OKH. On 20 October General Kurt Zeitzler-Halder’s replacement as

army chief of staff-flew out to the Caucasus to assess the situation. Steiner’s

reservations about his division’s treatment were seemingly accepted by

Zeitzler, who also tried to allay anxieties as to the overall strategic situation.

In early November Wiking was withdrawn from the Malgobek

area and redeployed a few miles away in defense of German positions around

Alagir. During this period of relative calm, Steiner was informed that the

division would henceforth be designated as 5th SS Panzergrenadier Division

Wiking, in line with a comprehensive numerical overhaul of all Waffen-SS

formations. (Each unit in the division was prefixed by its formation number,

except for the two panzergrenadier regiments, which were all numbered sequentially,

with Leibstandarte’s two regiments numbered 1st and 2nd, Das Reich’s numbered

3rd and 4th, and so on, with Wiking’s two regiments numbered 9th and 10th.)

Of rather more significance was the troubling news that a

Soviet offensive had trapped the German Sixth Army in Stalingrad and was

threatening to cut off Army Group A in the Caucasus. On 22 December Wiking was

ordered to drive northward to help the Fourth Panzer Army’s attempt to break

through to Stalingrad. This was the first stage in a wider German retreat from

the entire Caucasus region.

After a relatively swift train transport north, advance

elements of the division detrained on 30 December at a snowbound Simovniki,

headquarters of Fourth Panzer Army. But on arrival the SS troops found the town

deserted, the headquarters recently departed. Steiner was informed that Wiking

was not to take part in a rescue attempt toward Stalingrad-now abandoned-but

act as a rear guard for a general retreat back to Rostov. “Westland,”

supported by a battalion from “Germania” and 5th Panzer Battalion,

held Simovniki for seven days, buying vital time for the withdrawal, not only

for the rest of the division but also for Kleist’s First Panzer Army, hurrying

back to a new defensive line behind the River Don.

The harsh winter weather gave Wiking’s withdrawal a

nightmarish quality. The tank drivers-inexperienced in these conditions-found

travel across the icy balkas a constant challenge; on such steep gradients, the

caterpillar tracks could not always find sufficient traction, so the tank

slithered back to the bottom of the ditch, entailing a long-drawn-out rescue

process with other tanks acting as towing vehicles. On one occasion, three

Panzer IIIs had to be abandoned due to the ice-ridden conditions.

All the while, the retreating German troops faced the

possibility of attack by packs of roving T-34s. Red Army units harried the

retreating Wiking rear guards, but they lacked sufficient numbers to bring them

to battle. By the beginning of February, Wiking approached Rostov with the

major part of the First Panzer Army safely across the Don. On 5 February the

battered division passed through the city to take up new defensive positions

around Stalino (Donetsk). Once in place, Wiking was ordered to surrender its

“Nordland” regiment, which would become the core infantry unit in a

new Waffen-SS formation, the 11th SS Volunteer Panzergrenadier Division

Nordland, with Scholz as its commander. A battalion of Estonian troops was sent

to join Wiking as partial recompense for the loss of “Nordland.”

Hitler’s 1942 summer offensive had ended in calamitous

failure. The Wehrmacht was back in the same position it had occupied in July

1942, but now there were huge gaps in the German line across the Ukraine, which

the mechanized divisions of the Red Army were intending to exploit.