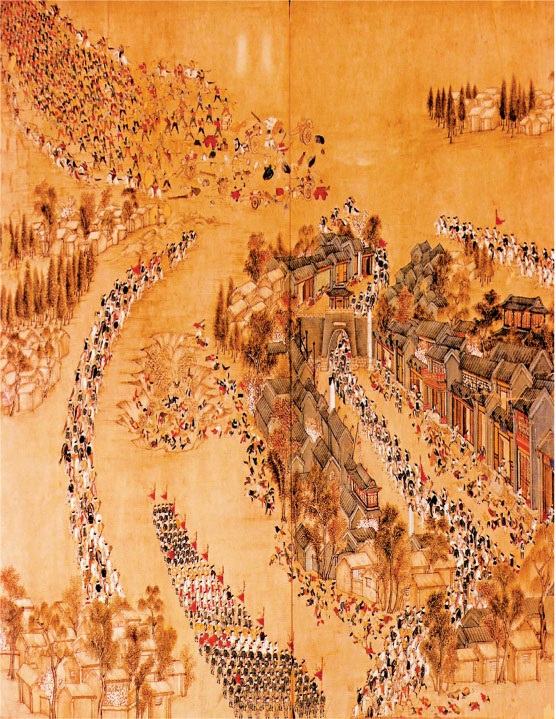

The Taiping forces’ victory over the Qing army in

capturing Nanjing is depicted here. The Taiping soldiers, were relentless in

training and became fierce fighters. Harvard Yenching Library.

The Qing army recaptured Nanjing in 1864.

After Issachar Roberts left him in the winter of 1862, Hong

Rengan had little contact with anyone else from the outside world. A stray

German missionary named Wilhelm Lobscheid finally came through Nanjing a year

and a half later, in the summer of 1863, while Gordon and the Anhui Army were

making inroads in Jiangsu province. He found the Shield King bitter and

defensive. “Have we ever broken faith with foreigners?” Hong Rengan asked him.

“Have we ever retaliated [against] the enmity of England and France?” If the

foreigners wanted to be the Taiping’s enemies, they had better beware, he said.

“We are fighting in our own country, and to rid ourselves of a foreign power, and

woe to the stranger who falls into our hands after the first shot has been

fired against Nanking.” Lobscheid was dismayed by the sting of betrayal he

heard in Hong Rengan’s voice and wished for a new beginning between the rebels

and the foreign powers. “Sir Frederick Bruce will one day be recalled to give

an account of the ruinous course of policy he has advised his Government to

adopt,” he wrote to a Hong Kong paper after his return from Nanjing, “and

foreign influence will at last prevail in the council of the rebels. But

whether that will be upon the ruins of the silk and tea plantations, or upon

the graveyards of thousands of British subjects, we shall soon have an

opportunity of witnessing.”

Though Hong Rengan no longer managed foreign affairs, he was

still the top-ranking official in the rebel court, and all of the capital’s

business still passed through his hands. For the most part, the other kings

still had to go through him to get access to his reclusive cousin the Heavenly

King. And once the anger about the doings of missionaries had faded, his cousin

gave him new responsibilities that in some ways were more personal, and

therefore more trusting, than the ones he had given him before. In 1863, he

asked Hong Rengan to take charge of his teenage son, the Young Monarch, and to

ensure his safety no matter what happened to Hong Xiuquan himself. As the

guardian of the heir apparent, Hong Rengan feared he might fall short “of the

great trust reposed in me,” and he was “filled with anxiety and gave way to tears.”

The immediate pressures of the war forced Hong Rengan to put

aside his plans for a new government and a new diplomacy for China. The

military campaigns and the supply lines simply had to come first, and as the

problems on those fronts intensified, the dawn of his imagined state receded

into the distance. His cherished reforms—the railroads, the law courts, the

trading entrepôts, the newspapers, mines, banks, and industries—would all have

to wait. It was all he could do to hold the leadership in the capital together.

Hong Xiuquan’s madness was growing as the military setbacks mounted, and

intimations of doom drove his visionary mind toward its longed-for apocalypse.

He refused to countenance a retreat, trusting only to the Heavenly Father, and

began granting rewards and honors to his followers with careless abandon,

creating so many new kings—more than a hundred of them—that his son the Young

Monarch couldn’t even keep all of their names straight. The bickering of the

officials in the capital was increasing and becoming more bitter, just at the

time when it shouldn’t.

#

Meanwhile, the famine in the countryside deepened. Despite

the relief stations Zeng Guofan had set up in southern Anhui, conditions in

that mountainous part of the province had deteriorated far beyond even the

horror that had existed when he first took control of Anqing. “Everywhere in

southern Anhui they are eating people,” he wrote in his diary on June 8, 1863,

a remark whose very banality signified the degree to which the unthinkable had

become commonplace. It was one of several notations on cannibalism in his

diary, though in this instance the concern that drove him to mention it wasn’t

so much that human meat was being consumed per se—for that was old news—but

that it was becoming so expensive: the price per ounce had risen fourfold since

the previous year, meaning that even this most dismal of sustenances was

becoming unaffordable. There was cannibalism in Jiangsu province as well, he

noted, east and south of Nanjing, though the price of human flesh there was

reported to be lower. Charles Gordon saw its gruesome footprint for himself

while on campaign, though he didn’t think his brethren back in Shanghai could

possibly understand the true horror of it. “[T]o read that there are human beings

eating human flesh,” he wrote to his mother, “produces less effect than if they

saw the corpses from which that flesh is cut.”

Northern Anhui was a wasteland. Bao Chao tried to scout out

a supply line through the province to support an army on the northern bank of

the Yangtze across from Nanjing, but he gave up hope. In normal times, the flat

midsection of Anhui was an unbroken plane of jade in the spring, with rice

shoots glowing in the open sun that dazzled in reflection off the threadlike

irrigation canals. But Bao Chao reported that in a journey of more than a

hundred miles through the region in the spring of 1863, he hadn’t seen so much

as a blade of grass. There was no wood to be burned for cooking fires. There

was nothing to support human life at all. Similar dark reports came from

Jiangsu, where the fighting had all but emptied the countryside for a hundred

miles around Shanghai. Wild pigs scavenged in abandoned villages, feeding on

the dried corpses of the dead. As governor-general, this was the region of Zeng

Guofan’s jurisdiction and lofty authority. “To hold such great responsibility

in such terrible times,” he brooded in his diary, “surely this is the most

accursed existence of all.”

Yet the desolation had its silver lining. Whether or not Zeng

Guofan actively supported a scorched-earth policy, he clearly saw in the

devastation of the landscape the same benefits for counterinsurgent warfare

that others, at other times in the world’s history, would find as well. In a

memorial to the throne on April 14, 1863, he described the ruin of southern

Anhui. “Everything is yellow straw and white bones,” he wrote. “You can travel

an entire day without meeting a single other person.” The most worrisome aspect

of this desolation, as he saw it, was that the rebels, denied any access to

food, might try to break out and head southwest into Jiangxi province.

At the same time, he explained, there was much to find

pleasing in the situation. The rebels depended on the support and acceptance of

the peasants among whom they lived, and the famine conditions would create

conflict. People would leave the regions surrounding the Taiping’s area of

control and “disappear like smoke,” leaving them without supporters. If the

farmers had no seeds, they would have to abandon their fields, leaving the

rebels with nothing to eat. “Campaigning in a region with no people, the rebels

will be like fish out of water,” he wrote. “In a countryside devoid of

cultivation, they will be like birds on a mountain with no trees.” The

devastation, he expected, would eventually reach the point where the rebels

could no longer survive.

#

Zeng Guoquan finally captured the stone fort on Yuhuatai on

June 13, 1863, in a sudden nighttime attack following months of quiet

preparation. He took the position with little loss of life, though Zeng Guofan

(who sought to gain as much credit for his brother as possible) reported to

Beijing that six thousand rebel defenders had been killed in the battle. With

control of the hill, Zeng Guoquan now effectively shut down the south gate.

From Zeng Guoquan’s new vantage point atop Yuhuatai, the rebel capital spread

out below like a giant Chinese chessboard. The game of encirclement was begun

for real now, and his elder brother, back in his chambers in Anqing, playing his

obsessive rounds of Go, laid his pieces carefully, plotting out the pattern of

moves that would surround the city, cut off all points of escape, and bring the

contest to its conclusion.

The western and northernmost gates of Nanjing opened onto

the Yangtze River, which ran past the city in a northeasterly direction. On the

bank of the river opposite the city lay gigantic Taiping forts that protected

the mile-wide Yangtze corridor as it skirted the capital. On June 30, the Hunan

river forces launched a furious attack on these forts. Taking advantage of a

strong crosswind, the Hunanese sent in wave after wave of sampans, which rode

in close-hauled on the downstream current, tacking sharply against the

headwind, then fired their guns and came about, sails spread wide, to run

before the wind that pulled them back upstream out of range in a grand whirl of

coordinated motion. The Taiping shore batteries blasted away at the circulating

sampans, wounding and killing more than two thousand Hunanese sailors, but in

the end the forts were taken and all of the defenders slaughtered. The Hunan

Army took full control of the Yangtze River where it met the northwest corner

of Nanjing, and the rebels could no longer make crossings to the north of the

city. The western gates of the city were now useless to them.

The last Taiping general to cross the river before the forts

were captured was Li Xiucheng, who returned on June 20 from an expedition to

the north. He had left Nanjing with an army in February 1863, three months after

he had failed to dislodge Zeng Guoquan from his camp at Yuhuatai, to try to

break through the Hunan Army forces in northern Anhui and open a new supply

line for the capital. His search through the wasteland of Anhui was as

fruitless as Bao Chao’s, and his troops were ravaged horribly by starvation in

the course of their journey. Reduced to eating grass, they still repeatedly

found the cities they attacked occupied by well-provisioned Hunan Army

garrisons that drove them off with heavy casualties. The news that Zeng Guoquan

had captured the fort on Yuhuatai in his absence was the final straw, and Li

Xiucheng returned straight to the capital when he heard. The army with which he

returned to Nanjing on June 20, crossing the river in stages ten days before

the forts on the north bank fell, was by his own estimate smaller by a hundred

thousand men than the one with which he had left in February. But no sooner did

he return to the side of his besieged sovereign than he had to leave again,

because his help was needed in Suzhou, which was threatened by Li Hongzhang,

and Hangzhou, under attack by Zuo Zongtang’s army. There were too many fronts,

too few commanders, too few resources.

Control of the river gave the Hunan forces dominance over

the western gates of the city, and with the southernmost gate shut down by his

brother’s position on Yuhuatai, Zeng Guofan turned his attention to the

northern and eastern faces of the city. Immediately after the river forts were

captured, he sent Bao Chao to cross over to the city and lay siege to the

Shence Gate, the primary inland gate on the city’s north side. In that alone he

was unsuccessful; disease broke out in Bao Chao’s camp, and a call for help

came from southern Anhui and Jiangxi, where the Hunan Army garrisons were contending

with the flight of Taiping armies headed westward from Zhejiang. So Zeng Guofan

had to remove Bao Chao from Nanjing and send him back to Anhui, leaving that

gate open.

Through the summer and autumn of 1863, Zeng Guoquan’s forces

continued to spread out, conquering a succession of ten heavily defended

bridges and mountain passes that gave them mastery of the roads southeast of

the city. In November, he sent a detachment northeast to the site of the Ming

imperial tombs in the hills just east of the city, where he had his men build a

three-mile wall linking to his southeastern positions, thereby blocking off the

eastern approach almost completely. On the eastern side of Nanjing, the only

gate that still remained open was the Taiping Gate, which opened outward a

couple of miles to the west of the Hunan Army’s blockade at the Ming tombs. Two

powerful rebel forts watched over it from the side of a precipitous mountain

that edged up against the city outside the wall at that point. The city-facing

slope of the mountain was known as the Dragon’s Shoulder, and the castle at its

top was the Fortress of Heaven, while the one at its bottom was the Fortress of

Earth. By December 1863, the Taiping Gate, with its two guardian fortresses,

along with the Shence Gate on the north side of the city that Bao Chao had

abandoned, were the only points of rebel control left on the city’s entire

twenty-three-mile circumference.

Quiet terror reigned inside Nanjing. With only the two gates

still open and therefore only two roads leading away from the city, food

supplies were limited and there was almost no traffic in or out. There were

about thirty thousand people inside the walls, a third of them soldiers. After

Suzhou fell to Li Hongzhang in December, Li Xiucheng returned again to Nanjing

and pleaded with the Heavenly King that they had to leave; they had to abandon

the capital and lead an exodus down into Jiangxi province. But the Heavenly

King refused, angrily accusing him of lacking faith. The sovereign’s

intransigence was maddening, but Li Xiucheng was unwilling to defy his orders

to stay put, so he began preparing the population inside for a prolonged siege.

There was one advantage, though, in there being so few people in such a vast

city. Under his direction they began opening up land in the northern part of

the city for cultivation. With hard work, they could grow enough food to

sustain themselves for a long time—perhaps even forever, if the walls held. But

the entrapped society was not at peace. Hong Xiuquan’s paranoia was mounting,

and even his cousin couldn’t temper the excesses of his mad cruelty. The people

lived in fear of his grotesque and capricious punishments. For the crime of

communicating with anyone outside the walls, people were now being pounded to

death between stones or flayed alive in public.

More might have fled the city and begged to be allowed to

shave their heads and return to the side of the dynasty, except that they knew

what had happened to the civilians in Anqing. By late December, they also knew

what had happened to the kings who had surrendered at Suzhou. Their judgment

was wise. Several groups of women were sent out from Nanjing over the following

months, and though they were not killed outright, in a fate more uncertain they

were “given” to the rural population as wives.18 But even that indulgence would

end. In the late spring of 1864, Zeng Guofan would advise his brother not to

let any more women or children escape the city. Forcing the rebels to support

the whole population inside, he explained, would accelerate their starvation.

And he didn’t want his brother to inadvertently let any of the rebels’ family

members survive.

With the Brave King dead and the Loyal King torn between

multiple fronts, Hong Rengan once again found himself thrust into military

command. As the exits from the city were cut off one by one, his cousin told

him to go out of the capital to rally troops from the nearby territories and

bring them back to relieve Nanjing. But even the military novice Hong Rengan

could sense that the tide had shifted. The death of the brilliant and

charismatic Brave King had left a vacuum in Anhui to the north and west of

Nanjing, and without him there it was now impossible to defend the capital from

northern approaches, impossible to reopen the river crossing and the northern

road through Pukou that had been their all-important outlet during the previous

siege of Nanjing. (Li Xiucheng’s attack on Hangzhou, which had broken that

earlier siege, had started on the very crossing they were now unable to control.)

There was no commander who could replace the Brave King, and despite the great

numbers of troops who had followed him gladly while he lived, now that he was

dead, his armies had dissolved, returning to their homes, heading north to join

the Nian, or surrendering to the imperial side. “With the fall of the Brave

King, the prestige of the troops was gone,” wrote Hong Rengan in reflection,

“and as a matter of course they dispersed.” To make matters worse, the news

came that even Shi Dakai the Wing King had surrendered with his renegade army

in Sichuan during the summer, and there was no longer any hope of his coming to

the aid of Nanjing either.

Hong Rengan set out from the capital on the day after

Christmas 1863, leaving his brother and his wives and children behind in

Nanjing. He journeyed first to Danyang, fifty miles to the east, where the

Green Standard generals had met their end in 1860. The uncle of the Brave King

commanded the garrison there, but he said there were no soldiers to spare for

Hong Rengan to take back to Nanjing. So he prepared to continue onward, toward

Changzhou, thirty miles farther east along the Grand Canal. But then the news

came that Changzhou had fallen to Li Hongzhang’s army, and he had to stay in

Danyang through the winter. When spring broke, he traveled south into Zhejiang

province, where the city of Huzhou, fifty miles north of the capital, Hangzhou,

was still holding out.

When Hong Rengan had gone out to raise an army back in 1861,

the process of recruitment had been almost effortless—simply a matter of

planting his standard, writing his poems, and then waiting as the multitudes

came to him to lead them into battle. But not anymore. In both Danyang and

Huzhou he found only vulnerability, not strength. The commanders were worried

about attacks from the imperial forces who had just conquered Suzhou and

Changzhou. The soldiers were afraid of food shortages and refused to leave the

relative safety of their garrisons to follow him back to the capital. In

compromise, he made a home for the summer in Huzhou, promising the commanders

that he would wait there with them until September, when the new harvest of

grain in Nanjing would be ready to feed them all and they could march together

back to the capital.

Meanwhile, new recruitment was swelling the Hunan Army to an

unprecedented size. By January 1864, there were 50,000 Hunan soldiers at

Nanjing. In total, Zeng Guofan commanded some 120,000 troops, about 100,000 of

them on land and the rest in the river navy. Along with the 50,000 under his

brother at Nanjing, there were 20,000 garrisoned in southern Anhui, 10,000 in

northern Anhui, 13,000 roving with Bao Chao, and 10,000 stationed between Anhui

and Suzhou. And that wasn’t even counting Li Hongzhang’s Anhui Army, which

followed up its conquest of Suzhou with a march toward Nanjing from the east,

smashing through the walled cities of Wuxi and Changzhou in rapid succession.

Nor did it count the army under Zuo Zongtang in Zhejiang province, fighting its

way toward Hangzhou in preparation to come at Nanjing from the south. All of

the forces were converging.

As the armies expanded, the battles continued to go their

way. In February 1864, Zeng Guoquan’s forces managed to capture the castle at

the peak of the Dragon’s Shoulder, the Fortress of Heaven. The rebels still

held the Fortress of Earth at its base, which guarded the point where the

mountain ridge met the city wall. But with the control of the upper fort, the

imperials dominated the field, and they were able to set up stockade camps at the

Shence Gate and the Taiping Gate against little resistance. Once those final

two gates were invested, the city was closed off completely. Soon afterward, on

March 31, the Zhejiang capital, Hangzhou, fell to Zuo Zongtang with support

from the French-Chinese force out of Ningbo. The defenders who escaped the

fallen city fled to Huzhou, fifty miles to the north, where they found refuge

with Hong Rengan through the summer. The other rebel armies that were scattered

throughout Zhejiang began abandoning the province, moving in a disorganized

retreat westward into Jiangxi. With the loss of both Hangzhou and Suzhou, the

Taiping no longer held any of the major eastern cities. There were no more

avenues of rescue for the capital. All there was left was the siege.