Despite the bombing and total destruction of Cassino town by

the Strategic Air Forces, on the evening of 19 March the Allies were forced to

called off their third attempt to break through the Gustav Line. In five days

the New Zealand and Indian Divisions had lost nearly 5,000 men. All immediate

offensive plans were shelved. What was achieved in return for a heavy loss of

life and casualties? Three incursions made in the Gustav Line seemed a paltry

reward. A small bridgehead across the downstream Garigliano had been

established, about half of Cassino town and Castle Hill captured, and in the

east the Americans and French at great cost had taken more mountains.

While the end of the third battle for Cassino seemed to have

little meaning, in the air the DAF [Desert Air Force] continued its incessant

fight to keep the Luftwaffe subjugated and to provide close support to Eighth

Army. Towards the end of March 1944, DAF’s AOC-in-C, AVM Broadhurst, who had

led them from the deserts of North Africa to Italy’s Apennine mountains,

departed to be replaced by AVM Dickson. Exactly one year before, at El Hamma in

Tunisia, Broadhurst had pioneered DAF’s innovative use of fighter-bombers in

close support of a decisive breakthrough on the ground. He also had ensured

that, despite the massive growth of Allied air forces in diverse roles, DAF

retained its powerful and unique identity.

At the time of DAF’s operation at El Hamma in Tunisia,

Dickson had been making an inspection visit of DAF with Air Marshal

Leigh-Mallory, AOC-in-C Fighter Command. They returned to the UK armed with

lessons learned from DAF’s organization and tactics, which were put to good use

in the air support planning for the Normandy invasion. Not least of these were

the DAF operations using fighter-bombers. Modification of fighters for the

fighter-bomber role had first been developed in the Western Desert in March

1942 when the Luftwaffe had some ascendancy over DAF.

In his Tunisian visit Dickson must have been impressed with

what he saw and learned of DAF’s close support tactics for Eighth Army, for on

taking up his new command of DAF in late March 1944, Dickson ordered more and

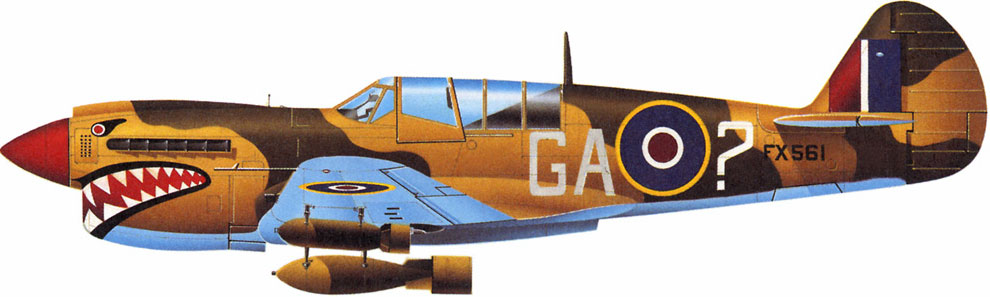

more conversions of fighters to this role. Into April and May in support of

ground forces at Anzio and Cassino, Kittyhawks carried a 1,000lb bomb under the

aircraft’s belly, and two 500lb bombs under the wings. Mustangs and

Thunderbolts also carried 1,000-pounders, and even Spitfires a 500-pounder in

‘Spitbomber’ mode.

The Rover David Cab-rank system was intensified to bring

even closer support on the battlefield. As well as the Mobile Operations Room

Unit (MORU) named David, in recognition of its introduction by Group Captain

David Haysom, five more MORU Rovers were established, Paddy, Jack, Joe, Tom and

Frank. Each MORU would normally have an RAF officer in command, and preferably

one who had some army experience. Around eighteen Eighth Army men in a MORU

would include two officers, a sergeant, a radio operator, a cipher clerk,

technicians, drivers, mechanics, a cook and guard troops. Their vehicles and

equipment, typically comprising an armoured car and trailer, a light truck, and

three jeeps with trailers, gave them a high degree of self-sufficiency.

Some fighter-bombers ranged farther afield in modified air

interdiction operations. Rather than targeting infrastructure concentration

points, strikes were re-focused against bridges and the movement of the enemy’s

road and rail traffic. To raid rail routes and traffic deep behind and to the

north of the Germans’ right flank at Anzio, on 31 March the 57th Fighter Group

USAAF relocated its fighter squadrons of P-47 Thunderbolts to Alto near the

port of Bastia on Corsica’s east coast. Flying across the Tyrrhenian Sea, their

priority targets would be railway locomotives, rolling stock and road traffic

in northern Italy. The squadrons were set a target of forty-eight sorties a

day, and within two weeks were averaging eighty a day.

While at Alto they began to be armed with eight- to

eleven-second fuses for 500lb and 1,000lb high-explosive bombs. The delayed

fuses led them to begin dropping their bombs from below 500 feet so as to

achieve more direct hits on the railway tracks. This prompted their Major Dick

Hunziker to form a flight of ‘Tunnel Busters’, led by Captain Lyle H. Duba. The

tactic was to skip-bomb the railway tunnels, where it was thought trains used

to hide out in daylight. Duba believed that he and three other pilots of the

‘Tunnel Busters’ Flight caught several locomotives and trains hiding out in the

tunnels:

We flew at least 20 of these hair-raising missions on the

deck, strafing the target, dropping a single bomb and then immediately going

into a high-G pull out to avoid the ridge the tunnel went through. On several

occasions the bomb exited the other end of the tunnel before exploding, but

most of the time it detonated inside.

Hunziker was of the view that, even if there was no train in

the tunnel, the underground track and tunnel structure would have been severely

damaged.

In anticipation of the Allies’ build-up for spring

offensives at Anzio and Cassino, the Luftwaffe garnered its remaining numbers

to try and blunt Allied air attacks. However, air superiority and many more

fighter squadrons gave DAF a lethal tactical advantage. Rather than being drawn

into individual dog-fights, they were able to shift to an emphasis on formation

group work.

While the resourcing of air forces in UK to support the

Normandy landings attracted the latest types of aircraft, DAF was left to persist

with many outdated models such as Baltimores, Bostons and Kittyhawks. This was

only viable because of the Allied air forces’ superiority over the Luftwaffe’s

meagre strength in Italy. Bari may have had far-reaching consequences for the

Italian campaign but, day in day out, Allied air power still continued to

dominate the skies.

#

To achieve a decisive advantage on the ground, General

Alexander planned a build-up with a number of deceptions. The vast bulk of

Eighth Army was gradually moved at night time from the Adriatic coast to the

Cassino front. False information on planning for another seaborne landing

north-west of Rome at its port of Civitavecchia was leaked to the Germans. It

must have had an effect, for Kesselring kept strong reserves north of Rome

until a few days after the start of Eighth Army’s Operation HONKER, the next

attack on Cassino and the Gustav Line.

The Canadian Corps of two divisions was brought into Eighth

Army reserve without announcement. At the same time fictitious information was

issued which indicated that the Canadians were relocating to Naples to embark

for the fake amphibious operation to land at Civitavecchia.

The Allies’ overwhelming air superiority reduced

reconnaissance by the Luftwaffe to a minimum, strengthening the cloak of

secrecy. The concealment of forces was not just to give the benefit of

surprise, it would hide the reserve capability to exploit the capture of

Cassino and Monte Cassino, so as to surge forward up the Liri Valley in

Operation DIADEM, to combine with an Anzio breakout – codenamed Operation

BUFFALO.

However, with the weather improving, and recognizing the

inevitability that the Allies must be rebuilding for a new offensive, the

Germans began to throw their remaining air power into some large air battles.

Despite the priorities of the war in north-west Europe, some

newer model aircraft did keep feeding through to DAF. In mid-March Squadron

Leader Neville Duke, the leading Spitfire ace in the Mediterranean, returned

from his sojourn as a training instructor, and took over as commander of No.

145 Squadron RAF. Soon after his arrival he was delighted to take possession of

a new Spitfire Mk VIII. In this new Spitfire, on 24 March, Duke led two patrol

operations of 145 Squadron. On one patrol they engaged in a battle with more

than thirty Luftwaffe fighters. The result was five more victories to take 145

Squadron’s overall score above 200.

Duke had brought with him to 145 Squadron Australian Flight

Lieutenant Rod McKenzie, who for a period had been a fellow training instructor

in Egypt. On one of those training days Duke had asked McKenzie to fly with

him. He accepted only on condition that he could fly a Spitfire, and if Duke

promised to get him a transfer to a Spitfire squadron.6 In a fateful decision Duke

found a way to fulfil his promise

Ensuring that experienced pilots spent time away from

operations on training instruction duties, was a further strength of the Allied

air forces. The Luftwaffe’s loss rates were too high for them to effectively

allocate sufficient experienced pilots to training. The result was that new

pilots in Luftwaffe squadrons were thrown into combat without experienced

pilots to pass on their knowledge and guide them. It seriously shortened their

survival rates, but on both sides a victory could be quickly followed by a

defeat and death.

On 27 March Canadian Bill Downer of No. 93 Squadron RAF shot

down two Fw190s to become an ace. A couple of weeks later, in a patrol off

Anzio, Downer misjudged his height, crashed into the sea and was killed. His

fellow pilot, Australian Warrant Officer Bobby Bunting, who had shot down two

Fw190s on 29 February over Cisterna for his first victories, had a lucky

escape. Outnumbered in a dogfight over Cassino, his Spitfire was hit. Wounded in

the right leg, Bunting somehow got away to return safely to base.

Another Australian, Squadron Leader Bobby Gibbes of No. 3

Squadron RAAF, one of Australia’s most distinguished fighter aces and leaders,

spoke of his innermost feelings in air fighting:

In that one minute the air is full of twisting, turning,

frantic aeroplanes, and the next minute not a single enemy machine can be seen.

The enemy has completely disappeared. You then collect the remnants of your

squadron, count them hastily, then the fires burning below. The feeling is a

strange one. Some of those fires down below contain the mutilated bodies of

your friends. But as you look down, you have no real feeling other than, I hate

to confess, probably terrific relief that it is them and not you.

It must be the animal in us really I suppose, and the

strong spirit of self-survival which has become uppermost. Man becomes animal

when he thinks he is about to die. As you fly back to your base, now safe at

last, a feeling of light-hearted exuberance comes over you. It is wonderful to

be still alive and it is, I think, merely the after-effect of violent, terrible

fear. I am not afraid to confess to being frightened. I was almost always

terrified.

On landing back, you look for your squadron aeroplanes at

the dispersal sites, and if your friends’ aeroplanes are there, your heart

fills with gladness for you have become a caring human being again.

He thought it often seemed to be an interminable wait for

other missing aircraft. Then when the elapsed time appeared to be too long, an

aircraft approached and touched down, ‘You look eagerly for its identifying

letters, hoping against hope that it is one of the missing, returning’.

Engagements were often very brief, and always violent, but

could be interspersed with interludes of uneventful operations. The dogfights

and victories were statistics which belied the massive number of sorties flown.

Many operations were completed without any engagement with enemy aircraft, or

only a fleeting contact, with no claimed kills. On 29 March, over Anzio, Pilot

Officer Doyle of No. 417 Squadron RAF claimed his first victory, a Bf109.

Despite then being attacked, wounded and his Spitfire catching fire, he

probably also downed an Fw190. Doyle managed amazingly to crash-land in the Nettuno

beachhead and survive. His first victory had come on his 185th sortie.

#

In early March Group Captain Hugh Dundas was awarded the

DSO, and informed by AVM Broadhurst in confidence that, if he wanted to get

back into operations, he was to be appointed commander of the renowned No. 239

Wing RAF. At the same time as feeling very flattered, Dundas was very

apprehensive. The battle-hardened 239 Wing included the formidable Nos 3 and

450 Squadrons RAAF. It was the largest wing in the Mediterranean theatre, and

was looked upon by nearly everyone as the best formation operating in the

fighter-bomber role. Dundas himself, just twenty-three years old, thought it a

staggering promotion, and also daunting:

It was the question which I had been both dreading and

hoping for. The old struggle was raging within me – the struggle between the

knowledge that I should fight on and the desire to call it a day and stay

alive.

Furthermore, Dundas knew really nothing about the skills

of flying fighter-bomber roles and dropping bombs. He knew he would have to

learn new flying techniques, and regularly lead the wing on operations. Whereas

in fighter dog-fights you pitted your plane and ability in one-on-one contests,

as a fighter-bomber you had to dive into heavy flak, and a random but increased

risk of being shot down. Dundas told Broadhurst that he would take the job.

It was soon after this meeting that Broadhurst was

transferred back to the UK, to command the air forces for the D Day invasion,

before Dundas’ promotion was approved. The new AVM Dickson chose the Australian

Brian Eaton, commander of No. 3 Squadron RAAF, to be commander of 239 Wing.

Dundas had great respect for Eaton and, despite missing out on promotion, still

found himself wanting to get back into operations. At the beginning of May he

persuaded Dickson to let him join No. 244 Wing RAF as a wing leader of their

Spitfires, under his old friend Wing Commander Brian Kingcombe. While Dundas

waited for the paperwork to be processed for his promotion and transfer, the

overall build-up to a spring offensive increased.

#

In late March and early April 1943 the weather improved. The

intensity of air attacks forced most German road traffic to move only at night.

The Boston bombers of No. 3 Wing SAAF, in their night-intruder role became the

most favoured strike aircraft to try to plug the night-time gap in interdiction

operations. The Bostons, nick-named the ‘Pippos’, short for ‘Pipistrello’, the

Italian word for a bat, exemplified how DAF had resisted becoming composed

solely of fighter squadrons. Once again DAF had demonstrated that its retention

of bombers made it unique in its make-up, and highly adaptable to ever-changing

circumstances.

During April the command of the Tactical Air Force (TAF)

raised the tempo of the air war, with the instigation of Operation STRANGLE.

The objectives were the interdiction of Rome, the battlefields at Anzio,

Cassino, and the enemy’s communication routes leading to the Gustav and Adolf

Hitler Lines. Just as it had at El Alamein and for the invasion of Sicily, the

massive air superiority of the Allies also created a No Fly Zone. This allowed

Eighth Army to move west with impunity over the Apennines to join Fifth Army

for the major offensives at Cassino.

The air interdiction strategy of Operation STRANGLE was the

idea of General John K., ‘Uncle Joe’, Cannon, commander of MATAF, to break the

stalemates at Cassino and Anzio. It aimed to do what its name suggests, to cut

off all rail, road and river routes across Italy, and prevent supplies reaching

the German armies. An unforeseen and beneficial outcome was the near paralysis

of any tactical mobility of the enemy forces.

DAF Kittyhawks, Mustangs, Baltimores and Spitbombers struck

at rail-tracks, overpasses, tunnels and bridges, in central and eastern areas

along the Teni-Perugia and Terni-Sulmona-Pescara lines. Trains were being hit

or halted as far as 120 miles from Rome. Of course, Operation STRANGLE was not

without its consequences. To counter the growing air-to-ground onslaught, which

clearly preceded another major offensive by Allied armies, the Germans took

their ground-to-air defences to another level. More intensive anti-aircraft fire

of various types imposed greater losses on Allied air forces, particularly the

fighter-bombers in their low level dive-bombing runs.

Although low level attack was the essence of fighter-bomber

operations, tactics varied in different ways, according to the type of

aircraft, and from squadron to squadron. In a typical Kittyhawk air-to-ground

attack for instance, the pilot would dive at around a sixty-degree incline, and

at up to about 400mph. Groups of four 88mm shells could be the first

anti-aircraft fire encountered. Set to explode at a specified height, bursts of

orange balls of fire, intermingled with puffs of black smoke, would usually

seek out the fighter-bombers before they were close enough to begin a descent.

The 88mm fire would then follow the Kittyhawk’s dive down to around 4,000 feet.

A near miss from an 88mm shell could seriously damage an

aircraft, while a direct hit would destroy it. Below 4,000 feet a mass of small

puffs of brown smoke from 40mm cannon shell explosions could be expected. This was

a rapid-fire barrage which would bring down many an aircraft. At 2,000 feet

20mm cannon fire would commence, very probably in heavy concentrations. A

direct hit at this altitude was perhaps the most lethal as, even if the

aircraft was still flying, the pilot had no time to try and regain height.

As the pilot dived closer to the ground, to release his

bombs within 1,500 feet of the target, he would be met with small-arms fire

from the enemy troops. As the pilot pulled out of the dive, the G-force

tightened and distorted his face into a grotesque mask. And in a desperate

climb away to safety, pilots were still being hunted by the anti-aircraft fire.

All they could depend upon to successfully complete the mission was their own

ability to fly the aircraft with skill, speed, and manoeuvrability – and of

course some luck.

Although from late March, because of the massive disruption

caused by Operation STRANGLE, no major through traffic was reaching the Italian

capital, air interdiction could not cut off all the enemy’s transport

lifelines. It could not entirely prevent the flow of some supplies, and the

movement of some reinforcements. What it did do was to severely weaken German

defences, and undermine their capability for sustaining indefinite resistance.

And at the same time Allied air superiority prevented the Luftwaffe from having

any material impact on Allied ground forces. This meant that some Allied

anti-aircraft units, with little or nothing to do, were converted to supplement

the army’s artillery. Allied air power also ensured that the German army stayed

on the defensive. As Air Chief Marshal (ACM) Slessor said, ‘if there had been

no air force on either side, the German Army could have made the invasion of

Italy impossible …’

From the beginning of April in the lead-up to Operation

DIADEM, No. 40 Squadron SAAF flew every day from first light to nightfall in

low-level reconnaissance. They photographed every German gun position and, as

spotters, they were in radio contact with the HQ of 6th Army Group Royal

Artillery (6 AGRA), for updating artillery target information. Using

large-scale maps and aerial photographs with numbered grids from prior

reconnaissance, pilots had direct communication with HQ 6 AGRA while they were

in the air, to pass on coordinates of enemy guns which they had spotted.

They also communicated with 239 Wing via the Rover David

Cab-rank, to send fighter-bombers against identified targets. Observation posts

on Monte Trocchio, staffed in a mix of RAF and Eighth Army Air Control officers,

directed Kittyhawks and Mustangs, such as on 15 May against communications

centres, and then on the next day to hit German mortar positions at Cassino.

In the days before the fourth battle to break through the

Gustav Line at Cassino and, a little farther north, its fallback, the Adolf

Hitler Line, the stalemate appeared to be entrenched. A new observer of the

Liri Valley from the distance of the surrounding mountains would have been

misled. The occasional gunfire, bomb-blast or shell-burst would have seemed

desultory, almost languid in the late Italian spring.

Flowers caressing the roadside half hid the coils of

telephone wire; the song of innumerable birds, which had grown used to the

fighting, only served to emphasise the fevered stillness of anticipation. The

peeling pink plaster of a roofless house, the twisted balcony rails, shimmered

like an artificial eighteenth century ruin in the liquid sun.

In reality the Allies’ tactical air forces were at work

around the clock, bombing raids hitting the German front lines and blocking all

rail lines to the north.

On 7 May DAF struck a most remarkable blow against the

Luftwaffe’s attempts to make some kind of threat against the coming offensive.

Squadron Leader ‘Duke’ Arthur was leading a Spitfire patrol of No. 72 Squadron

RAF over Lake Bracciano when they intercepted a formation of eighteen Bf109s of

I./JG 4. Arthur shot down one, and his fellow pilots claimed another eight

victories as they racked up a total of nine kills of the eighteen Bf109s.