Warfare in Renaissance Italy

At the conclusion of the fifteenth century, Italy remained

divided. There were four kingdoms: Sardinia, Sicily, Corsica, and Naples; many

republics such as Venice, Genoa, Florence, Lucca, Siena, San Marino, Ragusa (in

Dalmatia); small principalities, Piombino, Monaco; and the duchies of Savoy,

Modena, Mantua, Milan, Ferrara, Massa, Carrara, and Urbino. Parts of Italy were

under foreign rule. The Habsburgs controlled the Trentino, Upper Adige,

Gorizia, and Trieste. Sardinia belonged to the kingdom of Aragon. Many Italian

states, however, held territories outside of the peninsula. The duke of Savoy

possessed the Italian region of Piedmont and the French-speaking Duchy of Savoy

along with the counties of Geneva and Nice. Venice owned Crete, Cyprus,

Dalmatia, and many Greek islands. The Banco di San Giorgio, the privately owned

bank of the republic of Genoa, possessed the kingdom of Corsica. Italian princes

also held titles and fiefdoms in neighboring states. Indeed, the duke of Savoy

could also claim that he was heir and a descendant of the crusader kings of

Cyprus and Jerusalem. All of this confusion often remained a source of

contention in Italian politics.

The Muslims became the greatest threat to security when the

Arabs occupied Sicily in the ninth century. Later Muslim attempts to conquer

central Italy failed as a result of papal resistance. Although the Norman

conquest of southern Italy and Sicily removed the immediate threat. Muslim

ships raided the Italian coast until the 1820s.

This conflict with Islam resulted in substantial Italian

participation in the Cru- sades. The Crusader military orders such as the

Templars and the Order of Saint John were populated by a great number of

Italian knights. Italian merchants, too, established their own warehouses and

agencies in the eastern Mediterranean and Black Sea. Thanks to the Crusades,

Venice and Genoa increased their influence as well. They expanded their

colonies, their revenues, and their importance to the Crusader kingdoms. Their

wealth exceeded that of many European kingdoms.

The fall of the Crusader kingdoms, the Turkish conquests,

and the fall of Constantinople by 1453 led to two significant consequences: the

increasing influence of Byzantine and Greek culture in Italian society, and the

growing Turkish threat to Italian territorial possessions in the Mediterranean.

The conflict between Italians and Muslims was complex. For centuries Italians and

Muslims were trading partners. So the wars between the Turks and Venetians

therefore consisted of a combination of bloody campaigns, privateering,

commerce, and maritime war lasting more than 350 years.

Despite a common enemy, common commercial and financial

interests, a common language, and a common culture, Italian politics remained

disparate and divisive. For much of the fifteenth century the states spent

their time fighting each other over disputed territorial rights. Although they

referred to themselves as Florentines, Lombards, Venetians, Genoese, or

Neapolitans, when relating themselves to outsiders, such as Muslims, French,

Germans, and other Europeans, they self- identified as “Italians.”

The Organization of Renaissance Armies

The lack of significant external threats led to the

reduction in size of Italian armies. The cost of maintaining standing armies or

employing their citizenry in permanent militias was too expensive and reduced

the productivity of the population. Italian city-states, duchies, and

principalities preferred to employ professional armies when needed, as they

were extremely costly to hire. Larger states, such as the Republic of Venice,

the Kingdom of Naples and the Papal States possessed a limited permanent force,

but the remainder of the Italian states had little more than city guards, or

small garrisons. Nevertheless, Italian Renaissance armies, when organized, were

divided into infantry and cavalry. Artillery was in its infancy and remained a

severely limited in application. Cavalry was composed of heavy or armored

cavalry, genti d’arme (men at arms), and light cavalry. Since the Middle Ages,

genti d’arme were divided into “lances” composed of a “lance chief”—or

corporal—a rider, and a boy. They were mounted on a warhorse, a charger, and a

jade respectively. The single knight with his squire was known as lancia

spezzata— literally “brokenspear,” or anspessade.

Infantry was divided into banners. Every banner was composed

of a captain, two corporals, two boys, ten crossbowmen, nine palvesai, soldiers

carrying the great medieval Italian shields called palvesi, and a servant for

the captain. Generally the ratio of cavalry to infantry was one to ten. There

was no organized artillery by the end of the fifteenth century, as it was relatively

new to European armies.

An Evolution in Military Affairs, or the So-Called

“Military Revolution”

Artillery was in its infancy during the fifteenth century,

but in the early days of the sixteenth century, a quick and impressive

development began. The Battle of Ravenna in 1512 marked the first decisive

employment of cannons as field artillery. Soon infantry and cavalry realized

the power of artillery and proceeded to alter their tactics to avoid or at

least to reduce the damage. Moreover, the increasing power of artillery

demonstrated the weakness of medieval castles and led to a trans- formation of

military architecture. The traditional castle wall was vertical and tall and

could be smashed by cannon-fired balls. In response, the new Italian-styled fortress

appeared. Its walls were lower and oblique instead of perpendicular to the

ground. The walls resisted cannonballs better, as their energy could also be

diverted by the obliquity of the wall itself. Then, the pentagonal design was

determined as best for a fortress, and each angle of the pentagon was

reinforced by another smaller pentagon, called a bastion. It appeared as the

main defensive work and was protected by many external defensive works,

intended to break and scatter the enemy’s attack. The fifteenth-century

Florentine walls in Volterra have many bastion elements, but the first

Italian-styled fortress was at Civitavecchia, the harbor for the papal fleet,

forty miles north of Rome. It was erected by Giuliano da Sangallo in 1519, but

recent studies suggest that Sangallo exploited an older draft by Michelangelo.

The classical scheme of the Italian-styled fortress often

referred to as the trace italienne was established in the second half of the

sixteenth century. Its elegant efficiency was recognized by all powers.

European sovereigns called upon Italian military architects to build these new

fortresses in their countries. Antwerp, Parma, Vienna, Györ, Karlovac,

Ersekujvar, Breda, Ostend, S’Hertogenbosch, Lyon, Char- leville, La Valletta,

and Amiens all exhibited the style and ability of Giuliano da Sangallo,

Francesco Paciotti, Pompeo Targone, Gerolamo Martini, and many other military

architects, who disseminated a style and a culture to the entire Continent. The

pentagonal style was further developed by Vauban and soon reached America, too,

where many fortresses and military buildings were built on a pentagonal scheme.

This evolution in military architecture—generally known as

“the Military Revolution”—meant order and uniformity. A revolution also

occurred in uniforms and weapons. Venetian infantrymen shipping on galleys for

the 1571 naval campaign were all dressed in the same way; and papal troops

shown in two 1583 frescoes are dressed in yellow and red, or in white and red,

depending on the company to which they belonged. Likewise, papal admiral

Marcantonio Colonna, in 1571, ordered his captains to provide all their

soldiers with “merion in the modern style, great velveted flasks for the

powder, as fine as possible, and all with well ammunitioned match arquebuses .

. . ” Of course, uniformity remained a dream, especially when compared with

eighteenth- or nineteenth-century styles, but it was a first step.

Although a revolution in artillery and fortifications

remained a significant aspect of the military revolution, captains faced the

problem of increasing firepower. The Swiss went to battle in squared

formations, but it proved to be unsatisfactory against artillery. Similarly,

portable weapons could not fire and be reloaded fast enough, and it soon became

apparent that armies needed a mixture of pike and firearms. The increasing

range and effectiveness of firearms made speed on the field more important. It

was clear that the more a captain could have a fast fire–armed maneuvering

mass, the better the result in battle. Machiavelli examined this issue; he was

as bad a military theorist as he was a formidable political theorist. He

suggested the use of two men on horseback: a rider and a scoppiettiere—a “hand-

gunner”—on the same horse. It was the first kind of mounted infantry in the

modern era. Giovanni de’Medici, the brave Florentine captain known as Giovanni

of the Black Band, adopted this system. Another contemporary Florentine

captain, Pietro Strozzi, who reduced the men on horseback to only one, developed

the same system. He fought against Florence and Spain, then he passed to the

French flag at the end of the Italian Wars. When in France, he organized a unit

based upon his previous experience. It was composed of firearmed riders,

considered mounted infantrymen, referred to as dragoons.

The Swiss

The Swiss (on the left) assault the Landsknecht

mercenaries in the French lines at the Battle of Marignano.

“As for trying to intimidate the enemy, blocks of

thousands of oncoming merciless Swiss, advancing swiftly accompanied by what a

contemporary called “the deep wails and moans of the Uri Bull and Unterwalden

Cow*” or landsknechts chanting “look out, here I come” in time with their drums

were posturing on a grand scale. Not to mention what 8 ranks of lowered

pike-heads looked like when viewed from the receiving end…”

The modern scholars Michael Mallett and Christine Shaw tell

us this about the Swiss mercenaries:

The French could boast the finest heavy cavalry in Europe

in the companies d’ordonnance, permanent units raised and paid for by the

Crown, in which the French competed to serve. For infantry, the French had come

to rely heavily on Swiss mercenaries. In the 1490s, the reputation of the Swiss

stood very high. They were a different kind of “national” army. A

well-established system of training, organized by the governments of the

cantons, resulted in a high proportion of able-bodied men having the strength

and ability to handle pikes, halberds and two-handed swords, and the discipline

to execute complex manoeuvres in formations of several thousand men.

Employers hired these men not only for their military skills

but also because entire contingents could be recruited simply by contacting the

Swiss cantons. Young men there were required to serve in the militia system,

were willing and well-prepared to do so, and welcomed the chance to serve

abroad. Alternatively, Swiss men could also hire themselves out individually or

in small groups. It is clear that the Swiss were hard fighters and hard-headed

businessmen as well. Their motto was: pas d’argent, pas de Swisse (no money, no

Swiss).

Swiss mercenaries were highly valued through late medieval

Europe because of the power of their determined mass attacks, in deep columns,

with pikes and halberds. They specialized in sending large columns of soldiers

into battle in “pike squares.” These were well-trained, well-disciplined bands

of men armed with long steel-tipped poles and were grouped into 100-man

formations that were 10 men wide and 10 men deep. On command, pike squares

could wheel and maneuver so quickly that it was nearly suicidal for horsemen or

infantrymen to attack them. As they came at their enemy with leveled pikes and

hoarse battle cries, they were almost invincible.

These Swiss soldiers were equally proficient in the use of

crossbows, early firearms, swords, and halberds. A These Swiss soldiers were

equally proficient in the use of crossbows, early firearms, swords, and halberds.

A halberd is an axe blade topped with a spike and mounted on a long shaft. If

the need arose, they could easily lay their pikes aside and take up other

weapons instead. They were so effective that between about 1450 and 1500 every

major leader in Europe either hired Swiss pikemen or hired fighters like the

German Landsknecht who copied Swiss tactics. The extensive and continuous

demand for these specialist Swiss and landsknecht pike companies may well have

given them the illusion of permanency. In any case, what it did show was that

medieval and Renaissance warfare was becoming better disciplined, more

organized, and more professional.

Swiss fighters were responding to several interrelated

factors: limited economic opportunities in their home mountains; pride in

themselves and their colleagues as world-class soldiers; and, last but not

least, by a love of adventure and combat. In fact, they were such good fighters

that the Swiss enjoyed a near-monopoly on pike-armed military service for many years.

One of their successes was the battle of Novara in northern Italy 1513 between

France and the Republic of Venice, on the one hand, and the Swiss Confederation

and the Duchy of Milan, on the other. The story runs as follows.

A French army, said by some sources to total 1,200

cavalrymen and about 20,000 Landsknechts, Gascons, and other troops, was camped

near and was besieging Novara. This city was being held by some of the Duke of

Milan’s Swiss mercenaries. A Swiss relief army of some 13,000 Swiss troops

unexpectedly fell upon the French camp. The pike-armed Landsknechts managed to

form up into their combat squares; the Landsknecht infantrymen took up their

proper positions; and the French were able to get some of their cannons into

action. The Swiss, however, surrounded the French camp, captured the cannons,

broke up the Landsknecht pike squares, and forced back the Landsknecht infantry

regiments.

The fight was very bloody: the Swiss executed hundreds of the

Landsknechts they had captured, and 700 men were killed in three minutes by

heavy artillery fire alone. To use a later English naval term from the days of

sail, the “butcher’s bill” (the list of those killed in action) was somewhere

between 5,000 and 10,000 men. Despite this Swiss success, however, the days of

their supremacy as the world’s best mercenaries were numbered. In about 1515,

the Swiss pledged themselves to neutrality, with the exception of Swiss

soldiers serving in the ranks of the royal French army. The Landsknechts, on

the other hand, would continue to serve any paymaster and would even fight each

other if need be. Moreover, since the rigid battle formations of the Swiss were

increasingly vulnerable to arquebus and artillery fire, employers were more

inclined to hire the Landsknechts instead.

In retrospect, it is clear that the successes of Swiss

soldiers in the 15th and early 16th centuries were due to three factors:

• Their courage was extraordinary. No Swiss force ever broke

in battle, surrendered, or ran away. In several instances, the Swiss literally

fought to the last man. When they were forced to retreat in the face of

overwhelming odds, they did so in good order while defending themselves against

attack.

• Their training was excellent. Swiss soldiers relied on a

simple system of tactics, practiced until it became second nature to every man.

They were held to the mark by a committee-leadership of experienced old

soldiers.

• They were ferocious and gave no quarter, not even for

ransom, and sometimes violated terms of surrender already given to garrisons

and pillaged towns that had capitulated. These qualities inspired fear in their

opponents.

Knights

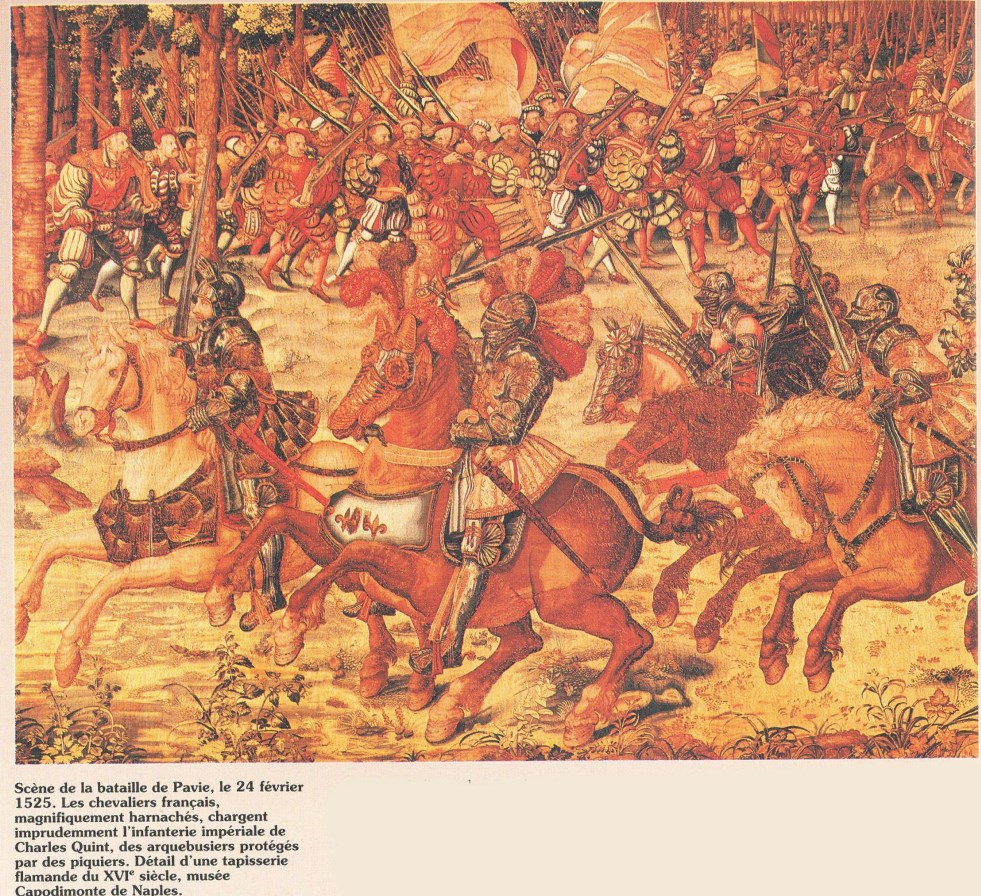

For all of their deficiencies, knights proved their mettle

against Byzantine and Muslim forces, and for nearly 250 years after the Battle

of Hastings (1066) they were all but invulnerable to the weapons used by

European infantrymen. At the Battles of Courtrai (1302) in the Franco-Dutch War

and the Morgarten (1315) in the First Austro-Swiss War, however, Flemish and

Swiss pikemen demonstrated that the proper choice of terrain allowed resolute

foot soldiers to defeat French and Austrian knights respectively. By then the

use of powerful crossbows and longbows also put knights at greater risk of

death on the battlefield at the hands of commoner bowmen. The combination of

archer and dismounted knight used by the English throughout the Hundred Years’

War (1337-1453) proved deadly effective against French knights. Men-at-arms

responded to their new vulnerability by using plate armor for themselves and

their horses, which were more likely than their riders to be killed in battle.

Plate armor presented several problems. It was too expensive for the less

wealthy nobles, so that the near equality in knightly equipment that had marked

the previous era disappeared. Its weight required larger and more costly

warhorses, which were slower and less maneuverable, allowing the men-at-arms to

do little more than a straight-ahead charge. Despite defeat by the Swiss

infantrymen in numerous battles throughout the fifteenth century, culminating

at Nancy (1477) in the death of Charles the Bold (1433-1477), the duke of

Normandy, armored horsemen remained a potent element, especially in the French

army.

A full suit of Italian plate armour circa 1450.

Renaissance armor was not just a means of protection,

but also a work of art. Some armor, like the suit shown here, had simple

borders cut into the metal. Other pieces displayed elaborate images of saints

or ancient heroes. The most expensive armor included designs in silver or gold.

Development of Armor.

Arms and armor changed significantly during the Renaissance,

with improvements in one of them often leading to modifications in the other.

New military tactics and techniques triggered some developments, while others

were based on fashion. Armor and weapons were not simply tools of war; they

also served important social and artistic functions.

The most popular form of armor during the Middle Ages was

mail—sheets of interlocking iron rings. Though flexible and strong, mail did

not protect as well as solid plates. In the 1200s armorers began making plate

armor out of materials such as leather and, eventually, steel. The earliest

plate armor protected the lower legs and knees, the areas that a foot soldier

could easily attack on a mounted knight. Over time, armor expanded to cover

more and more of the body.

By the early 1400s, knights were encased in complete suits

of overlapping steel plates. A full suit of armor might weigh as much as 60

pounds, but its weight was distributed over the entire body. A knight

accustomed to wearing armor could mount and dismount a horse fairly easily and

even lie down and rise again without difficulty. A foot soldier wore less armor

than a knight. He might have an open-faced helmet and a shirt of mail with

solid plates covering his back and chest.

Armor changed again as firearms became more common. Rigid

armor would crack when hit by a shot from a pistol or musket. Some armorers

responded by making their armor harder, while others produced plates that would

dent rather than breaking. However, the only really effective technique was to

thicken the armor, which made it too heavy to wear in battle. As armor became

less useful, soldiers tended to wear less of it. By 1650 most mounted fighters

wore only an open-faced helmet, a heavy breastplate, and a backplate. By 1700

armor had all but disappeared from the battlefield.

Tournaments called for special armor. Since participants did

not have to carry the armor’s weight as long as they would in battle, they wore

heavier armor that offered them greater protection. Each specific event in a

tournament required its own type of armor. Some contests involved battles

between mounted knights, while others featured hand-to-hand combat on foot.

Most armor, even that worn in battle, was decorated in some

way. The decoration ranged from etched borders around the edges of plates to

detailed images of saints or ancient heroes. Some very expensive armor was

inlaid with patterns in silver or gold. Highly decorated weapons and suits of

armor were status symbols, worn only at court or on special social occasions.

Development of Arms.

Renaissance weapons fell into three basic categories: edged

weapons, staff weapons, and projectile weapons. Edged weapons included swords

and daggers. Renaissance swords often had thin, stiff blades to pierce the gaps

between the plates in a suit of armor. The blades were usually straight and had

two sharpened edges, although some swords featured curved or single-edged

blades. Large swords swung with two hands were common among foot soldiers in

Germany and Switzerland.

A staff weapon, a pole with a steel head, was used to cut,

stab, or strike an opponent. Heavily armored mounted knights favored the lance,

a wooden shaft 10 to 12 feet long with a steel tip. Foot soldiers, especially

in Switzerland, often used the halberd, a 5- to 7-foot shaft with a head that

had both a cutting edge and a point for stabbing.

Projectile weapons were designed to hurl objects at great

speeds. The simplest of these, the sling, threw stones or lead pellets. Most

archers in the 1300s and 1400s used the longbow. Both it and the mechanical crossbow

could shoot arrows capable of penetrating plate armor at certain ranges. In the

1500s, firearms gradually took the place of bows.

The first pistols, called “hand cannons,” appeared in the

early 1300s. They were little more than a barrel with a handle, or stock. The

barrel had a chamber, or breech, that held shot and powder. The soldier loaded

powder into the open end of the barrel (the muzzle) and packed it tight with a

rod. The bullet went in after the powder. The gunner touched a lighted fuse to

a small hole in the barrel to ignite the powder and fire the shot.

Over the next few hundred years, various improvements made

firearms more reliable and easier to fire. The most important development was

the invention of firing mechanisms, known as locks, in the 1400s. The simplest

kind was the matchlock. It had an arm that held the lighted fuse. Pulling a

trigger turned the arm, touching the fuse to the powder. Even easier to use was

the wheel lock, which removed the need for a fuse. It ignited the powder by

striking a spark from a piece of iron pyrite when the trigger was pulled. A

variation of this, the flintlock, relied on flint to produce a spark.

Heavy cannons, or artillery, appeared about the same time as

firearms. Artillery pieces were loaded and fired in much the same way as

firearms, but they fired much larger stones and iron balls. The biggest

artillery pieces were used for castle sieges. The largest gun ever built could

hurl a 300-pound stone ball up to two miles. However, siege cannons weighed thousands

of pounds and could not be moved easily. By the late 1400s, field artillery had

been developed that could be mounted on wheels and transported. Cannons also

became common aboard ships. Like armor, many cannons were highly decorated with

designs or the owners’ coats of arms.