Antoine de Marbot recounted an incident that demonstrated

the properties of the two styles of cuirass, when at Eckmühl in April 1809

French and Austrian cuirassiers crashed together, while the accompanying light

cavalry drew off to the flanks to avoid being caught up in the fight.

The cuirassiers advanced rapidly upon each other, and

became one immense melée. Courage, tenacity and strength were well matched, but

the defensive arms were unequal, for the Austrian cuirasses only covered them

in front, and gave no protection to the back in a crowd. In this way, the

French troopers who, having double cuirasses and no fear of being wounded from

behind had only to think of thrusting, were able to give point to the enemy’s

backs, and slew a great many of them with small loss to themselves. [When the

Austrians wheeled about to withdraw] the fight became a butchery, as our

cuirassiers pursued the enemy. This fight settled a question which had long

been debated, as to the necessity of double cuirasses, for the proportion of

Austrians wounded and killed amounted respectively to eight and thirteen for

one Frenchman.

A further item of protective equipment used by heavy

cavalry was a consequence of the knee-to-knee charge formation: the long boots

worn to prevent the legs being crushed. Some thought them more an encumbrance

than a protection, as Marbot observed of a dismounted cuirassier officer at

Eckmühl who was unable to run fast enough to escape the enemy – he was killed in

the act of pulling off his boots

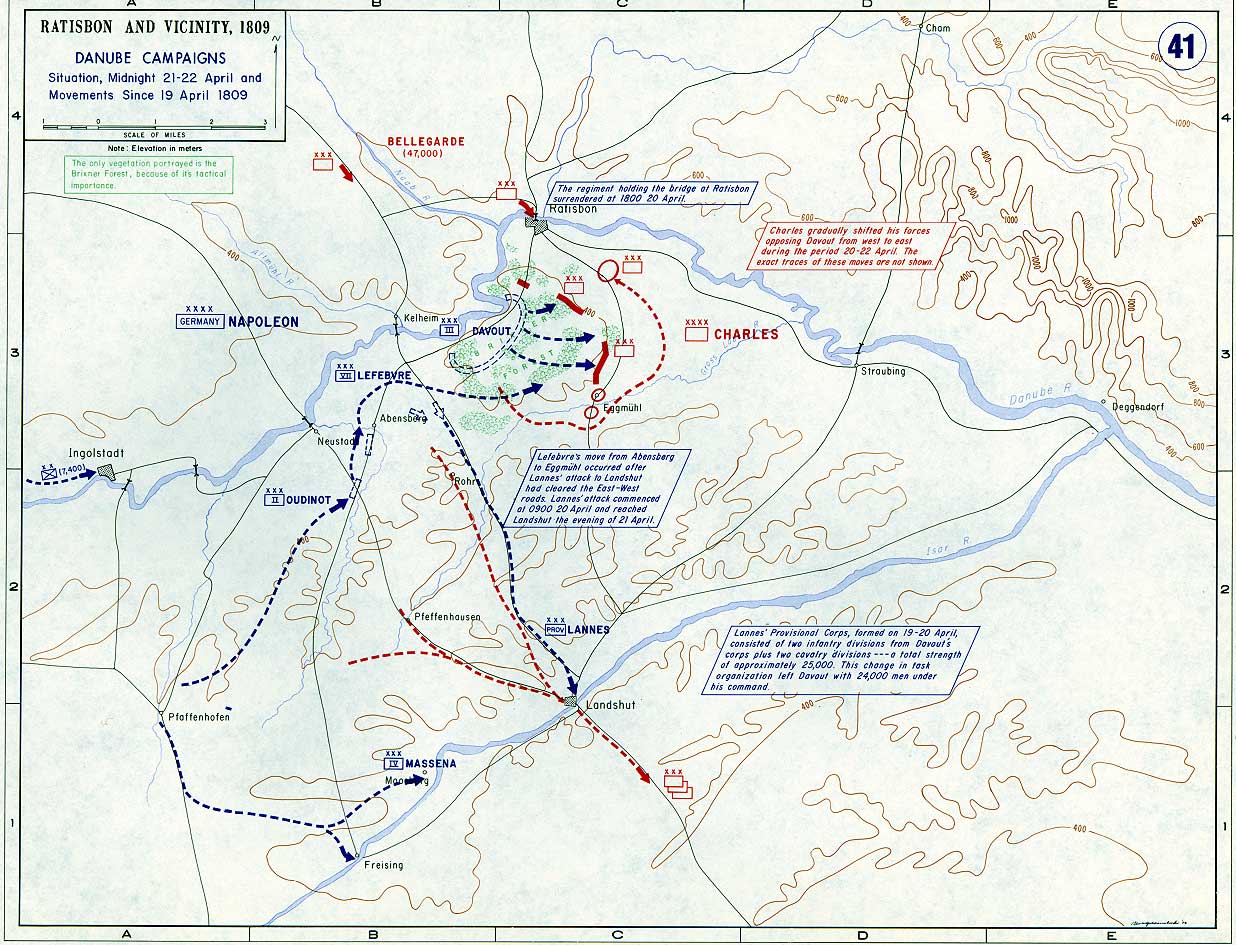

At Landshut one of the Archduke’s Corps (V) attacked a

strong force of Bavarians, driving it from the town, before turning to attack

an isolated French force under Davout occupying Regensburg. Unfortunately, the

Archduke had discovered too late that Davout was unsupported. While Archduke

Charles pulled back, having failed to destroy Marshal Louis Davout’s III Corps

during the action at Teugn-Hausen on 19 April, Napoleon launched his

counteroffensive on the following day, splitting the Austrian army in two.

Napoleon pursued what he erroneously believed was the main force southward

toward Landshut, leaving Davout and Marshal François Lefebvre to deal with what

he perceived as an Austrian rear guard. However, on 21 April, as Davout closed

in on the village of Eckmühl, he realized that he faced a much stronger force.

Despite this Davout attacked, but a tenacious Austrian defense held firm.

Archduke Charles could have been crushed 24 hours earlier,

but Napoleon had now arrived. With his arrival, the uncoordinated and disparate

French forces began to take on some cohesion. But even Napoleon misread what

was happening. He did not realise until it was almost too late that Davout was

facing most of the Archduke’s army.

Davout sent Napoleon a number of messages during the day

expressing his concerns, but it was only in the early hours of 22 April that

Napoleon finally recognized his error.

As soon as he saw his mistake, his legendary skills of

improvisation took hold immediately. Davout was supported by the bulk of Napoleon’s

forces and a concerted effort was made to break the Austrian left, which was

sheltering behind a battery of guns. Prince Rosenberg and his staff of IV Korps

watched for two hours while 22 Austrian battalions held out against

overwhelming numbers until 68 French battalions attacked them on three sides.

As Napoleon committed his cavalry, Rosenberg’s retreat degenerated into a rout.

Repeatedly he had asked Charles for reinforcements but repeatedly Charles had

advised him to extricate himself as best he `thought fit’. The Archduke had no

intention of sacrificing fresh troops on ground not of his own choosing.

Nevertheless, seeing panic taking hold among Rosenberg’s

men, Charles immediately deployed a Cuirassier brigade and his Grenadier

Reserve under Rohan to stem the tide. The Austrian cavalry slowed the French

advance, forcing the infantry to form squares, but Rohan’s grenadiers with the

exception of two battalions broke under the tide of IV Korps’s demoralised

remnants. IV Korps was facing annihilation as a heavy mass of French

cuirassiers approached to finish off its survivors.

It was 7 p. m. and the rising moon illuminated a dramatic

scene. Six thousand French cuirassiers in two lines supported by their

Württemberg and Bavarian auxiliaries advanced towards two much thinner lines of

Austrian cuirassiers supported on their flanks by some squadrons of hussars.

The tired French horsemen trotted forward while the Austrians with the gradient

in their favour galloped towards them, about to break into a charge. As there

were five French regiments against just two Austrian, this fight could only

last a few moments and the Austrians were soon riding as fast as they could

back to their lines. Two battalions of Austrian grenadiers appeared and formed

square but were cut to pieces by St Sulpice’s Cuirassiers. The Archduke Charles

himself escaped only with the greatest of difficulty. Exhaustion on the part of

the French, and darkness, rescued the Austrians from annihilation. Charles

however could take some consolation from the fact that he had husbanded his

forces and he had not even committed 33,000 of his troops.

Thus ended the Battle of Eckmühl; unsatisfactory for

Napoleon, who had not deployed his characteristic ruthlessness to inflict a

`second Jena’ and highly unsatisfactory for the Archduke Charles, who had seen

his elite units fail to rise to the occasion, though they had bought him the

time necessary to effect an escape from the clutches of his foe.

In fact Charles’s position at this stage was stronger than it

appeared. Eckmühl was a rearguard action fought by Rosenberg against a greatly

superior enemy attacking him from the west, south and east. Two Austrian Korps,

I and II, were far from demoralised and the Generalissimus still had his lines

of communication with Vienna, though these now ran through Bohemia. True, II

and IV Korps had been defeated and had retired in poor shape, but they had not

been completely crushed. On the morning of 23 April Charles wrote to his brother,

the Emperor, advising him to leave Schärding where he was awaiting results and

not rely on the Archduke to be able to save either him or Vienna.

While Napoleon paused, Charles got most of his army across

the Danube, leaving a small force to withstand the siege that was inevitable

the following day when the French invested Regensburg. It was here that

Napoleon received his only known wound in twenty years of making war, when a

spent cannonball hit his foot. Napoleon’s failure to pursue Charles has been

attributed by the renowned French military historian General H. Bonnal to his

dwindling grasp of the strategic imperative to destroy his opponents. His

Bavarian campaign involved his forces in three battles in as many days but each

time Charles was able to withdraw in reasonable order. As the Austrians had

lost two- thirds of their artillery the question rightly arises as to what

might have happened had the French cavalry pursued them `epée dans les reins’.

But Napoleon later admitted to Wimpfen that he never imagined the defeated

Austrians would rise like a phoenix from the ashes within weeks.

Retreating across the Danube at Regensburg, the Austrian

army marched through Bohemia to link up with the left wing of the army arriving

from Landshut. The French advanced and occupied Vienna on 13 May. Eight days

later the reunited Austrian army engaged Napoleon once more at the Battle of

Aspern-Essling.