Piedmont proved to be an impenetrable barrier to every

advance from the French side of the Alps. The first attempt, by way of the

little-used Varaita valley, was checked by the entrenched position of the

Piedmontese near Casteldelfino in October 1743. In the following year the

French staff officer Pierre Bourcet (who was brought up in the Alps)

accomplished a clever concentration of 33,700 French and Spanish troops in the

Stura valley further to the south. This venture too came to an end in front of

a Piedmontese strongpoint, in this case the pentagonal fortress of Cuneo. The

place was held by 3,000 men under the command of a fine old Saxon soldier of

fortune, Major-General Leutrum, and few sieges have ever undergone such varied

and comprehensive misfortunes – disagreements in command, floods, and

guerrillas roving around on the lines of communication. The French and Spanish

raised the siege on the night of 21-22 October and marched back over the Alps,

having fired away 43,000 rounds of shot and bombs, and having lost 15,000 men

through enemy action, sickness and desertion.

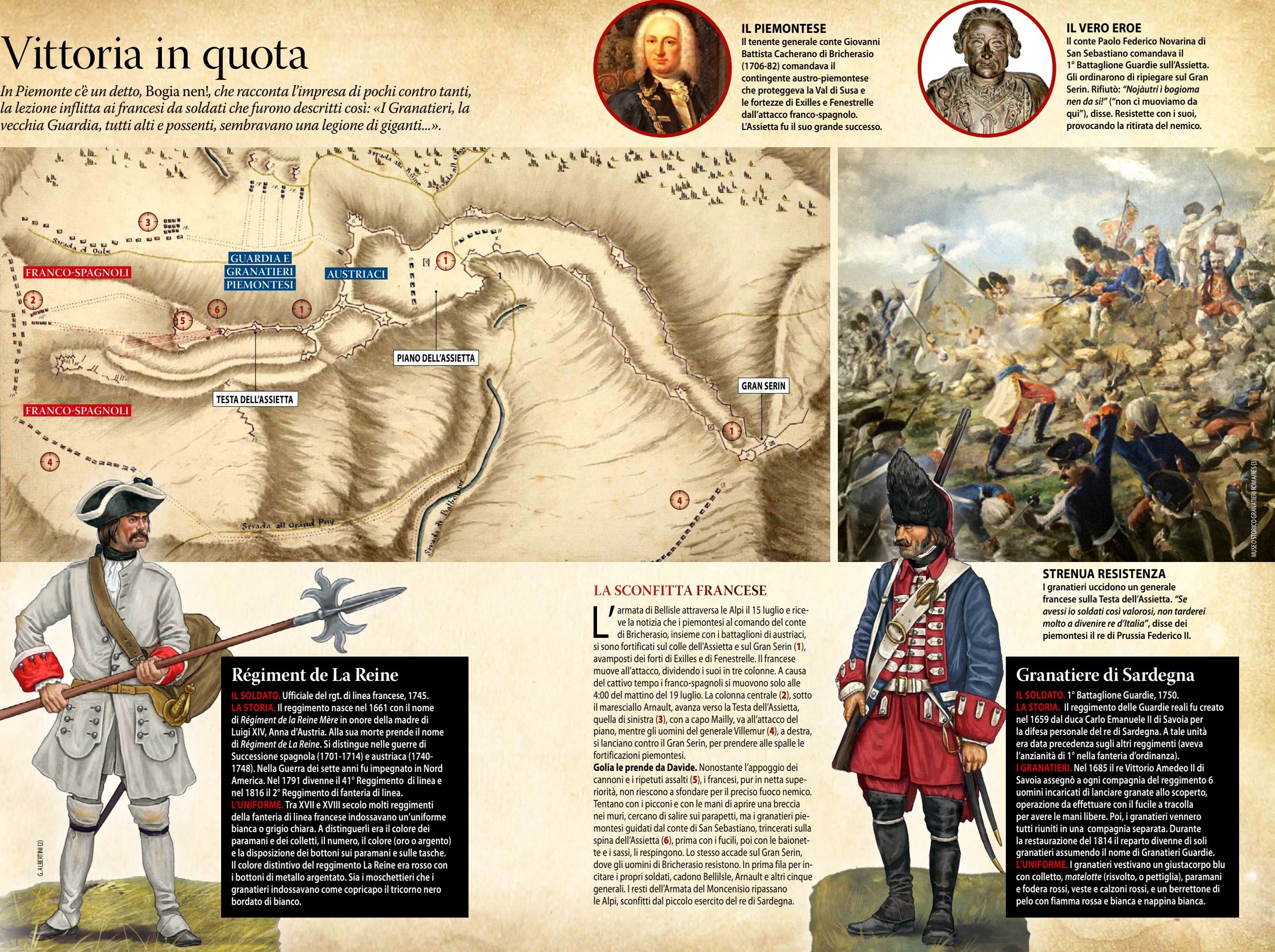

One final attempt to pierce the Alps, by way of the

Mont-Genevre route, was shattered on the ridge of the Colle dell’ Assietta on

19 July 1747.

#

In the spring of 1747, a new French army marched along the

Mediterranean coast. Charles Emmanuel ordered his troops to hold Nice, but soon

he knew that another French expeditionary force was approaching the Alps from

the west. If they crossed the Alps, they could effectively threaten Turin.

Charles Emmanuel had no troops to stem the invasion.

in June 1747 a French army under Marshal Belle-Isle advanced

along the Mediterranean coast, the siege of Genoa was lifted.

Now the French and Spanish decided on a concerted attack on

Savoy-Piedmont, hoping to knock it out of the war. While the Spanish were advancing north along

the Appeninnes, Marshal Belle-Isle attempted to advance through Stura

Pass. The marshal’s brother, the

Chevalier Belle-Isle would advance on Turin from further north. The French crossed Mont Genevre into Italy on

July 15th and 16th and were faced with two valleys, both heading toward their object

– Turin, the capital of Savoy. The

northern valley was protected by a fortress at Exilles. The southern valley was protected by the

Fenestrelle fortress. Between these two

valleys was the Colle della Assietta, a mountain with an elevation of around

8,000 feet. Seeing that the enemy could

pass along the ridge, and that a road over the ridge was the best connection

between the fortresses of Exilles and Fenestrelle, on June 29th the King of

Savoy had ordered that 3,000 workers start building a defensive line there. Numerous obstacles, redoubts and an 18 foot

high palisade, had been built on the slope.

To the south, the mountain descends 3,000 feet in around two

miles. To the north, it descends over

5,000 feet in around two miles to Exilles.

Terrain this difficult was greatly advantageous to the Allied

defenders. As an additional advantage,

they might descend from the mountain into the rear of an enemy army in the

valley. The French received bad

intelligence and believed that Colle della Assiatta was weakly defended.

The Sardinian had fortified the area with 13 infantry

battalions: 9 Sardinian, the remaining were Austrian and Swiss taken from the

troops that had unsuccessfully besieged Genoa.

After a delay of several days due to bad weather, the French

army advanced along the ridge on July 19, 1747 hoping to get behind the two

valley fortresses. If they could get

behind the Exilles fortress and capture it, the road to Turin would be

open. Instead they would meet the enemy

in difficult terrain and behind entrenchments.

That morning the Savoy army woke up early but found no enemy

to their front. Later in the day,

however, the French emerged. Rejecting

advice to delay an attack in order to prepare scaling ladders, Belle Isle

ordered an advance. Separating into

three columns, the French army of around 40,000 men moved on the enemy

position, since reinforced (including a few Austrian troops) to a total of

around 7,500 men in 13 battalions.

The French right column of 14 battalions under the command

of Marshal Villemur swung wide to the right and around much of the enemy

position to attack it on another section of the mountain. The effort failed.

The French left column of 9 battalions under General Mailly

was to move through a ravine and attack the enemy position.

The French center column of 8 battalions under Marshal

d’Arnaud was to attack the salient to their front. At 4:30, the French attacked.

The French attacks were a disaster. Belle-Isle was dead along with Marshal

D’Arnault and many other high ranking officers.

Montcalm, a colonel who would become famous in Canada during the next

war, was left wounded in a ditch overnight covered with bodies. After five hours of battle, the French

retreated.

What ensued in the late afternoon was celebrated as the most

one-sided slaughter of the war. Neither the flanking columns moved decisively

enough to influence events in. These, lashed by determined officers, the French

struggled up the slope, disassembling the various man-made impediments as they

proceeded, while withering musket fire from concealed and protected hideouts

exacted the heavy toll. Four times the French fell back before the onslaught;

each time they returned to the struggle. The living climbed over the piles of

dead as they tried to surmount the palisades. Defenders rained bullets and

rocks down on the relentless blood-drenched attackers. A retreat, more orderly

than the butchery, ensured.

The French lost around 5,000 men in all. Accounts give the losses of Savoy and its

allies at just 219. The Franco-Spanish

attempt to crush Savoy was a failure, and the war settled down in Italy after

the battle.

The beaten French troops returned to France. Frederick II of

Prussia, after hearing of news of the Sardinian defence at Assietta, declared

that, if he had had such valorous troops, he could easily become King of Italy.

The Peace of Aix-la-Chapelle, or Aachen, ended the war the

next year with Savoy gaining some territory.

The kingdom continued to survive and in the next century was prominent

in efforts to unify Italy: the King of

Savoy would become King of Italy.