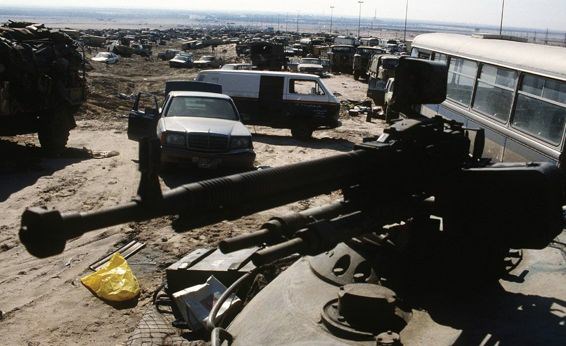

Abandoned cars and trucks clog the Basra–Kuwait highway out of Kuwait City after the retreat of Iraqi forces during Operation Desert Storm. In the foreground is an Iraqi DShKM 12.7 mm anti-aircraft gun mounted on a tank turret.

The Highway of Death

Once the ground war commenced, Iraqi troops quickly decided

to abandon Kuwait and retreat behind the Republican Guard screen. The US

Marines’ feints had convinced them that they also faced an amphibious assault

from the Gulf that would turn their flank. The Iraqis’ flight from Kuwait City

began on the night of 25 February 1991, and the roads north to Basra soon

became choked with massive numbers of fleeing vehicles. The next day about a

thousand Iraqi vehicles on Highway 80 were destroyed by air strikes after the

Muttla Pass was blocked.

The SAAF and Kuwaiti forces were almost in Kuwait City by 26

February, heralding the beginning of the end for the remains of the Iraqi Army

in the KTO. The US Marines were on the outskirts, whilst XVIII Corps was in the

Euphrates Valley and VII Corps was making progress against the Republican

Guard. Nonetheless, units of an Iraqi armoured division decided to stand and

fight in Kuwait City, perhaps with the express intention of buying time for

their retreating comrades.

Liberation of the city followed a large-scale tank battle at

the international airport. During the fighting the Iraqi 3rd Armoured Division

(a veteran not only of the Iran–Iraq War but also the 1973 Arab–Israeli Yom

Kippur War) lost over a hundred tanks. The US 1st Marine Division destroyed 310

Iraqi tanks in total across Kuwait. Iraqi defences had now all but collapsed,

as it became every man for himself. The coalition victory was soon tainted by

allegations that the fleeing Iraqis were needlessly massacred. Despite the

media’s lurid claims of a ‘turkey shoot’, most of the vehicles on Highway 80 –

the ‘highway of death’ – were abandoned. Brigadier Patrick Cordingley recalled,

‘There were not thousands of bodies, as the media claimed, but certainly

hundreds; it was a reminder to all of us of the horror of war.’

Photographs of Highway 80 and the Muttla Pass showed that

the bulk of the vehicles caught on the road were in fact stolen civilian cars,

minibuses, pick-up trucks and tanker lorries; there was even a fire engine. The

few military vehicles on the highway included several Brazilian Engesa EE-9

Cascavel armoured cars (Iraq had obtained 250 Cascavels during the 1980s, but

it is not known how many were committed to the fighting in 1990–91), some army

lorries and fuel trucks, and a tank transporter carrying an unidentified

armoured vehicle. The most vivid and publicly damaging image was Kenneth

Jarecke’s photo of the completely charred head and shoulders of an Iraqi

soldier leaning through the windscreen of his burnt-out vehicle. In the

public’s mind it had been a shameful massacre, rather than a defeated army

receiving its just desserts.

Although the media had a field day with the horrific images

from Highway 80, very few photos emerged of knocked-out Iraqi armour, and most

of those examples that were depicted were old Iraqi T-55s. For example, at the

end of February 1991 a T-55 was found on fire after being hit by a US 82nd

Airborne Division anti-tank missile. Likewise, in early March an entrenched

T-55 was shown burning behind its sand berm as a coalition lorry sped past.

British Centurion AVREs (Armoured Vehicle Royal Engineers)

of the 1st Armoured Division were sent to help clear the charred debris from

the Kuwait–Basra road, and two were photographed brushing aside a lorry and a

car. About two dozen of these fifty-year-old veterans were used to deal with

Saddam’s anti-tank berms as Britain had nothing newer. Two were destroyed in a

fire and one has since found its way into the safekeeping of the UK’s Cobbaton

Combat Collection (coincidentally the collection also has a GS 1 tonne 4×4

Rover, which is believed to have seen service with an artillery unit during

Desert Storm, and a Ferret Mk2/3 4×4 scout car in Gulf War markings).

In truth, there was no ‘Mother of Battles’, as Saddam had

threatened. Coalition forces only fought about 35 per cent of those Iraqi

troops assessed to be in-theatre. The front echelon conscripts of Saddam’s army

were evidently expendable, whilst his loyal Republican Guard units largely

managed to slink away with their bruised tails between their legs, to wreak

more havoc in the months following the cease-fire.

What happened to Iraq’s half a million troops in the KTO?

Having spent six weeks pinned down by Desert Storm’s relentless air attacks,

Iraqi morale was at rock bottom and desertion rife. The western media played

its part. Images of the ‘Basra Pocket’, Highway 80 and the Muttla Pass were

seared into the western psyche, giving the impression that the battle for

Kuwait City had all but crushed the Iraqi Army, making an honourable cease-fire

an imperative. But were Saddam’s regular army and Republican Guard really as

soundly defeated as the West believed, or had the Coalition been chasing

shell-shocked stragglers whilst the bulk of the Iraqi forces fled north in

terror?

Rather than the 540,000 men initially assessed to be in the

KTO, it is now believed they actually numbered about 250,000 (about 150,000 of

them inside Kuwait). It has been estimated that there were probably only

100,000–200,000 men in theatre when the ground war started. These discrepancies

in the figures were due to Saddam deploying a large number of under-strength

divisions to give the impression that his forces were stronger than they really

were. Washington claimed there were forty-three Iraqi divisions in the KTO,

though western media sources only ever identified thirty-five.

Casualties for the Coalition were remarkably light. For

example, America lost 148 killed in action and some 340 wounded; in addition,

there were also almost 100 non-combat fatalities. The British lost thirty-six

dead (seventeen of them in combat), and forty-three wounded. Friendly fire was

a major contributor to the combat losses, with as many as thirty-five US

personnel killed and seventy-two wounded by their own side. Likewise, nine

British personnel were killed and thirteen wounded in unfortunate friendly fire

incidents.

The Basra Pocket

While the Coalition fought to free Kuwait City, up to 800

American tanks from the US VII Corps’ 1st and 3rd Armored Divisions and the 2nd

Armoured Cavalry Regiment launched attacks on a Republican Guard division

inside Iraq, which lost 200 tanks. They then moved forwards and engaged a

second division. American Apache attack helicopters and A-10 Thunderbolt

tank-busters also played a significant role. One Apache alone destroyed eight

T-72s, and on 25 February two USAF A-10s destroyed twenty-three Iraqi tanks,

including some T-72s, in three close air support missions.

In the envelopment the US M1A1 tanks easily outgunned the

Iraqi T-72s, and in a night engagement on 25/26 February the Guards’ Tawakalna

Armoured Division was largely destroyed without the loss of a single US tank.

The Republican Guard, unable to stem the American armoured tide, tried to

retreat, and the next morning a brigade of the Medina Division, supported by a

battalion from the 14th Mechanized Division, attempted to protect the

withdrawal. The Medina troops found themselves under attack from the US 1st and

3rd Armored Divisions, while the remnants of the Tawakalna were finished off by

air attacks.

Caught as they were being loaded onto their tank

transporters, the Medina Division’s armoured vehicles were bombed by USAF A-10s

and F-16 fighters. Apache attack helicopters caught another eighty T-72 tanks

still on their transporters along Route 8. Although not all the roads out of

Basra were closed, the Coalition was determined that Iraqi tanks and artillery

should not escape. The US VII Corps’ armour also fought the Hammurabi

Republican Guard Division 80km to the west of Basra.

The US 24th Mechanized Division, having made a dramatic

150-mile drive northwards to join the US 101st Airborne Division on the

Euphrates, now swung to the right to block the Iraqi escape route. The six

remaining Republican Guard divisions had been trapped overnight in a swiftly

diminishing area of northern Kuwait and southern Iraq, with their northward

line of escape largely severed.

On 27 February the US 24th Mechanized Division attacked the

Guard’s Hammurabi Armoured Division, the al-Faw and Adnan Infantry Divisions

and the remnants of the Nebuchadnezzar Infantry Division. They fled, with the

Nebuchadnezzar Division possibly escaping over the Hawr al-Hammar Lake

causeway. The 24th Mechanized Division also captured fifty Republican Guard

T-72 tanks as they were fleeing north along a main road near the Euphrates. It

was all but over for the Guards.

Six disparate brigades with fewer than 30,000 troops and a

few tanks were now struggling back to Basra. The Iraqis agreed to a cease-fire

the following day, whilst the British 7th Armoured Brigade moved to cut the

road to Basra just north of Kuwait City. However, some troops continued to

escape across the Hawr al-Hammar and north from Basra along the Shatt al-Arab

Waterway. Brigadier Cordingley, Commander of the 7th Armoured Brigade, noted,

‘By 28 February it was clear that General Schwarzkopf’s plan to annihilate the

Republican Guard with a left hook through Iraq had failed … The majority of the

Iraqi soldiers were already on their way back to Baghdad.’

Firmly in control of Iraq’s state media, Saddam had no need

to acknowledge this terrible defeat, and instead victory was given as the

reason for abiding by the ceasefire. Baghdad Radio announced, ‘The Mother of

battles was a clear victory for Iraq … We are happy with the cessation of

combat operations as this would preserve our sons’ blood and people’s safety

after God made them triumphant with faith against their evil enemies.’

Only a residual Iraqi threat remained by 30 February. Two

Iraqi tank brigades were south-west of Basra, another brigade with forty

armoured vehicles was to the south and an infantry brigade was on either side

of the Hawr al-Hammar Lake. In total, about eight armoured battalions, the

remnants of those Iraqi forces deployed in and around Kuwait, were now trapped

in the ‘Basra Pocket’. Basra itself lay in ruins, and marshes and wetlands to

the west and east made passage impossible.

Despite the cease-fire, the US 24th Division fought elements

of the Hammurabi Division again on 2 March after reports that a battalion of

T-72 tanks was moving northwards towards it in an effort to escape. The Iraqi

armoured column foolishly opened fire and suffered the consequences. The

Americans retaliated with Apache attack helicopters and two task forces,

destroying 187 armoured vehicles, 34 artillery pieces and 400 trucks. The

survivors were forced back into the ‘Basra Pocket’. By this stage Iraq only had

about 700 of its 4,500 tanks and 1,000 of its 2,800 APCs left in the KTO and,

with organized resistance over, the Iraqis signed the cease-fire on 3 March

1991.

In the wake of Desert Sabre, only the Iraqi Army Air Corps

and the Republican Guard Corps secured favour with Saddam Hussein, by swiftly

crushing the revolt in the south against his regime and containing the

resurgent Kurds in the north. In contrast the Iraqi Army and Iraqi Air Force

had fled Desert Storm and remained under a cloud. Subsequently the IrAF found

itself grounded by the Coalition’s ceasefire terms, while the army was left

face to face with the barrels of the Republican Guard Corps’ remaining tanks.

After a brief stand-off, the Iraqi Army opted for the status quo, but its

loyalty and competence remained tarnished by its collapse and by the actions of

thousands of deserters.

In 1991 the Coalition accounted for just six Iraqi

helicopters (one Mi-8, one BO-105 and four unidentified) in the air and another

five on the ground. General Schwarzkopf had cause to regret that they did not

destroy more. During the ceasefire talks on 3 March 1991 the Iraqis requested

that, in light of the damage done to their infrastructure, they be allowed to

move government officials around by helicopter. Without fully realizing the

consequences, Schwarzkopf agreed not to shoot down ‘any’ helicopters flying

over Iraqi territory. Thus, by using his helicopter gunships Saddam was able to

crush the rebellion in Iraq’s cities and the southern marshes and Kurdish

advances in the north with impunity, despite his defeat in Kuwait.

In hindsight, Schwarzkopf felt that grounding Iraqi

helicopters would have made little difference. In his view the Iraqi armour and

artillery of the twenty-four remaining divisions, which had never entered the

war zone, had a far more devastating impact on the rebels. This was a little

disingenuous, for while tanks and artillery were instrumental in crushing the

revolts in the predominantly Shia cities of Basra, Karbala and Najaf (the scene

of Shi’ite unrest in 1977, resulting in 2,000 Shia arrests and another 200,000

being expelled to Iran), in the southern marshes the Republican Guard’s T-72

tanks could not operate off the causeways and artillery was only effective

against pre-spotted targets. In fact the Iraqi Army Air Corps played a pivotal

role over Iraq’s rebellious cities, the southern marches and the Kurdish

mountains.

Over the cities helicopter gunships were used

indiscriminately to machine gun and rocket the civilian population in order to

break their morale. Although there was no evidence of the use of chemical

weapons (Saddam did not want to provoke further coalition intervention so

stayed his hand), on at least one occasion residential areas were reportedly

sprayed with sulphuric acid. This was corroborated by French military units

still in southern Iraq, who treated Iraqi refugees with severe acid burns.

Although the rebellion was mainly a spontaneous outburst by

defeated and disaffected troops returning home, its religious Shia basis meant

that it was ultimately doomed. America stood by, as a Shia victory would only

serve radical Shia Iran, and as a result the rebels did not even receive

airdrops of manportable anti-aircraft and anti-tank missiles with which to fend

off Saddam’s helicopters and tanks. The Iraqi military, dominated by the Sunni

minority, went about their business unhindered.

After authority had been brutally reasserted in the cities,

thousands fled into Iraq’s southern marshes seeking sanctuary. Here the IAAC

was even more instrumental in the destruction of those forlorn forces that the

West had vaguely hoped would unseat Saddam. IAAC pilots knew what lay in store

for them if they failed, as General Ali Hassan al-Majid, who was commanding the

operation, warned at least pilot not to return unless he had wiped out some

insurgents obstructing a bridge.

The whole operation in the marshes was largely a repeat of

March 1984, when Iraqi helicopter gunships mercilessly hunted Iranian troops

round the two important Majnoon Island oil facilities. This time they refrained

from using mustard gas or any other chemical agents, but once again the

unburied dead were left to become carrion for the jackals, and those foolish

enough to surrender were shot at point-blank range. The IAAC contributed to the

deaths of an estimated 30,000 rebels. Additionally 3,000 Shia clerics were

driven from Najaf and fled to the Iranian town of Qom.

In the north the fear of another Halabja was sufficient to

scatter the Kurdish population at the first sight of an aircraft. The IrAF and

IAAC once more refrained from deploying chemical weapons, but callously

contented themselves with dropping flour on the refugees, who instantly

panicked. Once more the Iraqi military made use of their helicopters and artillery

to eject the lightly armed Kurdish guerrillas from their recent conquests.

Whilst the IAAC had continued to fly after 1991, in defiance

of the cease-fire terms the IrAF resumed operational and training flights with

its fixed-wing aircraft in April 1992. The IrAF claimed it was responding to

the provocation of an Iranian Air Force attack on an Iranian opposition force’s

base east of Baghdad. In response to these violations, and the repressive

military operations, the UN imposed two separate no-fly zones in the north and

south of the country.

Due to UN sanctions and financial restrictions, the Iraqi

Air Force could only manage about a hundred sorties per day, down from 800 in

the heyday of the Iran–Iraq War. Residual IrAF capabilities remained in the

Baghdad, Mosul and Kirkuk areas, protecting Saddam from dissidents and the

Kurds. Throughout most of the 1990s the IrAF spent much of its time dodging the

northern and southern no-fly zones, though at least two fighters (a MiG-23 and

a MiG-25) were lost for violating these zones.