The agreeable monotony of Roosevelt’s schedule for late June

1907 was interrupted on the twenty-seventh by a captain from the General Board

of the Navy and a colonel from the Army War College. They accompanied Victor H.

Metcalf, the Secretary of the Navy, and Postmaster General George von L. Meyer,

who had definitely not come to discuss rural free delivery. Meyer’s presence,

indeed, helped explain his real role in the Cabinet, which was to advise the

President on questions of extreme diplomatic delicacy.

Five weeks before, after returning to Washington from Pine

Knot, Roosevelt had been exasperated to hear that anti-immigrant riots had

broken out in San Francisco. “Nothing during my Presidency has given me more

concern than these troubles,” he wrote Kentaro Kaneko. He argued that what was

happening in California was nothing new. Nor was it essentially racial: it had

plenty of precedents in European history over the last three centuries.

France’s Huguenots, for example, had been as white as their coreligionists in

Great Britain, but when they immigrated there, they had excited “the most

violent hostility,” indistinguishable from what had happened at the Golden

Gate. Then as now, mobs of workmen caused most of the trouble, expressing

labor’s chronic fear of being devalued by competition. Now as not then, hope

lay in the increased ability of “gentlemen, all educated people, members of the

professions, and the like” to visit one another’s countries and “associate on

the most intimate terms.” This was the particular responsibility of elected

representatives. “My dear Baron, the business of statesmen is to try constantly

to keep international relations better, to do away with the causes of friction,

and to secure as nearly ideal justice as actual conditions will permit.”

Meyer himself could not have put the case with more finesse.

But the fact remained that coolies were still coming, and having their faces beaten

in. The Immigration Act was still not working as it should, the San Francisco

Police Board had taken up where the school board had left off, reactionary

newspapers were screaming, and Japanese opposition leaders were calling for

war.

Elihu Root did not take the last threat seriously. He wrote

Roosevelt to say that alarmists had their own agenda, but “this San Francisco

affair is getting on all right as an ordinary diplomatic affair.… There is no

occasion to get excited.”

Roosevelt was not so sure. Japan had behaved with

commendable restraint during the early months of the crisis. Recently, however,

he had begun to detect “a very, very slight undertone of veiled truculence” in

her communications concerning the Pacific coast. He heard from members of his secret

du roi that the Japanese war party really did think the United States was

beatable. The Office of Naval Intelligence reported evidence of Japanese war

preparations, including purchase orders for nearly eighty thousand tons’ worth

of armored vessels from Europe, and a twenty-one-thousand-ton dreadnought from

Britain. (So much for any chance of a disarmament agreement at the Second Hague

Peace Conference, now in session.)

His responsibility as Commander-in-Chief was to look to the

nation’s defenses. Hence the arrival at Sagamore Hill of two top military

strategists. He had asked them to bring him contingency plans, “in case of

trouble arising between the United States and Japan.”

Colonel W. W. Wotherspoon and Captain Richard Wainwright

proved to be little more than messengers, delivering a somewhat obvious finding

by the Joint Board of the Army and Navy. The board stated that because Japan’s

battleships were all in the Pacific, and those of the United States in the

Atlantic, the latter power should “take a defensive attitude” in any

confrontation, until its heavy armor could be brought around Cape Horn.

Roosevelt said, for the record, that he did not believe

there was any real chance of a war with Japan. Then he approved the only

controversial aspect of the Joint Board’s report: a recommendation by Admiral

Dewey that “the battle fleet should be assembled and despatched for the Orient

as soon as practicable.”

The idea was not new. For at least two years, the Navy had

considered transferring the fleet from one ocean to the other as a tactical

exercise, but had never managed to decide the extent of the move, or the

logistics of support. Fuel supplies were a particular problem, and the West

Coast of the United States was short on bases. Dewey calculated that it would

take at least ninety days to mount an emergency battle presence in the Pacific.

“Japan could, in the meantime, capture the Philippines, Honolulu, and be master

of the sea.”

Roosevelt considered the options, and his own as President

and Commander-in-Chief. He had just seventeen months left in office, and wanted

to make a grand gesture of will, something that would loom as large

historically in his second term as the Panama Canal coup had in his first. What

could be grander, more inspirational to the Navy, and to all Americans, than

sending sixteen great white ships halfway around the world—maybe even farther?

And what better time than now, when positive news was in such short supply?

Wall Street’s stock slide in March had caused many brokerage houses to fail and

bank reserves to drop. Foreign markets had also begun a steady decline, with

stocks plummeting in Alexandria and Tokyo, Frenchmen hoarding more gold than

usual, and even the Bank of England low on cash. Jacob Schiff had said that

“uncertainty” lay at the bottom of all distrust. All the more reason, then, to

make one highly visible arm of the United States government look quite certain

of itself, as it moved from sea to shining sea.

The massive deployment appealed to Roosevelt as diplomacy,

as preventive strategy, as technical training, and as a sheer pageant of power.

There was also the enormity of the challenge. He had private information that

neither British nor German naval authorities believed he could do it. Well, he

would prove them wrong. “Time to have a show down in the matter.”

He issued a series of orders to Secretary Metcalf. The Subic

Bay coal stockpile in the Philippines must be enlarged at once. Defense guns

must be moved there from Cavite. Four armored cruisers of the Asiatic Fleet were

to be brought back to patrol the West Coast. And finally—Roosevelt’s operative

order, climaxing ninety minutes of talk—the Atlantic fleet would set sail from

Hampton Roads, Virginia, in October, destination San Francisco.

When someone asked how many battleships would make the trip,

Roosevelt said that depended on how many there were in service at the time. If

fourteen, he would send fourteen; if sixteen, then sixteen. He wanted them “all

to go.”

Metcalf was authorized to announce the dispatch of the “Great

White Fleet”—as it soon became known—appropriately on the Fourth of July. But

the news was too big to hold, in view of the tense state of American-Japanese

relations. By the time the Secretary issued his statement, Ambassador Aoki had

already moved defensively to say that Japan did not regard Roosevelt’s gesture

as “an unfriendly act.”

His Excellency thus avoided sounding overjoyed at the

prospect of an enormous alteration in the balance of naval power in the

Pacific. And Roosevelt, by intimating that San Francisco would be the fleet’s

farthest port of call, encouraged Californian alarmists to think it was being

dispatched for their protection. They would have been less comforted if they

had known that he was privately talking to Henry Cabot Lodge about sending it

on “a practice cruise around the world.”

#

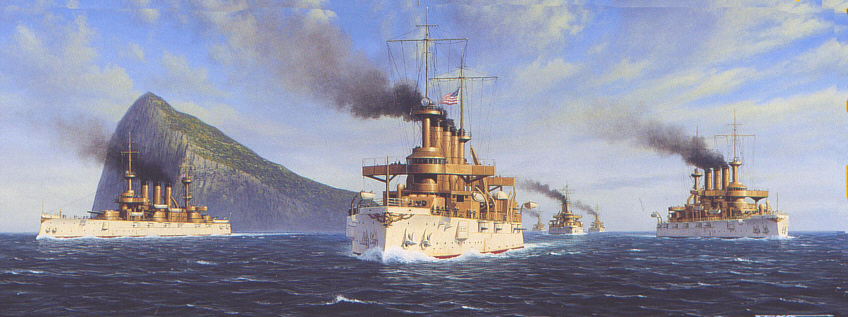

Monday, 16 December, broke sunny, sharp, and clear over the

James River estuary after a weekend of heavy rain. All sixteen ships of the

battle fleet lay waiting for him, blindingly white in the eight o’clock light,

as the Mayflower creamed into the Roads and proceeded past each gold-curlicued

bow. The air drummed with 336 cannon blasts, not quite dividing into

twenty-one-gun strophes.

“By George!” Roosevelt exulted to Secretary Metcalf. “Did

you ever see such a fleet and such a day?”

When the presidential yacht came to anchor, gigs and barges

brought aboard “Fighting Bob” Evans—a surprisingly small, fierce-faced man,

limping with rheumatism—four rear admirals, and sixteen commanding officers.

Roosevelt made no speech after shaking all their hands, only drawing Evans

aside for a few minutes and muttering to him with earnest, snapping teeth.

Bystanders watched the admiral’s cocked hat bobbing like a gull as Roosevelt

bit off sentence after sentence. What scraps of dialogue floated on the breeze

were mostly banal: “I tell you, our enlisted men … perfectly

bully … best of luck, old fellow.”

Less audibly, the President was giving Evans secret orders

to stay in the Pacific for several months, then proceed home via the Indian

Ocean and Suez Canal. Cameras clicked as the two men bade each other farewell.

The commanders returned to their ships, and, as the Mayflower got under way for

Cape Henry, one by one the battleships weighed anchor and hauled around in

stately pursuit. They overtook Roosevelt at the mouth of Chesapeake Bay and

ground past him in a perfectly spaced, three-mile-long column. He watched with

intent seriousness, periodically doffing his top hat, until the Kentucky, the

last unit of the Fourth Division, moved by in a vast white wall, all its

sailors saluting.

#

On 7 February, the Great White Fleet, dispatched toward

unknown possibilities by an allegedly deranged (William James preferred the

term dynamogenic) Commander-in-Chief, entered the Strait of Magellan. Since

leaving Hampton Roads, it had become a diplomatic phenomenon, attracting

worldwide press attention and spreading as much goodwill as foam along the

Brazilian and Argentine coastlines. Even Punta Arenas, Chile, a windswept

wood-and-iron outpost near the extreme tip of the continent, welcomed Admiral

Evans and his sailors with elaborate hospitality and specially hiked prices.

For twenty-two hours, the Chilean destroyer Chacabuco led

Evans’s flagship Connecticut through the misty Strait—a surreal Doppelgänger of

the waterway being carved across Panama—while fifteen other coal-heavy ships

wallowed behind at four-hundred-yard intervals. No more than three men-of-war

had ever performed this maneuver in convoy, and the going was hazardous even

for single units. But the fleet steamed steadily through. It veered off course

only once, when a sudden turbulence proclaimed the conflicting levels of two

oceans. By the time the last vessel emerged into open sea, the first was

already steaming toward Valparaiso, and the Pacific theater had received its

largest-ever infusion of battleships.

Roosevelt had still not announced his intention to send the

fleet around the world—its official destination remained San Francisco. But

Japan was aware that another war scare in the United States could quickly alter

the fleet’s course; Admiral Dewey’s “ninety-day lag” no longer applied. This

knowledge, combined with mounting diplomatic pressure from Elihu Root, now

forced the conclusion of the “Gentlemen’s Agreement,” on which Tokyo had been

politely stalling for nearly a year.

Throughout 1907, the influx of Japanese coolies into the

United States had continued to pour unabated, making a mockery of the new

immigration law. Root had tired of pointing out that the flow had to be restricted

at its source, as per Tokyo’s verbal promise. Instead, he had taken advantage

of the publicity attending the dispatch of the Great White Fleet to warn

Ambassador Aoki that unless there was “a very speedy change in the course of

immigration,” the Sixtieth Congress was certain to pass an exclusion act,

greatly to the detriment of Japanese-American relations.

By 29 February, as the fleet headed north from Callao, Peru,

the Gentlemen’s Agreement was finally implemented. Coolies were no longer

permitted to immigrate to Hawaii, passport restrictions were tightened, and

illegal agencies were being prosecuted by Japanese authorities. And at last,

the monthly “Yellow Peril” index compiled by the State Department began to

decline.

Roosevelt celebrated by confirming that the Great White

Fleet, now en route to the Golden Gate, would proceed around the world after a

couple of months’ rest and refitting. Its itinerary would include Hawaii, New

Zealand, Australia, the Philippines, Japan (about two weeks before the

presidential election), China, Ceylon, the Suez Canal, Egypt, the

Mediterranean, and Gibraltar. Its due date for return to Hampton Roads was 22

February 1909, ten days before he was to leave the White House.

#

Pulverizing as the President’s Special Message had been to

the boomlet for Governor Hughes, and however revealing of Roosevelt’s own

changing ideology, it merely increased the opposition of congressional

conservatives against him. Joseph Cannon in the House and Nelson Aldrich in the

Senate vied with each other to deny him the reforms he had begged with such

eloquence. However, a small band of progressive Republicans and a larger one of

moderate Democrats (who had applauded repeatedly during the reading of the

Message) helped him win at least three new laws: a re-enacted Federal

Employers’ Liability Act, the Workman’s Compensation Act for federal employees,

and the Child Labor Act for the District of Columbia.

He also won, on 10 March, a nonlegislative victory with

fruits that tasted distinctly sour. The Senate Committee on Military Affairs

concluded its thirteen-month investigation of the Brownsville affair and found,

by nine votes to four, that Roosevelt had justifiably dismissed without honor

the soldiers of the Twenty-fifth Infantry. Three thousand pages of testimony,

and the congruent opinions of virtually all Army authorities from the

Commander-in-Chief on down, were enough to convince five Democrats and four

Republicans that the men were guilty. The dissenting members were all

Republican, but they were themselves divided, in a way that paradoxically

compromised the majority vote. Two found the testimony to be contradictory and

untrustworthy, reflecting irreconcilable antipathies between soldiers and

townspeople. Senators Foraker and Morgan G. Bulkeley insisted that “the weight

of the testimony” showed the soldiers to be innocent.

So did the weight of the only hard evidence in the case:

thirty-three spent Army-issue cartridges found at the scene of the crime.

Ballistics experts had testified that, while the shells had definitely been

fired by Springfield rifles belonging to the Twenty-fifth, the actual firing

had occurred during target practice at Fort Niobrara in Nebraska, long before

the battalion was ordered to Texas. The mystery of the translocation of the

shells to Brownsville was simply explained. Army budget officers frowned on

waste of rechargeable ordnance, so 1,500 shells had been recovered from the

range, sent south, and stored in an open box on the porch of a barracks hut at

Fort Brown, available for any soldier—or passing civilian—to help himself.

Such technical information, however, could not explain away

the “wooden, stolid look” that Inspector General Garlington had seen on the

faces he interviewed. It was a look so evocative of Negro complicity that the

War Department had briskly dispensed with the formality of allowing every

soldier his day in court.

Roosevelt’s other major legislative request, unsatisfied

through the first weeks of spring, was for four new battleships. The House

followed the recommendation of its Committee on Naval Affairs and appropriated

funds for only two. Unappeased by an extra appropriation to build a naval base

at Pearl Harbor, Roosevelt put his hopes in the Senate. Debate there began on

24 April, none too favorably. Senators seemed more inclined to question the

legality of his battle-fleet cruise order than to double the battleship quota

of the House bill. But they also had to take into account his still phenomenal

popularity, and the hold the Great White Fleet had taken of the public

imagination. Three days later, Roosevelt won a modified victory: two

battleships plus a guarantee that two more would be funded before he left

office.

Sounding rather like a small boy, he claimed not to have

expected four all at once, but had asked for them only because he wanted to be

sure of getting two.

During the reign of King Kalākaua the United States was

granted exclusive rights to enter Pearl Harbor and to establish “a coaling

and repair station.”

Although this treaty continued in force until August 1898,

the U.S. did not fortify Pearl Harbor as a naval base. As it had for 60 years,

the shallow entrance constituted a formidable barrier against the use of the

deep protected waters of the inner harbor.

The United States and the Hawaiian Kingdom signed the

Reciprocity Treaty of 1875 as supplemented by Convention on December 6, 1884,

the Reciprocity Treaty was made by James Carter and ratified it in 1887. On

January 20, 1887, the United States Senate allowed the Navy to exclusive right

to maintain a coaling and repair station at Pearl Harbor. (The US took

possession on November 9 that year). The Spanish–American War of 1898 and the

desire for the United States to have a permanent presence in the Pacific both

contributed to the decision.

Following the overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom, the United

States Navy established a base on the island in 1899.