The Sinai t 1400 hours on 6 October 1973 the Arabs launched

a surprise two-front assault on the Israelis under the codename of Operation

Badr. Egyptian and Syrian armour swept all before them and the state of Israel

teetered on the very brink of collapse. It was Yom Kippur, the Jewish fast day,

when Israel was least prepared for war. The Israeli Defence Forces (IDF),

suffering staggering losses, struggled desperately to stem the tide, and then a

miracle happened – the Arab Biltzkrieg was killed in its tracks.

The Egyptians had around 1,650 T-54/55 tanks plus about 100

of the more modern T- 62s; the Syrians had about 1,100 T54/55s and an unknown

number of T-62s; between them they also had about 300 Second World War-vintage

T-34s. As the battle progressed Iraq committed up to 250 T-54/55s and Jordan

fielded about 100 Centurions. During the fighting the Soviet Union shipped in

another 1,200 tanks to Egypt and Syria as battlefield replacements.

Following the 1967 Six Day War Israel had been left in

control of the Egyptian Sinai desert, the Palestinian Gaza Strip, the Syrian

Golan Heights and the Jordanian West Bank and East Jerusalem. The upshot was

that for the first time Israel had some good natural defensive barriers to

protect its borders. Six years later Egypt and Syria and their neighbours were

determined to recapture this lost territory. By 1973 the Arab armies were armed

to the teeth thanks to the Soviet Union, which had equipped them with T-54/62

tanks, MiG fighter jets, missiles and artillery. Holding the Egyptian,

Jordanian and Syrian frontiers was the `Zahal’, or IDF, consisting of just

75,000 regulars and reservists.

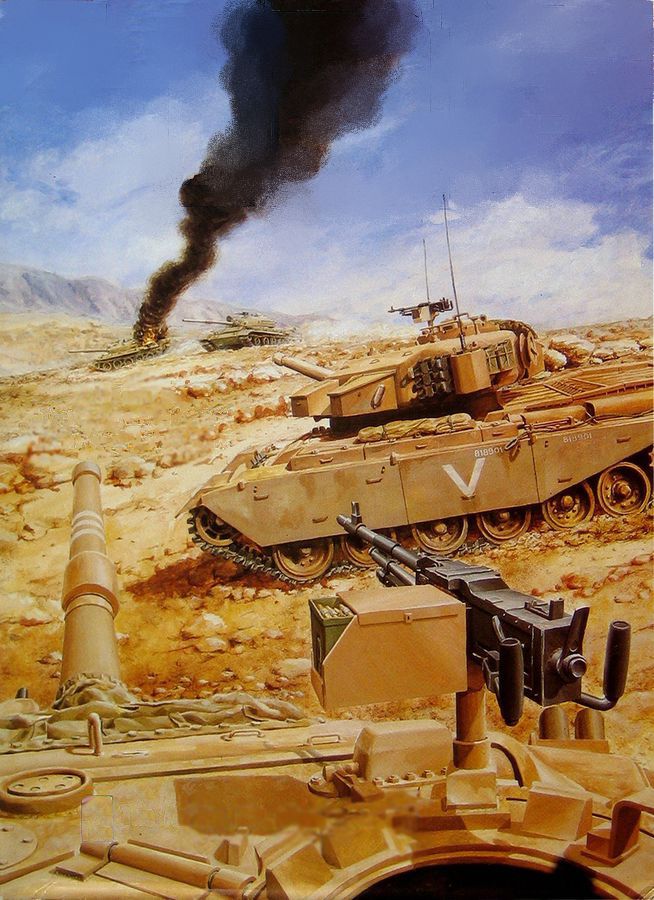

The Israeli triumph during the Six Day War and the key role

played by their armoured corps ensured its central role in post-war planning.

After 1967 Israel upgraded its M48s to produce the Magach 3 and 5, followed by

the M60 upgrade known as the Magach 6 and 7. Another M60 upgrade in the 1990s

produced the Sabra. The Israelis captured several hundred repairable T-54s and

T-55s and these were modified and reissued for Israeli use as the Ti-67 or

Tiran. Similarly, captured T-62s were reissued as the T-62I.

The French-supplied AMX-13 proved to be wholly inadequate

when they came up against the Egyptian T-54s and were relegated to a reconnaissance

role. Likewise the Israeli M3 half-tracks, which had been in service since

1948, were now too vulnerable and were replaced by the American M113 tracked

armoured personnel carrier – which the Israelis call the Zelda.

Israel’s 252nd Armoured Division, with around 280 tanks in

three brigades, was deployed along the Suez Canal supported by three reserve

armoured divisions. Across the canal, massing for the attack were ten Egyptian

divisions supported by 1,600 tanks, all organised into two armies. The key

Egyptian armoured formations were the 4th and 21st armoured divisions and the

3rd, 6th and 23rd mechanised divisions. They were supported by various foreign

allied contingents, which included Algerian and Libyan armoured brigades.

General Gonen was in charge of Israel’s Southern Command,

which included the 143rd, 162nd, and 252nd armoured divisions – in all, these

mustered some nine armoured brigades. Once the Syrian front had been stabilised

these forces were later reinforced by elements of the 146th and 440th composite

divisions.

The Egyptian offensive was to take them over the canal

between Kantara and Ismailia and to the south of Great Bitter and Little Bitter

lakes in the Suez City area. These two separate crossings, by the Egyptian 2nd

and 3rd armies respectively, divided by the two lakes immediately betrayed a

fatal flaw that the Israelis would later capitalise on.

The armoured forces supporting the Egyptian 2nd Army

comprised the 21st Armoured (with two tank brigades and one mechanised brigade)

and the 23rd Mechanised (two mechanised brigades and one tank brigade)

divisions. The armoured spearhead of the 3rd Army was the 4th Armoured and 6th

Mechanised divisions, while the Egyptian GHQ had the 3rd Mechanised Division

plus an independent tank brigade held in reserve.

The Egyptian assault opened with 2,000 guns firing a deluge

of 100,500 shells at the Israeli defences known as the Bar-Lev Line. Then 150

MiG fighters attacked Israel’s air bases, command posts and communications

centres. When the Israeli Air Force tried to intervene it was met by a barrage

of Soviet-supplied surface-to-air missiles (SAMs). The Israeli Air Force lost a

huge number of planes, though only fifteen were actually downed in air-to-air

combat.

During the early 1970s the Egyptians and Syrians, with

Soviet assistance, constructed SAM networks even more formidable than those

used by North Vietnam. The Arabs also deployed the SA-6 for the first time and

it was this that posed the greatest threat to the Israeli Air Force. Being fully

mobile, with unknown target-acquisition radar frequencies, the Israelis were

reduced to the expedient of dropping Second World War-style `chaff’ to blind

it. Crucially the Israelis greatly benefited from America’s experiences in the

Vietnam War. The SA-2 and SA-3, also used by the Egyptians, were relatively

immobile and most of their codes had been broken. Nor did the SA-6 threat last

long either.

The Egyptians’ phased attack was designed first to cross the

canal, neutralise the Israeli defences on the eastern bank, establish

divisional bridgeheads to meet the inevitable Israeli counter-attacks and then

link up the bridgeheads. Using high-pressure hosepipes the Egyptians breached

the Israeli sand berm protecting the eastern bank and threw a series of pontoon

bridges over the Suez Canal. Getting across the canal was a considerable feat

and there were three reasons why it was achieved: firstly, choosing Yom Kippur

(the Day of Atonement) which was one of the holiest days for the Jews;

secondly, meticulous planning; and thirdly, the Egyptians had a much more

sophisticated air defence system than in 1967, which for a while at least kept

the Israeli Air Force at bay.

The crossing of the Suez Canal was the first time that the

Soviets got to operationally test their PMP Floating Bridge, which had been

developed to tackle Europe’s wide rivers. This consisted of box-shaped pontoons

carried on tracked vehicles – hydraulic arms deployed the first pontoon, a

vehicle would then drive onto the pontoon and deliver a second section and so

on. The PMP was able to lay the pontoons at a rate of about fifteen feet a

minute, so the Egyptian engineers were able to get over the canal in just under

half an hour. Using old-style Second World War pontoon bridging would have

taken the Egyptians at least two hours. The net result was that Egypt’s tanks

were soon rumbling over the canal at a faster rate than anticipated by Israeli

intelligence. Within ten hours the Egyptians successfully deployed 500 tanks

and their protective air defence system on the eastern bank. This was to be the

high point of Egyptian military achievements.

The Egyptian 2nd and 3rd armies successfully swarmed across

and fought off twenty-three desperate Israeli counter-attacks over the next two

days. During Operation Badr the Egyptians got about 1,000 tanks over the Suez

Canal; they left 330 tanks as an operational reserve behind on the west bank,

while there was also a strategic reserve of another 250 tanks – though 120 of

the latter were from the Presidential Guard and would only be released in the

direst of emergencies.

The Egyptian `tank-hunter’ squads came over the Suez Canal

lugging their RPGs and Sagger anti-tank missiles – these proved deadly to the

Israeli armour. One Egyptian unit knocked out eight Israeli M60s defending the

Bar-Lev line within the space of just ten minutes. Sergeant Ibrahim Abdel

Monein el Masri was the most successful tank killer, accounting for twenty-six

Israeli tanks, which gained him the Star of Sinai, Egypt’s highest bravery

award.

To protect the `tank-hunter’ teams from air attack, the

Egyptians were equipped with the man-portable SAM launcher known as the SA-7

Grail. This five-foot-long (148cm) shoulder-fired weapon provided low-altitude

air defence. The Israelis, though, were already familiar with the SA-7, as the

Egyptians had employed it extensively against Israeli jets during the War of

Attrition following the Six Day War. Israeli countermeasures greatly hampered

its already poor kill ratio. Nonetheless, combined with the Egyptian Army’s

other air defence missiles, the SA-7 for a while helped stop the Israeli Air

Force pressing home its attacks on the advancing Egyptian armoured columns.

The first Israeli counter-attacks by General Mendler’s 252nd

Armoured Ugda or division (consisting of the 14th, 401st Reserve and 460th

Reserve Armoured brigades) were easily beaten off with heavy losses, thanks to

the roaming Egyptian `tank-hunter’ squads. This was also in part due to a lack

of mechanised infantry support that left the Israeli armour vulnerable. By the

afternoon of 7 October 1973 the 252nd had lost some 200 of its 300 tanks.

Counter-attacks on 8 October were also repulsed, with further heavy losses

suffered by the 167th Armoured Division near Kantara, the Chinese Farm and

Fridan. The division’s three brigades were left with just 120 tanks by that

night. General Sharon’s 143rd Armoured Division then suffered smaller losses attacking

the Chinese Farm defences on the 9th.

The Israelis moved a reserve armoured division into Sinai on

8 October, tasking the 190th Brigade to counter-attack toward the Egyptian

pontoon bridges over the canal. They ran into determined Egyptian resistance

using the latest anti-tank guided weapons including the Sagger and the RPG-7.

The brigade was cut to pieces. In the meantime the Israelis had defeated the

Syrians by 9 October and easily fended off the supporting Iraqi and Jordanian

tanks. This left the IDF free to re-deploy their tanks against the Egyptians.

By 10 October the Egyptians had 75,000 men supported by 800

tanks deployed in the Sinai. In light of the Syrian defeat on the Golan Heights

both sides now prepared for the offensive. The Israelis decided to allow the

Egyptians to move forward first and beyond the cover of their SAMs. The

Egyptians struck on 14 October, but this was tank warfare that the Israelis

excelled at: their gunners pinned down the Egyptian attackers while other

forces struck the Egyptians in the flanks. By the end of the day the Egyptians

had lost up to 300 tanks and the survivors were soon in full retreat. The

following day the Israelis counter-attacked, crossing the canal in the

Deversoir area of Great Bitter Lake and then drove back the Egyptian 2nd Army

along the eastern bank.

On 15 October General Sharon, commanding three armoured and

two parachute brigades, located a gap between the Egyptian 2nd and 3rd armies

to the east of the Great Bitter Lake. He launched an armoured brigade in a

diversionary attack against the Egyptian 2nd Army in front of Ismailia. He sent

a second one in a southward loop to outflank them, with the aim of crossing the

canal just north of Great Bitter Lake. This was achieved, though initially Sharon

could only get forces across by pontoon ferry until bridges had been built the

following day.

Disastrously for the Egyptians they had no contingency plan

for the Israelis crossing the canal. They had expected the IDF to try and clear

the east bank with encircling operations, not cross the canal itself. It took

the Egyptians twenty-four hours to launch both the 2nd and 3rd corps into a

counter-attack against the neck of the Israeli penetration just northeast of

the Great Bitter Lake, in what became known as the `Battle of Chinese Farm’.

The fighting raged throughout the night of 16/17 October with heavy losses on

both sides. By the middle of the 17th Israeli armour was pouring over the

canal, sealing the fate of those Egyptian forces on the eastern bank.

By the time of the first ceasefire the IDF had secured a

foothold on the far bank of Great Bitter and Little Bitter lakes, i. e. west of

the Suez Canal. At the same time the Egyptian 2nd Army held a swathe of

territory east of the Suez Canal between Port Said to the north and Ismailia to

the south. South of the Lower Bitter Lake and beyond Suez City the Egyptian 3rd

Army held another strip. Despite the ceasefire both sides sought to improve

their positions. Crucially the IDF not only enlarged their bridgehead west of

the lakes but also drove south to Suez City and beyond to Adabiya on the Gulf

of Suez. Despite Egyptian counter-attacks this move trapped 20,000 men of the

Egyptian 3rd Army, cutting them off from drinking water, food and ammunition

supplies. In the area west of the canal the Egyptians had dug in many of their

elderly T-34 tanks hull-down in the sand – in the space of half a mile eighteen

were destroyed in their pits by the Israeli Air Force.

Having trapped the Egyptian 3rd Army, Israel finally agreed

to a ceasefire on 24 October. This left the Israelis occupying 600 square miles

of Egyptian soil west of the canal, encircling the 3rd Army and holding 9,000

prisoners. The ferocity of the Yom Kippur War is reflected in the casualties.

Egyptian and Syrian forces suffered 19,000 killed and 51,000 wounded. The

Israelis lost 606 officers and 6,900 men. Although Yom Kippur ended in a

resounding Israeli victory, the `Great Crossing’, as the Egyptians dubbed it,

was a major psychological victory for the Arabs. It had shown them that they

could take on the hitherto-invincible IDF and win.

The Golan Heights

Israeli defence minister Moshe Dayan was not blind to the

Arabs’ military buildup, both in the Sinai and on the Golan Heights, during the

early 1970s. He inspected the IDF forces on the Golan on 26 September 1973 and

warned them, `Stationed along the Syrian border are hundreds of Syrian tanks

and cannon within effective range, as well as an antiaircraft system of a

density similar to that of the Egyptians’ along the Suez Canal.’ While Dayan

put a brave face on things he also put the army on alert and quietly reinforced

the single, under-strength armoured brigade on the Golan, by redeploying the

normal garrison unit, the 7th Armoured Brigade, which had been drawn back to

armoured HQ at Beersheba.

It has been estimated that the first wave of the Syrian

assault involved up to 700 tanks: with 300 striking toward Kuneitra in the

middle of the Golan and the other 400 striking up the road from Sheikh Miskin

to Rafid to the south of Kuneitra; they were supported by three infantry

divisions. The intention was that the northern attack would cut the IDF’s Golan

defences in half by thrusting down the main Kuneitra-Naffak road. The southern

attack would then link up at Naffak as well as pushing south to El Al. In

principal it was a very sound plan.

The Golan was the fulcrum on which Israel’s fate rested – if

the IDF could not achieve victory there then they would not have the resources

to redeploy for a counter-attack against the Egyptians in the Sinai. While the

latter offered strategic depth of 125 miles, in which the IDF could conduct a

fighting withdrawal, the IDF faced defeat if ousted from the Golan. From the

frontline of the IDF’s forward defensive positions facing east to the cliffs

overlooking northern Israel the Heights are just seventeen miles deep. The IDF

had no option but to stand and fight where they stood. The only advantage the

IDF had on the Golan was they were masters of tank warfare and expert gunners. The

question was whether the Israelis would be able to knock out the Syrian tanks

fast enough to stop their positions being overrun.

Sitting on the Golan were two Israeli tank brigades, one of

them only at three-quarters strength. To the north, defending the narrowest

sector, was the 7th Armoured Brigade with about 100 tanks. The central and

southern sectors from Kuneitra to the Benot Jacov Bridge was held by the Shoam

Brigade with around seventy-five tanks. The brigade faced odds of five-to-one

and in some places even as high as twelve-to-one.

After the 1967 war Israel had occupied and improved the

Syrians’ existing triple defence lines that it had overrun; behind these lay

sixteen fortified Jewish settlements. It would take at least thirty hours to

mobilise reserves and get then up the road from Rosh Pina south-west of the

Benot Jacov Bridge over the river Jordan and up the ascent to the Golan. It is

not good tank country as visibility is poor. Mount Hermon is the only place

that gives a clear view of the Golan and all the way to Damascus. From there

the Israelis were able to watch the Syrian tanks marshalling on the plain

below. Mount Hermon would soon fall to a Syrian helicopter commando assault. In

the meantime the Syrian tanks were dug in to convince the IDF that they were

adopting a purely defensive posture.

West of the Golan Heights Israel’s Northern Command under

General Hofi was made up of the 146th armoured (9th, 19th, 20th and 70th

armoured brigades) and 240th armoured (79th and 17th armoured brigades)

divisions plus the 36th Mechanised Division (7th and 188th armoured brigades).

Syrian and allied armoured forces facing the Golan Heights

in October 1973, on paper at least, were quite formidable looking. They

consisted of the Syrian 1st and 3rd armoured divisions, each comprising two

tank brigades and a mechanised brigade. In addition the 68th, 47th and 46th

tank brigades supported the three Syrian infantry divisions allocated to the

attack.

Arab allied units consisted of the Iraqi 3rd Armoured Division

with the 6th and 12th tank brigades and the 8th Mechanised Brigade, along with

the Jordanian 3rd Armoured Division; the latter fielded the 40th Armoured

Brigade with the 2nd and 4th armoured regiments, the 1st Mechanised Battalion

and the 7th Self-propelled Artillery Regiment, and the 92nd Armoured Brigade

with the 12th and 13th armoured regiments, 3rd Mechanised Battalion and the

17th Self-propelled Artillery Regiment. Morocco also provided a mechanised

brigade and Saudi Arabia a mechanised regiment.

At 1400 hours on 6 October 1973 Syria threw its armoured and

infantry divisions, equipped with 1,200 tanks, into an operation that was

expected to drive the Israelis from the Golan Heights in the space of just two

days. To fend them off were the two Israeli brigades with 180 tanks. These

units brought precious time while Israeli reinforcements were rushed to the

front. What followed was a brutal slogging match as the two sides caught each

other head on. Remarkably two damaged Israeli Centurions held off about 150

Syrian T-55/T-62 tanks and during a thirty-hour tank engagement knocked out

over sixty tanks.

During the fighting in the `Valley of Tears’ the destruction

was terrible. The Syrian 7th Division and the Assad Republican Guard lost 260

tanks, along with well over 200 BMP armoured personnel carriers, BRDM light

armoured cars and bridge-layers. Of the Israelis’ 105 runners from the 7th

Armoured Brigade they had just seven operational tanks. Although the Syrians

broke through they lost 867 tanks to superior Israeli tactics and the timely

arrival of reinforcements.

By 9 October the Israelis had triumphed against the Syrians.

The Iraqi and Jordanian armour did not intervene until the second week of

fighting; the Israelis broke up a counterattack by the Iraqi 3rd Armoured

Division on 13 October; the latter performed fairly poorly, losing 140 tanks to

the Israelis.

Three days later the 40th Armoured Brigade from the

Jordanian 3rd Armoured Division ran into the Israelis and after losing twenty

tanks in two days of fighting took no further part in the battle. When the

fighting on the Golan finally came to the end it had cost the Syrians and their

allies a total of 1,200 tanks.

The Israeli Air Force learned the hard way in 1973 that

before all else they must neutralise enemy radar and SAM sites. In eighteen

days of fighting the Israeli Air Force suffered, by its usual standards,

appalling casualties – losing over 25 per cent of its combat aircraft, mainly

to radar-guided anti-aircraft artillery rather than missiles (the Arabs

accounted for 114 Israeli aircraft, of which the bulk were as a result of

ground fire). For any other air force in the region this would have been

crippling.

Just as importantly Egypt’s Soviet-supplied wired-guided

anti-tank missiles had shown how vulnerable tanks could be to tank-hunter

groups. The men of the Israeli armoured corps paid a heavy price for their

victory: 1,450 tank crew were killed in the Sinai campaign with another 3,143

wounded in action. The Israelis lost some 400 tanks, though many were later

repaired. This led the Israelis to develop the Blazer reactive armour system

(explosive blocks fitted to the outside of their tanks) and composite armour to

protect against the Arabs new anti-tank weapons.

The Israeli armoured corps lost almost 40 per cent of its

southern armoured groups in the first two days of the war, which highlighted

the need for vital infantry support and ultimately led to the Merkava main

battle tank being fitted with a rear troop bay. One of the most glaring deficiencies

of the Israeli armour was their lack of night-vision equipment (the Egyptian

and Syrian tanks had infra-red, including the British made Xenon infra-red

projector, giving them a serious advantage over the Israelis during the many

night encounters) and after 1973 they began acquiring image-intensification and

thermal imaging night-vision systems.

On the eve of the Yom Kippur war the Israelis fielded 540

M48A3 (with the upgraded 105mm gun) and M60A1 tanks. By the end of the fighting

they only had around 200 still operational. This was because of severe

vulnerability caused by the hydraulic fluid at the front of the turret, which

proved to be a major problem while fighting the Egyptians in the Sinai. The

rapid turret traverse system, if hit, tended to spray the flammable hydraulic

fluid into the tank. The losses were replaced with the Magach 5 (M48A5) and

Magach 6 (M60) upgraded during the 1970s.

Under the codename Operation Nickle Grass America airlifted

vital military supplies to the Israelis during the bitter and desperate

fighting. Key amongst these was artillery rounds and TOW and Maverick anti-tank

missiles. According to the US Defence Intelligence Agency, the latter accounted

for most of the Israeli tank kills. Fighter replacements, after the heavy

losses to the Egyptian air defences, totalling 76 aircraft were welcome. It was

this re-supply that emboldened the IDF to break through Egyptian defences on

the west side of the canal. In contrast, American tank replacements were not in

sufficient numbers to have any real bearing on the fighting. The airlift

delivered just twenty-nine tanks, but only four arrived before the ceasefire on

22 October 1973. Another twenty-five were delivered but this was after

hostilities had stopped.