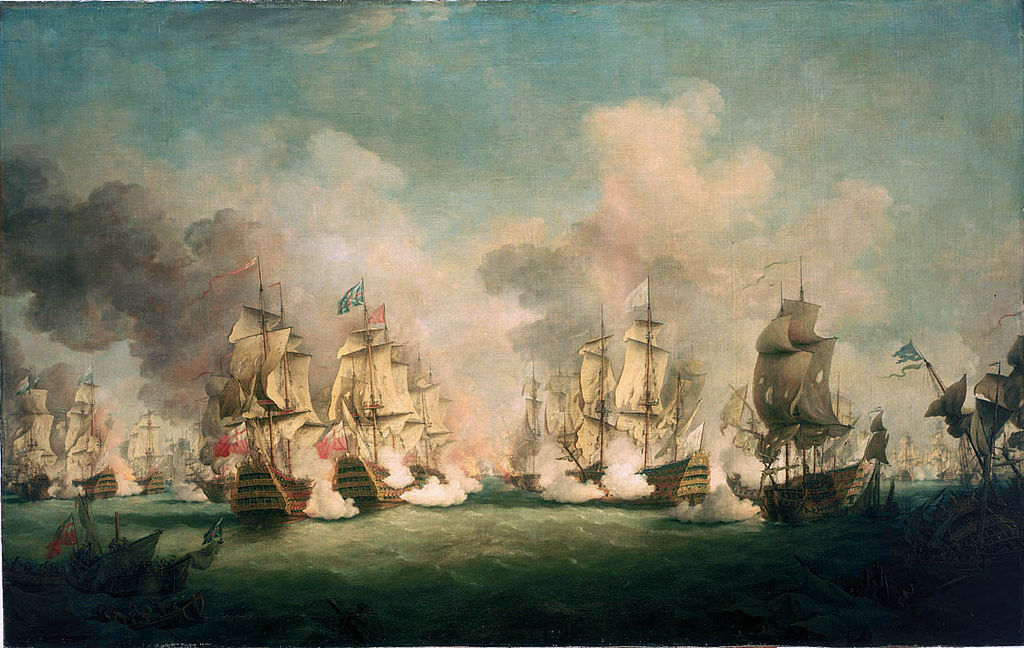

The battle-fleets with masses of ships and great weights of cannon dominate our vision of late seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century naval warfare just as mass infantry formations are central to our view of land warfare. But there was an equivalent to the light troops of the armies of this period. The great ships were clumsy, relatively slow, and could only undertake long journeys with great difficulty and careful preparation. In 1693 an Anglo-Dutch fleet, allied against Louis XIV of France, was ordered to escort through the Channel a convoy of merchant ships from both countries bound for Smyrna. The allies had recently won a substantial fleet action over the French at Barfleur-sur-Hogue in 1692, and this may have inspired the governments to order the departure of this convoy at short order. The great battle fleet, however, was short of provisions and accompanied its charges only beyond Brest. The French ambushed the convoy off Cape St Vincent, capturing or sinking ninety-two ships in a disaster which cost more than the total losses of the Great Fire of London in 1666. By the late 1690s the French realised that they could not match the building programmes of their Anglo-Dutch enemies and so could not challenge them in fleet actions. Instead they resorted to the guerre de course, war against commerce, which, as the Smyrna incident shows, could be highly effective. Privateer captains fitted out their ships at their own expense, though with government aid. Prizes, captured ships and cargoes, were divided between the state and the privateer captains. This stimulated the British to build cruisers, later called frigates, fast light ships which could take on privateers.

Seen from the twenty-first century, warfare in the

eighteenth century often appears stately, almost ritualistic. Armies in their

colourful uniforms were relatively small and moved slowly, often bogged down in

sieges of places now regarded as unimportant. Wars were waged for the ‘balance

of power in Europe’; this has often seemed a very abstract notion, and one

appropriately served by limited war. But Louis XIV’s ambitions to seize the Low

Countries and expand the frontiers of France were very threatening to the real

interests of many states which banded together in coalitions against her. The

result was a whole series of wars. The War of Devolution (1667–8), the Dutch

War (1672–8), the War of the Reunions (1683–4) and the Nine Years War (1688–97)

were succeeded by the War of the Spanish Succession. At times the fighting was

very intense: at Landen in 1693 there were 23,000 casualties which compares

with Malplaquet whose butcher’s bill of 33,000 shocked Europe in 1709.

The stakes were high. In the case of the Dutch War, Louis

clearly intended to extinguish Holland, which had frustrated his ambitions in

the War of Devolution. There was fighting in the West Indies and such was the

internal pressure in France that revolts broke out in Brittany and amongst the

Protestant Huguenots, which the Dutch sought to encourage. Louis’s seizure of

Philippsburg in 1688 prompted a Dutch coup in alliance with English opposition

forces which overthrew Louis’s friend and ally, the Catholic James II of

England (1685–8), and replaced him with the Dutch Stadtholder William of Orange

(1672–1702). In the resultant war there was fighting in the Netherlands,

Germany, Ireland, Spain, Italy, the Mediterranean, Canada and South America.

And civilian populations suffered badly. Year by year the French established

armies in western Germany, and while ‘contributions’ were less brutal than

ravaging, this may not have been evident to the suffering peasantry. In 1672–3

the French adopted a scorched earth policy to force the Dutch to surrender, and

in 1674 and 1688–89 they devastated the Rhine Palatinate to deny its resources

to the enemy. The warfare of the early eighteenth century was slow-moving, but

it was as destructive as warfare always is. Louis annexed substantial territory

in what had been the Spanish Netherlands and ‘rounded out’ the frontier elsewhere,

building modern fortresses to protect his gains. His success rested on

sustained warfare, a grinding attrition over long periods of time, made

possible by the growing wealth of the French monarchy.

Louis’s wars culminated in the War of the Spanish Succession

which was brought on by the death without heir of Charles II (1665–1701) of

Spain. His empire extended to most of Italy, the Spanish Netherlands, the

Americas and the Philippines. As a Hapsburg he was a member of the family which

ruled Austria, but he was also closely related to the French Bourbons. He

wanted his lands to pass intact to a single heir, and chose Louis XIV’s

grandson, Philip of Anjou. Although the will stipulated against it, this

bequest raised the prospect of an eventual union of the crowns of Spain and

France, and the creation of a gigantic superpower which would dominate the

whole continent. Louis did nothing to dispel this fear, precipitating a great

general war. Philip was accepted in Spain and Louis enjoyed the support of

Bavaria and some other minor German powers like Cologne which resented Hapsburg

domination. The duke of Savoy protected his Italian frontier against the

Austrians. Louis even encouraged Ferenc Rákóczi to lead a Hungarian uprising

against the Hapsburgs. The Hapsburg Emperor Leopold I (1658–1705) was at the

heart of the alliance against France and he drew in his wake most of the German

principalities. In 1701 he persuaded the Elector of Prussia to join by granting

him the title ‘King in Prussia’, while England and Holland were major allies.

This war exemplified early eighteenth-century warfare in

that it was dominated by fortifications. Large numbers of the soldiers on both

sides were absorbed in defending these strong-points. At heart they were

massively developed and strengthened versions of the trace italienne, mounting

huge numbers of heavy guns. Louis XIV’s great engineer, the marquis de Vauban,

is chiefly remembered for his skill in designing some of the most modern of

these along the French frontier. But his great contribution to war was the

systematisation of siege. At Maastricht in 1673 he surrounded the city with

zigzag lines from which trenches moved in to create yet more lines from which

the walls could be bombarded or assaulted. As long as the besieger prepared

well and fed his army, and could prevent relief, sieges now proceeded with

mathematical precision. If the garrison was determined the process was bloody.

Lille held out against Marlborough for four months before surrendering on

terms, having inflicted 14,000 casualties on his army. Assault was terrifying,

as a young officer remembered how he had stormed one of the breaches made by

the artillery:

I went up the ladder and when about halfway up I called

out ‘Here is the 94th!’ I was glad to see the men begin to mount … I believe

there were not many of our regiment up before me – at least I was up before the

commander of my company. I lost him at the heap of slain caused by the

grape-shot.

The line of confrontation between France and the coalition

lay through the Netherlands and down the Rhine, the most heavily fortified zone

in Europe. On the upper Rhine the imperial forces created the lines of

Stollhofen, penning in the French around Strasbourg, lest they use this as a

jumping-off point to attack south Germany and Austria. There were sieges and

battles, but they all failed to achieve decisive results. Then there was a

sudden flurry of spectacular movement. In 1703 the French general Villars

attacked Landau in the Stollhofen lines very late in the season, catching the

allies off guard, and subsequently defeated their poorly commanded relief

effort at Speyerbach. In conjunction with Max Emanuel of Bavaria, Villars

seized Ulm and Augsburg and threatened Vienna whose forces were distracted by

the Rákóczi revolt in Hungary and reduced by the needs of the fighting in

Italy. Villars imposed heavy ‘contributions’ on the German countryside to

supply his army, defraying 42 per cent of his costs, including 128,000 livres

in ransoms. Max Emanuel demanded a substantial slice of the ‘contributions’ and

their disagreements stymied further progress. Ultimately the French general was

replaced by Marsin.

Austria was clearly at risk and the English commander,

Marlborough, took 20,000 men and feinted towards the Moselle. On 19 May he

abruptly marched south, collecting allied forces en route and arriving at

Launsheim close to Ulm on 22 June. The crude rate of march of 7.5 miles per day

was not especially impressive and the average distance of 13 miles covered on

days of actual march corresponded to what ancient and medieval armies had

normally managed. What was impressive was that the force arrived in good shape

to fight, because Marlborough contracted with his agents, the brothers Medina,

to purchase food and threatened the ‘friendly’ rulers of the territories

through which he was passing with dire consequences if they did not help him.

By the standards of the age this was a lightning march made possible by careful

preparation, but the demands of speed meant that Marlborough had relatively few

guns. He therefore had to storm Donauwörth to obtain a bridge across the

Danube, suffering 5,000 casualties in the process and lacked artillery to

attack a fortress like Ulm. In fact he proceeded to ravage Bavaria in a brutal

effort to drive Max Emanuel out of the war. In response, Louis XIV dispatched

Marshal Tallard with a formidable French army, but although they made good

speed they were exhausted by the effort and harassed badly by German peasants

enraged by their ravaging.

On 12 August the allied and French armies faced one another

across the little river Nebel on the north bank of the Danube. Each army had

roughly 56,000 men, though the French possessed ninety guns to the allies’

sixty. The French thought a clash unlikely, with good reason. Battle was

chancy, the allied army was far from its bases and the key fortresses in the

area were all held by the Franco-Bavarians. Defeat, therefore, would have been

disastrous. This misreading of allied intentions probably explains why the

French and their allies deployed so badly, with Tallard’s purely French forces

around Blenheim near to the Danube on his right, and Marsin and the Elector far

to the left. Oberglau marked the junction of what were effectively two armies

barely linked together. Marlborough made a great thrust at the centre of the

enemy line. Some 14,000 Franco-Bavarian troops surrendered and perhaps as many

as 20,000 were killed or wounded. The allies suffered 13,000 losses. Such

losses are a testimony to the effectiveness of close-range musketry and massed

bayonets.

Blenheim was a decisive victory which ended the threat to

Vienna and brought all Germany over to the allies, but essentially it only

nullified a temporary French advantage, and the whole Franco-Spanish defensive

system along the Rhine and into Flanders remained. Marlborough was soon

re-immersed in attacking fortifications in Flanders where the French easily

held their own. In 1706, however, when Louis changed his strategy and ordered

his armies onto the offensive, Marlborough won a great victory at Ramillies and

scooped up a number of towns and cities, but was bogged down till September by

the formidable fortress of Dendermonde. In Italy, after initial French gains,

Prince Eugene relieved the siege of Turin and crushed the French army, forcing

evacuation of the Po plain, while the Catalan rebels against Philip of Spain

held out and an allied army threatened from Portugal. But nothing had broken

the French will to fight on and the coming years failed to produce any decisive

result, although Marlborough won a stunning victory at Oudenarde on 11 July

1708 which led to the capitulation of Lille after a long siege in December. In

1709 Marlborough scored another great victory, at Malplaquet, but at a cost of

enormous losses in the face of an able defence by Villars whose army suffered

much fewer losses and retired in good order. With military momentum lost,

political initiatives then took centre stage and by 1713 peace left Spain in

Bourbon hands and France virtually undiminished.

Louis XIV, despite losing many major battles, won the War of

the Spanish Succession, essentially because he was defending the status quo

established at its start. The warfare of this period resembled that of the

Hundred Years War in that it was a long-drawn-out contest of wills, spurred on

by occasional victories. In the absence of any means to destroy an enemy,

victory was a mirage. On land it could only be purchased by casualties which

exhausted the victor, and the defeated could repair to his fortifications. At

sea it was difficult to achieve a decisive result because fleets depended on

the wind and could as easily fly from battle as close for it. As a result war

slid into compromise, but it was the compromise of exhaustion, not of intent.

Our eye is taken by spectacular events like Blenheim and the

savage warfare in Flanders, but the sheer scale and intensity of the fighting

were staggering. In France there were persistent Protestant revolts, and the

famine of 1709–10 there caused terrible unrest and brought offensive actions to

a halt. In England, Louis tried to foment civil war in order to restore the

Stuart monarchy. Hungary rose against its Hapsburg rulers with French

encouragement, while Catalonia made a bid for independence from the Spanish

crown. Italy was ravaged by the clash of French and Austrians, and Portugal

wavered between France and the allies. Navies fought at sea and there was war

in the colonies. And appalling damage was inflicted. An estimated 235,000–400,000

seem to have died in fighting during the War of the Spanish Succession; that

does not take into account deaths by sickness, or civilian casualties direct

and indirect. On Louis’s death in 1715 it was revealed that the French state

owed 2.5 million livres. In no real sense was this limited war, except,

perhaps, for the British who, safe behind their navy, picked up colonies and

guarantees which profited them for the future.

European warfare in the eighteenth century was certainly not

just a formal parade-ground affair, and it was not static because war was

frequent and soldiers and political leaders reflected carefully on their ideas

and experiences. The Emperor of Austria, Charles VI (1711–40), had only a

daughter, Maria Theresa (1740–80), and the law provided that a woman could not

succeed to the throne. Charles persuaded the European powers to agree to her

succession by the Pragmatic Sanction of 1713, but when he actually died on 20

October 1740 most of the signatories reneged. Frederick the Great of Prussia

had inherited a standing army of 83,000 which could be mobilised quickly. On 16

December 1740 he invaded the rich province of Silesia which he had long

coveted; by the New Year he held most of it. This precipitated the War of

Austrian Succession (1740–48), in which Prussia, France and Spain allied

against Austria, Holland and Britain. This gave rise to the Anglo-French

conflicts of ‘King George’s War’ in North America and the First Carnatic War in

India. The settlement of 1748 confirmed Frederick’s possession of Silesia and

all Europe recognised the rise of a new military power based on the best

infantry in the continent.

Frederick the Great is the dominating figure in the military

history of the mid-eighteenth century. Yet in his first experience of battle,

at Mollwitz on 10 April 1741, he fled the field when things appeared to be

going badly. All was saved by his senior officers, and above all by the

discipline of the Prussian infantry. In the words of an Austrian officer

captured in the battle: ‘It did not appear to be infantry that was marching

towards them, but moving walls.‘ The price was high – the Prussians lost 4,850

men – some 300 more than the Austrians. Frederick was truly a child of the

Enlightenment, the great intellectual current then sweeping Europe which

recognised ‘reason’ as the great source of power and authority. Accordingly, in

his General Principles of War published in 1753, he tried to systematise what

he had learned. He understood the limitations of contemporary infantry volley

fire. The king’s preference was for skilful manoeuvre and fast and relentless

movement which he thought would overwhelm his enemies. He insisted on infantry

advancing in very close order with muskets on the shoulder until the very last

moment. At his insistence Prussian troops adopted cadenced marching to keep

them in step and he developed very complex drills to bring his forces quickly

from line of march into line of battle. In battle the enemy would be softened

up by artillery preparation and infantry were equipped with light 3-pounder infantry

cannon to pave the way for the assault, but it was shock and cold steel which

would destroy the enemy, and troops were urged not to hesitate but to press on

until victory was complete. His cavalry were also drilled to close order and

expected to charge home. He had plenty of opportunity to test these ideas in

the wars that lay ahead.

Austria feared Prussia as a dangerous adversary in Germany

and formed an alliance with France and Russia whose rulers had ambitions to

acquire Poland which Frederick was certain to contest. English rivalry with

France in North America was becoming acute. The French claimed the Mississippi,

precipitating fighting in Ohio in 1754, and this was followed by their

construction of forts in western Pennsylvania. For this reason the English

backed Prussia in the Seven Years War of 1756–63. The Austrian commanders had

recognised Frederick’s fondness for rapid movement and direct assault with cold

steel. At Lobositz on 1 October 1756 Frederick attacked an Austrian army in

broken country where their Croatian irregulars inflicted heavy casualties

before his infantry drove the Austrians into an orderly retreat. In the

following year at Prague on 6 May Frederick threw his Prussians against a

strongly entrenched Austrian army and suffered 14,000 Prussian dead. At Kolin

on 18 June he again attacked the Austrians in a prepared position. His infantry

were harassed by the Croatians, disrupting their assault on the Austrians who

won an important victory, forcing Frederick to retreat from Prague. In each

case the Austrians deployed their firepower against Frederick’s well-known

predilection for frontal assault. But at Leuthen on 5 December 1757 Frederick

engaged on much more open ground, manoeuvring quickly to strike the enemy where

least expected, but his infantry now relied far more on firepower to win a

famous victory and he concentrated his artillery, hitherto somewhat ignored,

against the Austrian infantry.

Frederick conceived of horse-artillery – light cannon and

their caissons of shot harnessed to strong horse-teams, with the gunners riding

alongside – as a means of weakening enemy infantry who were an obstacle to the

fast and aggressive movement which he wanted from his cavalry. At the siege of

Schweidnitz in June 1762 he deployed his cannon carefully, with the very latest

howitzers firing explosive shells. His infantry then worked their way into the

Austrian positions using the ground skilfully. He was always impatient of

engineers, partly because in the open spaces of Central Europe fortresses were

much less common than in the west. But at Bunzelwitz in 1761, faced with an

overwhelming challenge from Austrian and Russian armies, Frederick was happy to

resort to a well-fortified camp. Both Frederick and his enemies learned from

experience. As more powers engaged, war grew in scale and became more intense.

At Zorndorf in August 1758 Frederick checked the Russian invasion of his lands,

but at a cost of 12,000 casualties – the enemy endured 18,000. Armies were

increasing in size and Frederick always suffered from a manpower shortage. By

1777 his army was not far short of 200,000, over double the number he had

inherited in 1740.

The intense warfare of the eighteenth century produced a new

emphasis on the training of officers. Prussia established the Berlin Cadet

Corps in 1717 for officer training. The French School of Engineers was founded

at Mezières in 1749, and the following year a similar institution for the

artillery appeared. The École Royale Militaire, where Napoleon would be

educated, was founded in Paris in 1750. In Austria the Wiener Neustadt Military

Academy served the same function while the Russian Cadet Corps had been founded

in 1731, and subsequently a number of specialist academies were created. In

England the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich opened in 1741. This all owed

something to the Enlightenment which was to influence Frederick the Great’s

General Principles of War, but the practical needs of war really drove the

trend: calculating artillery fire and siege-works, the difficulties of

controlling large armies, now regularly of the order of 60,000. War was

becoming increasingly complex and educating officers was therefore vital.

The rise of a more educated officer corps raised the

intellectual level of debate on war. France had done badly during the Seven

Years War, losing her overseas empire to Britain, and seeing her army defeated

by the Prussians at Rossbach on 5 November 1757. As a result, a series of

reforms was introduced and vigorous discussion was encouraged. Entry to the officer

corps was restricted to nobles; they were very numerous in France and many of

them were poor, so this measure helped to bind them to the crown. The abolition

of purchase of commissions offered them better prospects of promotion. The

staff, responsible for the organisation of war, was strengthened. French

commanders debated the value of attack in column, which was quicker than

deploying into line and easier to control. Their distinguished soldier and

military theorist, Jacques Antoine Hippolyte, comte de Guibert (1743–90),

advocated rapid movement and suggested avoiding siege by masking fortresses. He

thought that supply trains could be lightened and more emphasis placed on

living off the country in the interests of speed.

On the battlefield Guibert favoured experimentation with

light troops, even equipping some with rifles which had greater range and

accuracy than muskets so that they could harass the enemy line and pick off

officers. His greatest innovation, implemented after 1766, was to develop a system

whereby troops could deploy quickly for battle as they marched towards the

enemy. In addition he recommended that on the offensive a line of skirmishers

should be thrown forward to prepare the way for an ordre mixte with formations

attacking in column (usually battalions split into company columns) or in line,

as circumstances suggested. Such thinking about tactics and organisation was by

no means confined to the French. The British lined their men up in a double

rank and fired by platoon, thus a battalion delivered rolling fire across its

front from the moment the enemy came into range. During the later stages of the

Seven Years War, as armies became bigger and more difficult to control, the

Austrians seem to have experimented with very large sub-units of all arms led

by senior officers which could march and fight independently, but when

necessary combine on the battlefield.

Traditionally, because artillery was expensive, guns were

made 12 feet long so that if used in fortresses the muzzle would project and

the blast would not damage the masonry. This, of course, made them very heavy

and clumsy in the field. Frederick the Great’s horse-artillery were shorter and

had lighter bronze guns whose gunners rode into action to break up enemy

formations. In 1776 Gribeauval became French inspector of artillery; he

demanded that a regular corps of gunners be instituted, and he standardised

calibres. Under his aegis, an infrastructure of state-owned arsenals was

developed with their own boring machines. Hitherto cannon had been cast around

a clay core which was cut out when the metal had cooled. This produced erratic

bores, so that cannonballs could not be made to fit tightly. Boring made

calibres much more consistent so that ammunition could be standardised. Under

the Gribeauval system there was a sharp distinction between the lighter bronze

guns for field use and heavier weapons for fortress and siege.

Although European thinking was dominated by the full frontal

collision of regular infantry masses hardened to the ordeal of battle and siege

by discipline, Europeans knew very well what they called ‘little war’ (petite

guerre), a name which embraced anything outside the mainstream. The

Austro–Ottoman frontier saw constant raiding, and the ‘Croats’ and Hussars who

waged it were starting to contribute to the more fluid tactics evident in

Europe in the second half of the eighteenth century. In all major campaigns

light forces of cavalry and infantry skirmished; this was the inevitable

accompaniment of ravaging and levying ‘contributions.’ In addition, regular

armies maintained light forces whose task was to harass the enemy. In 1745 at

Fontenoy Marshal de Saxe employed sharpshooters who did great harm to the

attacking British and allied forces. During the colonial wars in the dense

forests and wastes of North America, both the British and the French employed

native tribes to harass their enemies. Famously, a Franco-Indian force ambushed

and killed the British General Braddock at the battle of the Monongahela in

1755. In the forest-steppe the Russians advanced by raiding, desisting only

when the small native tribes agreed to pay tribute and obey them. Gradually a

thin network of forts established Russian dominion over a vast area, but the

conquest was very much driven by local initiatives, though supplied with modern

weapons and backed, on an occasional basis, by Russian troops. Massacre and the

threat of massacre were the methods of both sides, but it was the growth of the

Russian population which drove the expansion, until they met Chinese

imperialism advancing from the other end of Asia.

In the eighteenth century popular insurgency, people’s war,

was uncommon in Europe. However, there is a myth that the American

Revolutionary War was won by patriots rallying to their militias in a people’s

war. This was certainly a broadly based rebellion against British rule. In 1776

the thirteen British colonies in North America revolted against the crown.

Notable amongst their many grievances was discontent at taxation levied by

London to cover some of the costs of protecting the colonies and the anger of

the colonial elite at London’s decision to halt westward colonisation beyond

the Appalachian Mountains. Open rebellion began in 1776, but became serious

when the Americans isolated Burgoyne’s small army at Saratoga in 1777,

provoking France, Spain and Holland to intervene. Thus a colonial dispute

became a worldwide war. But far from finding colonials anxious to rally to

their cause, the Revolutionary leaders had great difficulty in recruiting troops

at all. Washington had few illusions about the colonial militias. Indeed, he

would probably have agreed with Clausewitz: ‘Insurgent actions are similar in

character to all others fought by second-rate troops: they start out full of

vigor and enthusiasm but there is little level-headedness and tenacity in the

long-run.‘ His Continental Army of regulars was never really able to fight the

British on equal terms, but as long as it existed it gave hope to convinced

supporters, rallied the doubtful and served to threaten the hostile. But in the

Carolinas campaign of 1780–81 irregular warfare was decisive.

The British, with their increasing distractions elsewhere in

the world, could only deploy quite a small army, which made the reconquest of

the huge area of the colonies very difficult. One way in which they multiplied

the effectiveness of their troops was to use their command of the sea. In 1780

they seized the ports of Savannah and Charleston, and their commander,

Cornwallis, shipped in troops and supplies with which to rally the loyalists of

the Carolinas and thence to penetrate Virginia. At Camden, on 16 August 1780,

he defeated General Gates whose regulars fought well but were deserted by the

local militia. However, the British threw away the fruits of victory by

scattering their forces to rally the loyalists, and the new American commander,

Nathanael Greene, with inferior forces, was happy to engage in guerrilla

warfare which became more and more savage, polarising support. When Cornwallis

tried to advance northwards, Greene’s irregulars harassed the British in

support of his few regulars. They fought delaying actions which ultimately made

the British advance impossible to sustain.

There were clear signs that the new developments in Europe

were changing the balance of power hitherto so favourable to the steppe

empires. Nomad warfare, based on speed and light weaponry, did not foster the

development of gunpowder weapons. However, the peoples who created the steppe

empires had always shown remarkable adaptability. Ottoman armies in the

sixteenth century established a real lead in weapons and organisation over

their western neighbours, while the Manchu eagerly took up gunpowder in their

conquest of China. India produced magnificent firearms. There was no inherent

reason why these great empires should not respond to the European challenge.

That they failed was due to the chance factor that from the second half of the

eighteenth century, for very different reasons, all of them were going into

political decline.

The Ottoman standing army was formidable: by 1670 there were

about 50,000 janissaries, 14,000 regular cavalry and 8,000 men in the artillery

corps. The system of supply was far in advance of any army in Europe. But the

Ottomans were challenged by Austria in the Danube valley and the Balkans, by

Persia in the east and by Russia on the southern steppe. Their decisive

weakness was the decline of the janissaries. By the end of the sixteenth

century they had become a praetorian guard, and they overthrew the sultan Osman

II (1617–22) when he proposed to replace them. By the eighteenth century they

were becoming demilitarised. To save on cost the Ottomans permitted janissaries

to undertake civilian work, which gradually dominated their lives. An

increasingly small percentage of them were ever mobilised for war, but they

were all tax-exempt in respect of their ‘military’ status. As a result the

janissaries became political soldiers whose only military value was ceremonial,

but their integration into the political factions at the court made it

impossible to destroy them or to reduce their privileges even though their

nominal numbers were increasing. Some janissaries were permitted to acquire

military lands (timars) in the provinces to where they and other gentry increasingly

diverted funds from the central government. The decay of the janissaries forced

the sultans to raise new infantry and cavalry regiments, but because of the

reduction in central income and the burden of paying the janissaries, the new

troops did not form a standing force, so that increasingly the empire was

dependent on raw and half-trained soldiery. The artillery corps also suffered

from under-investment so that it was unable to modernise. These disturbing

trends took some time to become apparent and so great was the Ottoman lead in

military organisation that in 1711 they routed Peter the Great’s army at the

Pruth, and as late as 1739 recovered Belgrade from the Austrians and threw back

a Russian advance towards the Black Sea, forcing them to abandon their new

Black Sea fleet and its bases.

But the decay of the janissaries and the under-investment in

artillery weakened the Ottoman army, while the Russians and the Austrians were

learning from the European wars. In 1770 a Russian army of about 40,000 destroyed

over 100,000 Ottomans at the battle of Kartal and the ensuing treaty of Küçük

Kaynarca ratified the Russian advance to the Black Sea and the permanent

subjugation of the Tatars. By 1791 Austria controlled Belgrade and the Russians

were in Bucharest. As a result, in 1792 the Sultan devised his ‘New Order’

(Nizam-i), bringing in French soldiers to train new regiments on the European

model. The janissary opposition was supported by popular dislike of new taxes

to pay for the military reforms and by provincial resentments which sparked

local revolts. By 1797, however, the French held the Ionian islands and in 1798

Napoleon invaded Egypt, curtailing efforts at military reform. England and

France then proceeded to dispute control of Egypt and the eastern Mediterranean

with little reference to its nominal ruler at Constantinople. Such was the

price of ‘asymmetry’, failure to keep up with the European arms race.

In India the Mughals, another steppe power, declined sharply

after the death of Aurangzeb in 1707. He had rejected the policy of tolerance

towards the Hindu majority, and the strength of Islamic fundamentalism

embittered tensions at the courts of his successors who were in any case much

less capable men, creating widespread discontent. In 1739 Nadir Shah of Persia

sacked Delhi with an immense slaughter and in 1756 Ahmad Shah Abdali of

Afghanistan repeated the performance. Within India there were plenty of

possible successor states, notably the Maratha Confederacy, the Sikh

Confederacy and Bengal which had long enjoyed good government under a line of

independent nawabs (governors); in the south, Mysore had great potential.

Amongst the European trading companies the British were the most powerful with

outposts at Bombay, Madras and Calcutta. They were, however, rivalled by the

French with stations at Chandannagar and Pondicherry, while the Portuguese and

Dutch also had enclaves. All these companies had private armies backed up by

fleets, but a strong power could have played them off against one another. What

was lacking was just such a powerful local authority, and after the Seven Years

War the British were much stronger than the French. Marathas, and Sikhs, could

be militarily dangerous, but they were never really united and were quite

distinct from Muslim Mysore. The British, by contrast, displayed a solidarity

which impressed locals.

And they had a powerful motive for intervention. The East

India Company had very high costs which often exceeded income. As Mughal power

declined, the acquisition of jagirs, assignments of district revenues, was

becoming a major and highly profitable business. So grabbing the right to

collect taxes was an obvious path to riches. In 1756 the Nawab of Bengal

quarrelled with the British and seized Calcutta: many of his British prisoners,

including women and children, were imprisoned in a badly overcrowded dungeon

and perished in what became known as the Black Hole of Calcutta. The British

under Clive quickly reconquered Calcutta, and then at Plassey on 23 June 1757

their army of 3,000 faced the Nawab with 50,000. Clive bribed many of the

Nawab’s supporters so that the army melted away, enabling the Company to

appoint a puppet ruler. Of Clive’s troops, over 2,000 were local soldiers or

sepoys and only about 1,000, including the gunners, were Europeans. At Buxar in

1764 a Company army of 7,000 with less than 1,000 British, triumphed over

30,000 enemies because, according to their commander, Hector Munro, they had

‘regular discipline and strict obedience to orders’. By 1773 the British had

taken over as rulers of Bengal and a number of other small states. This was not

a merely military triumph; many of the local notables favoured the stability of

British rule, but the recruitment of the local soldiery, and their training in

modern methods of war, was the prerequisite for success.

The Indian powers were keenly aware of the need to develop

comparable discipline and methods, and as a result the British suffered many

setbacks in their path to empire. It took four wars lasting until 1804 to subdue

Mysore, while the three Maratha wars ended only in 1818. The Sikhs under Ranjit

Singh created a powerful empire of the Punjab centred on Lahore. Their army was

trained and officered by experienced French soldiers and equipped with modern

artillery which hitherto had largely been a British monopoly. Succession

disputes on Ranjit’s death in 1839 opened the way for British intervention, but

it was only after two costly wars that the Sikhs were finally annexed in 1849.

The British domination of India owed much to skilful diplomacy, which resulted

in a network of princely states whose rulers agreed to collaborate. The

merchants of the Indian cities came to see the Company as a force for

stability. The multiplicity of states in eighteenth-century India had created a

great market for soldiers, and the Company could offer well-paid and successful

service, in effect cornering the market, to create a powerful sepoy army.

British dominance rested on victory brought about by successful military

methods. The surging armies of light cavalry which had so often been the key to

victory in the northern plains were replaced by disciplined lines of infantry

supported by artillery and smaller cavalry units. The European way of war had

clearly displaced that of the steppe people. The native powers, despite their

different culture, espoused these new methods enthusiastically, but Indian

political units proved to be fissiparous and no single one of them was quite

strong enough quite consistently enough to survive. This was not a case of

‘asymmetry’ in the military sense, but of political weakness.