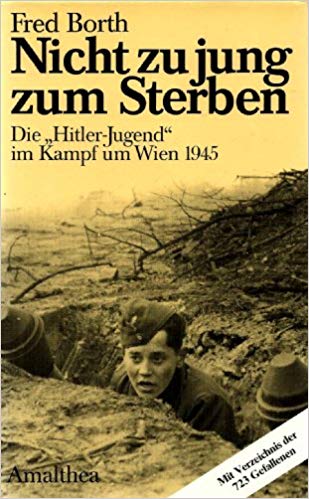

Nicht zu jung zum Sterben: Die “Hitler-Jugend” im Kampf um Wien 1945

Werewolf operations behind the Western Front were often

carried through with a distinct lack of enthusiasm. This was caused in part by

a lack of conviction among the general public, and even among some Werewolves,

that the encroaching Allied powers would treat the population badly,

notwithstanding Nazi claims to the contrary. On the Eastern Front, such

psychological factors moderating Werewolf activity did not exist. Underpinned

by years of racial stereotyping, the Nazi propaganda machine succeeded in

convincing most eastern Germans of the ‘barbarity’ of the Soviet armed forces,

and unhappily, these images were often reinforced by advancing Red Army

soldiers, who spent much of their time pillaging and raping. Had Goebbels

picked out of thin air the most garish and lurid descriptions of Soviet

misbehavior that he could imagine, he could not have come up with better copy

than the Soviets provided through the actual comportment of their forces. From

the warped perspective of the Werewolves, however, this disastrous situation

could not be played solely for advantage. Although the intense hatred of the

enemy necessary for guerrilla warfare existed, more than half of the population

of the eastern provinces was either so frightened or so browbeaten by Nazi

authorities that they picked up and fled in the face of the Soviet advance.

This mass exodus both deprived eastern Werewolves of a support base and

interfered with the logistics and communication channels needed to sustain

Werewolf operations. In addition, civilians left behind in the

Soviet-controlled hinterland were often so shocked by Soviet outrages that they

slipped into a state of numb impotence and were rendered incapable of thinking

about active or even passive resistance.

Despite these impediments, Werewolves went into battle

behind the Eastern Front at an early date and some units were at least

intermittently active. Unfortunately, surviving accounts of these operations

are scarce. The nature of Soviet anti-partisan tactics determined that not many

Werewolves survived their encounters with Red Army and Soviet secret police

troops; captives taken in skirmishes were apt to be shot in the nape of the

neck, the treatment that the Soviet leadership deemed suitable for irregular

forces. Until the final weeks of the conflict, even Volkssturm troopers were

often dispatched in such fashion. As a result, interrogation records are

scarce, a situation made worse by secretive Russian archival control of

whatever material of this sort that still survives, and because of the

typically savage treatment of Werewolf opponents, Russian veterans have usually

not been eager to include accounts of Werewolf incidents in their memoirs. Thus

what we know of the Werewolf in the East we know very much in part; we see

through a glass darkly.

IN THE BEGINNING

While the Rhineland HSSPf were just starting to organize

Werewolf recruitment in October 1944, harried SS-police officials in East

Prussia were already fielding their first Werewolf detachments, and Prützmann

could report that these units were already operating ‘with some success.’ This

progress was achieved despite crippling organizational problems and personnel

difficulties. When Hans Prützmann had been sent to the Ukraine in 1941, he was

not completely relieved of his existing job as HSSPf in the East Prussian

capital of Königsberg. Rather, he was replaced by an Acting-HSSPf,

Gruppenführer Georg Ebrecht. As a result, when Prützmann was chased out of the

last German footholds in the Ukraine in the summer of 1944, it was unclear

whether he would reclaim his old position in Königsberg. The post was still

officially his, but the fact that he was an archenemy of the local Gauleiter,

Erich Koch, did not suggest much chance of a happy homecoming. This ambiguity

was resolved by the illness of Ebrecht, who became incapacitated in early

September 1944, a situation that seemed to demand that Prützmann walk back

through the door and replace his surrogate, at least temporarily. By 11

September 1944, Prützmann was back in Königsberg, functioning in this capacity.

Ebrecht’s illness, originally expected to last six weeks, eventually forced his

retirement, so that by October 1944 Prützmann found himself potentially saddled

with his old job. Since he was concurrently appointed as national Werewolf

chief and as plenipotentiary to Croatia, he lacked sufficient time for his

regional duties in East Prussia, and in early December, Otto Hellwig, a

hard-drinking former member of the Rossbach Freikorps in the Baltic, was

appointed as the new Acting-HSSPf-North-East. Hellwig had worked closely with

Prützmann in the Ukraine, although in 1943 he had been sent back to East

Prussia to become SS-police commander in the newly-annexed frontier region of

Bialystok. At the time, rumours abounded that Hellwig’s alcoholism had prompted

the recall.

When Prützmann was in Königberg in September 1944, he began

work on mobilizing small Werewolf groups, which were tasked with allowing

allowing themselves to be overrun by any imminent Soviet advances into the

province. As his Werewolf Beauftragter, Prützmann chose Obersturmbannführer

Schmitz, a senior official with the Security Police in Königsberg. A darkhaired

native of the Eifel district who constantly struggled to stay one shave ahead

of his heavy beard, Schmitz had been stationed with Prützmann’s staff in Kiev

and had been cultivated by the SS general as a protegé. Schmitz ran the East

Prussian Werewolves until February 1945, when he was released because of

illness. One Werewolf recruited during this period later remembered that the

headquarters staff referred to itself as ‘First Military District Command,

Abwehr Office – Königsberg.’

The pace of developments was soon forced by the Russians. In

mid-October 1944, with Soviet armies already bearing down on the northern towns

of Memel and Tilsit, Third Byelorussian Front suddenly sliced into the boundary

regions east of Insterburg, briefly capturing Goldap and throwing the entire

province into an uncontrolled panic before German forces staged a successful

counter-attack, partially destroying the Red Army’s 11th Guards Rifle Corps at

Gumbinnen. Goldap was retaken by the Wehrmacht on 5 November, although the Red

Army retained control of several hundred square miles of German territory along

the East Prussian frontier.

These events resulted in the enemy capture of the

operational zones plotted for several of Schmitz’s Werewolf units. One of

these, a nine-man ‘Special Kommando’, had been formed in early October and was

recruited from the ranks of the Luftwaffe’s ‘Hermann Göring’ Division, a

detachment of which was in the area in order to guard Göring’s country estate

on the Rominten Heath. Major Frevert, the commandant of the Göring residence,

was charged by the Königsberg ‘Abwehr Office’ with choosing and training a

Werewolf team, and with preparing three hidden caches in the woods, each

supplied with three months’ worth of ammunition and food stocks. The unit was

also equipped with two radio transmitters and ten carrier pigeons. Feldwebel

Bioksdorf was placed in direct command and was responsible for leading the Werewolves

in battle.

Although the Soviet offensive threw Werewolf plans into

flux, cutting short the time needed for training and preparations, Bioksdorf’s

unit was deployed in the large area overrun by the Soviets in mid-October, and

remained active in the smaller strip of territory retained by the Russians

after their retreat. By November, the unit was one of six similar formations in

operation behind the lines of Third Byelorussian Front. Its mission was to

report on the nature of Soviet transport passing through the Rominten area and

to harass this traffic whenever and wherever possible. Bioksdorf also had a

mandate to organize small groups of bypassed German soldiers and thereby create

new guerrilla bands. Finally, the unit was also supposed to report on relations

between Soviet forces and German civilians who had failed to evacuate the

frontier region. Investigations of this sort produced a shock: along with

counter-attacking German troops, Werewolves were among the first Germans to see

the initial evidence of atrocities in areas overrun by Soviet troops: women

raped and then crucified on barn doors; babies with their heads smashed in by

shovels or rifle butts; civilian refugees squashed flat by Russian tanks that

had overtaken their treks. In areas recovered by the Wehrmacht, the Germans

were quick to call in observers from the neutral press in order to witness what

had been done. Third Byelorussian Front also evacuated almost all remaining

German males and most females from areas in the rear of the front, a tactic

which, according to Hellwig, was extremely effective in isolating partisans.

Werewolves, he reported, ‘only [had] a very short time in which to commence

their work.’ Anyone who looked to the Soviets even vaguely like a partisan was

killed immediately. This paranoia was probably a factor in the deaths of fifty

French POWs, dressed in semi-military garb, whose bodies were discovered in the

Nemmersdorf area.

During the brief period in which the Bioksdorf Werewolves

were free agents, they managed to send ten radio massages back to Königsberg

and they also attempted to blow up two bridges, although in typical Werewolf

fashion they lacked sufficient charges to finish the job in either case. On 14

November 1944, Soviet Interior Ministry troops spotted three guerrillas on the

Rominten Heath, and although two of these men were killed, the third was taken

alive and thereafter provided the Soviets with full details about the Werewolf

‘Special Kommando.’ At the same time, the Soviets also seized over fifty pounds

of Werewolf explosives and twenty-five hand grenades. Shortly afterwards,

soldiers of 11th Guards Rifle Corps overran the remaining members of the unit,

including Bioksdorf himself.

ANOTHER MISSION BEHIND RUSSIAN LINES

In addition to East Prussia, Austria served as another

Werewolf stronghold. After German reverses along the front in Hungary, most

notably the Soviet encirclement of Budapest, Prützmann decided to prod the

Austrians into taking some precautionary measures. In early January 1945, he arrived

in Vienna and met with the local HSSPf, Walter Schimana, and the Gauleiter of

Lower Austria, Hugo Jury. Neither of these Austrians possessed the iron will

for which the Nazis were supposed to be famous. Schimana was a narrow-minded

little man already on the way towards a collapse that would eventually see him

sent home to rest and recuperation with his family in the Salzkammergut; Jury

was a tougher nut but was strongly opposed to the recruiting of Hitler Youth

boys for guerrilla warfare, a distinct impediment to the kind of local

organization envisioned by Prützmann. Both men, however, gave Prützmann their

grudging compliance, and they agreed to appoint a local party official and

Volkssturm commander named Fahrion as Werewolf Beauftragter. Shortly after

Prützmann returned home, Karl Siebel also showed up in Vienna and met with the

local Brownshirt commander, Wilhelm von Schmorlemer, in an effort to get him to

cooperate in the project.

In mid-January Fahrion attended a four-day Werewolf course

in Berlin and returned home eager to get to work on Werewolf matters. Early in

the following month, he convened a meeting of local Kreisleiter at Heimburg and

requested their help in making manpower available.4 It was through the party’s

subsequent recruitment campaign that a dedicated Hitler Youth activist, the son

of a local party official, was swept into the movement. This young man, who was

interviewed after the war by the British historian and museum curator James

Lucas, had an extremely interesting story to tell. Feeling that Werewolf

training would be more exciting than the alternative – serving as a Flak gunner

– he volunteered in February 1945 for a special training course at Waidhofen,

on the Ybbs River. Entrants into the five-week program were immediately stripped

of their personal possessions and were refused any chance to maintain contact

with their families; they were told that they now belonged only to the Führer.

They were trained in the use of German and Soviet weapons, demolitions,

survival techniques and basic radio precedure. Rigorous field exercises

included prolonged night-time marches which culminated in the participants

having to dig narrow foxholes, which were supposed to be so well camouflaged as

to be undetectable in daylight. Trainees who performed below standard were

beaten by their SS instructors.

Meanwhile, in the outside world, the failure of Wehrmacht

counter-offensives in Hungary had been met in March 1945 by seemingly

unstoppable drives by Second and Third Ukrainian Fronts, a turn of events which

by early April had carried the Red Army into eastern Austria. Fahrion had been

ordered in March 1945 to report his preparations to Wehrmacht army group

intelligence officers as soon as German combat forces were pushed back into

Austria, and when rear echelons of Army Group ‘South’ appeared, he sent a

representative to make contact with them. The main plan, at this stage, was to

field about twenty small detachments of ten persons each, although it is not

clear that all of these were ready before the Soviets arrived. Fahrion’s people

were also short of radio equipment because Prützmann had failed to deliver a

number of devices that he had promised, all of which made it difficult for

field detachments to stay in contact with a regional Werewolf signals centre at

Passau. Nonetheless, some available manpower was sent to the Leitha Mountains,

south-east of Vienna. Schimana later remembered that Fahrion repeatedly bragged

about the exploits of a ten-member group based at Oberfuhlendorf, near the

Hungarian enclave of Sopron.

When these operations were launched, Lucas’s informant was

sent northward as part of a four-man group to monitor Soviet troop movements in

the Protectorate of Bohemia-Moravia (now the Czech Republic). This was a

precarious assignment because it was assumed, quite rightly, that if the

guerrillas were detected by Czech civilians, they would be readily betrayed to

the Soviets. As a result, the group had to stay concealed in the woods,

constructing small and inconspicuous cooking fires as prescribed in the

Werewolf handbook. Although they were supposed to ‘smell of earth’, their lack

of bathing facilities soon left them smelling more like sweat, a danger since

body odour could serve as a give-away for Soviet pursuers and tracking dogs. Supplies,

however, were plentiful: when Lucas’s source was selected to accompany the

group leader to a supply cache, he was surprised to see a small mountain of

weapons, food, clothing and bedding – enough to keep the unit going for years.

And it was so well hidden that the spot where it was stored was literally

invisible from a yard away.

Reconnaissance outposts were manned by one Werewolf who

maintained a tally of passing Soviet tanks, trucks and guns, while a second

guerrilla kept a watch over his partner. The great masses of Soviet men and

material, moving day and night, inspired nothing short of awe, particularly in

view of the fact there was no local trace of any German troops or aircraft.

Such was the Soviet sense of security that vehicles travelled at night with

headlights blazing. In one case, however, this sense of complacency was rudely

disturbed. When a small patrol of motorized infantry came too close to the

Werewolves’ hideout in the woods, the guerrillas decided to use force in

eliminating the threat. Mining a deep gorge through which the Soviet vehicles

were expected to pass, the partisans took up lateral firing positions – once

again a textbook maneouvre described in the Werewolf manual. When the small

Russian convoy passed through the defile, the lead vehicle hit a mine and as

the driver of the last truck shifted into reverse, he hit a mine as well. The

Werewolves then shot up the trapped vehicles and the soldiers inside them.

After swinging further north one night in mid-April, the

guerrillas then hooked southward, back into Austria, moving closer to the

Werewolf concentration point in the Leitha Mountains. It was while observing

northward-bound armour near Bruck-an-der-Leitha that the unit’s good fortune

finally ran out. Three of the guerrillas were dug in foxholes on the slope of a

hill overlooking the road; the fourth, Lucas’s witness, was in another hole

over a thousand feet further up the slope, sending radio messages back to his

Werewolf controllers. Suddenly, for reasons still unclear, some of the tanks

swerved off the road and began clambering up the slope toward the Werewolf

foxholes. At this terrifying sight, one of the guerrillas panicked, jumped out

of his hole and began running headlong away from the tanks. He was promptly

shot down and the Soviets then began methodically searching the hill for other

foxholes. When the other two entrenchments in the forward line were discovered,

T34 tanks ran over them and spun their treads, crushing the occupants and

burying them in their own graves. Then, as the horror-struck radio operator

crouched in his hidey-hole, the tanks rolled further up the hill, looking for

more trenches and firing their machine guns furiously. The armoured crews got

out and searched around on foot, until they finally tired of beating the bushes

and drove away. Lucky to be alive, the sole survivor of this engagement stayed

covered in his foxhole until dark, whereafter he crawled out and slunk away

without checking on the condition of his comrades’ bodies.

Having dodged the proverbial bullet, Lucas’s informant then

headed south, mainly with the intention of contacting other Werewolves

operating along the Austrian-Hungarian frontier. He saw another Werewolf

loitering outside a train station, and then launched into one of the cloak-and-dagger

recognition rituals so beloved by secret organizations, rolling a coin over his

fingers and exchanging other elaborate signs and countersigns before contact

could safely be made. Once he had established his bona fides, he began

operations with a new Werewolf group, the main mission of which was mining

Soviet transportation routes and painting threatening mottoes in order to

intimidate local civilians. ‘Slogans reminded them,’ he later recalled, ‘that

the Werwolf was watching and that Hitler’s orders were still to be obeyed, even

under foreign domination.’ Needless to say, such activity made the Werewolves

unpopular among rural villagers, most of whom wanted the war to end and cared

little about which occupying power was garrisoning the cities.

After several weeks of minelaying and sloganeering, the

Werewolf group leader decided that the unit had become stranded too deeply in

the Soviet-occupied hinterland, and that it was necessary to shift their zone

of operations westwards. While on the move through a village east of Linz, the

Werewolves were accosted by a party of drunken Russians who shouted that Hitler

was dead and the war was over. To learn this ‘devastating’ news through such

means was considered the ultimate humiliation, particularly since the

guerrillas were encouraged to toast their leader’s death and their country’s

defeat. With the final capitulation soon confirmed, the Werewolf unit

disintegrated. Lucas’s narrator went to Linz and subsequently made his living

trading supplies from secret Werewolf caches on the black market. ‘It was’, he

claimed, ‘a miserable and ignoble end to what had begun as a glorious national

adventure.’

THE VIENNA FOREST DIVERSION

While the HSSPf-Vienna was directly training and deploying

Werewolf troops, Hans Lauterbacher, the Hitler Youth district leader in the

Austrian capital, was launching efforts on a much larger scale. Two local

battalions of Hitler Youth fighters were codenamed ‘Werwolf’, and although they

were attached to an SS ‘Hitler Youth’ Division and were intended to serve

mainly in conventional combat, some of their cadres were trained in guerrilla

warfare and were available for deployment in ‘Jagdkommandos’, that is, raiding

detachments formed for operations behind Soviet lines. Hugo Jury and the Vienna

Gauleiter, Baldur von Schirach, were both opposed to such preparations, but

Siegfried Ueberreither and Friedrich Rainer, the Gauleiter of the south-eastern

provinces of Styria and Carinthia, were both strongly supportive, and much of

the prospective guerrilla war was expected to be fought in their Gaue.

One of the recruits for Hitler Youth Werewolf training was

sixteen-year-old Fred Borth, an enthusiastic young man from Vienna who had made

rapid progress through the ranks of the Hitler Youth despite being raised by a

great uncle who was a staunch Austrian republican. Although Borth had dreamed

of becoming a pilot, local Hitler Youth chief Walter Melich got the Luftwaffe

to release him for ‘particularly important military tasks’, and in January 1945

he sent him for training in anti-tank warfare at a camp near Hütteldorf. Once

the decision was made – given the continuing Soviet threat in Hungary – to

prepare all Austrian Hitler Youth boys for battlefield service, Borth, as a

Hitler Youth leader, began training as an officer candidate. Melich then

instructed him to attend a special Werewolf camp at a hunting lodge near

Passau, a facility established under the aegis of HSSPf Schimana. Melich

vaguely described the mandate of the camp as teaching ‘the art of survival’;

Borth did not stop to think about why it was called a ‘Werwolf’ facility.

The young recruit got quite a surprise at Passau. The camp

commandant was a psychopathic SS Sturmbannführer popularly known as ‘the

Bishop’ because he was an ordained Eastern Orthodox priest. A veteran of the

Austrian imperial military intelligence service, ‘the Bishop’ had later served

as an advisor to the fascist dictator of Croatia and had been sent from there –

through the intervention of Prützmann – to run the school at Passau. ‘The

Bishop’s’ idea of training was to get his charges to lie on railway ties and

let trains pass over them, or to show his students how to commit suicide by

folding back their own tongues over their throats. The pièce de résistance of

the training schedule was a wild run through an obstacle course that started

with ‘the Bishop’ tightening a noose around the necks of the participants, so

that were choked nearly to a point of unconsciousness and had to navigate the

course in this condition. To add to the sport, live machine-gun ammunition was

fired at the trainees, and grenades were tossed behind them in order to keep

them moving.

‘The Bishop’s’ political instruction had similarly extremist

tendencies. He handed out photographs of the October 1944 Soviet atrocities in

East Prussia, and he showed films about Anglo-American bombing raids on German

cities. He also had lots to say about rapes and unprovoked shootings, some of

which were currently being reported from areas across the border in Hungary. Joseph

Stalin and Franklin Roosevelt’s son, Elliot, were alleged to have talked about

the need to shoot 50,000 Germans; American Treasury Secretary Henry Morgenthau

reportedly wanted to turn Germany into a ‘de-industrialized’ medieval cowpatch,

to sterilize its adult population and to ship Germans to Africa and other parts

of the world in order to perform forced labour. ‘The Bishop’ admitted that the

Germans themselves had made mistakes in Eastern Europe, and that the growth of

anti-German resistance had been solely related to this factor. However, ‘we

can’t wrack our brains about what should have been done differently.’ ‘We

must,’ he argued, ‘come to terms with the facts.’ It was true that Germany

would probably be overrun and that the Werewolves would eventually have to

operate on an entirely ‘illegal’ basis, but ‘we presently see,’ he claimed,

‘the same prerequisites that have set the stage for partisan warfare

[elsewhere]

.’

Having finished his guerrilla training on 7 February, Borth

was returned to Hütteldorf and to his Hitler Youth company, which he

accompanied into battle when the Soviets smashed into Austria in early April

1945. Borth performed well during the heavy fighting in Vienna, being awarded

first and second class Iron Crosses, but he was not brought along when the

Hitler Youth companies were eventually withdrawn to Bisemberg along with the

rest of 6th Panzer Army. Instead, on 10 April he was ordered to report to a

provisional SS Security Service headquarters in the besieged Austrian capital.

There he was surprised to find some senior SS officers waiting to greet him,

including ‘the Bishop’ and HSSPf Schimana. These officers told Borth that he

had been selected to command a 65-man Jagdkommando’ drawn from a Hitler Youth

‘special duties’ batallion, a unit that would henceforth function under the

joint control of the SS Security Service and the Prützmann organization.

Several Security Service men and a Ukrainian specialist in guerrilla warfare

would be attached to the company as advisors; ‘the Bishop’ would be Borth’s

contact man at headquarters. The job of the unit was to create unrest in the

enemy hinterland and thereby provide indirect help to beleaguered Wehrmacht

forces at the front, since the Soviets would presumably have to redirect

resources in order to sweep clean their own lines of communication. ‘You’ll be

the game rather than the hunter’, he was told. He was instructed to operate at

night, not only to protect his forces, but to make the unit’s numbers seem more

significant than they really were. Contacts with the population were to be kept

to a minimum, and he was expressly warned to beware of ‘spies and traitors.’ He

was shown a general staff map of secret supply caches in enemy territory, but

he was advised that the preparation of many dumps had not been completed in

time, and that supplies were limited. Therefore, he ought to make moderate

demands upon the caches, since he might need to come back to them later.

Several additional problems were also discussed. Although

Borth’s formation was given a wireless set, there was no replacement for the

highly trained radio operator who had been part of Borth’s former unit, and he

only received one medical attendant, not much help for over sixty boys, none of

whom had ever taken a first aid course. Borth confessed that he had no idea

what to do with anyone badly wounded during the enterprise. His superiors

expressed sympathy with Borth’s concerns, but they noted that they were not

allowed to draw specialist personnel from the front, and that radio monitoring

– not operating – was the only thing that SS security and police personnel were

properly trained to do. In addition, there was only a small cadre of trained

radio operators who had to be divided amongst various guerrilla units using the

Austrian radio network. As for medical problems, it was pointed out that

Wehrmacht field hospitals and dressing stations were no longer being evacuated

– medical staff were now being left for Soviet captors along with the badly

wounded – and this practice was causing shortages of highly trained personnel

that could no longer be made good. Given this situation, it was almost a

miracle that this ‘unloved Prützmann unit’ had been allotted any medical help

at all from the Waffen-SS. Sending a full-fledged doctor with the ‘Jagdkommando’

was out of the question. In any case, physicians could hardly perform difficult

surgery in a wood or a bunker. There was always the possibility of recruiting

local country doctors to assemble ad hoc operating rooms, but the SS trusted

neither the doctors nor their neighbours not to betray Nazi partisans to the

enemy. As a result, Borth was told to depend on his own resources, however

inadequate these might seem. In the final analysis, heavily wounded Werewolves

could be given cyanide capsules rather than being allowed to suffer and die in

pain.

Later in the day, Borth was directed to the Augarten section

of Vienna and introduced to his new troops. Most of them were fifteen- or

sixteen-year-old boys from Vienna who had already been deployed in Augarten,

carrying shells for the artillery of the SS ‘Das Reich’ Division. Borth’s main

advisor was a rugged Ukrainian bruiser named Petya Orlov, a man whom Borth

liked but never entirely trusted, seeds of doubt having already been planted by

‘the Bishop.’ On the night of 10 April, Borth took his group to an abandoned

factory near the switching yards of the North-West Railway Station, whereafter

they advanced to some ruins and hunkered down to sleep. ‘The Bishop’ showed up

around noon, bringing with him a police officer from the Vienna Canal Brigade

who was assigned to serve as a guide to the labyrinth of subterranean Vienna.

During a lull in the fighting, the company crossed the Danube Canal over a

bridge partially obscured by smoke, and they then descended into a network of

sewage tunnels and run-off drains, hoping to infiltrate Soviet lines by walking

under the feet of Red Army troops on the surface. It was a hellish, pitch black

environment, swarming with rats and contaminated with nearly unbearable odours

from excrement and the bodies of dead animals dumped into the tunnels after

bombing raids. A few human bodies were also floating in the slime. During the

passage through this stygian maze, one of Borth’s Security Service escorts

slipped in the muck and injured his knee so badly that he could no longer walk

without aid. There was talk of bringing him to a civilian hospital on the

surface, but the SS man knew that the Soviets were sweeping hospitals in search

of wounded SS troopers, so he drew his pistol and shot himself through the

head. A Hitler Youth guerrilla was bitten so badly by rats that he too required

medical attention. He was led to a hospital after the Werewolves emerged from

the tunnels, but the lad never escaped the impact of his subterranean tribulations;

his right arm was amputated below the elbow and he later took his own life.