Having served c. AD180 as legatus of Legio IV Scythica at

Zeugma, Septimius Severus returned to Syria in 194 to confront Pescennius Niger

who had proclaimed himself emperor at Antioch in the previous year. 107 It

seems that the kings of Osrhoene and Hatra had supported Niger, and the

Parthians had taken advantage of the civil war to strengthen their influence in

the region. These were the motives for Severus’ campaigns in Osrhoene and

Mesopotamia, and later against Hatra. Severus took control of Syria quickly and

in 195 successfully campaigned against the Parthians in Mesopotamia where

forces from Osrhoene, Adiabene and the Arabians (probably Hatra) had begun to

besiege Nisibis. It seems that the Edessan king in particular had conspired to

rid the kingdom of Roman control by taking advantage of the civil war between

Septimius Severus and Pescennius Niger. The siege of Nisibis indicates that it

was under Roman military control at this time, but it is difficult to estimate

how much earlier this had taken place.

The result of Severus’ first Parthian campaign was the

conversion of part of the kingdom of Osrhoene into a Roman province and the

retention of a client-kingdom at Edessa based on a much reduced portion of the

former kingdom. Severus prosecuted a second and more significant war against

the Parthians in 197-198 in response to an attack on Mesopotamia in which Nisibis

had almost fallen. Once successful in Mesopotamia, Severus invaded Parthia,

marched down the Euphrates and captured Babylon and Seleucia-Ctesiphon. The

emperor attacked Hatra on his return from Parthia late in 198 or early in 199,

and again in 200; but he was unsuccessful in both cases.

The important outcomes of Severus’ campaigns in the 190s

included the formation of the province of Mesopotamia, the establishment of the

province of Osrhoene and the creation of the dependent kingdom of Edessa.

Important also was the division of Syria into the two provinces of Coele Syria

and Syria Phoenice. The northern half of the old province of Syria constituted

Coele Syria and it was in this new, smaller province that the stretch of the

Euphrates from Samosata to Dura Europos flowed. The city of Palmyra, more

closely linked with the Euphrates through cities such as Dura Europos in Coele

Syria, actually became a part of the province of Syria Phoenice. It has also

been argued recently that the kingdom of Hatra formed an alliance with Rome

soon after the unsuccessful Severan attempts to capture it, but the evidence

for such an alliance is not clear until the 230s.

The province of Mesopotamia occupied the area of northern

Mesopotamia. It lay to the east of the new province of Osrhoene and the client-kingdom

of Edessa, across the Khabur river and as far east as the upper Tigris. The

inclusion of much of the Khabur river in the province of Mesopotamia in the

third century AD is indicated by a papyrus of 245 from a village thought to be

near modern Hasseke, located just to the west of the Khabur. The papyrus is a

petition from a villager to Julius Priscus who is named as Praefectus

Mesopotamiae, indicating that he had jurisdiction over this section of the

Khabur. This is thought to reflect the situation at the time of the province’s

formation 50 years earlier.

The province of Mesopotamia was created by 198 and received

two of three newly raised Parthian legions. Both legions seem to have been

established there after the first war of 194/195, I Parthica at Singara and III

Parthica probably at Nisibis. The coloniae and major cities/fortresses of the

new province were Nisibis, Singara and Rhesaina. The province was governed by a

praefectus of equestrian rank, and its garrison of two legions – the same

number as Coele Syria – demonstrates the military and defensive role it was

designed to play. The formation of the province took Roman administration and a

permanent military presence further east than it had ever been before. It is true

that Trajan had established a short-lived province of Mesopotamia approximately

80 years earlier, and from the mid-160s Mesopotamia perhaps experienced a Roman

military presence, but Severus’ establishment of the province was a long-term

undertaking. According to Dio, Septimius Severus said that he had gained this

territory in order to make it a bulwark for Syria. Dio’s report of Severus’

claim is telling with regard to the longer-term significance of Mesopotamia

following its formation. Increased power and authority in Syria resulted in the

third century. This is the context in which the Roman military presence on the

middle Euphrates and Khabur rivers needs to be considered. Dio was ultimately

critical of the move because Rome had taken control of more territory that had

been traditionally Parthian and this led to the empire becoming even more

embroiled in wars and disputes with its eastern neighbour.

It is difficult to be precise about the territory

encompassed by Mesopotamia as precision seems not to have existed in antiquity.

Roman texts referring to Mesopotamia before the last years of the second

century do not always mention the area that would become the province of

Mesopotamia from Severus’ reign. In the second half of the first century AD,

for example, Pliny the Elder located what he called the Prefecture of

Mesopotamia in the western portion of what was then the kingdom of Osrhoene,

containing the principal towns of Anthemusia and Nicephorium. Singara, which

would form an important legionary base in the province of Mesopotamia under

Septimius Severus and later emperors, was described in the same passage by

Pliny as the capital of an Arabian tribe called the Praetavi. The province of

Mesopotamia in the early third century comprised quite different territory to

the earlier descriptions, but it probably bore similarities to its definition

under Trajan. Lucian of Samosata, however, complained that contemporary writers

in the 160s were so ill-informed about Mesopotamia and where it lay that they

made serious errors in locating it and the cities it contained. Some precision,

however, can be established. The area that comprised the province was focused

on the important cities of Nisibis, Singara and Rhesaina, and part of the

Khabur river lay within the province.

In the years between Septimius Severus’ reorganization of

the eastern provinces and events late in the reign of Severus Alexander, the

most significant developments relevant to Coele Syria, Osrhoene and Mesopotamia

took place in the reign of Septimius Severus’ son Caracalla. In 212/213, the

client-kingdom of Edessa was itself abolished and became part of the province

of Osrhoene, with the city of Edessa becoming a Roman colonia. The provincial

reorganization set in train following the territorial gains of Septimius

Severus was for now complete. There were two provinces across the Euphrates and

one of them lay on a section of the upper Tigris.

In 216, Caracalla, like his father, resolved on a Parthian

campaign. This took him across the Tigris to Arbela before his murder near

Edessa in 217. Caracalla’s short-lived successor Macrinus met with defeat at

the hands of the Parthian king Artabanus V at Nisibis, but Mesopotamia remained

under Roman control. The growing Sasanian challenge to the Parthians was

developing, which may be reflected in the inability of Artabanus to press his

victory in Mesopotamia. It was not until after the Sasanian overthrow of the

Parthians was complete that Roman power in Mesopotamia and on the middle

Euphrates would be seriously challenged.

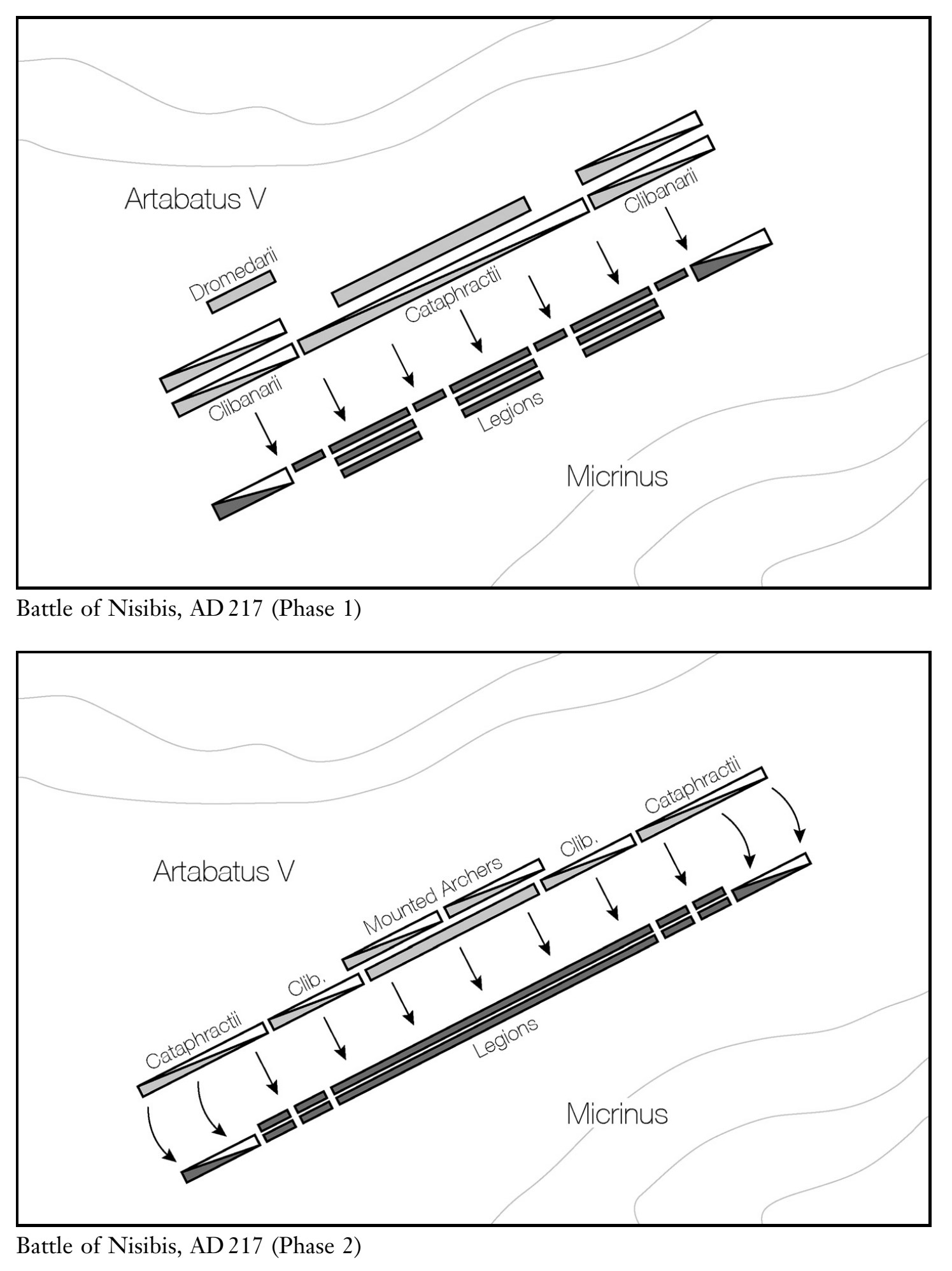

Battle of Nisibis

After Caracalla’s assassination, his successor Macrinus

(217-18) immediately announced that his predecessor had done wrong by the

Parthians and restored peace. In 218, after a battle fought at Nisibis during

which both sides suffered heavy losses, a treaty was signed. According to

Herodian, the Roman emperor Macrinus was delighted about having won the Iranian

opponent as a reliable friend.

Near the city of Nisibis in Mesopotamia, an army led by

Parthian King Artabatus V clashed with the legions of Emperor Macrinus.

Following a skirmish between opposing troops over control of a water source,

the two armies assembled for battle. The Parthian host consisted of large

formations of heavy cavalry – both clibanarii and cataphracti – light mounted

bowmen and a contingent of armoured camel riders called dromedarii. Macrinus

readied his army for battle across the plain: the legions deployed in the

centre, with cavalry and Moorish troops placed on the flanks. Arrayed at

intervals within the central formation were Moroccan auxilia. Once battle was

joined, the Parthian heavy horse and mounted archers inflicted severe

casualties on the Roman infantry, while the legionaries and light troops proved

superior in all hand-to-hand action. As the contest wore on, the Romans found

themselves increasingly at a disadvantage against the speed and manoeuvrability

of the enemy cavalry. In an effort to disrupt these incessant attacks, the

legions feigned retreat at one point so as to draw the horsemen onto ground

littered with caltrops and other devices designed to cripple the horses.

Fighting continued unabated until dusk. Battle resumed the next morning and

lasted all day, but again ended at nightfall with no clear victor. On the third

day, Artabatus attempted to use his superior numbers of cavalry to encircle the

Roman formation by means of a double envelopment, but Macrinus extended his

battle-line in order to thwart the Parthians’ efforts. Toward late afternoon,

the Roman emperor sent envoys to treat for peace, which was readily granted by

the king. Artabatus afterward returned to Persia with his army, and Macrinus

and his forces withdrew to the city of Antioch in Syria. To deter a resumption

of hostilities, Macrinus presented the Parthian ruler with gifts amounting to

200 million sesterces.

Camel Cataphracts

Like most Parthian armies, the forces under Artabanus

consisted mostly of cavalrymen and archers. On the other hand, the Parthian

army at Nisibis was unique in that it contained a contingent of a rare

cataphract–type of warriors who were mounted not upon horses, but rather

camels instead. In his History of the Roman Empire, Herodian first mentions the

distinctive troops in the events leading up to the battle:

Artabanus was marching toward the Romans with a huge

army, including a strong cavalry contingent and a powerful unit of archers and

those cataphracts who hurl spears from camels.

The camel cataphracts fought with either spears or lances,

and both riders and mounts wore extensive armour like the traditional

cataphracts who rode horses. Along with the legionaries, the Roman army also

included contingents of light infantry and Mauretanian cavalrymen. The fighting

between the two ancient superpowers was brutal and lasted for three long days.

Herodian recorded how deadly the Parthian warriors, including the camel

cataphracts, were on the first day of the fighting, yet he also described how

the Romans eventually managed to gain the upper hand:

The barbarians inflicted many wounds upon the Romans from

above, and did considerable damage by the showers of arrows and the long spears

of the cataphract camel riders. But when the fighting came to close quarters,

the Romans easily defeated the barbarians; for when the swarms of Parthian

cavalry and hordes of camel riders were mauling them, the Romans pretended to

retreat and then they threw down caltrops and other keen–pointed iron devices.

Covered by the sand, these were invisible to the horsemen and the camel riders

and were fatal to the animals. The horses, and particularly the tender–footed

camels, stepped on these devices and, falling, threw their riders. As long as

they are mounted on horses and camels, the barbarians in those regions fight

bravely, but if they dismount or are thrown, they are very easily captured;

they cannot stand up to hand–to–hand fighting. And, if they find it necessary

to flee or pursue, the long robes which hang loosely about their feet trip them

up.

However, with the coming of night and no clear victor to the

battle, the two armies retreated to their camps to rest for the night. The

second day of the fighting ended in a stalemate as well. The third day of the

battle, however, decided the outcome when the Parthians changed their tactics

to try and fully envelope the numerically inferior Roman force. In response to

the encircling attempts of the Parthian soldiers, the Romans extended their own

lines to compensate for the extended Parthian front. However, the Parthians

were able to exploit the weakened thinner lines of the Romans and achieve a

great victory. Knowing he had lost the battle, Emperor Macrinus retreated and,

soon after, his men fled to the Roman camp as well. Although the Parthians won

the Battle of Nisibis, it was a Pyrrhic victory for Artabanus; the losses were

heavy for both sides. Since the Parthian emperor desired peace almost as much

as Macrinus, Artabanus accepted only a substantial payment in return for a

cessation of hostilities, as opposed to the territory he previously demanded.

Although Emperor Macrinus was quickly defeated, executed and

replaced by one of his rivals, Elagabalus (r. 218-222), in 218, the Roman

Empire continued to persist for centuries following its defeat at Nisibis. The

Parthian Empire, on the other hand, became even weaker after its conflict with

Rome and continued on its steady decline. Revolts from within the empire

continued to plague Artabanus so he could not sit back and enjoy his success

over the Romans. In 220, the leader of the Persians, Ardashir, managed to break

free from Parthian rule and exploit the weakness of the empire to extend his

control over more and more land. By 224, Artabanus met Ardashir on the field of

battle and lost more than his life; the Parthian Empire collapsed shortly after

his fall. In place of the Parthians, a resurgent Persian state arose known as

the Sassanian Empire. As the new supreme empire of the east, the armies of the

Sassanians had some of the greatest warriors of the ancient world. Like its

Parthian predecessor, the elite heavy cavalry of the Sassanian Empire were also

cataphracts.

MACRINUS, MARCUS OPELLIUS (c. 165-218 A. D.)

Emperor from 217 to 218, and a one-time PREFECT OF THE

PRAETORIAN GUARD under Caracalla, whose death he masterminded. He was born to a

poor family in Caesarea, in Mauretania, and many details of his life have not

been verified, but he apparently moved to Rome and acquired a position as

advisor on law and finances to the Praetorian prefect Plautianus. Surviving the

fall of the prefect in 205, Macrinus became financial minister to Septimius

Severus and of the Flaminian Way. By 212, Macrinus held the trust of Emperor

Caracalla and was appointed prefect of the Praetorian Guard, sharing his duties

with Oclatinus Adventus. Campaigning with Caracalla in 216 against the

Parthians, Macrinus came to fear for his own safety, as Caracalla could be

murderous. When letters addressed to the emperor seemed to point to his own

doom, Macrinus engineered a conspiracy that ended in early 217 with Caracalla’s

assassination near Edessa.

Feigning grief and surprise, Macrinus manipulated the

legions into proclaiming him emperor. To ensure their devotion and to assuage

any doubts as to his complicity in the murder, he deified the martially popular

Caracalla. Meanwhile, the Senate, which had come to loathe the emperor, granted

full approval to Macrinus’ claims. The Senate’s enthusiasm was dampened,

however, by Macrinus’ appointments, including Adventus as city prefect and

Ulpius Julianus and Julianus Nestor as prefects of the Guard. Adventus was too

old and unqualified, while the two prefects and Adventus had been heads of the

feared FRUMENTARII.

Real problems, both military and political, soon surfaced.

Artabanus V had invaded Mesopotamia, and the resulting battle of Nisibis did

not resolve matters. Unable to push his troops, whom he did not trust, Macrinus

accepted a humiliating peace. This, unfortunately, coincided with plotting by

Caracalla’s Syrian family, headed by JULIA MAESA. Macrinus had tried to create

dynastic stability, but mutiny in the Syrian legions threatened his survival.

The Severans put up the young Elagabalus, high priest of the Sun God at Emesa,

as the rival for the throne. Macrinus sent his prefect Ulpius against the

Severan forces only to have him betrayed and murdered. He then faced

Elagabalus’ army, led by the eunuch Gannys, and lost. Macrinus fled to Antioch

and tried to escape to the West but was captured at Chalcedon and returned to

Antioch. Both Macrinus and his son DIADUMENIANUS, whom he had declared his

coruler, were executed.

The reign of Macrinus was important in that it was the first

time that a nonsenator and a Mauretanian had occupied the throne. Further, he

could be called the first of the soldier emperors who would dominate the

chaotic 3rd century A. D. As his successors would discover, the loyalty of the

legions was crucial, more important in some ways than the support of the rest

of the Roman Empire.

NISIBIS

A strategically important city in Mesopotamia, between the

upper reaches of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. Nisibis was for many

centuries the capital of the district of Mygdonia, situated on the Mygdonius River.

Few cities were so bitterly involved in the conflicts between Rome and the

empires of PARTHIA and PERSIA. Any advance into Mesopotamia from Armenia would

aim for the occupation of Nisibis to allow a further attack against the Tigris

or south into Mesopotamia and the Euphrates satrapies. In his campaign against

Parthia, Emperor Trajan captured Nisibis in 114 but then lost it in the revolt

of 116 that killed his general Maximus Santra. The reliable Moor, Lusius

Quietus, was unleashed, and he retook Nisibis as well as EDESSA. Emperor

Septimius Severus suppressed an uprising of the Osroene in 194 and created a

colony at Nisibis, providing it with a procurator. Upon his return in 198,

Severus decreed MESOPOTAMIA a province, with Nisibis as its capital and the

seat of an Equestrian prefect who controlled two legions.

Throughout the 3rd century A. D., Nisibis was buffeted back and forth as Rome and Persia struggled against one another. Following the crushing defeat of King NARSES in 298, at the hands of Emperor Galerius, Nisibis enjoyed a monopoly as the trading center between the two realms. In 363, Julian launched an unsuccessful Persian expedition; his successor Jovian accepted a humiliating peace with SHAPUR Nisibis became Persian once again.