Rome now dominated southern and central Italy, including

Etruria and the Greek cities. Northern Italy, of course, remained largely

occupied by the Gauls, and the Gauls remained a menace. The process by which

Rome had developed from a small military outpost on a river-crossing to become

the dominant power of the Italian peninsula had been by no means swift or

continuous. It had taken the greater part of five centuries, and during that

time Rome itself had twice been occupied by a foreign power.

According to traditional stories, the last of Rome’s kings,

Tarquinius Superbus, an Etruscan, had been expelled late in the sixth century

BC after his son had villainously raped the wife of a noble kinsman. Etruscan

armies under Lars Porsenna had attempted to restore Tarquinius but had been

thwarted by the heroism of Horatius who, with two comrades, defended the Tiber

crossing against them until the demolition of the bridge was completed. The

Latin cities to the south had then combined to replace the exiled monarch on his

throne, but had been defeated by the Romans at the battle of Lake Regillus

(where the Romans were assisted by the gods according to the legend!).

Illustrated Etruscan tomb inscriptions, taken in conjunction

with the existing legends, suggest that the underlying historical facts were

very different. It is clear that Porsenna was not the friend but the mortal

enemy of Tarquinius, his fellow Etruscan. He probably conspired with

aristocratic, partly Etruscan elements in Rome to precipitate Tarquinius’

downfall, and then himself occupied Rome. He certainly advanced south of Rome,

to fight the Latins and their Greek allies of Cumae – where according to one

story Tarquinius ultimately took refuge. When the Etruscans were defeated by

the Latin League at Aricia (as described by Livy), their fugitives were

received and protected in Rome. Moreover, Livy stresses the friendship of

Porsenna towards the Romans and his chivalrous respect for their way of life.

One would guess that Rome had accepted the position of subject ally to Etruria.

The Roman population, despite its Etruscan overlordship, was of course Latin;

their Etruscan allegiances brought them into conflict with the other Latin

cities, who were allied to the Greek maritime states – Etruria’s commercial

rivals.

At Rome, Latin patriotic sentiment may have accepted

Etruscan kings and welcomed their leadership against Etruria itself, just as

English patriotic feeling in the Middle Ages accepted French-speaking

Plantagenet kings as leaders against the French. The early Roman historians,

however, did not like to contemplate their city as a mere catspaw in Etruscan

dynastic politics, let alone a puppet state to be employed against their Latin

brothers. Consequently, these chroniclers substituted history of their own invention,

assigning fictional roles to historic characters.

As the strength of Etruria diminished, Rome asserted its

authority over both the Etruscans and the Latins, but at the beginning of the

fourth century BC the city was overwhelmed, after the disastrous battle of the

Allia, by a vast horde of Gallic raiders. The Romans retreated into their

citadel on the Capitoline Mount; they eventually bought off the Gauls, whose

immediate interest was in moveables and not in land. Roman history records that

the great Camillus, Rome’s exiled war leader, was recalled to speed the parting

Gauls with military action, but this thinly veils the fact that the Gauls

departed of their own accord, having obtained what they wanted. Livy blames

Roman decadence and impiety for the disaster, but the Romans must in any case

have been vanquished by sheer weight of numbers. Apart from that, they were

never at their best when dealing with a strange foe whose weapons and methods

of warfare were new to them.

Roman military history is chequered by catastrophes. Few

great empires can have sustained more major disasters during the period of

their growth. Nobody would deny that the Romans were a formidable military

nation; yet the genius which enabled them eventually to dominate the ancient world

was as much political as military. Their great political instrument was their

concept of citizenship. Citizenship was not simply a status which one did or did

not possess. It was an aggregate of rights, duties and honours, which could be

acquired separately and conferred by instalments. Such were the rights of

making legal contracts and marriages. From both of these the right to a

political vote was again separable; nor did the right to vote necessarily imply

the right to hold office. Conquered enemies were thus often reconciled by a

grant of partial citizenship, with the possibility of more to come if behaviour

justified it. Some cities enjoyed Roman citizenship without the vote, being

autonomous except in matters of foreign policy. Even the citizens of such

communities, however, might qualify for full Roman citizenship if they migrated

to Rome; where this right was not available, citizenship could be obtained by

those who achieved public distinction in their own communities.

■ The

Roman Army in Early Times

Citizenship, of course, implied a military as well as a

political status. For the duties which it imposed were, above all, military.

The Latin and other Italian allies, who enjoyed some intermediate degree of

citizenship, were in principle required to supply an aggregate of fighting men

equal to that levied by the Romans themselves. In practice, the Romans relied

on their Italian allies particularly for cavalry: an arm in which they

themselves were notoriously weak. The Greek cities did not normally contribute

military contingents, but supplied ships and rowers. They were known as “naval

allies” (socii navales) because of this function.

Any army whose technical resources are comprised by

hand-arms, armour and horses, will, at all events in the early years of its

development, reflect an underlying social order. Combatants who can afford

horses and armour will naturally be drawn from the aristocracy. Others will

have little armour and less sophisticated, if not fewer, weapons. This was true

of Greek armies and also of medieval armies. It was certainly true of the

Romans, whose military class differentiation was defined with unusual care and

with great attention to detail. The resulting classification is associated with

the military and administrative reorganization of Servius Tullius,

traditionally sixth and penultimate king of Rome. His name suggests a

sixth-century date for the reforms in question, though some scholars think that

the so-called Servian organization was introduced later than this.

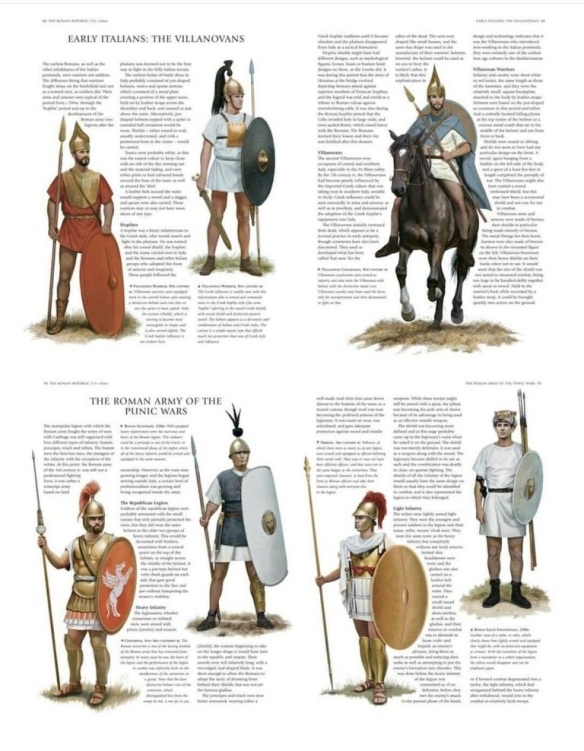

The “Servian” infantry was divided into five property

classes, the wealthiest of which was armed with swords and spears and protected

by helmets, round shields, greaves and breastplates. All protective armour was

of bronze. In the second class, no breastplate was worn, but a long shield was

substituted for the round buckler. The third class was as the second, but wore

no greaves. The fourth class was equipped only with spears and javelins; the

fifth was composed of slingers. There is no reference to archers. The poorest

citizens were not expected to serve except in times of emergency, when they

were equipped by the state. However, they normally supplied artisans to

maintain siege engines and perform similar duties.

The army was also divided into centuries (i.e., “hundreds”),

as the citizens were for voting purposes. However, a century soon came to

contain 60, not 100 men. The first property class comprised 80 centuries; the

second, third and fourth class had 20 centuries apiece; the fifth class had 30.

A distinction was made between junior and senior centuries, the former

containing young men for front-line action, the latter older men, more suitable

for garrison duty. A single property class was equally divided between the two

age groups.

The cavalry was recruited from the wealthiest families to

form 18 centuries. A cavalry century received a grant for the purchase of its

horses and one-fifth of this amount yearly for their upkeep. The yearly grant

was apparently provided by a levy on spinsters! In general, the financial burden

of warfare was shifted from the poor on to the rich. For this imposition, the

rich were compensated by what amounted to a monopoly of the political suffrage.

Inevitably, it was felt in time that they were overcompensated, but that is a

matter which must not detain us here.

During the early epochs of Roman history, as archaeological

evidence indicates, Greek hoplite armour was widely imitated throughout the

Mediterranean area. Italy was no exception to this rule and, as Livy’s

description suggests, Rome was no exception in Italy. Greek weapons called for

Greek skill in their use, and this in turn assumed Greek tactical methods. The

Romans were in contact with Greek practice, both through their Etruscan

northern neighbours, who as a maritime people were more susceptible to overseas

influences, and through direct contact with Greek cities in Italy, notably

Cumae. The Roman army, as recruited on the Servian basis, must have fought as a

hoplite phalanx, in a compact mass, several ranks deep, using their weight

behind their shields as well as their long thrusting spears. The light troops

afforded by the fourth and fifth infantry classes will have provided a

skirmishing arm, and the cavalry held the wings on either side of the phalanx.

There were also two centuries of artificers (fabri) attached to the centuries

of the first class, and two of musicians (made up of hornblowers and

trumpeters).

■ The

Military Reforms of Camillus

The next great landmark in Roman military organization is

associated with the achievements of Camillus. Camillus, credited with having

saved Rome from the Gauls and remembered as a “second founder” of Rome, was a

revered national hero. His name became a legend, and legends accumulated round

it. At the same time, he was unquestionably a historical character. We need not

believe that his timely return to Rome during the Gallic occupation deprived

the Gauls of their indemnity money, which was at that very moment being weighed

out in gold. But his capture of the Etruscan city of Veii is historical, and he

may here have made use of mining operations such as Livy describes. Similarly,

the military changes attributed to him may in part, if not entirety, be due to

his initiative.

Soon after the withdrawal of the Gauls from Rome, the

tactical formation adopted by the Roman army underwent a radical change. In the

Servian army, the smallest unit had been the century. It was an administrative

rather than a tactical unit, based on political and economic rather than

military considerations. The largest unit was the legion of about 4,000

infantrymen. There were 60 centuries in a legion and, from the time of

Camillus, these centuries were combined in couples, each couple being known as

a maniple (manipulus). The maniple was a tactical unit. Under the new system,

the Roman army was drawn up for battle in three lines, one behind the other.

The maniples of each line were stationed at intervals. If the front line was

forced to retreat, or if its maniples were threatened with encirclement, they

could fall back into the intervals in the line immediately to their rear. In

the same way, the rear lines could easily advance, when necessary, to support

those in front. The positions of the middle-line maniples corresponded to

intervals in the front and rear lines, thus producing a series of quincunx

formations. The two constituent centuries of a maniple were each commanded by a

centurion, known respectively as the forward (prior) and rear (posterior)

centurion. These titles may have been dictated by later tactical developments,

or they may simply have marked a difference of rank between the two officers.

The three battle lines of Camillus’ army were termed, in

order from front to rear, hastati, principes and triarii. Hastati meant

“spearmen”; principes, “leaders”; and triarii, the only term which was

consistent with known practice, meant simply “third-liners”. In historical

accounts, the hastati were not armed with spears and the principes were not the

leading rank, since the hastati were in front of them. The names obviously

reflect the usage of an earlier date. In the fourth century BC the two front

ranks carried heavy javelins, which they discharged at the enemy on joining

battle. After this, fighting was carried on with swords. The triarii alone

retained the old thrusting spear (hasta). The heavy javelin of the hastati and

principes was the pilum. It comprised a wooden shaft, about 4.5 feet (1.4m)

long, and a lancelike, iron head of about the same length as the shaft; which

fitted into the wood so far as to give an overall length of something less than

7 feet (2.1m). The Romans may have copied the pilum from their Etruscan or

Samnite enemies; or they may have developed it from a more primitive weapon of

their own. The sword used was the gladius, a short cut-and-thrust type, probably

forged on Spanish models. A large oval shield (scutum), about 4 feet (1.2m)

long, was in general use in the maniple formation. It was made of hide on a

wooden base, with iron rim and boss.

It has been suggested that the new tactical formation was closely

connected with the introduction of the new weapons. The fact that the front

rank was called hastati seems to indicate that the hasta, or thrusting spear,

was not abandoned until after the new formation had been adopted. Indeed, cause

and effect may have stood in circular relationship. The open formation could

have favoured new weapons which, once widely adopted, forbade the use of any

other formation. At all events, there must have been more elbow room for aiming

a javelin.

Apart from these considerations, open-order fighting was

characteristic of Greek fourth-century warfare. Xenophon’s men had opened ranks

to let the enemy’s scythe-wheel chariots pass harmlessly through. Agesilaus

used similar tactics at Coronea. Camillus was aware of the Greek world – and

the Greek world was aware of him. He dedicated a golden bowl to Apollo at

Delphi and Greek fourth-century writers refer to him. It is at least possible

that the new Roman tactical formation was based on Greek precedents, as the old

one had been.

■

Officers and Other Ranks

The epoch of Camillus also saw the first regular payments

for military service. The amount of pay, at the time of its introduction, is

not recorded. To judge from the enthusiasm to which it gave rise and to the

difficulty experienced in levying taxes to provide for it, the sum was

substantial. It was a first step towards removing the differences among

property classes and standardizing the equipment of the legionary soldier. For

tactical purposes, of course, some differences were bound to exist: for

instance, in the lighter equipment of the velites. But the removal of the

property classes produced an essential change in the Roman army, such as the

Greek citizen army had never known. The Athenian hoplites had always remained a

social class, and hoplite warfare was their distinctive function. The Spartan

hoplites had been an élite of peers, every one of them, as Thucydides remarks,

in effect an officer.

At Rome, however, the centuries of which the legions were

composed were conspicuously and efficiently led by centurions, men who

commanded as a result of their proven merit. The Roman army, in fact, developed

a system of leadership such as is familiar today – a system of officers and

other ranks. Centurions were comparable to warrant officers, promoted for their

performance on the field and in the camp. The military tribunes, like their

commanding officers, the consuls and praetors, were at any rate originally

appointed to carry out the policies of the Roman state, and they were usually

drawn from the upper, politically influential classes.

Six military tribunes were chosen for each legion, and the

choice was at first always made by a consul or praetor, who in normal times

would have commanded two out of the four legions levied; as colleagues, the

consuls shared the army between them. Later, the appointment of 24 military

tribunes for the levy of four legions was made not by the consuls but by an

assembly of the people. If, however, additional legions were levied, then the

tribunes appointed to them were consular nominations. Tribunes appointed by the

people held office for one year. Those nominated by a military commander

retained their appointment for as long as he did.

Military tribunes were at first senior officers and were

required to have several years of military experience prior to appointment. In

practice, however, they were often young men, whose very age often precluded

them from having had such experience. They were appointed because they came

from rich and influential families and they thus had much in common with the

subalterns of fashionable regiments in latter-day armies. Originally, an

important part of the military tribune’s duties had been in connection with the

levy of troops. In normal times, a levy was held once a year. Recruits were

required to assemble by tribes (a local as distinct from a class division). The

distribution of recruits among the four legions was based on the selection made

by the tribunes.

“Praetor” was the title originally conferred on each of the

two magistrates who shared supreme authority after the period of the kings. The

military functions of the praetor are well attested, and the headquarters in a

Roman camp continued to be termed the “praetorium”. In comparatively early

times, the title of “consul” replaced that of “praetor”, but partly as a result

of political manoeuvre, the office of praetor was later revived to supplement

consular power. The authority of a praetor was not equal to that of a consul,

but he might still command an army in the field.

The command was not always happily shared between two

consuls. In times of emergency – and Rome’s early history consisted largely of

emergencies – a single dictator with supreme power was appointed for a maximum

term of six months, the length of a campaigning season. The dictator chose his

own deputy, who was then known as the Master of the Horse (magister equitum).

The allies, who were called upon to aid Rome in case of war,

were commanded by prefects (praefecti), who were Roman officers. The 300

cavalry attached to each legion were, in the third century BC at any rate,

divided into ten squadrons (turmae), and subdivided into decuriae, each of

which was commanded by a decurio, whose authority corresponded to that of a

centurion in the infantry.