The U-Boats of World War One

Germany was one of the last of the major powers to begin a

submarine-building programme for her navy. In many respects she followed the

British model, developing and experimenting with new submarine designs rather

than putting them into full production and then discovering that there were

operational or constructional problems. While the British intended to use the

submarine to defend bases and the coastline, the German navy’s intention was to

use them as an offensive arm.

The key battle area would be the North Sea. This meant that

any submarine deployed by the Germans would have to have a good operational

range, the ability to remain at sea in the challenging winter months and a good

surface speed, along with a high level of reliability.

It was not until February 1905 that the German navy awarded

the first contract to build a submarine to the Germania Yard at Kiel. U-1 would

be a 238-ton vessel with a kerosene engine and a single 45 cm bow torpedo-tube.

One of the problems was that the kerosene created clouds of white smoke that

could be seen for miles. Nevertheless, U-1 was finished in December 1906, and

in the meantime a second and larger submarine had been commissioned to be built

at the Imperial Dockyard at Danzig – U-2. In August 1907 two more slightly

larger submarines, U-3 and U-4, were also ordered. It transpired that U-1 was

unable to meet the operational requirements of the German navy, and the engine

was not reliable enough.

The German navy was looking for a vessel that had a

2,000-nautical-mile surface endurance, a speed of 10.5 knots underwater, a

surface speed of 15 knots, four torpedo tubes, two bow tubes and the ability to

supply a crew of twenty with seventy-two hours’ air supply. Although the next

twelve submarines were built with these specifications in mind, they did not

fulfil them.

By 1912 it was still considered to be practicable only for

the submarines to be out operationally for five days, working no more than 300

nautical miles from their base. In effect this meant they could operate on the

eastern side of England and just into the English Channel from Heligoland.

The German’s first submarine casualty took place on 9 August

1914, when U-15 was rammed and sunk by HMS Birmingham. U-13 had been due to

return from patrol on 12 August, but she failed to appear, in all probability

having struck a German mine.

The German submarines had more success the following month

when on the morning of 22 September U-9 sank three British cruisers, HMS

Aboukir, HMS Cressy and HMS Hogue. She also managed to sink the cruiser HMS

Hawk on 15 October.

Technically, the U-19 Class of German submarine was an

enormous step forward. It had a diesel engine, 50 cm torpedo tubes; it was much

larger and longer and it also had six torpedo tubes. This type of vessel would

provide the blueprint for many of the German submarines up to U-116.

Later on in the war larger submarines were ordered by the

German navy, but many of these vessels were never completed. Those that were

completed were often named after early German submarine heroes. U-140, for

example, was named after Kapitän-leutnant Weddigen, who had commanded U-9 in

1914 but had been killed in action in U-29.

The Germans also deployed mercantile submarines, notably

Deutschland (U-155). She was a blockade runner carrying cargo to and from the

United States. She made two trips in 1916. Bremen accompanied her on the second

trip but never arrived. A third, Oldenburg, was converted into a cruiser U-boat

before she was completed. Ultimately Deutschland was also converted, with a

pair of bow torpedo tubes and a pair of 15 cm guns.

Later in the war an improved version of this submarine

cruiser was proposed, with six torpedo tubes and heavier guns. UD-1 was started

but never completed.

When the Germans overran parts of Belgium in 1914 they

acquired Bruges and Zeebrugge, both of which would be ideal submarine bases

and, of course, closer to the proposed areas of operation. The Germans decided

to introduce smaller coastal submarines. These were ordered in November 1914

and came into service at the beginning of 1915. They were known as Type UB

submarines, just 88 ft 7 in. long, with a displacement of 127 tons and a pair

of torpedo tubes. The idea was that they would be built in sections,

transported by rail and then assembled at their base. The first was UB-1, which

would operate in the Adriatic. The Type UB-3 came into service during the

1917–18 period. It was much larger: 182 ft long, a displacement of 520 tons and

five torpedo tubes. These were such a success that they were to prove to be the

blueprint upon which the Germans would design their Type VII U-boats for World

War Two.

The Type UB submarines were designed for coastal operations.

A smaller, Type UC, of which there were two variants, was also designed as

minelayers. These too were transported by rail for final assembly, but the

early ones had no means of offence or defence, although later models had

torpedo tubes.

The British captured UC-5 and made a careful examination of

the wreck of UC-2. This helped them enormously in unravelling German mining

strategy and allowed the British to modify their own E Class submarines as

minelayers.

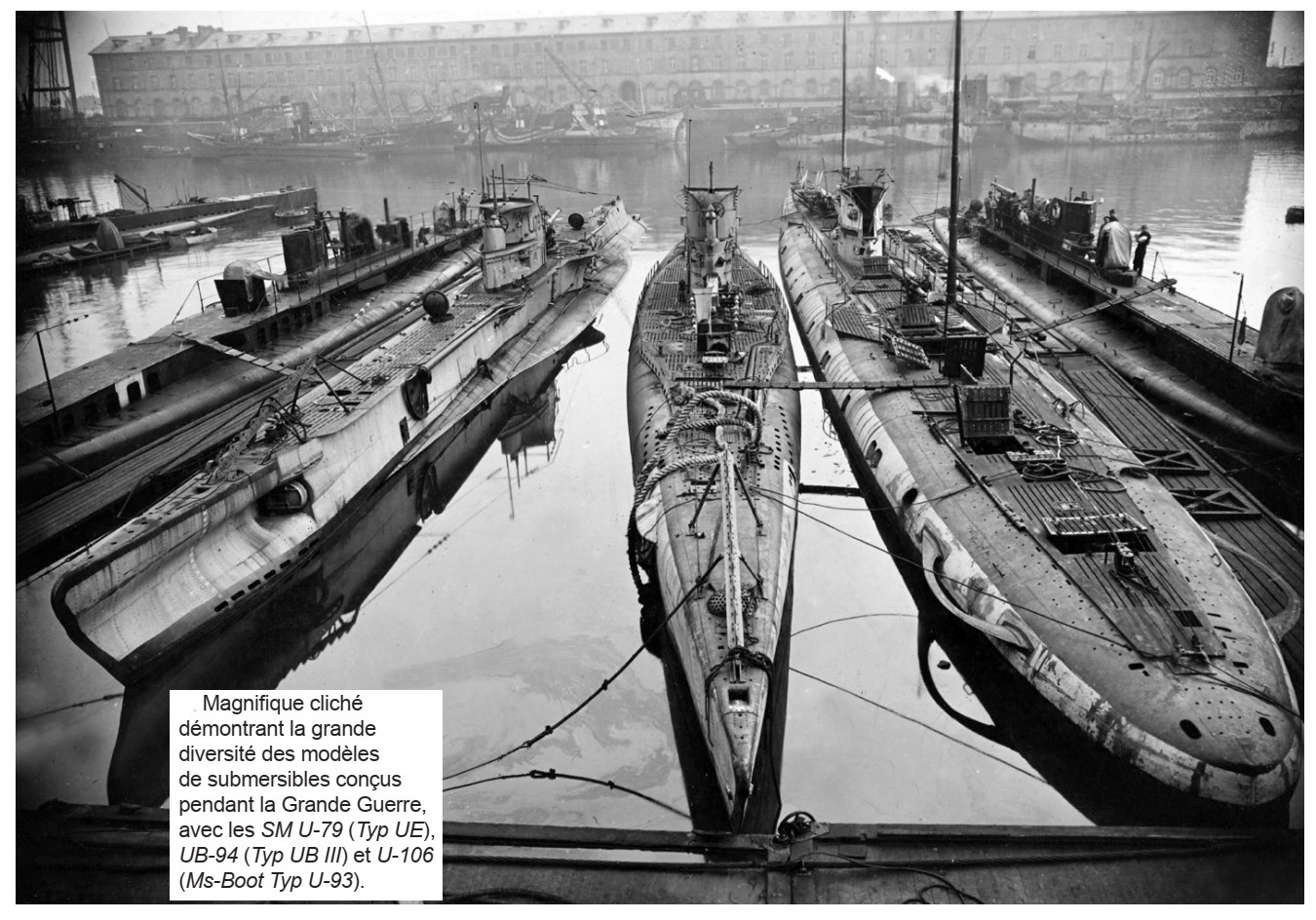

There were also smaller Type UE ocean-going minelayers that

had torpedo tubes. The later submarines in this series could operate off the

United States coastline. A further Type UF coastal submarine was also planned.

This was similar to UB-2 but would have four or five 50 cm torpedo tubes, but

the Germans did not manage to complete any of these before the end of the war.

At the beginning of World War One the Germans had around

twenty operational U-boats working with the High Seas Fleet. Initially they

were deployed as a defensive screen; however, within days an ambitious plan was

hatched to launch an attack on the British Grand Fleet at Scapa Flow. This was

the operation in which U-15 was lost. U-5 and U-9 turned back because of engine

problems, and U-18, although it managed to penetrate Scapa Flow, was sighted

and sunk on 23 November 1914. Overall the German U-boats had lost 20% of their

strength without claiming a single kill.

September 1914 had been a more promising month: U-21,

commanded by Otto Hersing, had sunk the British light cruiser, HMS Pathfinder.

He was to become a U-boat ace, launching twenty-one war patrols over a

three-year period in which he sank thirty-six ships, including two battleships.

As we have already seen, U-19 had claimed the three British destroyers off the

Hook of Holland in September.

On 20 October 1914 an event took place that was to set the

scene or terms of engagement for both world wars. Off southern Norway U-17

engaged the British steamer, SS Glitra. Kapitän-leutnant Feldkirchner boarded

the vessel to inspect the cargo, after which he allowed the crew to board

lifeboats, and then he sank the steamer.

On 26 October the pattern continued when Kapitän-leutnant

Schneider on U-24 torpedoed SS Admiral Ganteaume without warning in the Dover

Strait. This was the first time that a merchant vessel had ever been attacked

in this way. Henceforth merchant vessels would become the prime target in

attempts to wreck the economy of a wartime foe.

The significance of these two events was not lost on either

the British or the Germans. The British had already mounted a blockade of

Germany at a distance. Now the Germans felt confident enough to be able to

launch their own counter blockade. Had they been able to maintain this blockade

throughout the war perhaps the Allied victory would have been compromised.

By the end of 1914 the Germans had lost five U-boats, but

had sunk ten merchant vessels and eight warships. On 18 February 1915,

unrestricted U-boat warfare was introduced by the Germans. Henceforth any

vessel found around the British Isles would be sunk without warning. Deciding

whether a vessel was truly neutral was at the discretion of the U-boat captain.

The Germans lost Weddigen in March 1915 when U-29 was rammed

by the British battleship HMS Dreadnought. His vessel was lost with all hands.

One of the most notorious submarine incidents took place on

7 May 1915. Kapitän-leutnant Schwieger, commanding U-29, fired a torpedo at RMS

Lusitania to the south of Ireland. She sank in eighteen minutes and 1,200

people lost their lives, including 128 Americans. Controversy still rages

around the loss of the vessel. She was registered as part of the British Fleet

Reserve, she was in a war zone and arguably she was carrying munitions.

However, such was the storm of protest from neutral America at the loss of her

civilians that the German submarines were now ordered to ignore passenger

liners.

On 19 August 1915, there was a similar but less well-known

incident. Kapitän-leutnant Schneider (U-24), believing RMS Arabic to be a troop

transport, sank her. But among the forty-four dead were three Americans. The

Germans feared a backlash from the Americans, and as a consequence, on 20

September 1915, the U-boats were withdrawn from British waters, and for a while

the primary area of operations became the Mediterranean.

By the end of 1915 the Germans had lost twenty U-boats, but

had claimed 855,000 tons of shipping. The UC minelayers had claimed another

ninety-four vessels. However, on 24 March 1916, UB-29, commanded by

Oberleutnant Pustkuchen, sank the French cross-channel ferry, The Sussex, which

had been mistaken for a minelayer. Eighty people were killed, among them

twenty-five Americans.

There was another enormous diplomatic row, and this time the

Germans withdrew all of their vessels on 24 April.

For the Allies the losses were beginning to be serious, and

new counter-measures were needed. Up to this point, with depth charges still

under development, a submarine could only be destroyed by ramming it or hitting

it while it was on the surface. The British now created the Q-ship.

As far as the U-boat was concerned, the Q-ship would look

like a tramp steamer, but in reality it was armed with guns and torpedoes, and

its cargo was wood or cork, in order to make it almost unsinkable. The Germans

discovered to their cost that these Q-ships were incredibly dangerous. U-36 was

sunk by HMS Prince Charles on 24 July 1915. Less than a month later U-29 was

sunk by HMS Baralong. One of the hardest-fought engagements between a Q-ship

and a U-boat took place on 8 August 1917, when an eight-hour battle took place

between UC-71 and HMS Dunraven. In all, Q-ships managed to destroy fourteen

U-boats and damage sixty others. Twenty-seven Q ships were lost.

In October 1916 U-boats returned to British waters, and in

that month alone they sank 337,000 tons, and between November 1916 and January

1917 another 961,000 tons. In February 1917 a further 520,000 tons were sunk.

U-boat successes steadily continued, reaching a peak in April 1917, when

860,000 tons were sunk.

With the USA finally declaring war on Germany in April 1917,

the numbers of potential merchant victims soared. In the period May 1917 to

November 1919, 1,134 convoys, consisting of 16,693 merchant vessels, made their

way back and forth across the Atlantic. This new convoy system would lead

directly to the defeat of Germany: she simply could not stop the flood of

munitions, supplies and men. The tide had certainly begun to turn against the

German U-boat threat.

According to the Armistice the 176 operational German

submarines were handed over between November 1918 and April 1919. The German

navy had started the war with twenty-eight U-boats; 344 had been commissioned

and 226 were under construction when the war ended. The Germans had sunk over

twelve million tons of shipping, or 5,000 ships. Seven submarine commanders,

headed by Lothar von Arnauld de la Perière (450,000 tons) topped the list. The

U-boats had been seen to be a powerful, though not a decisive, weapon of war.

The 176 operational U-boats handed over to the British were evaluated,

stripped, parcelled out to Allies or scrapped. Germany was then prohibited from

building or possessing U-boats.

Q-ship trap

A promising tactic was to hit the U-boat at the time it was

doing its deadly work – attacking merchant ships – and this was done in two

ways. More and more merchant ships were being equipped with deck guns to defend

themselves. With a properly trained gun crew, a merchant ship had a good chance

of striking a crippling blow against a U-boat, itself only armed with a single

gun, and with a highly vulnerable pressure hull. A more offensive tactic was

the use of Q-ships, small merchant vessels with concealed guns on the upper

deck. The theory behind these ships was that they would clearly be too small to

be worth a U-boat captain using a precious torpedo to sink one. However, if he

closed in on the surface to a range that would allow him to finish off an

apparently defenceless target with his deck gun, the Q-ship’s main armament

would be revealed and a powerful barrage would quickly finish off the attacker.

For the idea to work, the Q-ship’s camouflage had to be

perfect, even when watched through powerful binoculars by a cautious submarine

commander. For example, one converted fishing vessel was towing nets in the

correct way, but another fishing boat spotted that there were none of the usual

swarms of seagulls competing for scraps from the catch. In the case of larger

vessels, which might attract a torpedo, cargo holds would be filled with empty

barrels or baulks of timber for greater buoyancy. Guns were disguised as sheep

pens – providing fresh meat for the crew on a long voyage – or as life-belt

holders. If a submarine stopped the Q-ship, the cover of a helpless merchantman

might have to be maintained up to the crew taking to the lifeboats, leaving

enough trained men hidden onboard to man the guns and open fire when the U-boat

least expected it.

HMS Arbutus was an Anchusa-class sloop, completed as a

Q-ship and based at Milford Haven. She had only just entered service, having

been launched on 8 September. On 15 December she was on patrol some twenty-five

miles off the Welsh coast in the St George’s Channel under her captain,

Commander Charles Herbert Oxlade RNR. Oxlade, born in 1876, was something of an

adventurer having gained an aviator’s licence in 1913 and served as a volunteer

trooper in the Boer War. Now he was offering his ship as a target for U-boats.

The weather was filthy, blowing a gale and with rough seas,

when Arbutus was hit by a torpedo from UB-65. Oxlade ordered abandonment, for

real rather than deception as the ship was badly hit but stayed on board

himself, along with his first lieutenant and a stoker party, to try to save his

ship. Rescue vessels from Milford Haven attempted to tow Arbutus to safety but

on the 16th, in continued foul weather she foundered and suddenly sank, taking

Oxlade, his number one Lieutenant Charles Stewart RNR and six stokers with her.

The remaining eighty-five crew survived. Another of Bayly’s Q-ships had gone,

its dangerous game lost.

Demise of U-87

Success did attend the sloop Buttercup, however, and on Christmas Day of all days. She was escorting Convoy HD15, Dakar to Liverpool, when the convoy was attacked by U-87 under the command of Freiherr Rudolf von Speth-Schülzburg. Eighteen miles NWN of Bardsey Island in the Irish Sea, U-87 torpedoed the steamship SS Agberi (4,821grt). But von Speth-Schülzburg, on his first cruise in command, stayed too long on the surface. The escorts spotted him and Buttercup, driven at full speed by her captain, Lieutenant Commander Arthur Collier Petherick, rammed into the U-boat; badly damaged, U-87 could not submerge or escape. PC-56, a P-boat built as a Q-ship, was following up behind the sloop and sank the submarine with all hands, forty-four men in total.

On its fifth and final patrol, the U-87 departed

Wilhelmshaven on 8 December 1917 heading to the western end of the English

Channel via the Dover Straits. It sank two small sailing vessels on the way,

and then on Christmas Eve, the 3238ton British steamer DAYBREAK off Northern

Ireland. On Christmas day 1917, the U-87 attacked a convoy in St George’s

Channel (in particular, the 4812-ton British steamship AGBERI, see NPRN

274777). One of the convoy escorts was just 150 yards away from the AGBERI when

it was struck and turned to ram the submarine.

The logbook of HMS BUTTERCUP, an Arabis class sloop,

provides the briefest of overviews of what happened:

02:42 SS AGBERI torpedoed.

03:30 While zig-zagging round AGBERI submarine spotted on

surface. HMS P56 engaged and rammed it. BUTTERCUP fired and hit conning tower.

03:40 SS AGBERI sank. Submarine sank.

05:00 Rejoined convoy.

The Crew listed as lost in U87 are as follows: Adam,

Friedrich; Andermann, Fr; Balleer, Max; Brandt, Johannes; Collinet, Joseph;

Dahlmann, Friedrich; Dethloff, Otto; Dost, Fritz; Faßel, Herbert; Fimpler,

Adolf; Gaßmann, P; Grill, Georg; Hansen, Robert; Heinrich, Freidrich;

Hilgenberg, Karl; Hoffmann, Wilhelm; Hummel, Ernst; Jörgensen, J; Kloß, Karl;

Koppehele, Fritz; Krimme, Otto; Kurth, Jakob; Labahn, Hans; Lehmann, Ernst;

Lehmann, Walter; Ludwig, Edwin; Mrodzikowski, Anton; Patege, August; Petermann,

Hermann; Preisker, Theodor; Reuting, Hermann; Schaff, Paul; Schnellke,

Heinrich; Siebel, Johann; Siebke,

Gustav; Speth-Schülzburg, Rudolf Frhr. V.; Tetmeyer, Robert; Viebranz, R;

Wandt, Kurt; Wille, Wilhelm; Willmer, Hubert; Wodrig, Franz; and Zander, Paul.

U-87 CLASS (1916)

U-87 (22 May 1916), U-88 (22 June 1916), U-89 (6 October

1916), U-90 (12 January 1917), U-91 (14 April 1917), U-92 (12 May 1917)

Builder: Kaiserliche

Werft, Danzig (Werk 31)

Displacement: 757 tons (surfaced), 998 tons (submerged)

Dimensions: 224’9” x 20’4” x 12’9”

Machinery: 2 MAN diesel engines, 2 electric motors, 2

shafts. 2400 bhp/1200 shp = 15.5/8.5 knots

Range: 8000 nm at 8 knots surfaced, 56 nm at 5 knots

submerged

Armament: 6 x 500mm torpedo tubes (4 b o w, 2 stern), total

12 torpedoes, 1 x 105mm gun

Complement: 36

Notes: These submarines represented an important advance on previous Unterseebootkonstruktionsbüro double-hull war mobilization boats, featuring a heavier torpedo armament and improved bow for better sea-keeping. The U-88 was mined off Terschelling on 5 September 1917, and the sloop Buttercup rammed and sank the U-87 in the Irish Sea on 25 December. The cruiser Roxborough rammed and sank the U-89 off Malin Head on 12 February 1918, and the U-92 failed to return from a Bay of Biscay patrol in September. The two surviving boats were surrendered and scrapped.