Known popularly as PT boats, World War II–era patrol-torpedo

boats were the American equivalent of German E boats and British motor torpedo

boats. They were small, fast, wooden-hulled, shallow-draft vessels that

depended on surprise, speed, and maneuverability and thus did their best work

in coastal waters.

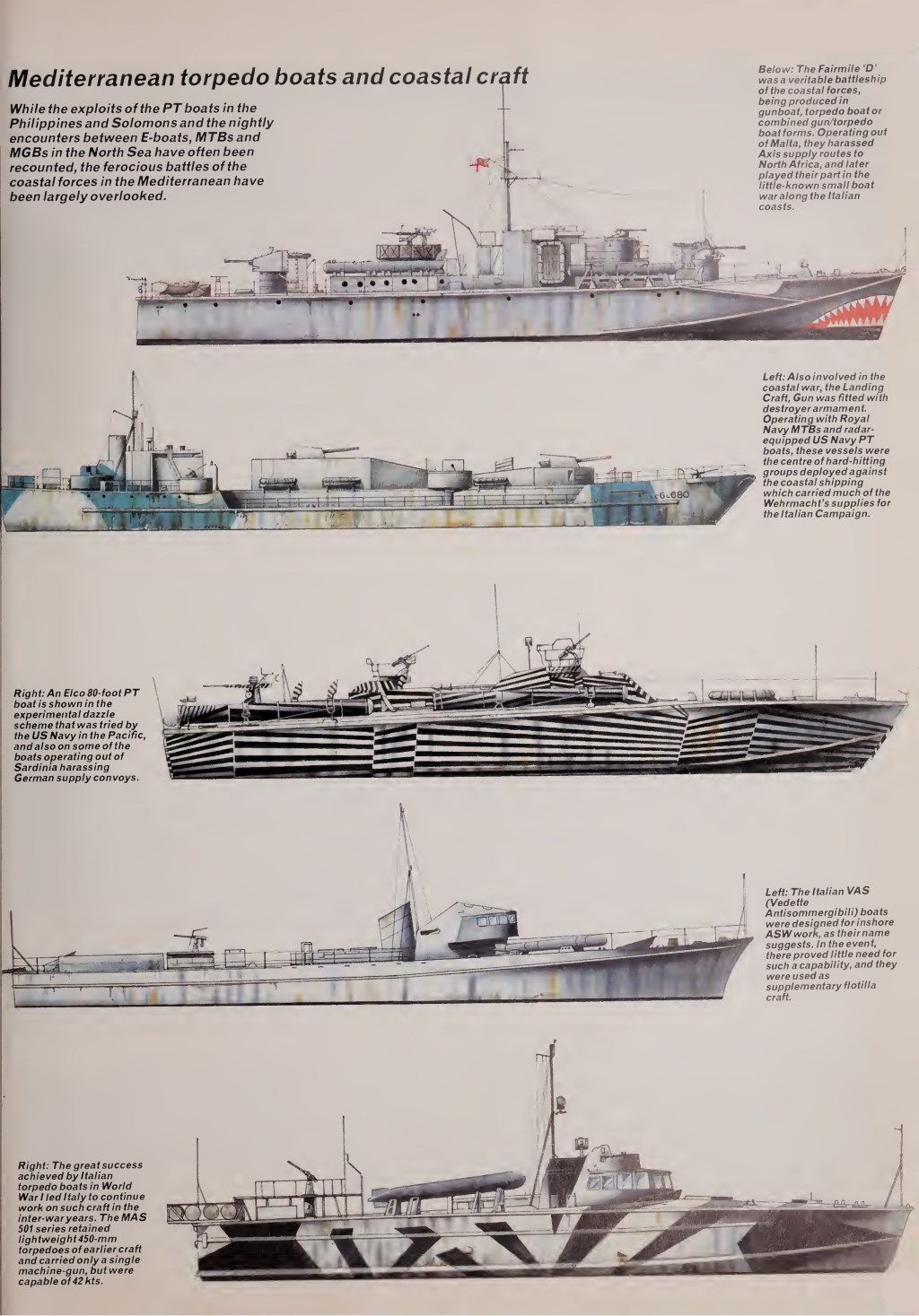

During World War I, the Italian navy built and used some 299

torpedo-armed motorboats against the Austro- Hungarian navy in the Adriatic.

From 1916, the British navy used coastal motor boats in home waters and in the

raids against Ostend and Zeebrugge, Belgium, in April 1918. Although the United

States did not use such craft in World War I, the Electric Boat Company’s Elco

Division in Bayonne, New Jersey, constructed several hundred power boats for

Britain and Italy and gained expertise in designing and manufacturing that type

of vessel.

In the late 1930s, the U.S. Navy was pushed toward the

development of gasoline-powered motor boats by President Franklin D. Roosevelt

and Assistant Secretary of the Navy Charles Edison, both of whom were concerned

about European interest in these craft. They secured a 1938 appropriation of $5

million for the construction of ships of fewer than 3,000 tons displacement. In

June, the navy staged an American design competition, selecting seven winners

for further testing, but Edison decided instead to put into limited production

at Elco a 70 ft craft, with a crew of 10 men, from the British designer Hubert

Scott- Paine. Elco’s boat substituted Packard engines for those of Rolls-Royce.

By 1941, Elco had progressed to a 77 ft version that demonstrated an average

speed of 27.5 knots in rough waters and mounted 2 ÷ 21-in. torpedo tubes and 2

÷ 50-caliber machine guns in twin turrets. The boats also had the ability to

lay smokescreens. Andrew Jackson Higgins, a Louisiana shipbuilder, developed a

similar 78 ft vessel. At 80 ft or less, the boats could be carried on long

voyages by larger ships.

During World War II, the United States deployed in the

Pacific 350 PT boats, mostly of the Elco and Higgins types, along with 42 in

the Mediterranean and 33 in the English Channel. Together, they launched in

combat a total of only 697 torpedoes, usually with minimal success. All too

often, American torpedoes were defective, and firing them accurately from

fast-moving vessels was problematic in any case. Nor were PT boats fortunate at

antisubmarine warfare, being much too noisy to make effective use of sonar

equipment. The most memorable action in European waters by this type of craft

came from the Germans when they sent their E boats in an attack on an American

landing exercise at Slapton Sands, England, on 18 April 1944. The Germans sank

two LSTs (landing ships, tank), damaged a third, and killed more than 700

Americans.

1943 – German Schnellboot S.100.

German S-boats of World War II were among the best small combatant

vessels ever produced. The armament carried by the S-boats gave them

almost the same firepower as that of a destroyer and specially developed

paint schemes rendered them almost impossible to see at night. The

S-boat had a cruising range of 700-750 miles with speeds from 39-43.5

knots.

S-boats were often used to patrol the Baltic Sea and the

English Channel in order to intercept shipping heading for the English ports in

the south and east. As such, they were up against Royal Navy and Commonwealth

(particularly Royal Canadian Navy contingents leading up to D-Day) Motor Gun

Boats (MGBs), Motor Torpedo Boats (MTBs), Motor Launches, frigates and

destroyers. They were also transferred in small numbers to the Mediterranean,

and the Black Sea by river and land transport. Some small S-boats were built as

boats for carrying by auxiliary cruisers.

Crew members could earn an award particular to their

work—Das Schnellbootkriegsabzeichen—denoted by a badge depicting an S-boat

passing through a wreath. The criteria were good conduct, distinction in

action, and participating in at least twelve enemy actions. It was also awarded

for particularly successful missions, displays of leadership or being killed in

action. It could be awarded under special circumstances, such as when another

decoration was not suitable.

Although the development of the automotive torpedo in the

late 19th century promised to realize the dream of the small warship with the

killer punch, the need for this ‘torpedo boat’ to work with and against fleets

at sea stimulated too large an increase in size, a trend aggravated by the

contemporary technology of steam machinery in displacement hulls. The

development of the fast planing hull and the internal combustion engine began

the cycle afresh, with progress before 1914 owing much to the commercial

prospects of high-speed boating. It was but a small step to mount torpedoes on

such craft, and the same specialist yards have tended to remain in the business

to this day.

Much effort was put into the production of torpedo-carrying

coastal craft during World War l, but only the Italians in the Adriatic and the

British in the English Channel and the Baltic ever demonstrated their true

potential. Neither employed massed attack, preferring to work singly or in

small groups to capitalize on the advantages of agility, surprise and good

planning. The Italians were particularly imaginative, evolving craft and

tactics to assault an Austro-Hungarian fleet snug in well-defended harbours.

The British had to contend with poorer weather conditions and soon learned the

value of larger and stronger hulls. They also discovered the threat posed by

aircraft and fire from ashore, suffering losses from both despite small size

and manoeuvrability. Experience did not turn the British away from hard-chine

designs; they accepted a drop in performance in heavy weather in exchange for

the benefit of really high speed in calmer water.

After World War I the British totally lost interest in

coastal craft, being occupied with deep-sea imperial matters. The Italians went

on initially to be joint front runners with the Germans, who saw in the

small-torpedo boat a means of constructing useful naval tonnage outside treaty

restrictions. Beneath the lax gaze of the regulating authorities they built and

evaluated numerous hulls under sporting-club colours and, over a decade,

identified what were to be the major S-boat characteristics: displacement hull,

wood on light alloy construction, stability reserves for 533-mm (21-in)

torpedoes and, finally, the small marine diesel. This type of engine required

careful development and, once perfected, remained peculiar to German practice,

with foreign navies never producing a satisfactory competitor despite the fire

risks associated with petrol engines, for which they treated effect rather than

cause by introducing self-sealing tanks and improved fire-extinguishing

systems.

The Italian lsotta-Fraschini was an excellent petrol engine,

used widely abroad until 1940; it was probably its very availability that

inhibited comparable development elsewhere. During World War I the Italians

found the small planing hull adequate for their Adriatic operations. Translated

into the open-sea war of 1940-3 it proved unsatisfactory and was dropped in

favour of a German type of round-bilge form.

A considerable increase in efficiency resulted in the

abandoning of direct-drive for purpose-designed reduction gearboxes and

propellers, though transmission problems and structural failures proliferated

with small hulls that ‘worked’ in a seaway. Wood had the necessary resilience

and ease of repair where clad on timber or light alloy frames. All-aluminium alloy

hulls corroded disastrous salt-water conditions. As in the pre-transitional

navy, it was found that wooden hulls could not exceed a certain length and, for

instance in the British SGBs steel had to be used. A great British innovation

was to abandon traditional boat-building methods for mass production, using

prefabricated techniques. Once certain weaknesses had been rectified, this

system realized greater numbers of craft.

Hard-used fast coastal craft have a short operational life

and demand continual attention. Specialized depot ships, or tenders, enabled

squadrons to operate successfully ‘up-front’. The Americans particularly made

great use of them, offering off duty crews accommodation and facilities while

undertaking endless hull and machinery repairs, and servicing armament.

It had been assumed between the wars that coastal craft

would be needed in inshore ASW role, a belief that hung on until the British

SDBs of the 1950s. In the event, submarines generally operated further offshore

and those which were destroyed by small craft were despatched by torpedo while

navigating on the surface. Specialist AS boats were, therefore, rapidly

re-armed as gunboats, their depth charges removed. It remained the practice,

however, for many boats to retain a pair of charges for the deterrence of close

pursuit.

Small torpedoes of up to 457-mm (18-in) calibre proved to

have insufficient ship-stopping capacity, but the size and weight of two or

four 533-mm (21-in) weapons tended to dictate the parameters of the boats

themselves, to the extent that the Americans developed a special ‘short’

version. To save the weight of tubes, dropping gear was introduced, though this

left the torpedoes themselves vulnerable to damage. The Germans preferred to

retain their two enclosed tubes forward, with a reload for each stowed safely

behind a bulwark.

Close-in fighting was typically brief and bloody, involving

large volumes of volumes from light automatic weapons. Armour was gradually

introduced as a result the Germans going as far as an armoured wheelhouse.

Initially the British were at a disadvantage with only machine-guns to match

the German 20-mm cannon, whose explosive or incendiary shells were lethal to

wooden hulls loaded with petrol and ammunition.

As ever, armament developed to suit the need. American PT

boats, involved in the Far East against the eternal and apparently unstoppable

Japanese barge traffic, shed some or all of their torpedoes in favour of

weapons such as racked 127-mm (5-in) rockets and 81-mm (3.2-in) mortars.

British boats faced similar problems with the German MFPs, or ‘F’ lighters, in

such areas as the Aegean and Adriatic. Like the Japanese, these craft were of a

draught too shallow to be vulnerable torpedoes and could take aboard a variable

armament which often included much-respected 88–mm (3.46-mm) gun. British MGBs

responded appropriately, toting guns as large as the short-barrelled 114-mm

(4.5-in) gun.

Radar, available to small craft, was a boon in the vicious

nocturnal encounters where opponents could usually be seen only fleetingly and

for very short periods. Paradoxically, it was radar-controlled gunfire on the

part of larger ships that offset the torpedo boat’s advantages by effectively

outranging its main weapon.

Come the peace there was no sentiment, the boats being

deleted in hundreds destroyed by burning and many surviving a

swords-to-ploughshares transfiguration to become houseboats of surprising

durability.

Interest in small craft lapsed again on the part of the

larger navies until that day in 1967 when the Eilat became the first major SSM

casualty.