■ The

Legions against the Phalanx

Rome had clashed with Philip V of Macedon when he cautiously

allied himself with Carthage. Roman military commitments had then led to a

compromise peace, but war was renewed two years after Zama. The Romans did not

wish for a bad neighbour on the other side of the Adriatic, let alone one who

often emerged as the ally and patron of pirates. Pretexts for intervention in

Greek and Macedonian affairs were not far to seek. Since 273 BC, Rome had been

on friendly terms with the Ptolemaic dynasty of Egypt. Ptolemaic succession

difficulties had now arisen, and with avid opportunism Philip had allied

himself to Antiochus III, who ruled Syria – the rump of the Seleucid empire –

in an attempt to seize the Ptolemies’ overseas possessions. As usual, in a

struggle between the successor powers, would-be neutrals were reluctantly

involved, and Rhodes and Pergamum, a Greek Asiatic kingdom of culture which had

recently stemmed Celtic inroads and defied the Seleucids, appealed to Rome.

The Roman commander who eventually took charge in Greece was

Titus Quinctius Flaminius, an ardent philhellene. He finally defeated Philip at

the battle of Cynoscephalae in Thessaly (197 BC). Cynoscephalae in Greek means

“dog’s heads”, the shape of local hillocks suggesting the name. The uneven

ground seriously hindered the Macedonian phalanx, but heavy mist early in the

day also hampered Roman mobile tactics. On both sides, the right wing was victorious,

but the scales were tipped in Rome’s favour by a tribune whom history has not

named. On his own initiative, he diverted 20 maniples from a point where

victory was already assured, to surprise the enemy phalanx in the rear.

Flaminius, thus victorius, was welcomed as liberator of Greece. Subsequently,

however, in 183 BC, he appeared in a less generous light, attempting to

extradite the aged Hannibal, who as a harmless exile now lived in the Asiatic

kingdom of Bithynia. Hannibal took poison. Even Roman senators did not approve

Flaminius’ action, condemning it as officious and harsh.

Rome’s terms with Philip were not unduly severe, but war

already loomed with Antiochus, his eastern ally. The logic of Roman military

expansion is clear enough. For the sake of security and trade, Rome wanted

peace in the eastern Mediterranean, but since she could not countenance any

power strong enough to act as peacemaker, she had to exert her own strength in

this capacity. Antiochus neglected rather than suspected Roman power and he

had, perhaps tactlessly, employed the exiled Hannibal in a military capacity.

In the war which followed, Antiochus’ fleets were unable to resist the Roman

grappling and boarding tactics which had destroyed Carthaginian naval

supremacy. On land, he was defeated first at Thermopylae (191 BC), then at

Magnesia near Sipylus (190 BC), in Lydia. This last battle proved decisive. The

Roman legions, as at Zama, had the advantage of good allied cavalry support,

provided here by Eumenes, king of Pergamum. In their desire to tempt Antiochus

from his defensive position, the Romans exposed their right wing, but Eumenes’

attack anticipated and threw into confusion the outflanking movements by

Antiochus’ heavily armoured cavalry. The Roman left wing was thrown back by a

charge of Oriental horsemen under Antiochus’ personal leadership, but the

victors in this section of the field continued their pursuit too long and left

the central phalanx unsupported. The phalanx, stationed in dense formations, at

intervals, with elephants filling the gaps, was broken when the Romans

successfully stampeded the elephants and breached the line.

The peace terms which followed Magnesia reduced Antiochus to

impotence as far as the Mediterranean was concerned. But Rome fought a third

Macedonian war with Perseus, son of Philip V. The decisive battle which finally

established Rome as arbiter of the eastern Mediterranean world came at Pydna in

Macedonia (168 BC). The pikemen of the Macedonian phalanx were again at a

disadvantage on broken ground and the Roman legionary swordsmen were able to

exploit gaps in their ranks. Roman tactical flexibility was, on this occasion,

well turned to account by the generalship of Lucius Aemilius Paullus, son of

the consul killed at Cannae.

Rome’s victories in these eastern wars cannot be understood

unless it is realized that the ponderous Macedonian phalanx of the second

century BC differed completely from the original flexible and mobile phalanx of

Philip II and Alexander the Great. With the growing tendency towards heavier

weapons and armour, it in effect reverted in character to the rigid Greek

phalanx of the fifth century BC. At Cynoscephalae, the phalanx, attacked by

Flaminius’ tribune in the rear, had been unable to wheel about even to protect

itself. This helplessness compares significantly with the alacrity of

Alexander’s phalangists at Gaugamela, who faced sharply about to rescue their

baggage train from a Persian breakthrough.

Ever since the days of Camillus, when the maniple formation

had been introduced, the Romans, unlike the Macedonians, had developed

consistently in the direction of flexibility. To this development, the genius

of Scipio Africanus had given great impetus, and the commanders who fought

Rome’s eastern wars in the second century BC had thoroughly absorbed his

tactical principles.

■

Weapons and Tactics

The confrontation between the legion and the phalanx raises

questions as to the comparative effectiveness of sword and pike. The pike, of

course, had the longer reach, but the sword was a more manageable and less

cumbersome weapon, giving greater opportunity for skill in its use.

At Pydna, the Italian allies serving under Aemilius Paullus

hurled themselves with reckless heroism at the enemy pikes, trying to beat them

down or hew off their points. But they sacrificed themselves in vain; the pike

points pierced their shields and armour, causing terrible carnage. The phalanx

was eventually shattered as the result of cool tactical judgment. Paullus

divided his force into small units with orders to look for gaps in the pike

line and then exploit them. The gaps appeared as a result of the rough ground

which prevented the phalangists from moving with uniformity and keeping

abreast. Forced at last by the infiltrating legionaries to abandon their pikes

and fight at close quarters, the Macedonians soon discovered that their small

swords and shields were no match for the corresponding Roman arms.

The Macedonian dynasts who relied upon the phalanx were

perfectly aware of the dangers to which it was exposed and their awareness

explains the hesitation to join battle that marked their encounters with the

Romans. The phalanx was considered secure while it remained stationary. The

Romans consequently tried to tempt it into action but, even so, had to beware

lest in provoking an attack they rendered themselves too vulnerable.

Gaps, of course, might be opened in the enemy lines by the

pilum. Something could be expected from the volley of weighted javelins with

which the legions normally commenced a battle. But against this, the

phalangists were heavily armoured: Perseus’ phalanx at Pydna drew its title of

“Bronze Shields” from the round bucklers which his men wore slung round their

necks and drew in front of them as fighting started. But wooded or uneven

country was the legionary’s best chance against armies of the Macedonian type.

The Romans had learnt their lesson as early as the battle of Asculum against

Pyrrhus, where they had been able to withdraw nimbly before the intact line of

the phalanx, only to rush in where ground obstacles created ready-made breaches

in the pike formation.

A similar confrontation of sword and spear is to be found in

Italy in 225 BC, when, in the period between the First and Second Punic Wars,

Rome fought with invading Gauls at Telamon in Etruria. On this occasion the

Romans were the spearmen and the Gauls the swordsmen. The Roman general, in

fact, placed some of his triarii in the front line in order that their spears

might blunt the Gallic swords: the Gauls, like the Italian soldiery at Pydna,

tried to parry or hack away the spear heads. Gallic swords were sometimes made

of very soft iron. In fact, Polybius tells us that the Gallic sword was so soft

that after striking a blow the swordsman was obliged to straighten the bent

iron against his foot. Incidentally, Plutarch tells the same story of poorly

tempered Gallic swords in his Life of Camillus. The Gauls seem to have relied

on carrying all before them at the first onset; this is understandable if their

swords were rendered so quickly unserviceable. Perhaps the defect was localized

in certain tribes where ironworking had not advanced beyond a primitive stage

or where facilities for obtaining good weapons did not exist. At Cannae,

although the Spaniards in Hannibal’s army fought with their short thrusting

swords, the Gauls preferred their normal, unpointed, slashing weapons. However,

there is no mention here of soft iron and the Gauls, so far from despairing

when immediate victory eluded them, doggedly retreated in the face of Roman

pressure, until Hannibal’s tactical plans matured. In any case, one feels that

Hannibal’s astute generalship would not have permitted the use of soft iron

weapons among his troops.

Polybius gives a graphic account of the Gallic invaders of

225 BC. Although the rear ranks wore cloaks and trousers, the huge men of the

front line, with traditional bravado, fought stark naked save for their gold

collars and armlets.

The sight was formidable, but the prospect of acquiring the

gold stimulated Roman efforts to kill the wearer. The shields of these reckless

fighters were not large enough to protect them; the bigger the warrior, the

more exposed he was to the Roman pilum. The Roman legionary regularly carried

two pila, one more slender than the other, perhaps for convenient reservation

in the shield hand. The long, barbed, iron head was riveted so securely to the

shaft that it would break rather than become detached from the wood. However,

this very solidity was later felt to be a mixed blessing, for a spent missile,

intact, could be recovered and used by the enemy. Technical measures were taken

to neutralize the danger.

■

Sackers of Cities

Advantages cease to be advantages when one becomes too

dependent on them. Rome’s dependence upon overseas power and wealth led to

neglect of the old self-sufficient Italian economy. Roman overseas wars assumed

the aspect of predatory exploits rather than peace-keeping missions; the

struggles of the later second century BC characteristically terminated in the

pitiless sack of cities rather than decisive battles followed by peace terms. When

the Achaean League and its ally Corinth revolted against the Roman settlement

of Greece, the Corinthians treated Roman senatorial ambassadors with

disrespectful violence. After the short war which followed, the Roman consul

Lucius Mummius razed Corinth and enslaved its inhabitants. Mummius was hardly a

philhellene. For Greek art treasures, he displayed the enthusiasm of a

collector rather than a connoisseur.

The same year (146 BC) had seen the destruction of Carthage,

bringing the Third and last Punic War to its bitter end. The Carthaginians had

recalled from exile an able general – another Hasdrubal – who organized their

very solid defences. Against the 45-foot (13.7m) city walls, the Romans made

slow progress. The Roman besieging army itself, at one time in grave danger,

was saved only by the energy and resource of Scipio Aemilianus, son of Aemilius

Paullus, victor of Pydna, and grandson by adoption of the Scipio Africanus who

had defeated Hannibal.

When the Carthaginians were successful in running the Roman

blockade by sea, Scipio built a mole across the gulf into which their harbour

issued, thus cutting them off. The Carthaginians dug a canal from their inner

(naval) harbour basin to the coast and put to sea with a full fleet, but the

Romans defeated them in a naval engagement. The walls of Carthage were finally

breached, Hasdrubal surrendered and was reserved for the day when Scipio

triumphed as a victorious general in Rome, but his wife and children preferred

to perish in the flames which enveloped the Carthaginians citadel and temples.

Another appalling siege was that of Numantia in 133 BC. For

Rome, the capture of Numantia marked the successful culmination of a savage and

often shameful war in which, after the elimination of Carthage, the Romans aimed

to impose their rule on the native peoples of the Spanish peninsula. The siege

operations at Numantia were, like those at Carthage, conducted by Scipio

Aemilianus.

Scipio was something of an expert in sieges. Appian says

that he was the first general to enclose with a wall an enemy who was prepared

to give battle in the open field. It might have been expected that such an

enemy would prove impossible to contain. But Scipio’s measures were very

thorough.

Numantia was beset with seven forts and surrounded by a

ditch and palisade. The perimeter of the circumvallations was twice as long as

that of the city. At the first sign of a sally by the defenders, the threatened

Roman sector had orders to hoist a red flag by day or raise a fire signal by

night, so that reinforcements could immediately be rushed to the danger spot.

Another ditch was built behind the first, also with palisades, after which a

wall 8 feet (2.4m) high and 10 feet (3m) wide (not including parapets) was

constructed. Towers were sited at 100-foot (30.5m) intervals along the wall,

and where the wall could not be carried round the adjacent marshland its place

was taken by an earthwork of the same height, thicker than the wall.

The river Durius (Duoro), on which Numantia stood, enabled

the defenders to be supplied by means of small boats, swimmers and divers.

Scipio therefore placed a tower on either side of the river, to which he moored

a boom of floating timbers. The timbers bristled with inset knives and

spearheads and were kept in constant motion by the strength of the current.

They acted as a barrage, effectively isolating the city from any help which

might reach it along the river.

Catapults and all kinds of siege engines were now mounted on

Scipio’s towers and missiles were accumulated along the parapets, the forts

being occupied by archers and slingers. Messengers were stationed at frequent

intervals along the entire wall in order that headquarters might be informed

immediately of any enemy action, whether by day or night. Each tower was furnished

with emergency signals and each was ready to send immediate help to another in

case of need.

Thus invested for eight months, the Numantines starved. They

took to cannibalism, and at last 4,000 surviving citizens, now mere filthy and

ragged skeletons, surrendered unconditionally.

■

Roman Camps

Excavations at Numantia have brought to light 13 Roman camps

in the vicinity. Seven of these have been identified as Scipio’s. Others were

those of his less successful predecessors in Spain. The Numantine excavations

of Schulten testify in general to the accuracy of Polybius’ description of

Roman camps, though some notable differences in internal arrangements and

dimensions must be recognized.

A camp containing two legions with an equivalent strength of

Italian allied contingents, commanded by a consular general, was normally built

in the form of a square. A main road (via principalis), 100 feet (30.5m) wide,

separated the headquarters of the general, with those of his paymaster

(quaestor)3, staff of officers and headquarters troops, from those of the

legionaries and attached cavalry. The via principalis issued on either side

through gates in the camp wall. The headquarter section of the camp covered one-third

of its total area. The remaining two-thirds was itself bisected by another road

(via quintana), 50 feet (15.2m) wide, parallel to the main road. The word

quintana indicated that it was adjacent to the tents of the fifth maniple and

its attached cavalry. Both these roads were bisected at right angles by a third

road, which ran to the general’s headquarters from a gate in the farthest wall.

The headquarters (praetorium) was connected by a short road, on the other side,

to a gate in the nearer wall.

Between the camp ramparts and the tents inside, a margin

(intervallum) of 200 feet (6lm) was left vacant. This placed the tents out of

reach of enemy missiles – especially fire darts. In exceptional cases, also,

the camp could accommodate extra troops, and there was room to stow booty.

Before the battle of the Metaurus, Claudius Nero had managed to smuggle his own

legions into the camp of his colleague Livius without the enemy being aware of

it. Hasdrubal only knew that he faced two consular armies instead of one when

he heard the same trumpet call sounded twice in the same camp.

A Roman army never halted for a night without digging itself

a camp. The perimeter was formed by a ditch, normally about 3 feet (.91m) and 4

feet (1.22m) wide. The excavated earth was flung inside to form a rampart,

which was surmounted by a breastwork of sharpened stakes. For the purpose of

constructing such a camp, each soldier on the march carried a spade, other

tools and sharp stakes to set in the rampart.

In wartime, a Roman army encamped at a chosen spot for the

winter. In this case, the camp comprised a more solid structure. The tents made

of skin were replaced by huts thatched with straw. Each tent or hut held eight

men, who messed together. Polybius’ account suggests that the huts or tents

were laid out in long lines with streets between them, but the evidence of

Numantia excavations points to the grouping of maniples round a square.

■ The

Military Achievement of Marius

In the days when Marius had first served in North Africa,

the nobiles were once more in precarious control of Roman politics. They were

at least sufficiently in control to mismanage foreign wars. When Marius, a

member of the equestrian class, declared his intention of standing for the

consulate, his aristocratic commanding officer insulted him. However, Marius

possessed ability, energy, wealth, influential family connections and a flair

for intrigue. He became consul in 107 BC and superseded the general who had

slighted him. However, no amount of intrigue could have raised Marius to the

eminence for which he was destined if events had not conspired to demonstrate

his very real military ability, both in the Jugurthine War and the campaigns

against the barbarians.

A land-hungry Germanic tribe, the Cimbri, had left their homes

in Jutland and together with other tribes, including the Teutones, whose name

is remembered above all in this connection, had migrated southwards, carrying

with them their entire families and moveable possessions. The Romans were

alarmed and a consular army met the migrants in Noricum, a Celto-Illyrian area

north-east of the Alps. In the ensuing battle the Romans were badly defeated.

The Cimbri and their allies must have found that the Alps presented a more

formidable barrier than the Rhône and they fortunately avoided Italy, moving

westward into Gaul (Southern France), an area which was by now under Roman

control. Several Roman armies attempted to eliminate the barbarian menace, but

they met with a series of humiliating defeats culminating in a major disaster

at Arausio (Orange) in 105 BC, which much disturbed Rome.

The campaigns against the migrants could be regarded as

offensive wars. The German tribes were fighting in defence of the families they

had with them, and the Romans had rigidly, though not unwisely, refused to

negotiate or concede any right of settlement to the barbarians. After Arausio,

however, the way to Italy lay open to the Germanic invaders and Rome was

unquestionably on the defensive. A full state of emergency existed and in these

circumstances Marius, who had recently emerged as conqueror of Jugurtha, was

elected consul for the second and successive year (105 BC). Legally, ten years

should have elapsed before his second election. Constitutional precedent

required that the consul should be sponsored by the Senate. But the Popular

Assembly, as the legislative body of the Republic, was free to do as it chose.

In any case, the Romans rarely insisted on constitutional niceties where they

conflicted with military expediency.

Marius gloriously justified his appointment. Fortunately,

the Germans had not immediately attempted the invasion of Italy but moved

westwards towards Spain. This gave Marius time to train his troops for the

coming conflict. Much of his success may be attributed to good military

discipline and administration. He was appointed consul for the third time

before he came to grips with the enemy. He even had leisure to improve his

supply lines by setting his men to dig a new channel at the mouth of the Rhône.

The Teutones and the Ambrones (another allied German tribe)

parted company from the Cimbri and the Tigurini (a Celtic people who had joined

them). While the former confronted Marius on the Rhône, the latter made for

Italy by a circuitous march over the Alps. Marius restrained his men in their

camp to allow them to become accustomed to the sight of the barbarians who

surrounded them, calculating that familiarity would breed contempt. When the

Teutones marched on towards Italy, bypassing his camp, he led his own men out

and overtook the enemy near Aquae Sextiae (Aix-en-Provence). Here, he fought a

battle on favourable ground and, making use of a cavalry ambush posted in the

hills, completely annihilated the Teutones. Their allies, the Ambrones had

already been slaughtered in great numbers in a fight at a watering place two

days earlier.

Marius’ consular colleague in North Italy fared by no means

so happily and was forced to withdraw before the invading Cimbri into the Po

valley, leaving them to occupy a large part of the country. In 101 BC, Marius’

legions were brought to reinforce the north Italian army, Marius being now in

his fifth consulate. A battle was fought at Vercellae (perhaps near Rivigo).

The barbarians’ tactics were not utterly devoid of sophistication and had some

success. Nor were the Germans ill-armed. Their cavalry wore lofty plumes on

helmets grotesquely shaped like animal heads. Their breastplates were of iron

and they carried flashing white shields, two javelins each and heavy swords for

hand-to-hand fighting. The summer heat may have been in favour of the Romans,

who were accustomed to the Mediterranean climate. Fighting was confused on

account of a heavy dust storm. The Roman victory may be ascribed to superior

training and discipline. Sulla, on whose account Plutarch relies, suggested

that Marius’ tactics were mainly designed to secure glory for himself at the

expense of his consular colleague. Sulla himself fought in the battle, but one

would not expect his evidence to be unbiased. In any case, the entire Germanic

horde was destroyed and Rome was spared a catastrophe that might have proved

conclusive to its political existence. For unlike the victors of the Allia,

three centuries earlier, the Cimbri were in search of land, not gold. The greatest

threat presented by the northern barbarians lay in their numbers, estimated at

a total of 300,000; some ancient historians thought that this was an

underestimate. The Romans at Vercellae were a little more than 50,000 strong.

At the same time, the barbarians’ great trek southward from Jutland, let alone

their subsequent victories over Roman armies, cannot have been achieved without

leadership. It is surprising that the names of the Germanic leaders are not at

least as celebrated as that of Brennus.

■ Recruitments

The wars against the Cimbri and the Teutones are poorly

documented. Marius emerges as both strategist and tactician, a leader

possessing formidable discipline and great physical courage. Yet the secret of

his success may well have lain in his ability as a military administrator and

the intelligence of his military reforms.

One has only to consider his methods of recruitment.

Constitutionally, these were outrageous and exposed him to the ever-increasing

hostility of the Senate. But from a social and strategic point of view, they

were precisely what Rome needed. Since the time of the Servian reforms, the poorest

section of the population (proletarii) had not qualified for enrolment in the

legions, except in times of grave national emergency. The name proletarii in

fact signifies those who contributed only their children (proles) to the

community – not their taxes or their military service. Plutarch suggests that

only propertied classes were required in the army, since their possessions were

some sort of a security for their good behaviour. In any case, it must have

been felt that they had a greater stake in the society they defended.

At the time when Marius had been appointed by ‘the People’

to his first term as consul, Roman citizens were undergoing a process of

proletarianization. The land, from which the farmer was being forced by low

overseas corn prices, was brought up by wealthy absentee landlords, who were

able to run their estates with the help of cheap labour, supplied by a

multitude of enslaved war captives. Meanwhile, the small farmer moved into the

city, where he could at least take advantage of the cheap and subsidized corn

which often proved to be the price of his political support.

The Senate had ruled that extra levies should be raised for

the Jugurthine War. Marius, finding the measure inadequate, and always ready to

provoke the Senate, recruited not only volunteers and time-expired veterans –

which it was open to him to do – but also offered enlistment to members of the

proletariat who wished to go soldiering. Whereas previously the field for

recruitment had been progressively narrowing as property requirements became

harder to satisfy, Marius raised a strong army and at the same time produced

one remedy for the problem of unemployment.

As long as he enjoyed the support of the People’s Assembly

and its tribunes, the Senate could not check Marius’ recruiting activities. His

methods, however, had an ominous aspect. Roman soldiers, though now members of

a fully professional army, owed personal loyalty to the general who enrolled

and employed them. This loyalty was enhanced by traditional Roman concepts of

the semi-sacred relationship which existed between a protector (patronus) and

his protégé (cliens): a relationship which in some contexts acquired legal

definition. Marius became a patron to his veteran soldiers, securing for them,

through his political associates, a grant of farmland on retirement. The day of

private armies, when soldiers owed prime allegiance to their generals rather

than to the state, was not far off.

■

Army Reorganization

At the battle of Aquae Sextiae, Marius gave the order to his

men, through the usual chain of command, that they should hurl their javelins

as soon as the enemy came within range, then use their swords and shields to

thrust the attackers backwards, down the treacherous slope. The instructions to

discharge javelins and then join battle with swords and shields is such as we

might expect to be given to an army which had adopted the pilum and the

gladius, but the offensive use of shields and the application of pushing

tactics sounds like a reversion to the old fifth- and fourth-century phalanx as

it had been used both in Greece and Italy. The probability is that the

traditional manipular formation with its three-line quincunx deployment had generally

been superseded. In the course of the preceding century, Rome had come into

conflict with a wide assortment of enemies, variously equipped and accustomed,

and the Romans were nothing if not adaptable. They were ready to improve and to

adopt such tactics as suited the terrain and were most likely to prove

effective against the type of enemy with whom they had to deal in any

particular battle. There were no longer any routine tactics. The maniple which

had been the unit of the old three-line battle front was in the first place a

tactical unit (see here). Once it had ceased to be tactically effective, there

was no reason for its retention. Marius recognized this fact and reorganized

his army accordingly.

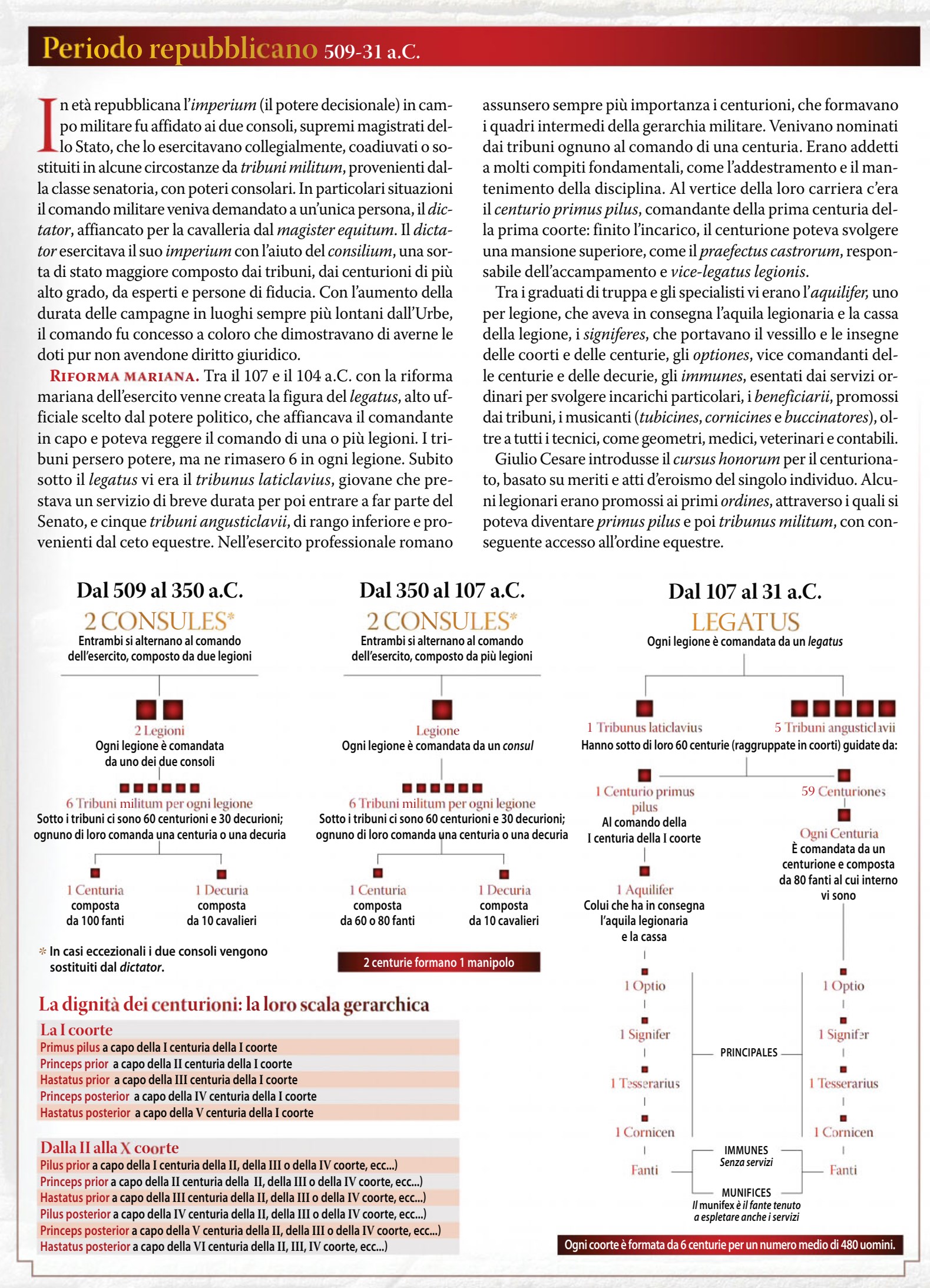

For purposes of administration a larger unit than the

maniple was convenient; and in this, subdivisions were necessary. The legion

was consequently divided into ten cohorts, and every cohort contained six

centuries, each commanded by a centurion, whose titles, ranging from that of

the exalted primus pilus to hastatus posterior, reflected differences of

position on the battlefield, rank and seniority. Before Marius’ time, the

cohort, notably as used by Scipio in Spain (134 BC), was often a purely

tactical formation, employed to cope with special circumstances. On the other

hand, it had originated as an administrative infantry unit among the Italian

allies. Cohorts had been mobilized originally as 500 and 1,000 strong

respectively. Each had been under the command of a praefectus. As a legionary

unit, the cohort was 500–600 strong. Its division into six centuries meant that

these were each somewhat under 100 strong, larger than the old manipular

centuries, which had sometimes contained as few as 60 men.

Marius abolished the velites, the skirmishers of the ancient

Camillan army; and with them, their characteristic arms of light spear and

small buckler (parma) disappeared. The pilum was now used by all legionaries,

and Marius introduced a change in its manufacture. In place of one of the iron

rivets which had secured the head to the shaft, he had a wooden peg inserted.

When the javelin impaled an enemy shield, the peg broke on impact and the shaft

sagged and trailed on the ground, though still attached to the head by the

remaining iron rivet. Not only was the javelin thus rendered unserviceable to

enemy hands, but it encumbered the warrior whose shield it had transfixed.

According to Plutarch, this novelty was introduced in preparation for the

battle with the Cimbri at the battle of Vercellae. At the later date, in Julius

Caesar’s army, as a further refinement, the long shank of the pilum was made of

soft iron, so that it bent even while it penetrated.

Marius was at pains to be sure that every soldier in his

army should be fit and self-reliant. He accustomed his men to long route

marches and to frequent moves at the double. In addition to their arms and

trenching tools, he insisted on their carrying their own cooking utensils and

required that every man should be able to prepare his own meals. Flavius

Josephus, the Jewish historian who wrote in the first century AD, describes the

legionary as carrying a saw, a basket, a bucket, a hatchet, a leather strap, a

sickle, a chain and rations for three days, as well as other equipment. If this

was a legacy for Marius’ reforms, it is easy to understand why the men who

patiently supported such burdens were nicknamed “Marius’ mules”. Campaigning in

enemy country or where there was a danger of sudden attack, the Romans marched

lightly equipped and ready for action at short notice, while the soldiers’

packs (sarcinae) were carried with the baggage train. Marius is also said to

have introduced a quick-release system for the pack.