It was now mid-afternoon and, despite the carpet of dead,

dying and wounded covering the lower half of the slope, Dargai Heights still

remained firmly in enemy hands. The crisis of the battle having been reached,

Yeatman-Biggs ordered Kempster to commit the Gordons and the 3rd Sikhs, his

last reserves. The latter were providing an escort for the guns on a lower spur

and had to await relief by a Jhind state infantry battalion, but the Gordons

moved off at once.

As they clambered up the narrow path they were not

encouraged by the steady stream of dead and wounded being carried past in the

opposite direction. At length they formed up in dead ground screened by some

low scrub at the lower edge of the slope. Nearby, grim-faced Derbys, Dorsets

and Gurkhas lay firing at the enemy, now capering among the rocks and yelling

derisive insults.

It is a matter of record that Highland infantry, heirs to a

long and violent history in which the carrying of arms and settlement of

disputes by force was usual, have always launched their attacks with a unique

speed and a berserk ferocity that was very difficult and often impossible to

stop. Colonel Mathias knew how best to awaken these qualities in his men and,

having been told that his assault would be preceded by three minutes’

concentrated artillery fire on the summit, he used the

interval to address them very briefly, his voice cutting like a whiplash

through the sounds of gunfire, musketry, savage drumming and yells:

The General says this hill must be taken at all costs – the

Gordon Highlanders will take it!’

There was a moment’s silence. The men knew the terrible

risks involved, but the Colonel had given his word on their behalf and not one

of them would let him down.

‘Aye!’ It was a spontaneous roar from 600 throats.

‘Officers and pipers to the fore!’

It was now, as the sun glinted on the officers’ drawn

broadswords and the Pipe Major took his place, throwing his plaid and drones

across his shoulder with infinite swagger, that the inherited instincts of

countless bloody if long-forgotten clan battles began to surface, causing the

scalp to crawl and the hackles to rise. Like their forebears of old, they, led

by their chief men and pipers, were going out to meet the enemy, steel to

steel. Suddenly, the supporting gunfire ceased.

‘Bugler – sound Advance!’

Like a tidal wave the Gordons poured out of cover and onto

the deadly open slopes. The pipers struck up the regimental march, The Cock o’

the North,3 a fine ranting tune that skirled across the hillside, evoking a

response from every man present. Yelling, the entire battalion swept upwards.

Mathias, still up with the leaders, had unleashed the full fury of his Gordons

and knew that they would give the shortest shrift to anyone who got in their

way.

Perhaps the sudden appearance of the battalion caught the

enemy unawares. If so, the respite was only of seconds’ duration. Once again,

the crest blazed with fire and, once again, the dust was stirred into a fine

mist by the pelting hail of bullets. And now the Gordons began to go down.

Lieutenant Lamont was killed outright at the head of his men. Major Macbean,

shot through the thigh, crawled to a boulder and continued to cheer on the

assault. Lieutenant Dingwall, hit in four places and unable to move, was

carried to safety by Private Lawson, who then returned to bring in the wounded

Private Macmillan, being hit twice while doing so. The pipers, who could

neither run nor take cover and still play, continued to walk upright and thus

became a special target for the enemy. Lance-Corporal Milne, among the first to

set foot on the slope, continued to march upwards until shot through the chest.

Piper George Findlater suddenly felt his feet knocked from under him by a sharp

blow. Sitting up, he discovered that he had been shot through both ankles but,

disregarding alike the enemy’s fire, the pain and the fear that he might never

walk normally again, he continued to play his comrades into action. Mathias was

hit but kept moving. Major Downman got a bullet through his helmet. Other men

felt rounds twitching at their kilts and tunics. Major Macbean, reaching for

his water bottle after the assault had passed by, found it empty save for the

bullet responsible for draining the contents.

It took less than two minutes for the leading companies to

reach the ledge where the Gurkhas were sheltering, although it seemed far

longer. There they paused briefly to get their breath back while the others

closed up. Then, with a wave of the broadsword and a sharp shout of ‘Come!’ the

officers led a second rush across the ledge to the foot of the escarpment. This

time the Gordons were accompanied by kukri-wielding Gurkhas, keen to exact

payment for the long hours they had spent pinned down. Another pause, and then

the Gordons were scrambling up the goat paths towards the summit. Already the

enemy’s triumphant drumming had stopped and his firing become ragged.

Instinctively the tribesmen understood that the green-kilted soldiers could not

be stopped and, recognising the murder in their attackers’ eyes, they began

shredding away. Those with a mind to stay quickly changed it when, far below,

they saw the 3rd Sikhs crossing the open slope, big, bearded, turbaned men

coming steadily on behind a line of levelled bayonets. There were, too, large

numbers of Dorsets, Derbys and Gurkhas who, inspired by the Gordons’ assault,

were rushing forward to join in the attack.

Thus, when the Gordons finally reached the summit, they

found the sangars contained only a handful of dead and wounded. The reverse

slopes of the spur, however, were black with the running figures of thousands

of tribesmen, into whom a rapid fire was opened, sending many tumbling among

the rocks.

Mathias, out of breath and bleeding, reached the summit

alongside Colour Sergeant Mackie.

‘Stiff climb, eh, Mackie?’ he remarked. ‘I’m not quite so

young as I was, you know.’

‘Och, never you mind, sir,’ replied the colour sergeant,

slapping his commanding officer on the back with a familiarity justified by

events, ‘Ye were goin’ verra strong for an auld man!’ If the compliment was

unintentionally back-handed, the admiration was genuine, as Mathias found when

his Gordons, now laughing and joking, gathered round to give him three cheers.

Yeatman-Biggs was determined that the tribesmen would not be

given a second chance to reoccupy the heights and detailed the Gurkhas and the

Dorsets to hold them. The Gordons volunteered to carry down their wounded, an

act of kindness that was greatly appreciated. Afterwards, as they marched to

their own bivouac, each regiment they passed broke into spontaneous cheering,

officers and men pressing forward to shake their hands and offer their water

bottles, a small gesture but a very generous one considering that no further

supplies could be obtained until the following day.

As the Widow of Windsor’s parties went, the second capture

of Dargai Heights was small in scale but it was as bitterly contested as any.

The cost was three officers and 33 other ranks killed and twelve officers and

147 other ranks wounded, the majority of these casualties being incurred on the

lowest 150 yards of the open slope. The Gordons’ share amounted to one officer

and six other ranks killed and six officers and 31 other ranks wounded. In the

circumstances this was little short of astonishing but can be attributed to the

speed with which the attack was delivered across the most exposed portion of

the open slope, this being cited in later tactical manuals.

Mathias was to receive many congratulatory telegrams on

behalf of his battalion; from the Queen and from the British Army’s

Commander-in-Chief, Field Marshal Lord Wolseley, from the Gordons’ 2nd

Battalion, from the regiment’s friendly rivals the Black Watch, and from Caledonian

societies all over the world, including the United States.

Yeatman-Biggs recommended that the Victoria Cross be awarded

to Lieutenant-Colonel Mathias, Piper Findlater and Private Lawson. In Mathias’

case the supreme award was denied, thanks to an incredibly priggish decision by

the War Office that neither general officers nor battalion commanders were

eligible for the Cross, presumably because they were doing nothing less than

their duty.4 Queen Victoria made her own feelings known in no uncertain manner

by promptly appointing him as one of her aides de camp with the rank of

colonel, although he continued to command the battalion until its return to

Scotland the following year. Piper Findlater5 and Private Lawson received the

award in the field. In addition, Colour Sergeants J. Mackie and T. Craib,

Sergeants F. Ritchie, D. Mathers, J. Donaldson and J. Mackay, and

Lance-Corporal (Piper) G. Milne were awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal,

the last mentioned being decorated personally by the Queen when he was

invalided home.6

The Tirah Field Force fought many more battles as it

penetrated deeper into tribal territory, but none was as fiercely contested or

as critical as Dargai. Early in November it reached its objective, the Tirah

Maidan, a beautiful, fertile valley one hundred square miles in extent, flanked

by pine-clad slopes and dotted with copses. There were numerous houses, each of

which, significantly, was fortified against its neighbours. In the storerooms

were piled high the fruits of the recent harvest – Indian corn, beans, barley,

honey, potatoes, walnuts and onions. The entire valley was deserted, the

inhabitants having taken their families with them into the hills. Lockhart

despatched columns into every corner of the Tirah, where the resistance

encountered clearly indicated that the tribes had no intention of submitting.

Reluctantly, he decided that if they would not talk he would begin laying waste

the valley. The troops, many of whom came from farming stock, did not enjoy the

work, but the sight of groves being felled and columns of smoke rising from

burning buildings produced the desired result. With the exception of the

ungovernable Zakha Khel, who did not submit until the following April, the

tribes sent in their leaders to a jirga where they accepted their punishment:

they would give up 800 serviceable rifles, pay a fine of 50,000 rupees and

return all the property they had stolen during the rising. On 7 December, with

the worst of the winter snows approaching, the evacuation of the Tirah Maidan

began. The withdrawal of the 1st Division was comparatively uneventful, but

that of the 2nd Division was subject to constant ambushes and attacks that

inflicted 164 casualties and were obviously not the work of the Zakha Khel

alone. Nevertheless, so thoroughly had the rising been put down that during the

next twenty years only five major punitive expeditions were required to police

troublesome areas, and never again was fighting so widespread along the

Frontier.

It would be absurd to suggest that any love was lost between

the British and the tribes, but there was a great deal of mutual respect and

during both World Wars thousands of the latter volunteered for service with the

Crown. There was even a sense of loss when the British left India, for now no

one remained for their young men to prove themselves against, even their

hereditary Hindu enemies having been removed far to the south of them by the

creation of the Islamic state of Pakistan. Yet the world was to hear of them

again, for when the Soviet Union launched its disastrous occupation of

Afghanistan in 1979 the Frontier again became an arsenal and huge numbers

crossed to fight alongside their co-religious kindred in the Mujahideen. For

all its size, the Soviet Army was unable to cope. In the end, therefore, the

mullahs’ promise of a successful jihad had been fulfilled, albeit a century

after it was made and against a very different kind of infidel.

Notes

1. Kempster had an unfortunate personality and was so

unpopular throughout the Tirah Field Force that its members coined the verb ‘to

be kempstered,’ that is, generally mucked about. For all that, he was a capable

enough officer in action.

2. Later the Sherwoood Foresters.

3. The Cock o’ the North was the nickname of the Duke of

Gordon who had raised the regiment 104 years earlier.

4. At the time the Victoria Cross warrant also incorporated

a clause to the effect that in the event of subsequent ‘scandalous conduct’ the

award would be forfeit. This rarely happened but when it did there was an

understandable public outcry in protest. King Edward VII put an end to this

sort of sanctimonious humbug.

5. To quote from a footnote in Chapter 26 of the Gordon

Highlanders’ regimental history, The Life of a Regiment: The incident of the

wounded piper continuing to play, being telegraphed home, took the British

public by storm, and when Findlater arrived in England he found himself famous.

Reporters rushed to interview him; managers offered him fabulous sums to play

at their theatres; the streets of London and all the country towns were

placarded with his portrait; when, after his discharge, he was brought to play

at the Military Tournament, royal personages and distinguished generals shook

him by the hand; his photograph was sold by thousands; the Scotsmen in London

would have let him swim in champagne, and the daily cheers of the multitude

were enough to turn an older head than that of this young soldier. A handsome

pension enabled Findlater to rest on his laurels and turn his sword into a

ploughshare on a farm near Turriff. He re-enlisted for the Great War, though

not fit for foreign service.’

6. Throughout their subsequent history the Gordon

Highlanders celebrated the anniversary of Dargai wherever they were stationed.

Thanks to government economies that have reduced the Army’s strength to the

lowest level for 300 years, the regiment no longer has an independent

existence, having merged with the Queen’s Own Highlanders to form a new

regiment, The Highlanders (Seaforth, Gordons and Camerons). This will, however,

continue to celebrate the anniversary of the action.

Tirah Field Force (1897-1898)

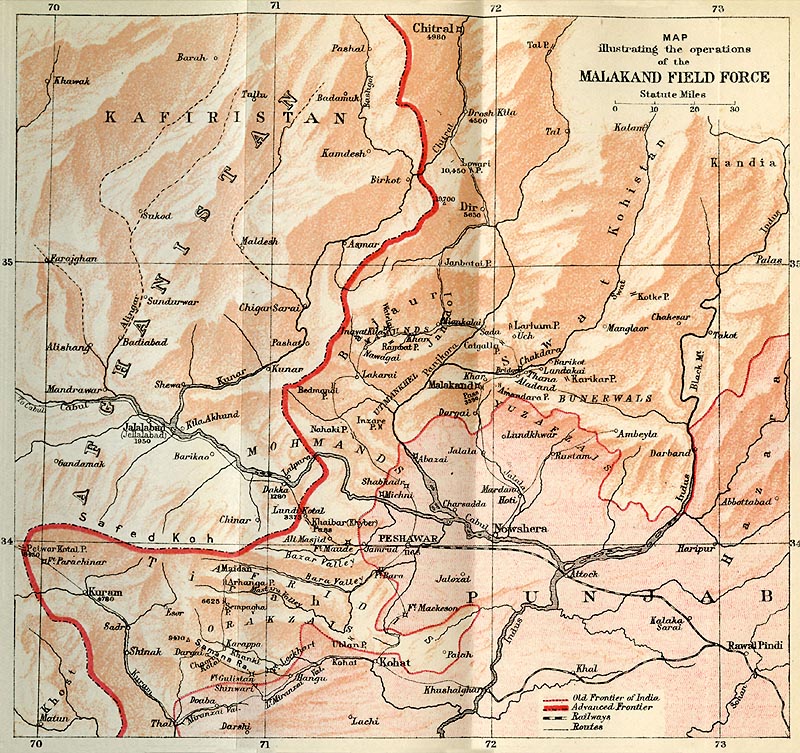

The North – West Frontier of India was ablaze in Pathan

tribal hostilities in 1897. The British sent many punitive expeditions to

suppress these tribal revolts. The Tochi Field Force was sent to quell the

Isazais in the Tochi Valley, and the Mohmand Field Force was organized to

suppress hostile Mohmands. The Malakand Field Force conducted operations

against the Swatis, Utman Khel, Mamunds, and Salarzais, and the Buner Field

Force punished the rebellious Bunerwhals.

The Afridis had been receiving a subsidy from the Indian

Government for many years to safeguard the strategic Khyber Pass. On 23 August

1897, hostile Afridis and Orakzais attacked and seized the forts at the Khyber

Pass. Four days later, Orakzais attacked in overwhelming strength the British

posts on the Samana Ridge, about 30 miles south of the Khyber Pass and the

southern boundary of the Tirah region, and close to Peshawar.

To punish the rebellious tribes and dis courage any further

hostilities to the south, especially in Waziristan, it was decided to form the

Tirah Field Force and invade Tirah, the homeland of the Afridis and Orakzais.

It was initially difficult to assemble a sufficient number of men due to other

ongoing punitive operations. On 10 October 1897, however, under the command of

General Sir William S. A. Lockhart, the Tirah Field Force was assembled at

Kohat and prepared to advance. Numbering 34,506 British and Indi an officers

and troops, with 19,934 noncombatant followers and 71,800 transport animals,

the Tirah Field Force was the largest British Army expedition to deploy to the

field in India since the Indian Mutiny.

The Tirah Field Force consisted of two divisions, plus

support and reserve elements. The 1st Division was commanded by Major General

W. P. Symons, with its 1st Brigade commanded initially by Colonel (later

General Sir) Ian S. M. Hamilton, then by Brigadier General R. Hart, V. C., and

the 2nd Brigade commanded by Brigadier General A. Gaselee. Major General A. G.

Yeatman – Biggs commanded the 2nd Division, which consisted of Brigadier

General F. J. Kempster’s 3rd Brigade and Brigadier General R. Westmacott’s 4th

Brigade. The lines of communication were commanded by Lieutenant General Sir A.

P. Palmer, and the Rawalpindi Reserve Brigade by Brigadier Gener al C. R.

Macgregor. There were also two mobile columns (the Peshawar Column , commanded

by Brigadier General A. G. Hammond, V. C., and the Kurram Movable Column, by

Colonel W. Hill) to provide flank security and support. Support elements

included 10 field and mountain artillery batteries, totaling 60 guns, and the

first machine- gun detachment deployed to the North- West Frontier.

The Tirah Field Force strategy was to advance north,

subjugate the Tirah region, then move farther northeast to recapture the Khyber

Pass. The Tirah area, however, was basically unknown to the British, and the

combined strength of the Afridis and the Orakzais was estimated at around

40,000-50,000.

The British advance began on 11 October 1897. Seven days

later, routes over the Samana Ridge were reconnoitered, and fighting broke out

almost immediately. The 5,000-foot high Dargai Heights, key terrain dominating

the area, were seized by the British on 18 October with casualties of 10 killed

and 53 wounded. It was decided not to hold the Dargai Heights and the British

evacuated the position.

After more units and supplies, including ammunition, had

arrived, the Dargai Heights were again attacked on 20 October 1897. The Pathans

had reinforced their positions on the Heights, and a British artillery barrage

failed to dislodge the tribal warriors. Gurkhas led the attack, but were pinned

down by accurate rifle fire. At about noon, the 1st Battalion, Gordon

Highlanders- with bayonets fixed and the regimental bagpipes playing “Cock

o’ the North” – led a five battalion assault. Before the British reached

the summit, the tribesmen fled. The second capture of Dargai cost the British

36 killed and 159 wounded, and was the only set – piece battle of the campaign.

A pause in the hostilities ensued as the 1st Division and

transport, traveling on bad roads, rejoined the leading 2nd Division. The

advance continued on 28 October 1897, and the next objective was the 6,700-foot

Sampagha Pass. The Tirah Valley was reached after little resistance on 1

November 1897. The following eight days were spent gathering supplies and

reconnoitering the area. The Orakzais were showing signs of submission although

there was constant harassment and sniping from the Zakha Khel, a powerful

Afridi clan. Lockhart retaliated by launching a scorched earth campaign,

leveling villages, destroying crops, and felling orchards. On 11 November,

Orakzais tribal chiefs agreed with peace terms to return all captured weapons

to the British, surrender 300 of their own breech – loading rifles, pay a

30,000 rupee (£10,000) fine, and forfeit all allowances and subsidies.

British units continued operating to eliminate resistance

throughout November 1897, but the Zakha Khels engaged in frequent hit – and –

run engagements, especially against vulnerable support and transport elements.

The Afridis, as a tribe, had not submit ted fully to the British, but with the

approach of winter, the British began their 40-mile march through the Bara

Valley to the Khyber Pass on 7 December 1897. Each division marched on a

separate route. In snow and frigid temperatures, the British continued. The 2nd

Division was harried the entire way and fought numerous rear- guard actions.

The British march “looked more like a rout than the victorious withdrawal

of a punitive force”(Miller 1977, p. 279).After having been separated, the

Tirah Field Force’s two divisions converged at the Indian frontier town of

Barkai on 14 December.

Lockhart did not feel he had totally accomplished his

mission. On 22 December 1897, the 1st Division marched to the Bazar Valley, the

home of the Zakha Khel, and the Peshawar Column advanced to the Khyber Pass.

(This latter operation is frequently called the Bazar Valley Expedition.) By 1

January 1898, three British brigades held the Khyber Pass, while two additional

brigades blockaded the Afridi territory. The British fought a few engagements

and destroyed Afridi villages and captured Afridi cattle and sheep. The last of

the Afridi clans submit ted to British demands in April 1898, signaling the end

of the Great Pathan Revolt. From 12 October 1897 to April 1898, the British

suffered 1,150 total casualties (287 killed, 853 wounded, and 10 missing).

Battle of Saragarhi

The Punjab Frontier Force was set up and comprised the 1st,

2nd (Hill), 3rd and 4th Regiments of infantry as well as cavalry units. Acting

primarily as rapid-response regiments, they would patrol the British borders in

search of any Afghan aggression. The Sikhs displayed great bravery during the

war and were employed effectively at both Ahmed Khel and Kandahar towards the

end of the conflict in 1880. Their courage and dedication was admired by the

British and would be utilised to greater effect in future campaigns.

A British victory came in 1880, but the war was now more

than just an Anglo-Afghan affair, as Russia waded into the conflict. A period

known as the `Great Game’ was initiated, and in what has been known since as

the `Cold War of the 19th century’, the two powers sidestepped each other

without ever locking horns. To stabilise their forces, the British raised two

more Sikh regiments, the 35th and the 36th, who would see battle in the next

big conflict in the region, the Tirah Campaign.

The war was almost inevitable. In the face of further

British expansion during the Great Game, the empire became tangled up in issues

with various local hill tribes. Although rarely united, they put their forces

together against the British in what became known as the Tirah Expedition. As a

result, the British lost a fair amount of land in the north west including the

strategically important Khyber Pass. With access to the pass now in Afghan

hands, the security of the British Raj was in jeopardy. Up to 40,000 soldiers

were called into the area including many Sikhs, who were keen to put their

skills to the test after being marginalized from the main army in the previous

Anglo-Afghan War. After initial assaults by the Gurkha and Highland regiments,

the Sikhs were called in to supplement the Highland charge on the bloody but

successful Dargai Heights.

Undoubtedly the greatest Sikh achievement of the war was the

Battle of Saragarhi. A backs-to-the-wall conflict of Thermopylae proportions,

21 Sikh soldiers managed to defend a small outpost from 10,000 tribesmen for

more than seven hours. Despite receiving no aid from any of the surrounding

British forts, the 36th Sikhs Regiment fought courageously and, even in defeat,

managed to blunt the Afghan assault for long enough to save the two forts of

Gullistan and Lockhart. To this day, Saragarhi Day is celebrated annually in

honour of this heroic sacrifice and each of the 21 received the Indian Order of

Merit posthumously.

The main British Field Force was now in the ascendancy, but

guerilla warfare was taking its toll on the beleaguered soldiers. In November

1897, a unit from the Northamptonshire Regiment was going through a village in

the Saran Sar Pass when it came under heavy fire. In the end, the group had to

be saved and extracted by a combination of Sikhs and Gurkhas, who managed to

haul the British out of harm’s away with only 18 men killed.

The terrain and local knowledge of the Afghans even made

life difficult for the impressive Sikhs, who were ambushed while on the hunt

for straggling Afridis, one of the many Afghan tribes. Along with two companies

from the Dorset Regiment, the Sikhs were cornered in a number of burned-out

houses before making it to safety. 25 men and four officers were killed. The

next move of the expedition was to starve the Afghans of their winter food

supplies. Accompanying the Yorkshire Light Infantry, the 36th Sikhs made a

grave error and, after a misunderstanding, abandoned the strategically valuable

heights to the west of a pass. Their position was taken up by a group of

Afridis, who inflicted casualties on the men from Yorkshire, forcing them to

escape with the aid of a relief column.