The frontal view shows the flying bridge, the elevated

forward control and navigation house, the sponsons, and the rounded hull shape.

From this deck plan the redoubt’s diagonal arrangement

is clear. There was an armoured deck just below waterline level, but no citadel

or side armour.

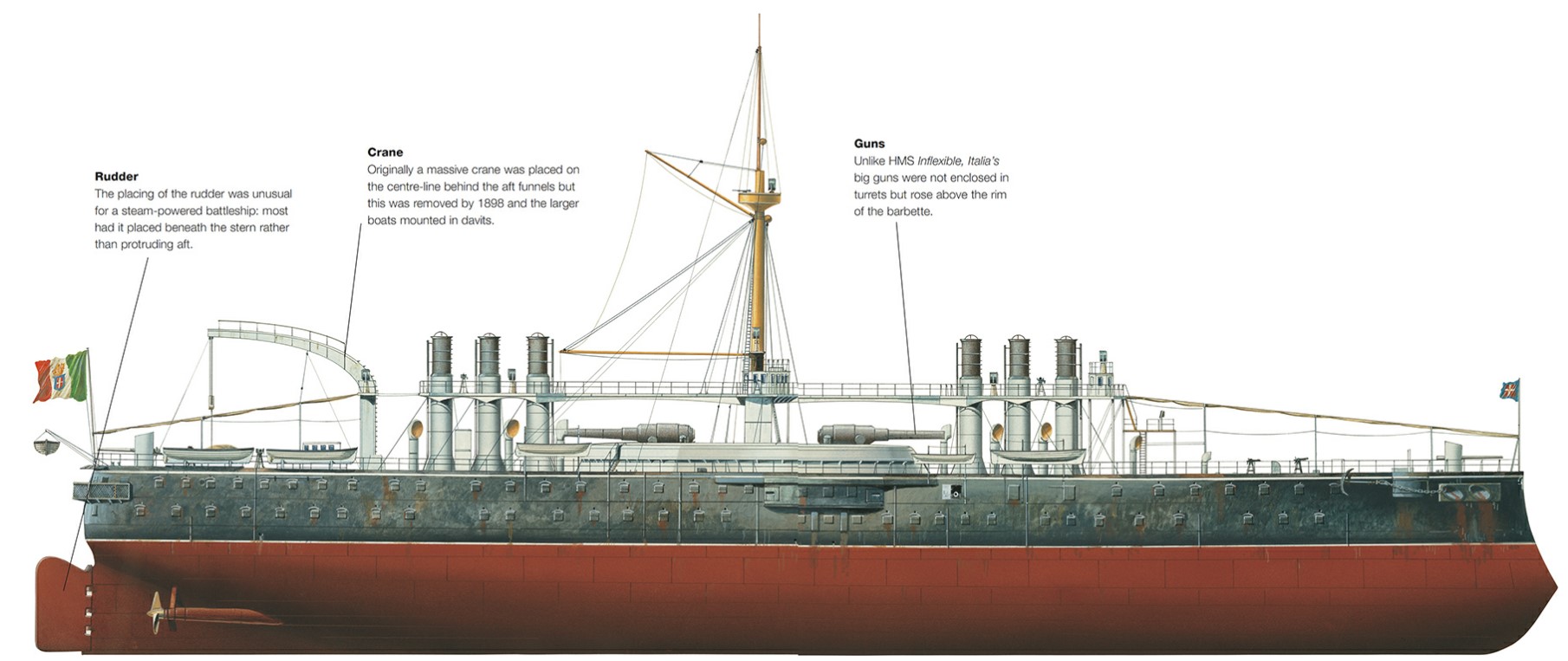

A novel battleship design, with four very large guns and no

side armour, in many ways Italia was a forerunner of the battlecruiser. For a

few years it held the prestige position of the largest and fastest battleship

in the world.

The Kingdom of Italy was declared in 1861 and from the start

it had difficult relations with the French and the Austrians. For Italy with

its long coasts and numerous islands, a naval force was a prime necessity, and

by 1866 it had fought one of the first ‘modern’ sea battles, against the

Austrian Navy at Lissa in the Adriatic Sea. That was a defeat despite superior

numbers on the Italian side, and drove the Italians to further expansion of

their fleet.

Fast and powerful

Laid down at Castellamare in 1877 and launched in 1880,

Italia took Brin’s revolutionary design of Duilio (1876) to an extreme. The

brief was for a very fast ship, heavily-armed, which could also carry a large

number of troops (at the time, France and Italy were on the verge of war over

Tunis, on the south coast of the Mediterranean Sea). As with Duilio, the guns

were mounted in echelon, but the main armament of Italia and its sister ship

Lepanto was of even heavier calibre, four 432mm (17in) guns each weighing 93

tonnes (103 tons), firing shells of 907kg (2000lb). The guns were mounted in a

huge barbette of oval shape extending beyond the sides, forming an armoured

redoubt set diagonally across the hull. Unlike the British Inflexible, it had a

high freeboard, 7.6m (25ft), offering more of a target to an enemy. The sides

carried no armour, but Italia relied on the power of its guns, and its high

speed, to avoid attack. Six funnels in sets of three, linked by high catwalks

with the conning tower, a lofty central mast, and a large curved crane on the

afterdeck, gave Italia a unique appearance. One of the few more traditional

features was an ‘admiral’s walk’ around the curved stern.

Fittings

The ship was built largely of steel, rather than iron.

Internally it had the now-standard armoured deck, curving upwards slightly from

the sides 1.83m (6ft) below the waterline, but above it a cellular raft ran the

entire length of the ship. The space between them was lined laterally with

cork-filled watertight cells separating the hull plating from an inner cofferdam

on each side, and two transverse levels, one of empty cells, with coal storage space

below. A double bottom was also fitted.

One novel feature of Duilio, not maintained on the new ship,

was a stern compartment for a torpedo boat, secured by watertight doors. Italia

also had space to hold an infantry division of 10,000 men and its equipment for

the relatively short Mediterranean crossing. The main guns could be

independently trained and aimed, but as with other very large guns of the time,

the rate of fire was slow, no more than one round every four or five minutes.

Construction of Italia and Lepanto stretched Italy’s new

warship-building resources, and the Italian government did not proceed to

enlarge its battlefleet further. But the size, speed and general innovation of

these Italian capital ships had a major impact on ship design and naval

planning in both the British and the French navies. Sir Nathaniel Barnaby,

Britain’s chief naval designer, observed that ‘We must … regard the first-class

ironclad as … being of over 14,000 tons if we accept the reasonings of the

Italian architects and the expression of their ideas in the Italia and

Lepanto’. In the mid-1880s British designers were still mulling over the kind

of ship ‘most suitable for meeting the Italia’. In this way the Italian

contribution was to push the greater naval powers towards greater size.

Rebuild

Between 1905 and 1908 Italia was rebuilt, losing two funnels

and with the tall single mast replaced by two, forward and aft of the funnels.

By this time battleship development had caught up and moved on. Improved armour

had disproved Brin’s theory that gun-power had made side-armour pointless, and

the formidable guns were sadly out of date. By the 1890s the ship really ranked

with armoured cruisers. The secondary armament was changed and reduced in

quantity. In 1909–10 it was used for torpedo training.

Still in commission during World War I, but renamed as

Stella d’Italia, it was based at Taranto and Brindisi for gunnery training

until 1917, when it was disarmed and transferred to the mercantile marine as a

grain transport. It was returned to the Regia Marina in 1921, but was almost

immediately sold for scrapping.

Specification

Dimensions

Length 124.7m (409ft), Beam 22.5m (74ft), Draught 8.7m (28ft

8in), Full load 10.1m (33ft)

Displacement 15,900 tonnes (15,654 tons)

Propulsion 24 boilers, 2 vertical compound engines

developing 11,780kW (15,797hp), twin screws

Armament

4 432mm (17in) breech-loading guns of 93 tonnes (103 tons),

7 150mm (5.9in) and 4 119mm (4.7in) guns, 4 356mm (14in) torpedo tubes

Armour

Redoubt 483mm (19in), Boiler uptakes 406mm (16in), Conning

tower 102mm (4in), Deck 102–76mm (4–3in)

Range 9260km (5000nm) at 10 knots

Speed 17.8 knots

Complement 701