Pompey’s small flotilla of ships reached the coast near

Mount Casius on 28 September 48 BC, just a day short of his fifty-ninth

birthday. Ptolemy XIII’s army was waiting for him, the boy king splendidly

attired as a commander, but the faction that controlled him had already decided

how to welcome the visitor. Pompey’s friendship no longer seemed so attractive

in spite of his long connection with Auletes. He was coming to Egypt in the

hope of rebuilding his power, which meant that he must take from the kingdom

and had little to give in return. He would want money, grain and men, and some

of the king’s advisers feared that the Gabinians might well be willing to join

him. Ptolemy XIII’s government risked being stripped of the very resources that

guaranteed its power. Even then, Pompey was more than likely to be defeated

again and his conqueror would scarcely be well disposed towards them. Instead,

there was an opportunity to win Caesar’s favour.

A small boat put out carrying a welcoming party consisting

of the army commander Achillas and two Roman officers from amongst the

Gabinians – one of them the tribune Lucius Septimius, who had served under

Pompey back in the 60s. It was a small delegation in an unimpressive craft and

scarcely a mark of honour, but they claimed that the conditions made it

impossible to employ a more dignified vessel or to permit Pompey to bring his

own ship to the shore. Instead, they invited him to climb down and join them,

so that they could take him to be properly greeted by the king.

Pompey agreed. He and his companions may well have been

suspicious, but it would have destroyed what little prestige he had left to

seem frightened by the representatives of a mere client king. His wife Cornelia

and most of his staff watched as Pompey climbed down into the boat and was

rowed ashore. On the way, he spotted something familiar about Septimius and,

addressing him as ‘comrade’, asked whether they knew each other.

The tribune’s response was to stab his old commander in the

back. Achillas joined in the attack, as presumably did the centurion. It was a

brutal, clumsy murder and afterwards Pompey’s head was hacked off and taken to

the king. Another senator was taken prisoner and later executed. Ptolemy’s

warships then launched an attack on the Roman flotilla and several ships were

destroyed before the rest managed to escape. (Thirteen centuries later, Dante

would consign the boy alongside Cain and Judas to the circle of hell reserved

for traitors.)

Caesar arrived in Alexandria a few days later. Ptolemy’s

court must have been aware that he was on his way, because Theodotus was

waiting for him and triumphantly produced Pompey’s head and his signet ring.

These did not prompt the hoped for reaction. Pompey had been Caesar’s enemy,

but before that he had been his ally and son-in-law; he was also a Roman

senator of immense prestige and fame who had been cut down on the whim of a

foreign king and his sinister advisers. It is arguable whether or not Caesar

could have extended his vaunted ‘clemency’ to his most powerful adversary, and

in any case unlikely that Pompey could have brought himself to accept it.

Caesar refused to look at the severed head and wept when he

saw the familiar ring. His horror and disgust may or may not have been feigned.

Cynics said that it was very convenient for him, since his enemy was now dead

and yet someone else would take the blame for the crime. His emotions were

probably mixed, with relief that his opponent could not renew the struggle

mingled with a sadness at the loss of a rival and a former friend. With Crassus

and Pompey now both dead, there was really no other Roman left with whom it was

worth competing.

If the boy king’s advisers were disappointed at Caesar’s

reaction, they were dismayed at what he did next. For the Romans disembarked

and then marched in a column to take up residence in part of the complex of

royal palaces. Caesar was consul and he proceeded in full pomp, with twelve

lictors carrying the fasces walking ahead of him. It was a blatant display of

Roman confidence and authority, suggesting the arrival not of an ally, but of

an occupier. The Alexandrians had a fierce sense of their own independence.

Some of the royal soldiers left to garrison the city immediately protested and

crowds soon gathered to jeer the Romans. Over the next few days, several

legionaries wandering on their own were attacked and killed by mobs.

Caesar was not at the head of a large army and had only two

legions with him. One, the Sixth, was a veteran formation, but after years of

heavy campaigning it now mustered fewer than 1,000 soldiers. The Twenty-Seventh

had about 2,200 men, which meant that it was below half its theoretical

strength. Its legionaries were far less experienced and the formation had

originally been raised by the Pompeians, but had been renumbered when it was

captured and the men swore a new oath to Caesar. To support these Caesar had

800 cavalry, who may well have been the bodyguard unit of Germans he usually

kept with him. Horses are far more difficult to transport than soldiers and

there is a fair chance that most or all of these men were transported without

their mounts.

It is tempting to criticise Caesar for tactlessness in

parading through the city and antagonising the Alexandrians, especially since

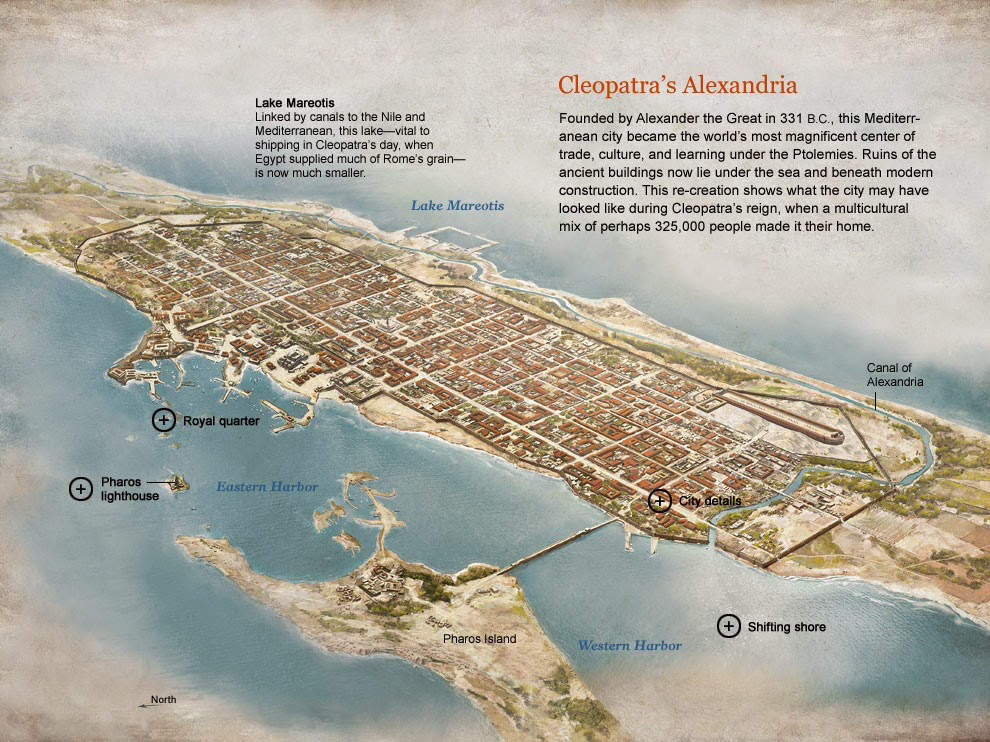

he had so few soldiers and could not hope to dominate a population numbering

hundreds of thousands. Some would see this as habitual Roman disdain for the

feelings of other nations and unthinking arrogance reinforced by his own recent

victories. It was more likely calculation. Caesar had no particular reason to

expect hostility when he came to Egypt, but knew he had only a small force

actually with him. The murder of Pompey was intended to please him, but could

also be seen as a threat. Had he slipped quietly through the streets of Alexandria

the impression would have been one of fear. This is unlikely to have made the

population less hostile, for they had a long tradition of resenting Roman

influence, and it could easily have made them more aggressive.

There were several reasons for him to stop in Egypt.

Although eager to pursue Pompey, he had already paused in several communities,

raising money, dealing with local problems and also placating and pardoning

those who had supported the Pompeians. He needed the eastern provinces to accept

his supremacy and to be stable, for confusion would more easily provide

opportunities for his remaining enemies to continue the civil war. Above all

else, Caesar needed funds. The Republic had been massively disrupted by two

years of conflict and he needed to find the money to ensure that everything

kept running. One major expense was paying his army, which had swollen

massively in size as Pompeian soldiers surrendered. It would have been unwise

to demobilise these men, and even more dangerous if they were not regularly

paid and provided for. The Ptolemaic kingdom was wealthy, offering grain to

feed soldiers and revenue to pay them – the same things that had attracted

Pompey. Caesar needed to be sure that these resources were kept under his own

control and did not fall to recalcitrant Pompeians.

Caesar decided to stay, and soon the decision was reinforced

when a change in the weather made it impossible for his ships to leave. Soon

after landing he had sent orders for more legions to join him, but this would inevitably

take time. At some point, Ptolemy XIII himself and much of his court including

Pothinus also arrived in Alexandria. Achillas and the main army of 22,000 men

remained to the east for the moment, watching Cleopatra’s forces.

The Roman consul informed the king and his court that he and

his sister must disband their forces ‘and settle their dispute through law

rather than weapons with himself as judge’. There was also private business.

Caesar declared that the heirs of Auletes still owed him 17.5 million denarii

according to the agreement of 59 BC and also the loans to Rabirius Postumus,

which he himself had underwritten. He demanded 10 million of this to be paid to

him immediately to support his army.

Pothinus was by now the king’s dioecetes – the same post

held by Rabirius Postumus until he had fled from Egypt – and so the finances

were his direct responsibility. Caesar’s very presence was unwelcome, his

interference in a civil war that seemed virtually won was appalling and his

demands more than could readily be met. It may also have been politically

dangerous for the regime that controlled the king to be seen to give in to

Roman pressure. Pothinus suggested to Caesar that he ought to leave Egypt for

he must have more pressing business elsewhere. For a while – perhaps for weeks

– there was an uneasy truce. Caesar occupied part of the royal palaces and

brought the king and his courtiers under his control to show the people that

the violence was provoked by ‘a few private individuals and gangsters’ and not

by the boy himself. Pothinus met Caesar’s demands to feed his legionaries, but

gave them the poorest grain he could find. Feasts in the palaces were served on

old tableware in direct contrast to the normal opulence of the Ptolemaic court.

It was a double message, telling Caesar that his demands could not quickly be

met and suggesting to the locals that the Romans were bleeding the kingdom dry.

THE LOVERS

At some point, Cleopatra arrived. Caesar barely mentions her

in his own brief account of his time in Alexandria and the fuller narrative

written by one of his officers adds very little information about her. Neither

suggest she played any important role in events and do not even hint at

intimacy between the Roman consul and the Hellenistic queen, but this is in

keeping with the generally impersonal style of Caesar’s Commentaries. Plutarch

and Dio both say that the two had been in contact for some time by messenger,

although they differ over who initiated this.

If Caesar was to arbitrate in the dispute between brother

and sister, then it was natural that he should want to speak to both of them.

Even if he chose to back Ptolemy XIII, he would need to deal with Cleopatra or

risk the civil war between them continuing and thus leaving Egypt unstable and

a source of potential trouble in the future. There was actually little to

recommend such a full endorsement of the boy king and the men who controlled

him. These had so far failed to deliver properly the supplies and money he

wanted, and the attitude of Pothinus was scarcely that of a loyal and suitably

subservient ally. Wherever he had gone, Caesar issued judgements as he saw fit,

usually emphasising his clemency, but always making clear that this was

something he could give or withhold. Backing Ptolemy XIII could easily have

seemed to be giving in to coercion. It would also have aligned him very closely

with Pompey’s murderers. At the very least, he needed to make sure that Ptolemy

and his court worked hard to win his approval.

Until Caesar’s arrival, Cleopatra’s bid to regain power had

stalled and looked likely to end in failure. She clearly lacked the military

power to defeat her brother’s army and there is no trace at this stage of major

political defections to her cause. Caesar had relatively few soldiers with him,

but he represented the power of the Roman Republic in an especially real sense,

since he was victorious in Rome’s civil war. His public disgust at Pompey’s

murder, his refusal fully to endorse her brother’s regime and, most of all, his

willingness to talk to her all suggested that he might be persuaded to favour

her. In a way now traditional for the Ptolemies, Cleopatra quite naturally

wanted to harness Roman power to support her own ambition.

The twenty-one-year-old exiled queen left her army. It is

not heard of again, suggesting that the soldiers dispersed. Perhaps the money

to pay them had run out or, since she did not have enough strength to win,

Cleopatra decided it would be better to appear as the pitiful exile preferring

to rely on Roman justice rather than force. Caesar may have formally summoned

her to Alexandria, and is certainly likely to have known that she was coming.

That did not mean that he could ensure her safe arrival. The Romans controlled

only a small part of the city. Outside that area were many soldiers from the

king’s army. Pothinus, Theodotus and indeed the young Ptolemy himself are

unlikely to have welcomed his older sister. Given the past willingness of the

Ptolemies to slaughter their own family, the more or less discreet murder of a

sister was not only possible, but likely.

There is no good reason to disbelieve the stories that

Cleopatra sailed secretly into the harbour at Alexandria, using stealth or

bribery to avoid her brother’s guards. Only Plutarch tells the famous story

that she was then taken across the harbour in a small boat and into the palace

by a single faithful courtier, Apollodorus of Sicily. They waited until night

fell, so as not to be seen, and the young queen was concealed in a bag used for

carrying laundry – not the oriental carpet so beloved of film-makers.

Apollodorus carried the bag into the palace where Caesar was staying and

brought her to his room. Once there, he could undo the tie fastening at the top

of the bag, so that the material dropped down as the queen stood up, revealing

herself almost like a dancer popping out of a cake.

Some reject the story as a romantic invention, pointing out

that Caesar would scarcely have permitted a stranger carrying a mysterious

burden to come into his room. Yet their earlier correspondence makes it likely

that he knew that either the queen herself or a message was on its way and so

demolishes this objection. Apollodorus’ arrival would not then have been so

unexpected. Others would modify the story, suggesting that instead of hiding in

a bag, the young queen wore a long hooded cloak, throwing this back to show

herself when brought into Caesar’s presence. This is possible, but there is no

direct evidence for it. The appearance of a story in just a single source does

not automatically mean that it is an invention, especially since the accounts

describing Caesar and Cleopatra in Alexandria are quite brief. It was in the

best interest of the king and his advisers to prevent his sister from reaching

Caesar and beyond the latter’s power to guarantee her safety until she was

actually with him. That she came without any ceremony and with at least a

degree of stealth makes perfect sense.