Koguryo, a nation based in northern Korea, rose to power during the first several centuries ad, emerging dominant from a struggle with other Korean nations to its south, China to its west, and nomadic peoples to its north. It reached its peak under King Gwanggaeto and King Jangsu, who moved the capital from Kungnaesong (T’ungkou) to Pyongyang. Gwanggaeto. According to his own propaganda, he conquered sixty-four fortresses and 1,400 towns. He seized the Liaotung Peninsula, occupied by China, Sushen nomad-occupied Manchuria in the northwest, and Paekche as far as the Han River to the south.

King Gwanggaeto The Great

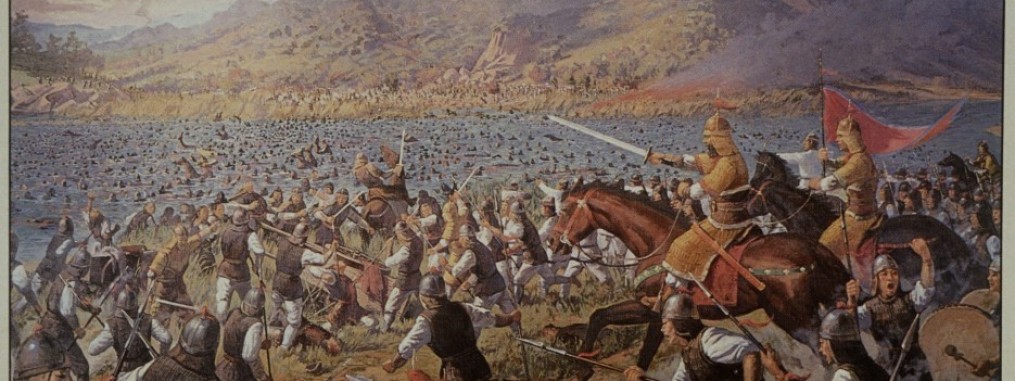

The second Sui emperor, Emperor Yang, was determined to bring the northeast frontier under control and to match the achievements of the Han by controlling all the lands that were once part of the Han Empire, including Liaodong and northern Korea. But Koguryo was an obstacle to resurgent Chinese expansionary plans, and Yang directed his attention at subjugating the northern Korean state. In 612, after an unsuccessful naval attack, he embarked upon a major campaign against Koguryo. This was a large-scale undertaking that involved forces and resources from across the Chinese Empire. A confident Emperor Yang, fresh from successful campaigns against the Turks, sent a reported 1,130,000 men 1,000 li into Koguryo. About 300,000 troops were detached from the main force and unsuccessfully besieged P’yongyang. On their return, they were ambushed by Koguryo general Ulchi Mundok at the Salsu (Ch’ongch’on) River, a defeat that only 2,700 Chinese forces are reported to have survived. The size of the forces and the magnitude of the defeat were recorded by Tang China historians, who no doubt inflated these figures to discredit their Sui predecessors. Nonetheless, Koguryo won an impressive victory that became part of Korean legend. Ulchi Mundok later became a symbol of national resistance for modern Koreans. Emperor Yang made two more unsuccessful attempts on Koguryo in 613 and 614, and those costly defeats were a major factor in the collapse of the Sui and the rise of the Tang.

The newly established Tang dynasty (618-907), one of the

most brilliant in Chinese history, inherited the same foreign policy objectives

of its predecessors-to secure the northern frontier and bring all the former

Han lands under its control. When in 628 the Tang defeated the Turks, it began

to reconsider Silla’s appeals for assistance. Silla, seeing an opportunity to

deal a fatal blow to its northern rival, justified its need for Chinese

intervention in much the same way that Han chieftains may have called for Han

help in overcoming Wiman’s Choson blockade of the overland route to China. Tang

emperor Taizong (r. 626-649) attacked Koguryo and was defeated at Ansi Fortress

by Koguryo general Yang Man-ch’un. Taizong was again defeated in 648, and his

successor, Tang Gaozong (r. 649-683), launched unsuccessful attacks in 655 and

in 658-659. Koguryo?’s consistent success against the world’s mightiest

military force was an impressive achievement in Korean annals. It also shielded

the states of Paekche and Silla from the brunt of Chinese expansionism,

allowing them time for autonomous development.

In 645, Emperor Taizong invaded. He managed a victory at

Liaotung, but failed to capture the minor fortress at Anshi (Yingchengtzu),

despite a sixty-day siege with up to seven assaults a day. When winter began to

descend, Taizong retreated; his second attempt, in 647, also failed.

Defying the Chinese

Not until 668, when the remarkable Empress Wuhou ruled the

empire (in fact, if not in name) did China finally succeed in conquering

Koguryo, thanks to an alliance with the Silla kingdom. Despite its eventual

fall, Koguryo’s defiance of the invading Chinese remains a source of great

significance and pride for Koreans today-as does Silla’s unification of the

Korean peninsula, pushing out the Tang in 676.

Sino-Korean War (610-614)

In the period corresponding to the early Middle Ages in

Europe, Korea was divided into three separate kingdoms. The two northern

kingdoms, Koguryo and Paekche, had been vassals of China, and by the seventh

century, although now independent, they still retained close ties with that

larger realm. Sui-dynasty Chinese emperor Yangdi (Yang-ti; 569-618) attempted

to reestablish the former relation of vassalage, demanding that the Korean king

of Koguryo acknowledge Yangdi as overlord. When the Korean king refused, the

Chinese emperor ordered an invasion. Twice the Chinese invaded, only to be

repulsed by fierce Korean resistance. The emperor personally led a third

invasion force, which made excellent progress. However, at the point of

consummating his conquest, Yangdi was informed of a rebellion in China, at

Loyang, his capital city. He had no choice but to break off the invasion and

raise the siege against his capital. He lost control of the situation, however,

and was forced to flee for his life to southern China. All thought of Korean

conquest fled with him. The emperor was subsequently killed in exile.

Sino-Korean War (645-647)

Three decades after Emperor Yangdi (Yang-ti; 569-618)

attempted to reestablish northern Korea as a vassal of China in the SINO-KOREAN

WAR (610-614), Emperor Taizong (T’ai Tsung; 598-649) of the Tang dynasty invaded

the Korean Peninsula, again in an effort to expand the Chinese empire. Like

Yangdi, Taizong concentrated on the northern kingdom of Koguryo. His armies

succeeded in capturing several cities, but unyielding Korean resistance,

combined with the harsh winter of the north, sent Taizong packing in 645. He

did not renew his campaign of invasion in earnest until 647 but once again was

driven out of Koguryo.

Sino-Korean War (660-668)

The northern kingdoms were conquered, resulting in the

enlargement of Silla and the acquisition by China of most of Koguryo, a

long-sought-after prize.

Koguryo and Paekche, the two kingdoms making up the northern

part of the Korean Peninsula, entered into an alliance to attack Silla, the

kingdom of south Korea. In response, Silla called on Gao Zong (Kao Tsung;

628-683), emperor of China, for military aid. China had repeatedly attempted

conquest in Korea, without success, so the appeal for aid seemed to Gao Zong a

great opportunity. The emperor dispatched a large Chinese army via Manchuria

into Koguryo, while a Chinese fleet struck Paekche along its coast. Japan

entered the war during 662-63 on behalf of Paekche, but its land and sea forces

proved inadequate and were defeated. The Japanese navy incurred the greatest

losses; it was almost totally destroyed. As a result of Chinese intervention,

Paekche was conquered and incorporated into Silla, which became a Chinese

vassal state. Farther north, however, Koguryo continued to resist. At last, in

668, combined Chinese and Sillan forces captured the north’s capital city, and

Koguryo yielded. Silla acquired all of the area south of the Taedong River,

whereas the greater part of Koguryo was annexed to China.

Further reading: Woodbridge Bingham, The Founding of

the T’ang Dynasty: The Fall of Sui and Rise of T’ang (New York: Octagon Books,

1970); Yihong Pan, Son of Heaven and Heavenly Qaghan: Sui-Tang China and Its

Neighbors (Bellingham, Wash.: Center for East Asian Studies, Western Washington

University, 1997).

THE UNIFICATION OF KOREA UNDER SILLA

In 660, the Tang, frustrated by their inability to overcome

Koguryo resistance, decided on a plan to invade Paekche by sea, and after

subduing Paekche, to invade Koguryo from the south. This plan was implemented,

with Admiral Su Dingfang, who had recently defeated the Turks, leading the

Chinese forces. His ships sailed up the Kum River while Silla forces under

General Kim Yu-sin crossed the Sobaek range that separates the Kyongsang

heartland of Silla from the Cholla and Ch’ungch’o? ng regions of Paekche. On

the Hwangsan Plain, the Paekche forces under General Kyebaek were defeated.

Paekche king Uija surrendered at Ungjin, and in the seventh lunar month of 660

the Tang forces were in control of most of Paekche.

Tang now concentrated on its major goal of destroying

Koguryo. In 668, Tang land and naval forces, and Silla forces under Kim In-mun,

captured P’yongyang. As a result, Koguryo fell. It was clear that Tang efforts

were now aimed at directly controlling the entire Korean peninsula, with the

former Koguryo and Paekche territories to be directly incorporated into the

empire and Silla to survive only as a satellite state. The Chinese emperor

proposed that Silla become the Great Commandery of Kyerim-in essence a Chinese

territory-and offered to appoint the Silla king as its head. The Silla monarch

Munmu (r. 661-681) rejected the offer and instead invaded the

Chinese-controlled territory in Paekche. Sillan forces drove out the Chinese by

671, and then moved north into Koguryo. In a series of battles in the Han River

basin in 676 Silla forced the Tang into retreat, gaining control of all the

territory south of the Taedong River, that is, almost all of peninsular Korea.

Although Chinese and Korean accounts of this period vary, it is clear that

Silla emerged as the victor. Most of the peninsula was now under Silla’s

control. The Korean peninsula, and Silla especially, proved too much of a

logistical problem for permanent occupation by China. China had a hard time

supplying its troops in the peninsula. Silla had provided its Chinese forces

with food. Once Silla turned against them the logistical problems proved too

much for the Chinese, contributing to their defeat and withdrawal. Tang settled

for the destruction of a strong Koguryo contiguous to its northeast frontier

and ceased further efforts to intervene militarily in the peninsula. To further

secure their frontier, the Chinese set up a small puppet state of Lesser Kogury

in the Liaodong region of Manchuria.

Silla’s victory in unifying most of the peninsula can be

attributed to several factors. The political and military institutions of the

kingdom proved capable of providing a stable and effective government that

could successfully carry the country’s expansion. The kingdom itself enjoyed

considerable prosperity and had an economic base and a system of extracting the

surplus from that base sufficient to support large military undertakings.

Nonetheless, it is not certain that this was any less the case with its rivals.

Most probably it was geography that provided the greatest opportunities for the

kingdom. Koguryo had to wage wars on its northwestern and southern boundaries,

and Paekche was vulnerable to Koguryo to the north, Silla to the south, and

China from the sea. Silla in the southeast corner of Korea, however, had easier

boundaries to defend and was out of reach of direct assault by China. China

assisted in the unification, but unintentionally, since its motive was to

establish control over Korea, not to create a strong united state there.

The unification of most of the peninsula by Silla in 676 was

a pivotal event in Korean history. From the late seventh century to the

twentieth, a single state dominated the peninsula, including most of the

agricultural heartland of what was to become Korea. Gradually, within the

framework of the peninsular state, a culturally well-defined and ethnically

homogeneous Korean society emerged. This process, however, was only beginning

in the seventh century.