The volume of incoming fire grew; neither the aircraft nor

the naval fire support had an answer for what the Japanese had installed on

Saipan’s reverse slopes. “There was a loud explosion to our right,” Robert Graf

wrote, “and we saw one of our craft exploding, bodies flying through the air.”

Carl Roth said, “Unlock your pieces. Good luck. Keep low,

and get inland as fast as you can and get off the beach. They’re zeroing in on

it.” Turner had overestimated the threat of beach defenses—pillboxes with

machine guns, fire trenches, antitank trenches, and the like. Artillery and

mortars located inland were the problem. He had underrated them. The clouds

obscuring the early reconnaissance photos hid the guns from Nimitz’s analysts.

They revealed themselves against the first waves.

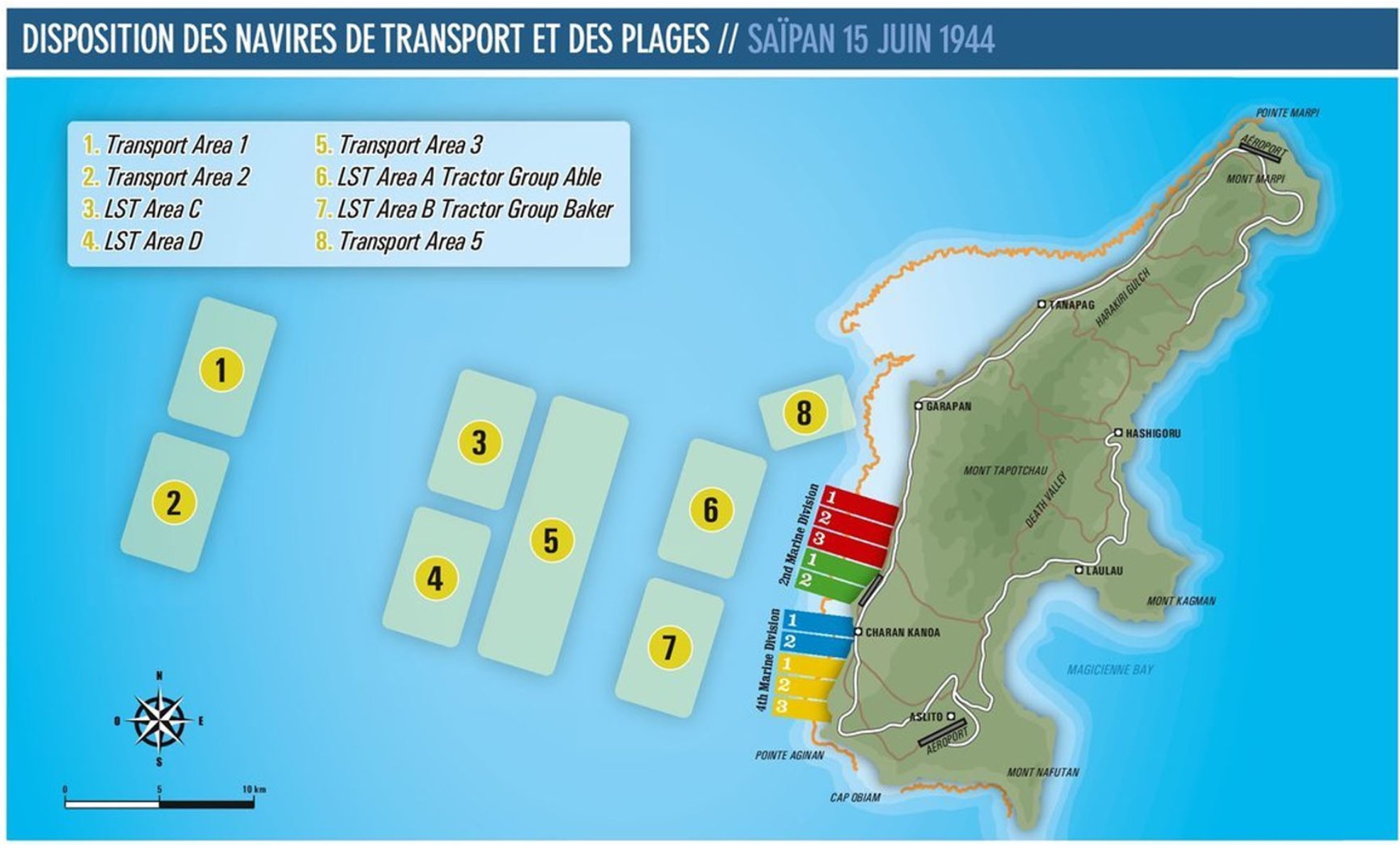

Control officers off Blue and Yellow beaches reported the

first waves of the Fourth Marine Division ashore at 8:43. Five minutes later an

air observer reported the Second Marine Division’s amtracs piling onto Red and

Green beaches, though not always in the right place. Heavy fire poured into the

first wave from the shrub-topped bluff behind Red Three. Heavier fire enfiladed

them from Afetna Point, far to the right. The volume of it startled the

drivers, and even the slightest flinch at the wheel caused them to veer left,

carrying in the Sixth Marines farther north than they were supposed to be. The

same problem beset the Eighth Regiment, only worse, owing to a

northward-carrying tide. Both of its battalions landed on Green One, causing

congestion and a dangerous massing of forces there, as well as a void on Green

Two, just to the south. The architect of the Second Marine Division’s confusion

was a battery of heavy machine guns and antiboat guns on Afetna Point. Having

somehow survived the morning bombardment by the Birmingham and Indianapolis, it

enjoyed a run of terrible glory. Head still down, filled with silent prayer,

Robert Graf heard the smooth tenor of the engine change as his tracks bit into

the ground. His platoon was on the beach.

As the critical hour began ashore, the naval fire support

shifted inland, leaving the amtracs to their own devices. The bow gunners

trained their fifties on the thin ribbon of sand and scrub ahead as the mortars

and artillery continued their incessant high-angle fall. General Saito’s

artillerymen and mortar teams were in impressive form given the plastering that

had been leveled upon them from air and sea. Lofting shells on tall parabolas

from crevices, ravines, and the back sides of hills, they began taking a toll

on Turner’s force. The beach where Easy Company of the 2/23 went ashore, Blue

Beach Two, took a particularly brutal deluge. “More and more shells came

pounding at us and more tractors were hit,” wrote Graf. “Bodies, both whole and

in pieces, were scattered about.” He saw men mortally wounded but still alive,

floating with the aid of life jackets. The Marines left no man behind, except by

necessity at H Hour, when the imperative to get off the beach was existential.

The whole operation depended on it. Already, with the arrival of the second

wave, the boat lane was a bottleneck, with a huge inflow of machines grinding

through it.

Amtracs had their appeal, foremost their armor plate, which

was proof against all but the closest artillery rounds. But many veteran

Marines preferred the old LCVPs with their bow ramps, which when dropped

allowed them to make a quick low rush forward out of the hold. Amtracs, in

contrast, required them to stand up and dismount over the side, and that meant

exposing themselves to enemy fire. When Donald Boots hit the beach, enemy

gunners were waiting. The platoon sergeant and gunnery sergeant of his pioneer

company were shot dead along with a few other men. As bullets zipped overhead,

his platoon, deprived of their leadership, dropped to the beach and pressed

themselves into the crushed coral for cover. Boots moved left, bounding into a

large shell crater with several other men as machine gun fire whipped overhead.

When the mortars came, Boots didn’t think he would survive.

“It was really tragic to watch the effect of this mortar

fire on our own troops,” said Captain Inglis.

The Japanese were extremely accurate, and as they walked

this shellfire up the beach, this shellfire falling at about ten yard

intervals, our Marines at first stood up under the fire without flinching,

continued their operations of sorting out and transporting to front lines the

equipment which had been landed and which was lying on the beach. After the

first two or three shells had fallen it was quite apparent to us that the

Marines were beginning to flinch under the fire and at first they threw

themselves on the ground and then eventually, after this fire was continued,

broke and ran. Through high powered optical instruments we could almost see the

whiskers on men’s faces, and the whole impression that I received was something

unreal, something that you might see in the London Graphic, for instance, as

sketched in the imagination of an artist. It seemed almost too dramatic and too

close to be realistic.

Though the largest Japanese coastal guns had been easy for

the Navy to destroy, as they were sited conspicuously in fixed emplacements

vulnerable to direct fire, and beach positions evaporated quickly in the

initial barrage, the inland positions were trickier even when ship commanders

could see where the fire was coming from. “The mobilization of that mass of

field artillery and mortars on the reverse slope of the hills back of the

beaches was a complete unknown to us when we landed,” Hill said.

Captain Inglis felt a mounting frustration. “We tried our

best to determine the source of this fire, but the Japanese, being past masters

in the twin arts of playing possum and camouflage, had very successfully

concealed their batteries from observation and the source of the fire could not

be determined from observation from the ship, or from the spotters ashore, nor

from observation from aircraft, nor from photographs taken by aircraft.” There

were many eyes on D Day, but none were all-seeing. It remained to the

assaulters to push forward and deliver themselves from death.

The Second Armored Amphibian Battalion, a Marine outfit, hit

Red Beach One promptly at H Hour. General Watson, who hadn’t wanted to use his

regular amtracs as fighting vehicles on land, had his men debark from the

troop-carrying LVTs immediately, to begin the fight in the footprint of the

tides. As LVTs unloaded elements of the Second Battalion, Sixth Marines, high

on the beach, the unit’s seventeen LVT(A)-4 amtanks sought routes inland, to

serve as a sort of mobile amphibious armored striking force. Their crews were

freelancers as soon as they went ashore, and thus they acquired a fearsome

responsibility: to use their thin-skinned “armored pigs” to hold the exposed

far left flank of the entire two-division landing beach. This meant facing off

against anything the Japanese might send them from the north. Turner had

anticipated this; the whole purpose of the feint he had carried out off Garapan

was to let the first two battalions of the Sixth Marine Regiment get ashore and

dig in before a counterattack came.

“I never will forget the concussion of the battleships’ guns

and the power and compression that blew over us,” remembered R. J. Lee. The

driver of his amtank was looking to push inland off the beach, but with a deep

trench just behind the shrub line there was no way forward. He threw the pig

into reverse and backed out to the water’s edge, where he unlimbered the 75 mm

cannon and began blasting to cut a navigable lane. The Japanese had built only

the simplest of defensive works, thanks to the efforts of U.S. submarines to

strangle their source of supply. But their trenches, foxholes, and log obstacles

near the beach were made reasonably effective by the pressure of artillery and

mortar fire coming from the highlands far away. Marine amtanks on Red Beach

struggled to get over the bluffs behind the beaches. Lee had gotten off perhaps

four shots when Japanese artillery found his range. The open turret took a

direct hit. Before the smoke washed everything black, Lee saw his platoon

leader and two of his sergeants dead.

“Let’s get the hell out of here before she blows up,”

another sergeant said to the five survivors. The amtank’s seven-cylinder radial

aircraft engine, owing to the aviation gasoline that fed it, was always a fire

hazard. They shimmied through the escape hatch into the water and turned and

charged the beach, weapons held high. Lee looked to his right and saw one of

his crew, Gus Evans, rifle raised over his head, take a bullet to the face and

go down. He was reaching for him when he, too, was hit. Two head shots—one a

ricochet, the other penetrating the helmet but somehow retaining only enough

force to knock him cold. “Lights out for me,” Lee said. “I heard my

four-year-old son calling, ‘Get up, Daddy, get up, Daddy,’ and by the grace of

God and my son I made it back to the beach.”

On Red Three, a trio of amtanks under the command of

Lieutenant Philo Pease found a path through a grove of trees and made it up

onto the bluff. Crossing a narrow road, they approached a trenchworks. The lead

vehicle tried to cross it but came to grief, stuck fast, treads clawing the

air. According to the driver, S. A. Balsano, Japanese soldiers were “on us like

flies.” There was no way forward, or back, either, for the rear amtank was

stuck, too. Lieutenant Pease realized their only hope was to get moving again,

or artillery would surely find them. He saw that the second amtank in his

column, the one right behind him, might be able to pull the third one free of

its snag. He ordered his crew to stay with their stranded lead vehicle and try

to break it free while he ran outside, exposing himself in order to help the commander

behind him to rig a tow cable. As a cluster of enemy troops approached, one of

Pease’s crew, Leroy Clobes, stuck a light machine gun through the side hatch

and leaned into the trigger, scattering them. Balsano, the driver, jammed his

Thompson through the front hatch and jackhammered away. Then they realized that

the foreign voices they had heard were coming from the trench beneath them.

Pease reached the amtank behind him only to find himself

going to the assistance of a dead man. A Japanese soldier had drawn a bead on

the other commander and shot him dead where he stood. Ducking low under fire,

Pease inherited the job of attaching the cable. The enemy rifleman chambered

another round and took him down next. A corporal in Pease’s amtank, Paul

Durand, took command, shouting, “Shoot all the sons of bitches you can!” Nearby

he spotted a straw house that seemed to harbor an enemy squad. Traversing the

75 mm gun onto it, he blew it right down. At that point a Japanese light tank

appeared and put a 37 mm round through the hull of the third amtank in line,

killing the driver. Marine bazookamen put the enemy armored vehicle out of

business in turn, but here, exposed under merciless direct fire, was the root

of General Watson’s worry all along: Amtracs were sitting ducks. Lieutenant

Pease’s surviving crew were lucky. Inspecting their stranded amphibian later,

one of them found a magnetic mine fastened to the undercarriage. Somehow it had

failed to explode.

South of them, Green Beach One was chaos, its six-hundred-yard

frontage hopelessly congested after the arrival of two full battalions. The

commanders of the first wave’s amtanks tried to deepen the beachhead by driving

inland. Their advance was conspicuous to the well-spotted mortarmen and

artillery gunners in the hills. Coming under heavy plunging fire, several of

the amtanks became bogged down in a rice paddy. Two others, driven by Sergeant

Benjamin R. Livesey and Sergeant Onel W. Dickens, pushed on. Crossing the end

of the single runway paralleling Green Beach, they turned up a dirt road

leading north past the Japanese radio station. The road was little more than a

cart path, barely wide enough for two-way traffic. Along it they clattered,

fortunate to evade the incoming fire. A Japanese machine gun nest, then another,

revealed themselves with spitting tracers. The armored amphibians turned the

fury of their 75 mm howitzers and .50- and .30-caliber machine guns onto them,

to overwhelming effect. Passing through a banana grove, Livesey realized its

value as cover and stopped there as the mortars continued to fall. As the crew

crouched low, they heard the chatter of small arms fire as Japanese soldiers

opened up on them from down the road. “We scrambled back into our tank,”

Livesey said, “and scanned ahead into the grove of trees, using our gun sight

and binoculars to spot a building with some Japs moving around inside it. We

opened fire with everything we had.”

Their 75 mm main gun was loaded with high-explosive and

incendiary rounds. Several hits produced larger explosions followed climactic ally

by a mushrooming fireball that marked the demise of a Japanese fuel dump.

Livesey ordered his driver forward and shot up the area for effect. About a

hundred yards on, he came upon a clearing and stopped again, breaking out water

for his crew. As Dickens’s amtank rolled up alongside, Livesey and his men

dismounted to talk with them. No other Marines had yet made it that far inland.

“We were alone and isolated,” Livesey said, “but enjoying our success.” They

were picking through the wooden crates that constituted their magazines,

counting their remaining shells, when, down the road, four behemoths of foreign

origin loomed into view.

The Japanese medium tanks were in a single column, moving

toward the landing beach. They did not seem to see the Americans hustling to

remount. Once buttoned in, Livesey and Dickens turned out after them,

unlimbering their 75 mm guns and opening fire. His ammunition passers were

scrambling to find armor-piercing shells when the enemy column turned and came

directly at the Marines. “It was us or them,” Livesey said.

Neither side’s vehicle was a match for the other’s main gun.

Livesey’s vehicle shook from a hit to its engine compartment, but June 15 was

his day; the shell was a dud. Gales of machine gun fire washed over them.

Though the 75s liked to jam and did, the gunners and loaders kept their breech

blocks smoking, and Marine Corps marksmanship was equal to the moment.

Destroying three of the enemy tanks in succession, they stopped the Japanese

armor just fifty to seventy yards away. Livesey watched one of the enemy

tankers pile out of his hatch and start running for the hills, a good thing

given that Livesey’s ammunition passers were nearly down to smoke shells. He

threw a few rounds after the enemy squirter, but as artillery and mortars in

the hills began bracketing them again, he and Dickens and their crews opted to

bail out. As they set out on foot to the beach, mortar shrapnel killed one of

Dickens’s men, Private Leo Pletcher. The freelancing foray by Livesey and

Dickens would earn each of them a Navy Cross. More important, it relieved

pressure on the vulnerable Second Marine Division foothold by blunting an

armored assault that might have fallen upon the beach.

The fighting on the left flank continued stiff and sharp.

The Sixth Marines were able to force a shallow beachhead no more than a hundred

yards deep, as far as the coastal road behind Red Beach. But pillboxes and

machine gun positions checked their progress. An enemy tank on the beach that everyone

had thought was disabled opened fire with its 37 mm gun on the LVTs that were

bringing in the Sixth Marines’ reserve unit, the First Battalion, under

Lieutenant Colonel William K. Jones. One of the vehicles that got hit was

carrying the staff of Jones’s boss, the regimental commander, Colonel James P.

Riseley. Many of them were badly wounded. Soon after landing, Riseley learned

that the commander of his Third Battalion, Lieutenant Colonel John W. Easley,

had been hit, too.

As Riseley was setting up his regimental command post near

the center of Red Beach Two, as many as two dozen Japanese troops charged down

the beach from the north. They reached the rear area of the regiment’s Second

Battalion, where wounded Americans were laid out in stretchers under tents near

the beach. The Marines rallied, established a firing line, and annihilated the

Japanese force. But the close-run assault proved that no one was safe in a

battle of infiltration. On the day, the commanders of all four of the Second

Marine Division’s assault battalions were wounded in action: Raymond L. Murray

of the 2/6 (hit along with his executive officer), Henry P. Crowe of the 2/8,

John C. Miller of the 3/8, and Easley of the 3/6. After nightfall, the task of

closing the gaps in their lines would be a matter of life and death.

To break the pressure of the counterattack, Riseley ordered

the First Battalion to pass through the Third Battalion area and renew the push

toward the O-1 line. Riseley would have given the job to no one other than the

1/6’s commander, Lieutenant Colonel Jones. He would call him “the best damn

battalion commander in this division, or any other division.” At the moment,

Jones was the only officer of his rank physically able to lead an assault on

that high ground. The 1/6 had taken a hundred casualties on the way to the

beach. Coming ashore, the survivors had replaced their soaked equipment and

gear by harvesting from those who had fallen ahead of them. Jones rallied them

forward.

With units scattered and intermingled thanks to the

whirligig movements of amtracs in surf and tide, and with the heavy fire urging

survival ahead of record keeping, it was difficult to count the wounded. The

first casualties were brought to the beach for loading onto LVTs at about

10:40. The total number of killed and wounded that day would total more than

two thousand, most of the casualties inflicted by artillery and mortar fire.

But an untold multitude emblematized by Lieutenant Colonel Easley refused to

report to triage for fear of being removed from the company of their men at the

front.