The Peloponnesian War ended in 404 and closed out the fifth

century with a surprise attack. Lysander, the Spartan, tricked the Athenians at

Aegospotami, by attacking their vessels at a regular hour and then calling off

his fleet. Once this had become an established procedure, the Athenians dropped

their guard after the Spartans dispersed. Then, when most of the Athenians had

scattered according to their usual pattern, he returned, attacked and slew the

rest, and captured all their vessels. The fourth century was thus ushered in

with the defeat of the Athenian Empire and a Spartan hegemony that took its

place and lasted until the Battle of Leuctra in 371. Sparta found itself

engulfed in the so-called Corinthian war from 395 until 387 against a coalition

of four allied states: Thebes, Athens, Corinth and Argos, which were initially

backed by Persia. Then the Boeotian or Theban war broke out in 378 as the

result of a revolt in Thebes against Sparta; the war would last six years.

There was obviously no shortage of warfare in the fourth

century, and all sides continued to fight with hoplites, but the conditions of

military life were slowly changing. Gone was the era of short military

campaigns that took place only during the summer after the harvest. Cities were

now attacked by night, fighting took place year-round, and atrocities were

committed against civilians. The prolongation of campaigns and a change in

tactics set the stage for the professionalisation of Greek armies. Whereas

hoplite warfare had not necessarily called for very elaborate training, the use

of missiles and the tactics of staging ambushes required training at a higher

technical level. When light-armed troops were utilised everything depended upon

movement. Rapid changes of position, sudden strikes, speedy retreats and

ambushes were all operations that needed to be carefully prepared with accurate

intelligence. Because such operations had to be well directed and executed with

speed and determination, it could mean training one’s own troops or hiring

well-trained mercenaries.

The change from militiamen to paid fighters meant a change

from amateurs to professional soldiers. Foreign mercenaries were expensive and

could not usually be hired in large numbers, but citizens could be recruited

and trained to perform the same specialised functions provided by foreign,

light-armed mercenaries. Athens’ overseas expeditions in the fourth century

were all carried out by mercenaries.

Light-Armed Troops and Peltasts

An increasingly important role was played by light-armed

troops in the fourth century, and they became a significant factor in the

conduct and the outcome of battles. Although hoplites mattered most in set

battle on a large scale, war on land now had a place for other arms and other methods

than those of the hoplite phalanx. Smaller tactical units gave a new

manoeuvrability that had been impossible in traditional hoplite lines. These

new troops became effective in gaining tactical advantage, usually through a

sudden, surprise assault. Small striking forces became especially important in

fifth-column operations.

There were several types of light troops, the most common

being archers, slingers and peltast-javelin men.8 The peltasts became the most

effective of the light-armed troops. Peltasts were a sort of mean between the

extremes of heavy and light-armed men. They had all the mobility of light-armed

troops, and yet sufficient offensive and defensive armour to cope, with a fair

amount of success, with small bodies of hoplite troops (i.e. those not in

set-piece battles). Using peltasts would increase the ability of Greek armies

to stage surprise attacks and ambushes. The name peltast comes from the fact

that they were armed with a pelte (Thracian shield). In place of a dagger, they

might also carry a kind of scimitar, a curved sabre known as a machaira, which

could be used to deal slashing blows. Peltasts were not much help in stopping a

hoplite force head on; their main use was to protect the flanks of an advancing

hoplite army against attacks from the light-armed troops of the enemy. The

majority of Greek states had an organised body of light-armed troops. Athens

was an exception until this was changed by commanders such as Iphicrates and

Chabrias.

Although their weapons might seem simple, these light troops

were specialist soldiers. Their way of fighting entailed a higher degree of

specialisation than the relatively straightforward, spear-and-shield techniques

of hoplites fighting in formation. The accurate use of missile weapons was a skill

acquired and maintained only by regular and constant practice. For this reason,

light-armed troops tended to be professionals. At first, they were foreign

mercenaries recruited in Thrace, Crete and Rhodes; later, they were natives

recruited locally from city-states. Athens was the first to transform some of

the poorer citizens into light troops.

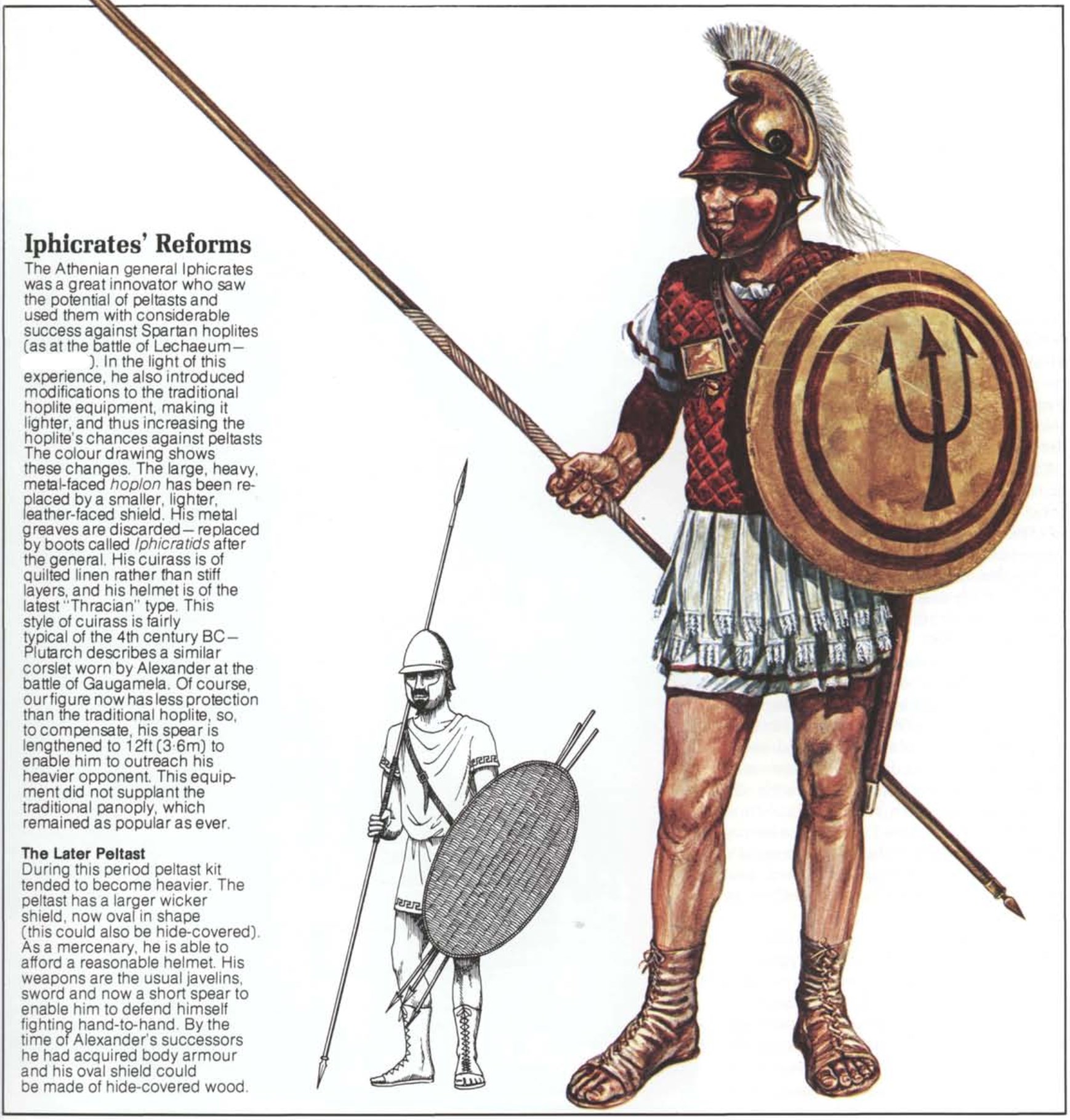

The Athenian general Iphicrates is credited by two ancient

sources – Diodorus and Cornelius Nepos – with reforming the equipment of his

hoplites. These military reforms have long been the subject of scholarly

debate, but what is clear is that they were much better equipped to stage

ambushes. Iphicrates did away with the large hoplite shield – the aspis – and

replaced it with the smaller pelta. He also lengthened the sword (xiphous) and

the spear (doratos). Of course, there were peltasts in use long before this

time in other regions of Greece, but now the reform was coming to Athens.

The defeat of the Athenian hoplites by light-armed cavalry

and peltasts at Spartolus, the successful defence by Acarnanian slingers of

Stratus against Peloponnesian hoplites, or the destruction of Ambraciot

hoplites by Amphilochian light-armed, not only reinforced the lessons learned

from the experience in Aetolia and Sphacteria but also carried them still

further. From the last phases of the Peloponnesian war and, continuing into the

fourth century, armies began to contain significantly higher numbers of

specialised troops than Classical ones had fielded. This included the growth of

a corps of archers, the addition of light-armed troops, the rise of mercenary

troops recruited largely from abroad, and the development of cavalry.

Generalisations about mercenary service can be misleading.

It is commonly assumed that mercenary soldiers did not become a significant

factor of Greek social and political history before the fourth century. In

fact, however, Greek mercenary soldiers had been serving in armies of southeast

Mediterranean powers since the Archaic Age. The reasons for soldiers becoming

mercenaries and their terms of service vary. In Crete, for example, one would

cite demographic developments and military traditions as well as socio-economic

crisis. Another accusation that dogged military operations was that the

systematic use of mercenaries encouraged a selfish inertness at home, a

dangerous licentiousness in the free companies abroad, and that it diverted the

energies of the ablest citizens from patriotic objects to the baser pursuit of

plunder and military fame. The fact is, however, that soldiers did not take up

this line of work because it was so lucrative. Service in places such as Persia

and Egypt might be lucrative, but service in Greece proper was not. Soldiers in

the fourth century accepted military service knowing that there was no money in

it for them unless they looted, stole or won booty.

Hoplite Armour and Hamippoi

Another military innovation that occurred in the fourth

century was the lightening of the hoplite panoply. Some hoplites were still

sporting extensive metal armour in the mid-fourth century, but the overall

trend of the Classical period seems to have been a progressive lightening of

hoplite armour. This made hoplites more mobile and thus better able to cope

with the challenges of difficult terrain, enemy skirmishers and ambushes.

Lighter panoplies were also cheaper. Konrad Kinzel suggests that this enabled

more citizens to equip themselves as hoplites and enjoy the attendant political

status that went with this type of fighting. But were these troops really

hoplites any more? Nick Sekunda also describes the shift in the use of armour

plate in the late fifth century. He seems to think that armour all but

disappeared as the Spartans were depicted wearing only a pilos helmet and

tunic, no cuirass, greaves, etc. and Boeotian hoplites were all but naked. Does

this indicate a change in battlefield tactics? The availability of materials?

And were these soldiers still considered ‘hoplites’, i.e. heavy infantry? It

certainly contributed to them being more mobile and able to counter attacks by

light-armed soldiers.

Another military innovation of the fourth century was the

introduction of hamippoi, a type of light-infantry corps that ran behind

cavalrymen. The hamippoi were trained to fight alongside the cavalrymen. They

would go into battle holding on to the tails and manes of the cavalry horses.

Hamippoi were particularly useful in a straight cavalry fight, where they would

hack at the enemy horsemen. One of their signature manoeuvres was to slip

underneath the enemy horse and rip its belly open with a dagger. This certainly

suggests that service in the hamippoi was not for the faint-hearted. In his

pamphlet On the Duties of the Hipparch, Xenophon recommends that the Athenians

raise a corps of such men from among the exiles and other foreigners in Athens,

who had special reason to be bitter against the enemy. Xenophon saw their value

as being able to deliver a surprise as he points out that they could be hidden

among and behind taller mounted troops.

Hamippoi were first mentioned serving in the forces of the

Syracusan tyrant Gelon, where his 2,000 cavalry were accompanied by an equal

number of hippodromoi psiloi or psiloi who run alongside the cavalry. Hamippoi

are found in the Boeotian army during the Peloponnesian war. When the Spartan

army was reorganised some time after the Battle of Mantinea in 418, the 600

skiritai were not folded into the ranks of the morai but were converted into

the hamippoi and fought alongside the 600 cavalry.

In short, as the fifth century progressed into the fourth,

the trend was to lighten the armour of the hoplites and add soldiers from the

lower classes, who could perform various new duties that required greater speed

and manoeuvrability. This made ambushing more difficult and less likely if each

side had mobile troops that could improvise.

The Generals in the Fourth Century

The need to develop specialised, light-armed troops

encouraged the rise of professional generalship in the fourth century. The

proper handling of such troops required something more than amateur leadership.

Fourth-century generals had to recruit different types of soldiers, who used

different types of weapons and tactics. W. K. Pritchett dedicates a chapter of

the second volume of his comprehensive work, The Greek State at War, to this

new breed of general. Their careers were made possible by the changing

political and military circumstances, and new operating conditions dictated

some new fighting techniques. The military commanders in the late fifth and

early fourth centuries had to conduct military operations more and more

independently, relying on their own skill and talent. They developed

increasingly strong ties with their army rather than just their polis. The

independence of fourth-century commanders was a function of long-term service

abroad and of operating independently of their home authorities. How much

freedom they enjoyed in the field can probably never be precisely determined,

but those who were elected or appointed to office by the larger city-states

seem to have discharged their functions with as much loyalty as similar

officials in the fifth century.

Another motivation for the increased use of novel techniques

and stratagems was that fourth-century military forces were sent out without

being provided with money. The generals were expected to raise funds by

plunder, by contributions from allies or even by foreign service. They and

their troops seem to have had unlimited permission to plunder the enemy’s

country. In the fifth century, mercenaries had been dismissed when the state

lacked funds, but conditions had greatly changed in the fourth century. A great

number of the stratagems that are collected in Polyaenus and assigned to

Athenian generals of the fourth century have to do with the raising of money to

pay their troops. Six of the stratagems preserved in Polyaenus on Jason of

Pherae, for example, deal with means for securing funds.

Even with these new troops, staging an ambush was no easier

to accomplish in the fourth century than it was in the fifth. Naturally, it was

best done with soldiers who were trained by their leaders in the skills needed

for such operations. This is where the light-armed troops, especially peltasts,

excelled. Light-armed troops, unlike hoplites, were trained to be highly

responsive and flexible. They had to be able to close with the enemy and kill

quickly. Light infantrymen could be used to destroy the enemy on his own

ground, make the best of initiative, stealth and surprise, infiltration, ambush

and night operations. Iphicrates trained his light-armed troops by staging fake

ambushes, fake assaults, fake panics and fake desertions so his men would be

ready if the real thing happened. Light infantrymen were not tacticians; they

could not respond mechanically to a set of conditions on a battlefield with a

pre-determined action like a phalanx. Whoever led the ambush had to know how to

use initiative, understand intent, take independent action, analyse the field

of operations, collect intelligence and make rapid decisions. Initiative meant

bold action and often involved risks. Initiative by the tactical leader may

have been independent of what higher commanders wanted done to the enemy. The

men such leaders worked with were soldiers trained to fend for themselves

through hardship and risk in hostile, uncompromising terrain. Such operations

built a greater degree of teamwork and skill than other types of infantry

formations as a result of the stress put on adaptability, close-combat skills

and independent action.

Fourth-Century Ambush

Greek literature in the fourth century contains much more

information on ambush than its fifth-century counterpart. Even didactic works

such as Xenophon’s Cyropaedia, while wholly removed from the context of real

events, give lessons about commanding a Greek army. The ambush against the

forces of Gadatas42 is a classic use of clandestine communications and the

laying of an ambush among a cluster of small villages. We can also see a

classic deception operation, where soldiers are arrayed along with the baggage

train and the women to make their force seem larger than it is. Any enemy

attack would have to make a wider circuit around them and thereby thin out

their own lines.

We cannot always be sure of the dates or even the historicity

of certain stratagems, but they all seem to describe generic situations that

crop up again and again. One of the most common ways to stage an ambush, for

example, was to attack an army on the march. Polyaenus gives an undated example

of the detection of such an ambush. While leading his army, Tissamenus saw many

birds flying above a particular place, but not settling on the ground, and he

concluded that they shrank from settling because they feared men lying in

ambush. After investigating the spot, he attacked and cut down the Ionians who

were waiting in ambush. This is a much repeated story, with several Roman

commanders using the same tactic.

Another piece of good advice was to be ready for an ambush

whether you were expecting one or not. Polyaenus tells a story about Arxilaidas

the Laconian who, around 370/69, was about to travel a suspicious road with his

army. Pretending he had advance intelligence which he did not, he ordered them

to advance prepared for battle because the enemy lay in ambush. But by chance a

large ambush was discovered. He attacked first and easily killed all those in

ambush, outsmarting them by his advance preparations.

Playing on the known habits of barbarian tribes was another

common practice. Polyaenus relates several stratagems used by Clerachus against

the Thracians, which presumably date from a time just prior to his entering the

service of Cyrus. All illustrate the frequency of Thracian nocturnal attacks.

This practice, according to Polyaenus, enabled Clearchus the Spartan to set an

ambush for one of the local Thracian tribes, the Thrynians. He withdrew a

little distance with a number of soldiers, and ordered them to hit their

shields, as was the Thracian habit, putting all the Greeks in camp on alert.

When the Thracians attacked, they expected to find everything in camp peaceful

and quiet, but the Greeks were ready for them and they were beaten off with

severe losses. When the Thracians sent envoys to negotiate a peace, Clearchus

had the bodies of a few dead Thracians cut up and strung from trees. When the

envoys asked about the meaning of the spectacle, they were told that a meal for

Clearchus was being prepared! Such antics as these caused people to question

the ethical aspects of Clearchus’ conduct, but his military qualities are

beyond dispute. He displayed great military insight in critical situations and

this meant using whatever tactics worked.

The instances of surprise attacks, night marches and

ambushes gathered in this chapter show how common ambushes had become in Greek

warfare. This included not only light-armed troops but also hoplites being used

for manoeuvres off the regular battlefield. Against hoplites, the function of

peltasts was so often harassment, and the night was the most advantageous time.

Isocrates equated peltasts with pirates.

Pursuing a fleeing army was a tactic that also became more

common because of the mobility of light-armed troops. Plutarch tells us that

the Spartans thought it ignoble for the Greeks to kill men who were fleeing,

and adds that this policy made enemies more inclined to run away than fight.

The practical reason for doing this, however, was not a lack of morality but

rather a tactic to avoid the kind of thing that happened after the Battle of

Haliartus in 395. The Thebans pursued the Spartans into the hills, where the

Spartans immediately turned on them and attacked back with javelins and stones.

They killed more than 200 Thebans. Practicality played a bigger part in Greek

military policy than moralising.

The shock over the effectiveness of these new soldiers and

their new tactics became apparent when a detachment of peltasts won a brilliant

victory over Spartan soldiers at Lechaeum in 394. The commanders Callias and

Iphicrates, looking down from the walls of Corinth, could see an approaching

mora of Spartan soldiers. The Spartans were not numerous and were not

accompanied by any light-armed or cavalry. The Athenans commanders determined

that it would be safe to stage an ambush with their own peltasts. They could

aim their javelins at the Spartans’ unshielded side when they passed. Callias

stationed his hoplites in the ambush not far from the city walls, while

Iphicrates led the peltasts in an attack, knowing if they lost they could

retreat more quickly. The Spartan commander ordered a group of the youngest

soldiers to pursue the assailants, but when they did so they caught no one,

since they were hoplites pursuing peltasts at a distance of a javelin’s cast.

Besides, Iphicrates had given orders to the peltasts to retire before the

hoplites got near them. Then, when the Spartans were returning from their

pursuit, out of formation because each man had pursued as swiftly as he could,

Iphicrates’ troops turned around and not only did those in front again hurl

javelins at the Spartans but others on the flank also ran and attacked them on

their unprotected side.

Having lost many of their best men, with their returning

cavalry’s support, the Spartans again attempted to pursue the peltasts. Yet

when the peltasts gave way, the cavalry bungled the attack by not pursuing the

enemy at full speed but, rather, kept an even pace with the hoplites in both

their attack and their retreat. Finally, not knowing what to do, the Spartans

gathered together on a small hill about two stades distant from the sea and

about sixteen or seventeen stades from Lechaeum. When the Spartans in Lechaeum

realised what was happening, they got into boats and sailed alongside the shore

until they were opposite the hill. The men on the hill were now at a loss as to

what to do; they were suffering dreadfully, and dying, while unable to harm the

enemy in any way, and in addition they now saw the Athenian hoplites coming at

them. At this point they gave way and fled, some throwing themselves into the

sea, while a few made it to safety to Lechaeum with the cavalry. The total dead

from all the skirmishes and the flight was enormous; the Spartans had lost half

their number in a skirmish with Iphicrates’ peltasts.

Iphicrates, the ambusher, had to beware of ambushes himself.

Polyaenus reports that the Spartan harmost (military governor) set an ambush

that caught Iphicrates off-guard while he was marching towards the city of

Sicyon in 391. Iphicrates immediately retreated by a different, short,

trackless route. He selected his strongest troops, fell on the ambushers

suddenly and killed them all. He admitted that he made a mistake by not

reconnoitring the area, but he exploited his prompt suspicion of an ambush well

by quickly attacking the ambushers.

Iphicrates won several successes in the Corinthian war, such

as the recapture of Sidous, Krommyon and Oinoe from the Spartans. Several

scholars have seen the similarities in the tactics used by Iphicrates’ peltasts

and those that the Aetolians had used against Demosthenes, or that Demosthenes

in turn used against the Spartans on Sphacteria. The success of Iphicrates was

a suggestive sign of the future which might be in store for the professional

peltast. The fact that they could defeat the Spartans boosted their ego and was

a blow against Spartan prestige. As Parke describes it:

This success of the peltasts … was sufficient to make

Iphicrates’ name forever as a general. Moreover it conferred on this type of

light-armed troops a reputation for deadliness in battle which they had never

before enjoyed in popular estimation. To this new esteem may be attributed the

frequent appearance of peltasts in all armies, especially in the Athenian,

during the next half-century. Henceforth, they become the typical form of

light-armed troops and superseded the less-clearly specified, earlier

varieties.

Ambushing, at what some commentators consider ‘inappropriate

times’, now became a habit. Of course, what other time than ‘inappropriate’

could an ambush be? Several surprise attacks are attributed to Iphicrates by

Frontinus. In one, Iphicrates attacked a Spartan camp at an hour when both

armies were accustomed to forage for food and wood.

Another ambush on which Xenophon provides fairly detailed

information took place in 388 in the Hellespontine region. The Spartans sent

Anaxibius to Abydos as harmost (military governor) to relieve Dercylidas. He

immediately took the offensive against the Athenians and their allies. The

Athenians feared Anaxibius would find a way to weaken their position, and sent

Iphicrates with eight ships and 1,200 peltasts to the Hellespont. First the two

commanders just sent raiding parties against each other, using irregulars. Then

Iphicrates crossed over by night to the most deserted portion of the territory

of Abydos, and set an ambush in the mountains. He ordered his fleet to sail

northwards along the Chersonese in order to deceive Anaxibius into believing

they had left the area. Anaxibius suspected nothing and marched back to Abydos,

but made his march in a rather careless fashion. Iphicrates’ men in the ambush

waited until the vanguard of hoplites from Abydos had reached the plain, and at

the moment when the rearguard consisting of Anaxibius’ Spartans started coming

down from the mountains they sprang the ambush and rushed to attack the

rearguard. Anaxibius’ army formed a very long and narrow column and it was

practically impossible for his other troops to hasten uphill to the aid of the

rearguard. He stayed where he was and fought to the death with twelve other

Spartans. The rest of the Spartans fell in flight. Only 150 hoplites from the

vanguard still managed to get away but only because they had been in the front

of the column and were nearer to Abydos. This makes the probable percentage of

losses in the middle of the column somewhere between that of the totally

destroyed rearguard and the twenty-five per cent of the vanguard. Iphicrates

went back to the Chersonese with a successful operation behind him. This

carefully planned ambush, and indeed Iphicrates’ victory, have been compared to

a successful guerrilla operation. With the defeat and death of Anaxibius, the

danger for Athens of Sparta getting supremacy in the Hellespont was over.

Iphicrates continued to operate against the Spartans in these parts until the

Peace of Antalcidas, after which he entered the service of the Thracian kings.

When Iphicrates left for the Hellespont in 388, Chabrias succeeded him as

commander of the peltasts in Corinth. Because he had served under Thrasyboulus

in the Hellespontine region, he was probably trained in the use of peltasts.