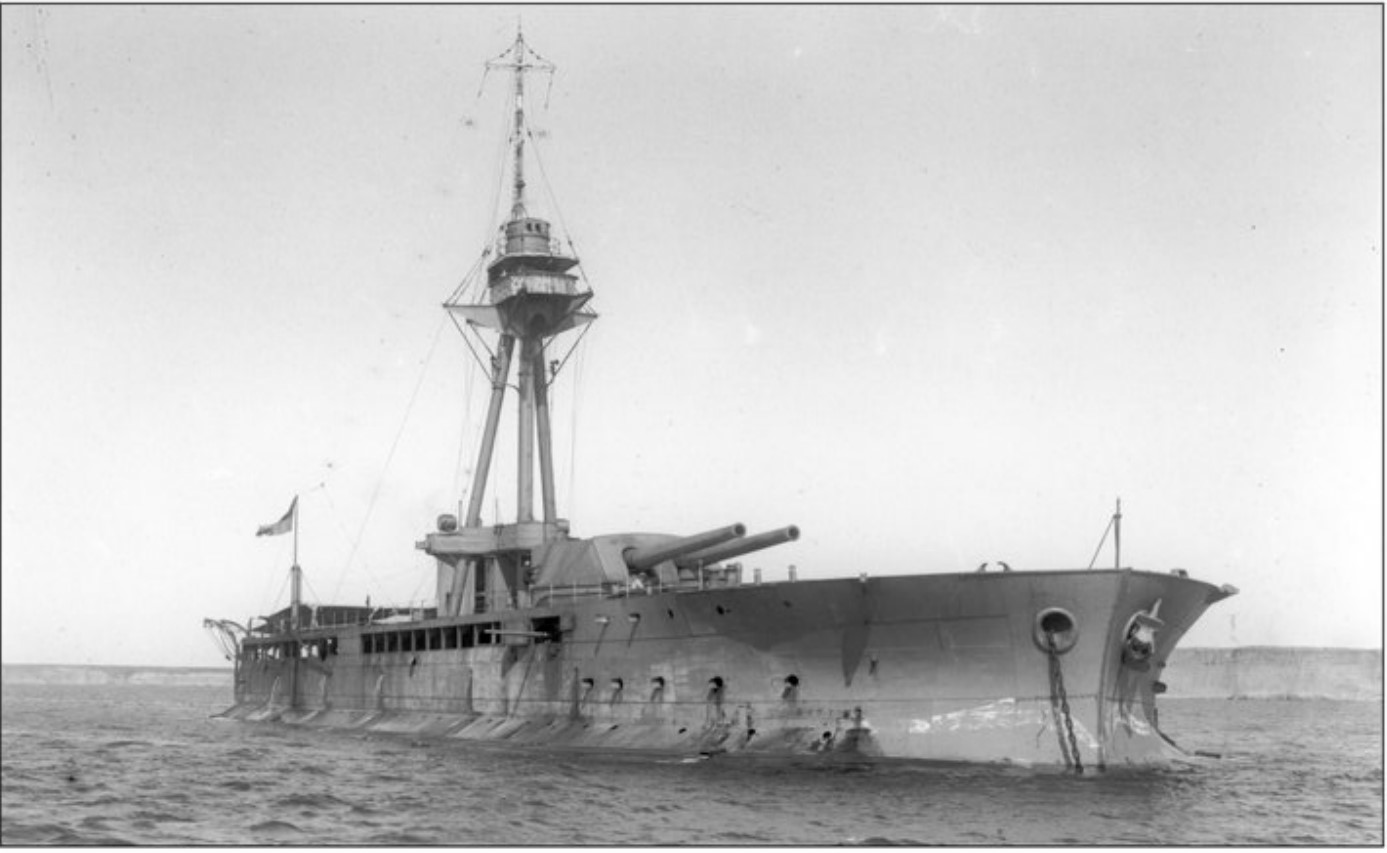

HMS Abercrombie (1914)

This picture shows the stark, uncluttered layout of

the 14 inch monitors. Note the side bulges and the high gunnery control tower

at the top of the tripod mast. Her 14 inch main armament was manufactured by

Bethlehem Steel for battle cruisers to be delivered to Greece, which became redundant

when war broke out. Abercrombie had quite an active war in the Mediterranean,

covering the Gallipoli operations and various Allied operations in the Aegean.

On one occasion she managed to fire her anti-aircraft gun into a store on

petrol on deck, causing a sever fire. Luckily the damage was minor.

HMS Humber

This picture shows Humber in her original configuration.

Later she had a second turret with a single 6 inch gun mounted on the after

deck, and the 4,5 inch howitzers were moved onto the upper deck. It is easy to

see that her designers intended her for riverine use only. Any sort of sea

would swamp the lower decks, and her lack of draft would cause her to skid

sideways in a crosswind. However her low profile made her a difficult target

and she and her sisters all survived the war with no serious damage.

While the first two monitors were active on the coast of

Africa events of far greater importance were taking place in the Dardanelles.

It was to prove one of the most disastrous actions ever undertaken by British

arms. After Troubridge had been sent home in disgrace for letting Goeben escape,

Admiral, Sir Sackville Carden, was placed in command of the force which was to

find her, if she dared to emerge from her Turkish lair, and sink her and her

consort. His task was not an easy one.

The Narrows, the passage leading from the Aegean to the Sea

of Marmora was protected by powerful forts on Cape Helles and Kum Kale and by

further batteries of heavy guns at Kephez and Chanak points. Even more

dangerous than these was a dense minefield consisting of almost 400 moored

mines in the channel which was less than 1 mile wide.

The Straits are dominated by hilly, broken country and are

only about 5 miles wide at their widest point. Ships in the Straits are liable

to shelling from the forts at the entrance and from others established at

strategic points along the shoreline. The forts themselves were venerable

structures, but around them had been built, with German advice and help, modern

well-designed earthworks concealing heavy guns which could survive anything

short of a direct hit on the gun itself. In the hillsides looking down on the

Straits were concealed mobile batteries of field guns and howitzers. These were

not big enough to damage heavily armoured ships much, but they could be fatal

to unarmoured vessels such as trawlers or destroyers. There were also powerful

mobile searchlights to spot for the guns at night. Through the Straits runs a

current of anything from 2 to 4 knots, constantly running out into the

Mediterranean. This current runs strongly in the centre, but is weak or

nonexistent near the shores, especially the southern (Asiatic) shore. There

could scarcely be a more suitable stretch of water for defensive mining.

The Narrows of the Dardanelles had been mined before the

war, in mid-1914, but merchant ships were allowed to pass through a clear

channel, accompanied by a Turkish pilot. In September of that year however a

British patrol intercepted a Turkish destroyer just outside the Narrows and

found German sailors on board. The resulting diplomatic incident caused the

Turks to close the gap in the minefields and declare the Narrows closed,

cutting Russia off from the Mediterranean. On 31 October Turkey joined the war

on the German side. Immediately the minefields were reinforced, and the shore

based heavy artillery and mobile field guns were increased in number. Their

crews were rapidly stiffened by newly arrived German artillery specialists.

More powerful searchlights were sent to cover the minefields and keep away

sweepers. The old battleship Messudieh was sent into the Narrows to provide extra

protection and fire power. Carden made two attempts to destroy forts guarding

the entrance, doing considerable damage, but failing to silence them

completely. The protective earthworks, reinforced with German help, ensured

that although the guns might be dismounted and the gunners evacuated during a

daylight bombardment, it was a relatively simple matter to restore them during

the hours of darkness. Only a direct hit on the gun itself would effectively

destroy it. The only notable Allied success was the sinking of Messudieh by the

submarine B-11, which managed to dive below the mines and stem the current in

the Narrows, although her underwater speed was only 4 knots.

By the end of January 1915 the War Cabinet had determined to

adopt a more aggressive policy with the hope of forcing Turkey out of the war

altogether. A fleet of ten British and four French old pre-dreadnought

battleships would force the Narrows and steam towards Constantinople, protected

by minesweepers and destroyers. The entrance forts would be silenced by their

guns, supported by the great 15 inch main armament of Queen Elizabeth, the

navy’s most modern and formidable battleship, which had been sent out by the

Admiralty to provide support. She was not allowed to penetrate the Straits themselves

– that would be too risky – but she could bombard from far off. Unfortunately

accurate long-range indirect gunfire was impossible without good spotting from

the air, and this, for various reasons, was not available. Carden had proposed

this scheme and it was endorsed by the War Cabinet in the face of opposition

from Fisher, the First Sea Lord who correctly foresaw the danger from mines and

the problems associated with attacking coastal artillery from the sea.

The attacks on the forts commenced on 19 February, and by

25th most of the guns in the outer forts had been destroyed by the ship’s

bombardment and by Royal Marine landing parties. The fleets were now able to

move into the mouth of the Straits and silence the inner forts guarding the

entrance to the Narrows. This was less successful, once again the Turkish

gunners took cover when they were being hit by naval gunfire, only to emerge as

soon as it ceased, furthermore, as the ships entered the restricted waters,

they came within range of the mobile field guns. These could not do severe

damage to heavy ships but they did make matters extremely difficult for the

intruders, and forced the unarmoured destroyers to keep moving so as to avoid

being hit. Firing on the inner forts at long range did little damage to them

and it was clear that the warships would have to get closer for their assault

to be effective.

The first section of the Strait was clear of mines, but to

move further in and tackle the second pair of forts at the entrance to the

Narrows themselves at close range, the minefields would have to be swept. To do

this, North Sea trawlers had been provided, and these were given light armour

to protect them from small arms fire. They were manned by their regular RNMR

(Royal Naval Minesweeping Reserve) crews. It had originally been intended to

supplement these with “mine bumpers” – cargo ships with reinforced hulls filled

with concrete which would clear a path for each capital ship by steaming

through the field blowing up mines as they went. These were not eventually

provided. (Strangely the British did not make much use of reinforced mine

bumpers to protect capital ships in either world war. The Germans used them,

calling them Speerbrechers, extensively in both). The trawlers had to battle

against the strong currents in the Straits, so that their speed over the land

was only 2 or 3 knots making them easy targets for guns on shore. To give them

some protection from shore batteries, the sweepers were detailed to work at

night and were supported by destroyers and a light cruiser. On 1 March they set

off on their first mission. Before they reached the minefield they were

detected from the shore, and illuminated by brilliant searchlights, making them

an excellent target for the shore based field guns. No trawlers were hit, but

the fisherman crews hastily withdrew. They had not been trained for work under

fire and were badly shaken by the experience. Who can blame them? Their little

ships were almost stationary in the strong current, and a single hit from the 4

inch or 6 inch field guns would have proved fatal. Three more attempts were

made, but with no result. A different tactic was then port to try to silence

the tried. This time the trawlers steamed up stream as fast as they could go,

with their sweeping gear stowed, then turned and swept down with the current. A

handful of mines were recovered, but some of the crews were so scared,

especially when they had to turn round and deploy their sweeps under fire, that

they did not attempt to sweep at all. After two weeks of failure the regular

navy was becoming disillusioned with the fishermen-sweepers. One trawler had

been sunk and several damaged, but no one had been killed and there were open

accusations of cowardice levelled at the RNMR. On 13 March one final attempt

was made with the sweeper crews stiffened with Royal Navy volunteers and

supported again by fire from a battleship. This was even more disastrous. The

supporting cruiser Amethyst was badly hit, suffering twenty-four men killed,

and several trawlers were severely damaged, also suffering casualties. A few

mines were swept, and some more were found floating free in the Straits.

Possibly these had been deliberately floated down by the Turks. They were

easily dealt with and in future operations small picket boats operated

alongside major ships to deal with any more “floaters”. This was a pretty high

risk operation for the picket boat’s crews, exposed as they were to the fire of

field guns on shore. Some of them were actually fitted with explosive sweeping

wires and seem to have accounted for several mines.

By this point Carden was coming under severe pressure from

Churchill who urged him to make progress regardless of casualties. After all,

he argued, thousands were dying on the western front and the Dardanelles operation

could relieve pressure on the hard-pressed troops in France. It was well worth

hundreds of casualties among the minesweepers to force the passage and achieve

their objective. The minesweeper crews, not unnaturally, did not agree.

The unfortunate Carden fell sick and was replaced by Admiral

de Robeck, who had been his second in command. He resolved to continue the

attack but to use a new tactic, devised by Carden, of making a daylight attack

on the shore batteries and to sweep the minefields as he went. He intended to

use his full force now consisting of thirteen British and four French

battleships, and one dreadnought battle cruiser. The battleships were all

pre-dreadnoughts except for the super dreadnought Queen Elizabeth, still

attempting to make her indirect fire from outside the Narrows effective. A

heavy bombardment at long range would attempt to silence the shore batteries

and suppress the guns in the forts, then a second wave of battleships would

steam close to the forts and complete their destruction, covering the passage

of trawlers into the minefields. The warships could then follow the sweepers

and force their way right through the Narrows. Some of the attendant destroyers

were adapted to carry light sweeping gear.

The action took place on 18 March. At first things went as

planned, the armada steamed into the straight and advanced towards the forts on

Kephez Point, Turkish shore batteries replied vigorously, but the only ship

badly damaged was the French Gaulois, which had to be beached. Gradually the

warships got the better of the shore guns, and things were going according to

plan when the advancing second line of battleships, steaming close to the forts

to blast them at close range, suffered a series of appalling disasters. Bouvet

(French) and Irresistible (British) were sunk by mines where there should have

been none, and the battle cruiser Inflexible was severely damaged by gunfire.

Shortly afterwards the battleship Ocean was disabled by gunfire and a mine

strike and had to be abandoned. Once again, to the disgust of the naval

officers present, the trawlers fled from the scene under heavy bombardment. Two

of them had tried to deploy their sweeps and steam upstream. They dealt with

three moored mines, but fire from the shore was too much for them and they

abandoned their attempt in spite of orders and encouragement shouted from the

picket boats and destroyers. It was impossible now for the battleships to

proceed into the Narrows and de Robeck had no alternative to withdrawing his

battered force. What had happened was that a Turkish mine expert, Lieutenant

Colonel Geehl, had anticipated a close range attack on the inner forts and had

taken a small fast steamer Nousret down the Narrows and laid a small field of

twenty mines in exactly the right position. Hence an insignificant little

civilian craft had brought about the sinking of three major warships and the

disablement of a dreadnought battle cruiser. From that day on de Robeck was

determined that no further attempt could be made to force a passage into the

Sea of Marmora, until at least the European shore was held by the Allies. The

Admiralty supported him and the scene was set for the even greater disaster of

the landings on the Gallipoli Peninsula.

This sorry performance made the navy keener than ever on the

idea of the monitors. If big gun monitors, such as the 14 inch, 12 inch and 15

inch vessels then being built, had been available to get close to the coastal

guns, things might have gone differently, or so it was argued in Whitehall. The

monitor’s big guns could have been brought to bear on the forts from close

range, as they could operate in shallow water, close under the enemy guns, and

their mine defences and shallow draft would have at least reduced the

possibility of their sharing Ocean’s fate. Monitors must be got to the Aegean

as quickly as possible.

Humber, it will be recalled, had remained at Malta while her

sisters were making their way down the African coast. A small ship with only

three 6 inch guns and two howitzers she seems to have been overlooked, in any

case her mission had been to act as a river craft when the march up the Danube

began. Then the great events taking place at Gallipoli brought a sudden change.

General, Sir Ian Hamilton, who had arrived just in time to

witness the events of the 18 March, and was to command military operations on

land, had agreed with de Robeck that the army would have to occupy the northern

shore and destroy the enemy forts once and for all before any further naval

assault on the Narrows could be contemplated. Churchill, as First Lord of the

Admiralty objected strongly to this scheme and ordered de Robeck to resume his

naval offensive but the order was countermanded at the insistence of Fisher.

75,000 troops had been earmarked for landing at Gallipoli, consisting of

Australians and New Zealanders then training in Egypt, the British 29th

Division and a French North African Division. Hamilton had been assured that

his task would be easy. The whole peninsular would be swept by naval gunfire,

the Turks would put up only a token resistance as the bulk of their troops

would be busy elsewhere and the affair would be over in a few weeks. It appears

that no one had taken the trouble to find out that the ground on which the army

would be fighting was rugged and desolate, rising in places to 1,000 feet in

height and ideal for defensive warfare. The Turkish army was indeed ill

equipped and poorly trained, but it was stiffened by highly professional German

officers and supplied with some excellent German weapons, especially machine

guns and artillery. In command was the redoubtable General Otto von Sanders.

The Allied army took some time to organise itself, giving

von Sanders the opportunity to make an excellent job of fortifying the

peninsular. The landings took place on 25 April, gradually and with terrible

losses, the troops battled their way inland constantly supported by the guns of

the fleet. It soon became clear, however, that naval support, critical as it

was to the campaign, could not be maintained. For the first month all went well

for the fleet, although their bombardment of the enemy positions ashore was not

nearly as effective as everyone had hoped, due to the rugged terrain and the

excellent defences built by the Turks. Commodore Roger Keyes, Chief of Staff to

de Robeck, who was the strongest advocate of a further attempt to force the

Narrows by the now much increased Allied fleet, confessed to being ashamed of

the relative inactivity of the navy while so many soldiers were dying ashore.

Then, on the 12 May the battleship Goliath, lying just 100 yards off-shore and

waiting to be allocated a new target, noticed an unfamiliar looking destroyer

approaching her during the night. The officer of the watch challenged the

stranger, but he was too late. The ship was the Turkish destroyer Muavenet, her

German captain had skilfully brought her down the Narrows, close inshore on the

European side and she let loose three torpedoes at close range. Goliath rolled

over and turned turtle, rapidly sinking. There was a strong current running at

an estimated 4-5 knots so men attempting to swim ashore were all carried away

and drowned. Out of 750 men on board only 180 were saved by boats from nearby

ships. This disaster set off an almighty row in the Admiralty. Fisher, who had

always disliked the whole idea of the Dardanelles campaign, was in a fever of

worry about the possibility of Queen Elizabeth, the super dreadnought,

suffering the same fate. Churchill pacified him by agreeing to withdraw Queen

Elizabeth and replace her as soon as possible with 14 inch monitors. This was

set in hand, but as soon as the War Office heard of it Lord Kitchener objected

violently. “If she goes,” he said, “we may have to consider . . . whether the

troops had better be pulled back to Alexandria”. The navy, it seemed to him,

was deserting the army in its hour of need. Fisher was adamant and stated that

if Queen Elizabeth did not sail that very night he himself would walk out of

the Admiralty. Tempers were temporarily cooled by the promise of sending still

more monitors and bringing home some more battleships, but this had the effect

of annoying Fisher again as he had hoped to use the monitors for his scheme for

a landing on Germany’s Baltic coast. He resigned in a fury and played no

further part in the war.

The navy’s problems were only just beginning however, on 17

May U.21 had been sighted passing through the Straits of Gibraltar. Admiral de

Robeck was informed but seems to have taken no new precautions. On 25th the old

battleship Triumph was standing off Anzac Beach in full view of both armies.

She suddenly rolled over and sank, a victim of the first of U.21’s torpedoes.

The Turks in their trenches shouted and danced for joy as she went down,

mercifully with the loss of only fifty-six men. The following day Majestic,

another ancient battleship, was preparing to fire on the Turkish trenches when

a seaman said to an officer “Look Sir, there is a submarine’s conning tower.”

“Yes” he replied, “and here comes the torpedo.” The old battleship rolled over and

lay in the shallow water, her hull just awash. The Allies had clearly lost

control of the waters close to the peninsula. The following day a German

officer, looking down from the heights, was astonished to see the water which

had once been alive with British warships almost deserted. The fleet had

retired to safe anchorages around Murdros Island leaving the hard-pressed

troops ashore almost without heavy gun support. It was whispered in the

trenches that the navy had run away.

Then someone remembered Humber. She was at Malta, she was

expendable, there didn’t seem to be much prospect of sending her up the Danube

and if she could replace the heavy warships withdrawn she would at least be

better than nothing. At the same time some cruisers, hastily fitted with

anti-torpedo bulges, were pressed into the bombardment squadron and sent to

cruise off the peninsula. On 4 June Humber started to bombard an especially

troublesome nest of Turkish artillery hidden among the olive trees in a ravine

called Axmah. Her intervention was most welcome to the beleaguered troops on

shore and she was able to provide effective bombardment with her 6 inch guns

and also use the two 4.5 inch howitzers for high trajectory fire into ravines

and trenches. There was a problem the following day when a premature detonation

damaged one of her forward guns, but she remained in action until December,

becoming a bit of a favourite with the Anzac troops, who were short of

artillery of their own, and were constantly pestered by Turkish guns hidden in

olive groves which enfiladed the beaches over which all their reinforcements

and supplies had to travel. Working very close to the shore she was often fired

on by enemy field guns, but never seriously damaged. After the loss of the

three battleships, the bombardment squadrons of monitors and cruisers were

careful to deploy their torpedo nets and were not troubled by enemy submarines

or destroyers. They put up an impressive performance.

The bitter rows in London about the deployment of Queen

Elizabeth, and the possibility of attacks on the German coast had resulted in

the dispatch of the first of the specially built 14 inch monitors, the four

“Generals” with the American built 14 inch guns, to join the makeshift fleet

supporting the Dardanelles operation. Their departure was delayed by the need

to replace the wrongly designed propellers and correct other faults found on

trials. They were so slow and underpowered that they had to be towed for most

of the 3,000 mile voyage. Abercrombie, towed by the old cruiser Thesus set off

on 24 June, Havelock, Raglan and Roberts leaving a few days later also under

tow. They arrived at Murdros in late July, and the sight of their massive

turrets must have put new heart into troops on shore.

As soon as she arrived Abercrombie targeted ammunition dumps

on shore at Eren Keui on the Asiatic shore, the Turks replied and she was hit

by a heavy shell which luckily did not explode. Her own fire seems to have been

ineffective, possibly because of lack of proper spotting from aircraft. It had

always been intended that large monitors should carry their own spotter planes,

but these were found to be a nuisance because they were a fire hazard, and

because they had to be removed every time the guns were fired as the shock

damaged them. Roberts joined Abercrombie in mid-July and she was tasked to

destroy heavy gun batteries on the Asiatic shore, near Kum Kale, which were

able to fire on the flank of the troops trying to force their way forward up

the Cape Helles peninsula. To do this she anchored off Rabbit Island. This was

to be a favourite berth for monitors for many months, it was over 10 miles from

their target, well within range of the 14 inch guns but hidden behind the

island and far enough away from the enemy to be almost immune from counter

fire. The monitor’s own fire was indirect, they could not see their targets,

but aiming marks on the island enabled the guns to be correctly aligned. The

Turkish batteries were never totally destroyed, but their fire was much

reduced. Occasionally aircraft attempted to bomb the monitors but they did

little damage.

On 6 and 7 August the Allies landed reinforcements at Sulva

Bay, this action was supported by the final two 14 inch monitors, Havelock and

Raglan and by some of the small monitors which had now arrived on the scene

straight from their builders. Once again the main targets were mobile Turkish

batteries and troop concentrations. Naval support was critical to the success

of the landing, although on one occasion a naval gun, firing prematurely,

landed a shell among British troops causing four casualties. Havelock moved

into Sulva Bay itself, giving direct close fire support to troops, but it soon

became clear that ammunition expenditure was becoming excessive and had to be

curtailed. It seems that the process of spotting and communication between the

ships and observers on land and in the air during these operations left

something to be desired. The lessons being learnt at almost the same time by

Severn and Mersey about developing very close relations between the airmen and

the gun crews, working out easily understood codes and keeping the spotter’s

job as simple as possible, were not so easy to apply in the complicated

situation of the Gallipoli campaign. Frequently the monitors operated very close

to the shore in support of ground forces, and were in range of Turkish guns.

Most of these were 75mm (approximately 12lb.) which could do little damage to

the ships. Splinters could of course kill crewmen in the open, but only on rare

occasions was anyone needed on deck during firing operations. There were some

bigger guns as well, but Turkish shooting was not the best and no serious

damage was done. Occasionally very long range bombardment was called for, and

for this the ships would be heeled over by flooding the anti-torpedo bulges so

as to give extra elevation. This put extra strain on the guns and turrets

reducing the life of the gun barrels, so the technique had to be used

sparingly.

As 1915 progressed stalemate developed on the peninsula. The

Sulva landings had broadened the Allied front but had been contained by the

Turks, who held firm on the high ground. Also the 14 inch monitors were

starting to show some weaknesses, especially in their steering engines and, in

some cases, in their much abused gun barrels. A repair ship, Reliance, was at

Murdros and worked hard to keep them in action. It was obvious that the

monitors would never be able to force a passage up the Narrows as they could

barely stem the current. In the autumn, as more of the small monitors appeared

on the scene, a re-organisation of naval forces was undertaken and four

bombardment divisions were formed comprising:

The four 14 inch monitors.

Ten 9.2 inch small monitors M15-M23 + M28.

Five 6 inch monitors M29-M33 + Humber.

Four bulged cruisers.

Gradually, with experience, the fire of the big monitors

became more effective. Roberts remained off Rabbit Island, Abercrombie

supported the left flank of the Cape Helles beachhead, firing on batteries on

the slopes of Achi Baba. Her accurate and effective fire drew heartening

compliments from senior army officers. Havelock seems to have specialised in

long range bombardment, firing right over the peninsula, on one occasion

hitting an armaments dump 17,000 yards away eleven times out of fifteen shots.

Raglan continued to support the Sulva Bay position then moved off on another

mission.

Serbia was being threatened by Bulgaria and an Allied

contingent was landed to support the Serbs. A small naval squadron was

dispatched to the Aegean in support, Raglan’s heavy guns were considered a

useful addition to the cruisers and destroyers involved, but in the end there

was very little fighting (see map 4).

Although it became plain to most observers by the end of the

summer of 1915 that the land battle at Gallipoli was making no progress, the

momentum of the campaign caused it to drag on until December and more and more

monitors of various kinds started to appear as the campaign progressed. The

small monitors being faster and handier than the heavy gun ships were particularly

effective at harassing the coastline of European Turkey. The 9.2 inch guns, old

as they were, proved to be most accurate and effective weapons, although their

recoil was such that the little ships lurched violently each time they were

fired. They were invaluable in suppressing enemy counter fire aimed at their

big sisters and in firing at long range at enemy ships in the Narrows. Their

9.2 and 6 inch ammunition was not in such short supply as 14 inch so they could

be more liberally used. One exciting side show action was carried out against

Bulgaria during October when the 9.2’s of M15, M19 and M28 bombarded Bulgarian

railway installations and barracks at Dedeagatch. Much damage was done and the

Bulgarians, fearing an Allied invasion, were forced to adopt a defensive

posture in place of supporting their Allies against Serbia.

In spite of their relative simplicity the small monitors did

present some problems for the fleet’s engineers. The diesel engine ships often

suffered funnel fires due to hot exhaust gasses setting fire to soot deposits

in the funnels, although the results of these could be alarming they were

seldom serious. M19 suffered a more serious problem when she was moored

alongside Abercrombie and joining in a bombardment of the slopes on Achi Baba.

Suddenly she appeared to be in the middle of a colossal explosion and chunks of

metal rained down all round her. What had happened was that a shell had

exploded inside the bore of her gun blowing it to pieces and setting fire to

the magazine. Acting promptly and coolly the crew flooded the magazine and got

the fire under control. Two men had been killed and another injured by a

fragment which came in through the slits in the armoured conning tower, six

others suffered serious burns. The ship managed to limp to Malta where she was

repaired. Another casualty was M30, patrolling off Smyrna (Izmura) in Asiatic

Turkey. She was hit by a well concealed heavy gun onshore and caught fire. This

time the fire spread to the fuel and she had to be abandoned. Her guns were

eventually recovered and the hull was blown up.

In December the eventual abandonment of the Dardanelles

commenced and it was completed by the 8 January. The withdrawal had become

strategically inevitable. The army was making almost no progress on land, and

losses were mounting steadily, not just from enemy action, but from the bitter

cold and freezing rain storms which started in October and grew steadily worse.

Bulgaria’s entry into the war meant that there was even less prospect than

before of a thrust up the Danube to attack the flank of the Austrian army.

Hamilton, who had gloomily forecast that half his men would be lost if the

force was evacuated, was relieved of his command. His replacement, General, Sir

Charles Monro, arrived fresh from the western front, made no secret of his

belief that the whole Gallipoli affair was a waste of time and of resources

desperately needed elsewhere. Commodore Roger Keyes still believed that a last

attempt to force the Narrows should be made by the fleet reinforced by fast

minesweepers, but now that Arthur Balfour had taken over the Admiralty from

Churchill, and de Roebeck remained staunchly opposed to any such venture,

Keyes’s appeals fell on deaf ears.

In sharp contrast to most of the campaign, the evacuation was

brilliantly handled with rifles and artillery arranged to continue firing after

the troops had withdrawn so as to disguise the fact that the withdrawal was

taking place. Almost all the monitors, including two of the new 12 inch ships

which had just arrived from Britain, together with the bulged cruisers, had

been assembled to cover the final evacuation from the beaches and the whole

operation was completed without a hitch and with minimal casualties. Of the

half a million men involved in the Gallipoli expedition almost half had been

wounded or became sick, 50,000 died.

This ill-conceived campaign had shown up very well the

strengths and weaknesses of the big gun monitors. They had provided useful fire

cover and destroyed some important enemy installations but their interventions

had not been in any way decisive and their co-ordination with ground forces had

not always been good. They were so slow that they were utterly useless for the

operation which it had been hoped they could perform – forcing the Narrows.

Furthermore their appetite for heavy ammunition was a serious embarrassment on

this station, distant as it was from Great Britain. For most of the campaign

the 14 inch monitors had to be limited to two or three rounds per day. Land

battles in the 1914-1918 war were won by using massed artillery pouring

thousands of rounds down in a hail of fire on enemy positions, and this could

not be achieved using the great guns of the monitors on this distant

battlefield. Introduced as a cheap, quickly constructed force which would allow

Britain to project military might overseas and carry the battle to the enemy,

these limitations of the monitors must have been a sore disappointment to

everyone involved. Conversely the small monitors had been reasonably successful.

Their guns had been effective, especially the old 9.2s and because they were

small and readily mobile they had done everything that could be expected of

them, effectively harassing enemy lines of communication and making movement by

land or water along the coastline extremely difficult. They were also useful

for patrolling the narrow seas between Greece and Turkey, keeping a lookout for

suspicious movements, a task for which they were to be used extensively in

later campaigns.