The Battle of Manzikert was fought between the

Byzantine Empire and the Seljuq Turks on August 26, 1071 near Manzikert (modern

Malazgirt in Muş Province, Turkey). The decisive defeat of the Byzantine army

and the capture of the Emperor Romanos IV Diogenes played an important role in

undermining Byzantine authority in Anatolia and Armenia, and allowed for the

gradual Turkification of Anatolia.

Alexius I Comnenus in Eastern Greece Then he was

surrounded by nine Normans who stuck him with spears. But his heavy cataphract

armor stopped all six spears and his horse bolted and he managed to escape.

In Mecca, eight hundred miles south of Jerusalem, in a

landscape as bleak and parched as the Judaean wilderness, there existed another

empty tomb. This was the kaaba, or “cube,” where according to Islamic tradition

Ishmael and his mother, Hagar, Abraham’s Egyptian concubine, were buried.

Originally built by Abraham, it was later used as a temple for the worship of

Hubal, the red-faced god of power, and al-Uzza, the goddess of the morning

star, together with three hundred other gods and goddesses who formed the

pantheon of the Arabs before Muhammad destroyed them. Then the kaaba was

dedicated to Allah, the One God, lord of all universes. There was nothing in it

except silver lamps, brooms for sweeping the floor, and the three teakwood

columns that supported the roof. Fragments of a black meteorite were inserted

in the southeastern wall, and these are kissed by the faithful who walk, and

run, around the kaaba in obedience to Muhammad’s command.

The kaaba is a statement of religious belief—four-square,

sharp-edged, emblematic of the power believed to reside in the Arab people.

Those qualities were already present in these people before the coming of

Muhammad. It was their sharpness of intellect and solidness of purpose that

were to make them a world power, and Muhammad was therefore justified in

retaining that strange unornamented box, which had once housed so many gods, as

the symbol of his own powerful faith in Allah, the One God.

The faith of Muhammad was unlike any other that existed at

that time. It was compounded out of visions and dreams, the apocrypha learned

along the camel routes from Mecca to Damascus, stray bits of learning and

tradition, and a vast understanding of the human need for peace and salvation.

The Koran, meaning “the Recitations,” reads strangely to Western ears. It is a

work of fierce intensity and trembling urgency. God speaks, and what he has to

say is recorded in tones of absolute authority by a mind singularly equipped to

reflect the utmost subtleties of the Arabic language. The message Muhammad

delivers is that God is all-powerful, his hand is everywhere, and there is no

escape from him. Just as he is everywhere, so is his mercy. Into this mercy

fall all men’s accidents and purposes. It is not that God is benevolent–the

idea of a benevolent and helping God is foreign to Muhammad’s vision–but his

mercy is inevitable, uncompromising, absolute. In this assurance Muhammad’s

followers find their peace.

Muhammad ibn-Abdullah, of the tribe of Quraysh, was born in

Mecca about the year A.D. 570. His father died before he was born and his

mother, Amina, died when he was a child. As a youth he traveled with the

caravans that traded between Mecca and Syria, and he was twenty-five when he

married Khadija, a rich widow fifteen years his senior. He was about forty when

he first saw visions and heard the voice of the Angel. Out of these visions and

voices came the revelations he attributed directly to God.

According to Islamic tradition, Muhammad commanded that the

human figure must never be depicted, so he himself is very rarely depicted in

Islamic art. On the rare occasions when he is seen, he wears a veil over his

face. But his friends remembered him and described him. They spoke of a

thickset man with burly shoulders, a rosy skin “like a woman’s,” a thick,

black, curling beard. Most of all they remembered his eyes, which were very

large, dark, and melting. The clue to his personality lies perhaps in his rosy

skin, for he was no sun-bitten Bedouin of the desert, but a townsman with a

townsman’s peculiar sensibilities and perplexities.

In a cave on Mount Hira, not far from Mecca, he would spend

time meditating. There he became aware one day of the presence of the Angel

standing “two bow shots away,” watching him. “O Muhammad, you are God’s

messenger and I am Gabriel,” the voice thundered. From the Angel he learned

that man was created from a clot of blood and lay under the protection of

Allah, the Only God, the All-Merciful, whose mysteries would be revealed to

him. Thereafter, day after day, in waking visions, Muhammad was visited by the

Angel who expounded mysteries testifying to God’s mercy and absolute power in

verses that crackle and roar like a brushfire.

Half-learned in the religions of his time, impatient with

all of them, Muhammad struck out into unexplored territories with a new style,

a new rhythm, speaking urgently in a voice of great power:

That which striketh!

What is that which striketh?

Ah, who will convey to thee what the Striking is?

The day mankind shall become like scattered moths,

And the mountains like tufts of carded wool.

Then those whose scales weigh heavy shall enter Paradise,

And those whose scales are light shall enter the Abyss.

And who shall convey to thee what the Abyss is?

A raging fire!

(Sura ci)

Like Jesus, Muhammad was haunted by the Last Day. The end

seemed very near, but instead of simply submitting to the dissolution of the

universe, there must be in this waiting time a change of heart, a total

submission to God. Muhammad felt that the laws of submission must be

discovered, and that men should find the way in which to hold themselves in the

light of the coming flames. In these visions, dictated over a long period,

Muhammad presented a cosmology of breathtaking simplicity, rounded, complete,

and eminently satisfying to the Arab mind.

His torrent of visionary poetry convinced Muhammad’s friends

that he was indeed a prophet and a messenger of God. Soon he acquired followers

and an army. Medina fell, and then Mecca, but these were only the beginnings.

The furious pent-up poetry, so memorable and so naked, had the effect of

inspiring the Arabs to challenge all their neighbors on behalf of the messenger

of God. The Jews must be converted; so must the Christians; all the world must

acknowledge the truth of the Koran. Muhammad also proved to be a gifted

military commander. His successors were even more gifted. They came like

thunder out of Arabia. Within a generation after Muhammad’s death in A.D. 632,

long-established empires fell like ninepins, and half the known world, from

Spain to Persia, fell to the armies he had set in motion.

Out of the blaze of Muhammad’s visionary eyes there came a

force that shook the world to its foundations.

In July A.D. 640, eight years after Muhammad’s death, an

Arab army under Amr ibn-al-As stood outside the walls of the great university

city of On, the modern Heliopolis, where the Phoenix was born and where Plato

had once studied. On was the most sacred of Egyptian cities, and one of the

oldest. Egypt was then a province of the Byzantine empire, and the viceroy was

Cyrus, Patriarch of Alexandria. The Arabs attacked, Cyrus fled to the north,

and soon the Arabs pursued him to Alexandria, where there were huge battlements

and siege works and a harbor that included within its ample seawalls the

largest naval base in the world. For a thousand years the Greeks and the Romans

had been quietly building a city so powerful and so sumptuous that no other

city could rival it. Gleaming between the sea and a lake, illuminated by the

great lighthouse called the Pharos in the harbor, with powerful ships riding at

anchor, and guarded by an army believed to be the best in the world. Alexandria

was a bastion of Byzantine power in Africa. The scholarly and ambitious Cyrus

looked upon the guerrilla army lodged outside the walls of Alexandria with

cunning and distaste. He thought he could bargain with Amr ibn-al-As, while the

citizens continued to receive supplies by sea, to attend the racetrack and to

worship in the great cathedral of St. Mark overlooking the two harbors. Cyrus

was overconfident.

In time, Alexandria fell and the Arabs rode in triumph

through the Gate of the Sun and along the Canopic Way, past Alexander the

Great’s crystal tomb. What they did to Alexandria is described very aptly by E.

M. Forster: “Though they had no intention of destroying her, they destroyed

her, as a child might a watch.”

The Arab army also raged through Palestine and Syria, swung

eastward toward Persia, and defeated the army of the Sassanian emperor in the

same year that Cyrus surrendered Alexandria. Two years later the Arabs were in

command of all of Persia. The Umayyad dynasty, ruling from Damascus, derived

from the Persians the habits of splendor. Luxury and corruption set in: the grandsons

of the followers of Muhammad preferred to be city dwellers. The same corruption

soon became evident in North Africa and Spain, which the Arabs conquered with

incredible speed. In A.D. 732, a hundred years after the death of Muhammad, the

Arabs poured into France, where they were defeated by the ragged army of

Charles of Heristal and the bitterly cold weather.

The Arab tide was turned back, but the Arab empire now

extended halfway across the known world from the Pyrenees to Persia. It had

made inroads into India, and Arab armies were breaking through the Asiatic

outposts of the Byzantine empire, which would endure for another seven hundred

years. The Muslims regarded Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine

empire, as the eastern gateway to Europe: it must be captured and all Europe

must fall under their sway.

The Christians saw in the religion of Muhammad a mortal

enemy to be opposed at all costs. The name of the religion was Islam, which

means “submission,” “submission to God’s purposes.” The Christians were not

prepared to submit. They regarded Islam as a heresy, a diabolic and dangerous

perversion of the truths handed down by Moses, the prophets, Jesus and St.

Paul. Islam was monotheism stripped bare, unclouded by ambiguities, without

mysteries, without vestments, without panoply, without hierarchies of priests,

democratic in its organization, abrupt and simple in its protestations of

faith. There are no complex ceremonies in Islam, no Nicene Creed, no Mass, no

tinkling of bells. A mosque is usually a walled space open to the sky with a

pulpit, a prayer niche, and a tower from which the faithful are called to

prayer; the religion, too, is open, spacious, clear-cut, without shadows. God

is conceived as an abstraction of infinite power and infinite glory, the source

and end of all things. That God should in some mysterious way be divided into

the Father, the Son and the Holy Ghost was incomprehensible to the Muslims, who

conceived of him as one and indivisible.

Although Islam reserved a special place for Jesus, the

Islamic Jesus is almost unrecognizable to Christians. Muhammad tells the story

of the Virgin Birth three times and is deeply moved by it, and he is aware of

something supernatural in Jesus, but he has no patience with those who proclaim

his divinity. Jesus is a sign, a word, a spirit, an angel; he is also a

messenger and a prophet. He could raise the dead, heal the sick, and breathe

life into clay birds. He was not crucified in the flesh, for someone else was

crucified in his stead. He ascended to heaven when God summoned him, and he

will return in the Last Day.

No one knows where Muhammad learned about Jesus. Most likely

it was from some lost Gnostic scriptures, or he may have listened to a

Christian preacher during his travels. Mary and Jesus “abide in a high place

full of quiet and watered with springs”; and there, very largely, they remain.

They are peripheral to his main argument, which is concerned with the nature of

man, the clot of blood, confronted with the stupendous presence of God, who is

both far away and as close to man as his neck artery. Man is naked and

defenseless; he has nothing to give God except his utter and total devotion.

God, to the Muslims, has no history, while to the Christians the history of God

is bound up with the history of Christ.

The two religions had no common ground, or so little that it

could scarcely be perceived. It was as though Christianity and Islam were meant

to engage in a death struggle, which would end only when one submitted to the

other. Yet there were long periods when there was a kind of peace between them.

Jerusalem, captured very early by the Arabs, was permitted to retain a

Christian community, and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre remained untouched.

Charlemagne conducted a long correspondence with Harun al-Rashid, Caliph of

Baghdad, who acknowledged the right of the Christians to maintain their church.

Harun gave the church over to Charlemagne, who was addressed as “Protector of

Jerusalem.” Although Charlemagne never visited Jerusalem, he sent a stream of

envoys, founded a hospital and library in the Holy City, and paid for their

upkeep. Throughout the ninth century, relations between Christians and Muslims

were fairly amicable. The Christians demanded only that Jerusalem should be

accessible to them, and that pilgrims to the Church of the Holy Sepulchre

should be treated reasonably. And so it continued for another century. Even

after the destruction of the church by the mad Caliph Hakim, there was peace,

for the church was quickly restored. The pilgrims continued to come to

Jerusalem, worshipping at the altars in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre,

passing freely in and out of the city. It was as though the two religions had

reached an accommodation, as though nothing would interrupt the continual flow

of pilgrims.

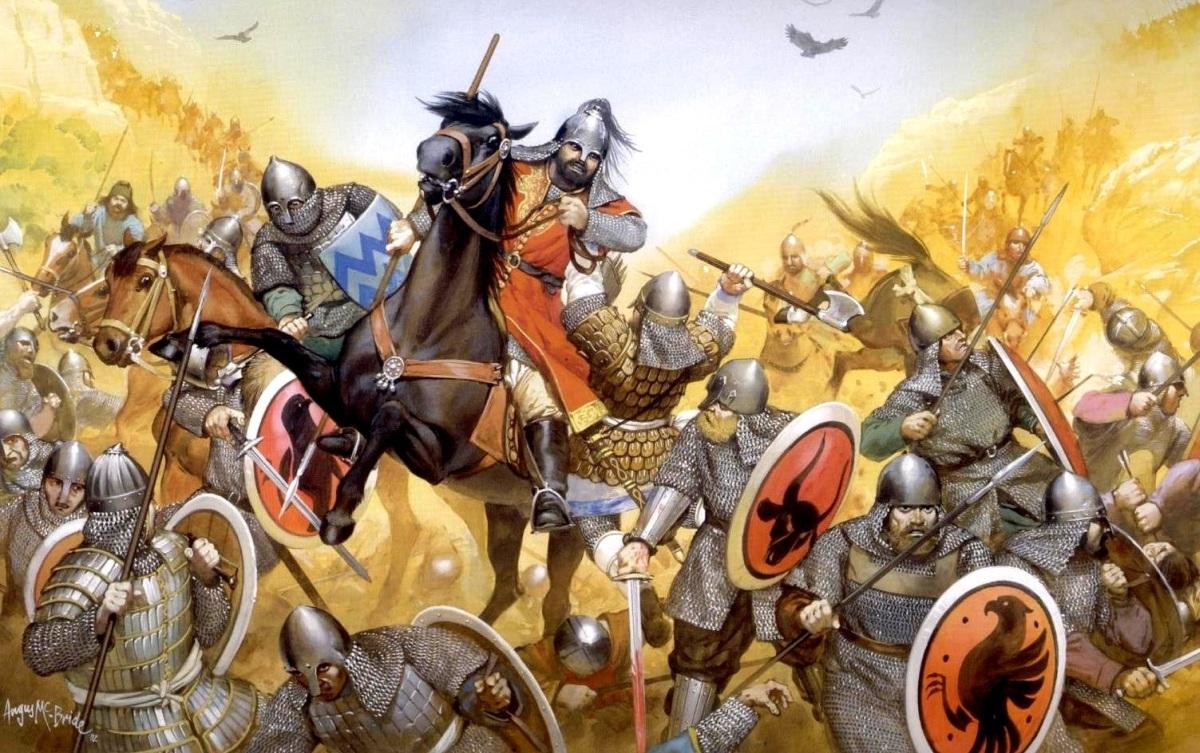

In the middle years of the eleventh century there occurred

an event that would cause a drastic change in the military posture of the

Muslims in the Near East. The Seljuk Turks, advancing from Central Asia,

conquered Persia. Converted to Islam, they moved with the zeal of converts,

prosetyliz-ingall the tribes they came upon in their lust for conquest. They

had been herdsmen; they became raiders, cavalrymen, living off the earth,

setting up their tents wherever they pleased, taking pleasure in sacking cities

and leaving only ashes. The once all-powerful Caliph of Baghdad became the

servant of the Seljuk Sultan Alp Arslan. In August 1071, the Seljuk army under

Alp Arslan confronted the much larger army of the Byzantine Emperor Romanus IV

Diogenes near Manzikert north of Lake Van in Armenia. Romanus was an emperor

with vast military experience, brave to excess, commanding a hundred thousand

well-trained troops, including many Frankish and German mercenaries. There was,

however, treachery among his officers; orders were not obeyed. The lightly

armed Seljuk cavalry poured thousands of arrows into the tight formations of

the Byzantine army, and when the emperor ordered a retreat at the end of the

day, his flanks were exposed, his army began to disintegrate, and the Turks

rushed in to fill the vacuum created by his retreating troops. Romanus fought

bravely; he was seriously wounded in the arm and his horse was killed under

him. Captured, he was led to the tent of Alp Arslan in chains. There he was thrown

to the ground, and Alp Arslan placed his foot ceremonially on the emperor’s

neck. The Seljuk sultan half-admired the broad-shouldered Byzantine emperor,

and two weeks later the emperor was allowed to go free. Still the defeat was so

decisive, so shattering, that the emperor fell from grace in the eyes of the

Byzantines, who had no difficulty deposing him. When he returned to

Constantinople, he was blinded, and in the following year he died either from

the injuries caused by the blinding or of a broken heart.

Although Alp Arslan himself, and his son Malek Shah, had no

thought of conquering the Byzantine empire, the chieftains who served under

them had different ideas. They poured into the undefended provinces of

Anatolia. While the Christians remained in the towns, the invading Turks

ravaged the countryside. Gone were the days when the Byzantine empire stretched

from Egypt to the Danube and from the borders of Persia to southern Italy. The

Turks advanced to Nicaea, less than a hundred miles from Constantinople, and

occupied the city, making it the capital of the sultanate that ruled over Asia

Minor. The Turks were spreading out in all directions. In the same year that

saw the Byzantine defeat at Manzikert, they captured Jerusalem from the Arabs

of Egypt on behalf of the Caliph of Baghdad. In 1085 Malek Shah captured

Antioch from the Byzantines. Malek Shah himself came to the Palestinian shore

and dipped his sword in the waters of the Mediterranean, a ceremony by which he

asserted that the Mediterranean itself belonged to him.

The grandson of nomads from Central Asia, Malek Shah had the

temperament of an emperor. He was more relentless, more determined, than his

more famous father. He ruled in great state and saw himself as the sovereign of

all the Near East. His Turks were rougher than the Egyptians; they had come

like thunder from the regions north of the Caspian and they possessed to the

highest degree what the historian Ibn Khaldun called assabiya, the

determination based on a communion of interests that characterized the early

Arab conquerors. The Arabs had made accommodations with the Christians; the

Turks were more sure of themselves.

Christendom was reeling from the Turkish invasions. In a

single generation Asia Minor had fallen into their hands. The Byzantine empire

had lost the sources of its greatest wealth. Christians could no longer be

assured that they could journey to Jerusalem without being arrested or sold

into slavery or ill-treated in other ways. The Turks were fanatical Muslims,

determined to exact the last ounce of power from their victories. But their

survival as a united people depended on their leader, and when Malek Shah died

in 1091, the empire was divided up among his sons and nephews, whose hatred for

one another contributed to the early success of the Crusaders when at last they

made their way across Asia Minor in order to recover Jerusalem.

In 1081, Alexius Comnenus, who had served in the army of

Romanus IV Diogenes as a general fighting against the inroads of the Turks,

came to the throne at the age of thirty-three. He was an able commander in the

field and uncompromising in his determination to regain the lost provinces of

his empire. His daughter, Anna Comnena, wrote a history of his reign that is

among the acknowledged masterpieces of Byzantine literature. Through her eyes

he appears as a superb diplomat, a man who moved surefootedly amid treacheries,

who knew his own value and was both forceful and humble in dealing with his

friends and enemies. He reigned for thirty-seven years, recaptured some of the

lost provinces, and there were few Byzantine emperors who reigned so long or

fought so well.

When Alexius Comnenus came to the throne, the empire was in

disarray. Although the Balkan provinces had been recaptured from Robert

Guiscard, the Norman-Sicilian adventurer who founded his own kingdom in southern

Italy and Sicily, he was confronted with dangers along the long Danube border

from the Oghuz, Kuman, and Pecheneg Turks, half-brothers to the Turks in Asia

Minor, and from Slavs and Bulgars. Only a few coastal cities in Asia Minor

remained in his hands. It was necessary at all costs to push back the frontiers

of the sultanate of Roum. He appealed for military assistance to the pope and

to the Western princes who might be sympathetic to his cause. They were asked

to raise armies, to march to Constantinople and to join forces under the banner

of Christendom against the infidels. He recounted the atrocities committed by

the enemy and pointed to the peculiar sanctity of Constantinople as the guardian

of so many relics of Christ. Constantinople and the Byzantine empire must be

saved, Jerusalem must be reconquered, and the pax Christiana must be

established in the Near East. A copy of his letter to Robert, Count of

Flanders, a cousin of William the Conqueror, has been preserved. The emperor

speaks with mingled anguish and pride, despair and humility, and from time to

time there appears a faint note of humor.

EXCERPTS FROM A LETTER FROM THE EMPEROR ALEXIUS COMNENUS TO

ROBERT, COUNT OF FLANDERS, WRITTEN FROM CONSTANTINOPLE IN A.D. 1093.

TO THE LORD AND GLORIOUS COUNT, Robert of Flanders, and

to the generality of princes of the kingdom, whether lay or ecclesiastical,

from Alexius Comnenus, Emperor of Byzantium.

O illustrious count and great consoler of the faith, I am

writing in order to inform Your Prudence that the very saintly empire of Greek

Christians is daily being persecuted by the Pechenegs and the

Turks. . . . The blood of Christians flows in unheard-of

scenes of carnage, amidst the most shameful

insults. . . . I shall merely describe a very few of

them. . . .

The enemy has the habit of circumcising young Christians

and Christian babies above the baptismal font. In derision of Christ they let

the blood flow into the font. Then they are forced to urinate in the

font. . . . Those who refuse to do so are tortured and put

to death. They carry off noble matrons and their daughters and abuse them like

animals. . . .

Then, too, the Turks shamelessly commit the sin of sodomy

on our men of all ages and all ranks . . . and, O misery,

something that has never been seen or heard before, on

bishops. . . .

Furthermore they have destroyed or fouled the holy places

in all manner of ways, and they threaten to do worse. Who does not groan? Who

is not filled with compassion? Who does not reel back with horror? Who does not

offer his prayers to heaven? For almost the entire land has been invaded by the

enemy from Jerusalem to Greece . . . right up to Thrace.

Already there is almost nothing left for them to conquer except Constantinople,

which they threaten to conquer any day now, unless God and the Christians of

the Latin rite come quickly to our aid. They have also invaded the

Propontis . . . passing below the walls of Constantinople

with a fleet of two hundred ships . . . stolen from us.

They forced the rowers against their will to follow the sea-roads chosen by

them, and with threats and menaces, as we have said, they hoped to take

possession of Constantinople either by land or by sea.

Therefore in the name of God and because of the true

piety of the generality of Greek Christians, we implore you to bring to this

city all the faithful soldiers of Christ . . . to bring me

aid and to bring aid to the Greek Christians. . . . Before

Constantinople falls into their power, you should do everything you can to be

worthy of receiving heaven’s benediction, an ineffable and glorious reward for

your aid. It would be better that Constantinople falls into your hands than

into the hands of the pagans. This city possesses the most holy relics of the

Saviour [including] . . . part of the True Cross on which

he was crucified. . . .

And if it should happen that these holy relics should

offer no temptation to the pagans, and if they wanted only gold, then they

would find in this city more gold than exists in all the rest of the world. The

churches of Constantinople are loaded with a vast treasure of gold and silver,

gems and precious stones, mantles and cloths of silk, sufficient to decorate

all the churches of the world. . . . And then, too, there

are the treasuries in the possession of our noblemen, not to speak of the

treasure belonging to the merchants who are not noblemen. And what of the

treasure belonging to the emperors, our predecessors? No words can describe

this wealth of treasure, for it includes not only the treasuries of the

emperors but also those of the ancient Roman emperors brought here and

concealed in the palace. What more can I say? What can be seen by human eyes is

nothing in comparison with the treasure that remains concealed.

Come, then, with all your people and give battle with all

your strength, so that all this treasure shall not fall into the hands of the

Turks and Pechenegs. . . . Therefore act while there is

still time lest the kingdom of the Christians shall vanish from your sight and,

what is more important, the Holy Sepulchre shall vanish. And in your coming you

will find your reward in heaven, and if you do not come, God will condemn you.

If all this glory is not sufficient for you, remember

that you will find all those treasures and also the most beautiful women of the

Orient. The incomparable beauty of Greek women would seem to be a sufficient

reason to attract the armies of the Franks to the plains of Thrace.

In this way, mingling allurements and enticements with

intimations of the final disaster that would overwhelm the community of

Christians if the Turks and Pechenegs succeeded in conquering what was left of

the Byzantine empire, Alexius Comnenus appealed to Robert of Flanders to come

to his aid. The letter contained admissions of terrible defeats and was

sustained by a vast pride, but it also provided a picture of the world as he

saw it, with its pressing dangers and wildest hopes. Two images prevailed: the

atrocities committed by the enemy, and the spiritual and material wealth of

Constantinople, last bastion against the Turks.

The letter was addressed not only to Robert of Flanders but

to Western Christendom. Pope Urban II read it and was deeply moved. Robert of

Flanders would eventually take part in the Crusade. And now very slowly and

with immense difficulty there came into existence the machinery that would

bring the armies of the West to Constantinople and later to Jerusalem.