PEGASUS BRIDGE

The Orne River bridges were strategic targets on the night

of 5–6 June. Spanning the river and canals at the east end of the landing

beaches, they were attacked by elements of the British Sixth Airborne Division

to delay German counterattacks against Sword Beach.

The structure that became known as Pegasus Bridge was at Benouville, nearly three miles south of Ouistreham on the coast. It was a small span, which, with the nearby Ranville Bridge, was seized in a textbook assault by six Horsa gliders under Maj. John Howard. As a result of the British attack, the Café Gondrée, owned by the family of that name, became the first French building liberated in the Normandy campaign. Today the cafe houses a small museum in tribute to the Sixth Airborne troopers who led the assault. Because of its age, the Pegasus Bridge was replaced with a replica after the war. The original bridge rests beside the cafe as part of the museum displays.

AIRCRAFT

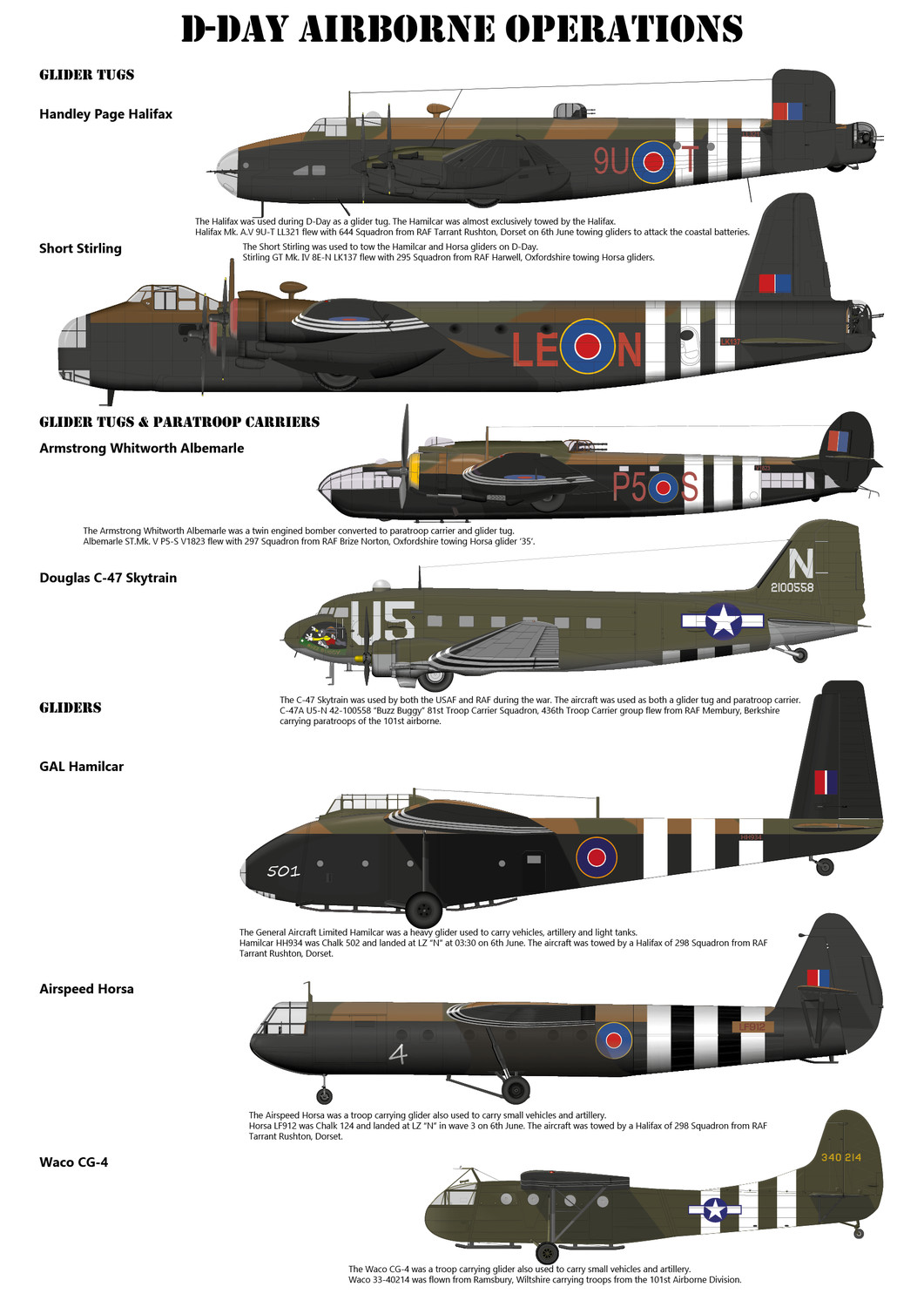

Handley-Page Halifax

The four-engine, twin-tail Halifax bore a general

resemblance to its more famous counterpart, the Avro Lancaster, and shared the

“Lanc’s” rags-to-riches story. The Lancaster evolved from the Avro Manchester;

similarly, the Halifax began life on the drawing board as a twin-engine bomber

but was altered to the multi-engine configuration. Originally powered by four

1,280 hp Rolls-Royce Merlins, the Halifax Mark I first flew in October 1939,

barely a month after the war began. However, developmental problems delayed its

combat debut until March 1941. The original version, as well as the Mark II and

V, retained Merlins until increased demand for Lancasters, Spitfires, and

Mosquitos mandated an engine change.

The most common Halifax variants were the Mark III, VI, and

VII, all powered by Bristol Hercules air-cooled radials of 1,600 to 1,800

horsepower. The later models also had a different silhouette, with the original

front turret deleted in favor of a more streamlined nose to improve top speed.

The Mark III was rated at 277 mph.

Halifaxes dominated RAF Bomber Command’s No. 4 and 6 Groups

but also flew in Coastal Command and Transport Command. Like most British

bombers, the Halifax was a single-pilot aircraft, with six other men completing

the crew: flight engineer, bombardier (bomb aimer in the RAF), navigator, and

gunners. In four years of RAF Bomber Command operations, Halifaxes logged

75,500 sorties with an average bomb load of three thousand pounds.

Extremely versatile, the Handley-Page bomber doubled as a

maritime patrol plane, electronic countermeasures platform, paratroop

transport, and glider tug. The latter duty was an especially important aspect

of the Halifax’s contribution to Overlord. In June 1944 at least twenty Halifax

squadrons flew from the UK with Bomber Command while others served in the

Mediterranean theater.

Total production was 6,176 aircraft, including some postwar

manufacture. The type remained in RAF service until 1952.

Armstrong Whitworth

A.W.41 Albemarle

The first three production Albemarles left the factory in

December 1941, by which time the decision had been made to adapt the aircraft

as a glider tug and airborne forces transport.

Deliveries to the RAF began in January 1943 when No. 295

Squadron received its first aircraft; the type was blooded with Nos. 296 and

297 Squadrons, part of No. 38 Wing operating from North Africa, in the invasion

of Sicily in July 1943. On D-Day (6 June 1944) six No. 295 Squadron Albemarles

operating from Harwell, served as pathfinders for the 6th Airborne Division,

dropping paratroops over Normandy.

In the glider tug role, four squadrons of Albemarles were

used to tow Airspeed Horsas to France in support of ground operations, while in

September 1944 two of No. 38 Group’s squadrons participated in the ill-fated Arnhem

operation, towing gliders carrying troops of the 1st Airborne Division.

Production of the Albemarle, apart from the prototypes, was undertaken by A. W.

Hawksley Ltd, part of the Hawker Siddeley Group: production came to an end in

December 1944 when 600 Albemarles had been built. Original orders had covered 1,080.

Douglas C-47 Skytrain

Arguably the most important aircraft in history, the Douglas

DC-3 airliner revolutionized the commercial aviation industry when it appeared

in 1935. By 1940 its military potential was obvious, and the Army Air Corps

issued a contract to Douglas that year. With a simplified interior,

strengthened fuselage, and wide cargo doors, the Skytrain could carry

twenty-seven troops, up to twenty-four casualty litters, or five tons of cargo.

Two reliable Pratt and Whitney radial engines of 1,200 horsepower each gave the

C-47 the altitude performance to cross some of the world’s highest mountain

ranges.

Total USAAF acceptances of transports based on the DC-3 was

10,343 during the war years, with nearly half delivered in 1944. During that

year a typical Skytrain cost $88,578. The army total included some four hundred

civilian airliners impressed into service with various numerical designations

(C-48 to C-84); some of the subvariants were named “Skytroopers.” RAF use of

the type was extensive, under the name “Dakota.” C-47s are well depicted in the

movie Band of Brothers.

After the war, Gen. Dwight Eisenhower listed the C-47 as one

of the major reasons for victory in Europe. Certainly its contribution to

Overlord was significant, as more than nine hundred Skytroopers and Skytrains

provided most of the airlift for American and British paratroopers, in addition

to towing gliders. Seventeen C-47s were shot down on 5–6 June.

The “Gooney Bird” was so adaptable that the U.S. Air Force

still retained a thousand C-47s in 1961. Some of those were converted to

“gunships” with heavy machine-gun and cannon armament during the Vietnam War.

GLIDERS

General Aircraft

Hamilcar

Recognizing the need for armored support of airborne forces,

the British Air Ministry requested a large glider that could deliver a

seven-ton light tank or forty troops. Named for the Carthaginian general, the

Hamilcar entered service in 1942 and usually carried a Tetrach tank. With a

110-foot wingspan and thirty-six-thousand-pound gross weight, it was the

largest and heaviest glider built by any of the Allied powers. Of some four

hundred Hamilcars produced, seventy were employed in Normandy. Others were

flown in the Arnhem operation three months later.

Airspeed Horsa

Britain’s primary combat glider, the Airspeed Horsa, shared

the American CG-4’s general configuration and service history. Like the U.S.

Waco, the Horsa was first flown in 1941. Also like the CG-4, it had a hinged

nose to facilitate loading troops and small vehicles. With a two-man crew and

capacity of twenty-five troops, it was capable of heavier loads than the Waco,

partly due to its larger size (8,370 pounds empty and eighty-eight-foot

wingspan). Tow speeds are listed between 100 and 150 mph.

Horsas were committed to combat in the invasion of Sicily in

July 1943 and, like the Waco, figured prominently at Normandy and Operation

Market-Garden, the Holland operation of September 1944. Some 355 gliders were

involved in the British airborne phase of Overlord, with a hundred pilots

killed or injured.

Total Horsa production was 3,655 aircraft.

Waco CG-4

With five airborne divisions, the U.S. Army needed large

quantities of gliders in addition to transport aircraft for paratroopers. The

need was met by Waco Aircraft Company’s CG-4 (Cargo Glider Model 4), which was

accepted in 1941. The CG-4A was a large aircraft, with a wingspan of

eighty-three feet eight inches, and a hinged nose to permit the cockpit portion

to be raised for easy vehicle loading. Standard loads were thirteen troops, a

jeep with crew, or a 75 mm pack howitzer and crew.

The Waco could be towed at 125 mph, usually by a Douglas

C-47. When within range of its objective, the glider’s tow line was released

and the two-man crew made the approach to the landing zone. Its steel tube

fuselage proved stronger than those of most British gliders, which were made of

wood.

CG-4s were introduced to combat in the Sicilian invasion of July 1943 and were also widely employed in Overlord and in Anvil-Dragoon, the invasion of southern France in August 1944. In far smaller numbers they also saw action against Japan. Some twelve thousand were built throughout the war, with 750 provided to Britain’s Glider Pilot Regiment. In keeping with RAF practice of “H” names for gliders, the Waco was dubbed the “Hadrian.”

AIRBORNE OPERATIONS

In the fifteenth century Leonardo Da Vinci envisioned

airborne soldiers, and in the nineteenth century Napoleon Bonaparte pondered

invading Britain with French troops in hot-air balloons. But not until the

1940s did the technology exist to transport large numbers of specially trained

soldiers behind enemy lines and deliver them by parachute, glider, or transport

aircraft.

German airborne forces included paratroops and glider and

transport-lifted infantry, all controlled by the Luftwaffe. Eventually nine parachute

divisions were established, but few Fallschirmjaeger (literally “parachute

hunters”) made combat jumps. Nonetheless, Germany led the way in combat

airborne operations, seizing Belgium’s Fort Eben Emael in 1940. The Luftwaffe

also made history in the first aerial occupation of an island—the costly Crete

operation in 1941. However, Germany’s Pyrrhic victory proved so costly that no

Fallschirmjaeger division was again involved in a major airborne operation.

Thereafter, the Luftwaffe parachute forces were employed as light infantry in

every theater of operation. Two German airborne divisions, the Third and Fifth,

responded to the Allied invasion in Normandy but were hampered by inadequate

ground transport.

The British army authorized small airborne units in 1940 but

did not form the Parachute Regiment until 1942. That unit served as a training

organization, producing seventeen battalions, of which fourteen were committed

to combat. The battalions were formed into the First and Sixth Airborne

Divisions, the latter involved in Operation Overlord. Both divisions were

committed to the Arnhem assault, Operation Market-Garden, in September 1944.

The U.S. Army formed five airborne divisions during World

War II, of which three (the Eighty-second, 101st, [see U.S. Army Units] and

Seventeenth) saw combat in the Mediterranean or the European Theater of

Operations. The Eleventh served in the Pacific; the Thirteenth went to Europe

in 1945 but was not committed to combat.

Apart from isolated uses of airborne battalions, the first

Allied airborne operation of note occurred during Operation Husky, the

Anglo-American invasion of Sicily in July 1943. Subsequent operations on the

Italian mainland perfected doctrine and techniques so that by 1944 the United

States and Britain could integrate three airborne divisions into the plan for

Overlord. By isolating the vulnerable beachheads from German reinforcements

during the critical early hours of 6 June, the airborne troopers gained

valuable time for the amphibious forces.

Later uses of British and American airborne forces included

the Arnhem operation in September 1944 and the Rhine crossing in March 1945.

Airborne operations were considered high-risk undertakings,

requiring commitment of large numbers of valuable assets—elite troops and

airlift—and incurring the danger of assault troops being isolated and

overwhelmed. The latter occurred on a large scale only once, when supporting

Allied ground forces were unable to reach British paratroopers at Arnhem,

Holland, in September 1944.

Because they were by definition light infantry—without

armored vehicles or heavy artillery—paratroopers were laden with enormous

personal burdens. Many D-Day troopers carried nearly two hundred pounds of

equipment, including their main and reserve chutes, life preserver, primary and

secondary weapons and ammunition, water and rations, radios or mines, and other

gear. It could take as much as five minutes for a trooper to pull on his

parachute harness over his other equipment, and if they sat on the ground many

men needed help standing up.

Normal parameters for dropping paratroopers were six hundred

feet of altitude at ninety miles per hour airspeed. Owing to weather and

tactical conditions, however, many troopers were dropped from 300 to 2,100 feet

and at speeds as high as 150 miles per hour.

American paratroopers had to make five qualifying jumps to

earn their wings, after which they received a hazardous-duty bonus of fifty

dollars per month, “jump pay.”

The U.S. Eighty-second and 101st Airborne Divisions dropped

13,400 men behind Utah Beach on the west end of the Allied landing areas, while

nearly seven thousand men of the British Sixth Division secured bridges behind

Sword Beach to the east. The primary objective of the airborne troops was to

isolate the beachhead flanks from substantial German reinforcement; the British

were more successful than the Americans in doing so. The Sixth Division’s

seizure of the Orne River bridges became a classic airborne operation.

The elite of the elite among paratroopers were the

pathfinders, who were first on the ground. Preceding the main force by nearly

an hour, the pathfinders were responsible for guiding troop-carrier aircraft to

the landing zones and for marking the target areas. Specialized navigational

equipment included the Eureka/Rebecca radar beacon, which transmitted to the

lead aircraft in each C-47 formation, and automatic direction-finder (ADF)

radios. Holophane lights were laid in T patterns on the ground to mark each

drop zone.

Owing to fog, enemy action, and the confusion common to

warfare, in Overlord only one of the eighteen U.S. pathfinder teams arrived at

the correct drop zone. One entire eight-man team was dropped into the English

Channel.

Because of wide dispersion over the Cotentin Peninsula, only

about one-third of the American paratroopers assembled themselves under

organized leadership, and many landed in the wrong divisional areas. One

battalion commander roamed alone for five days, killing six Germans without

finding another American. While some troopers sought cover or got drunk on

Calvados wine, many others displayed the initiative expected of elite troops.

In Normandy the airborne was especially effective in disrupting German

communications.

Glider-borne infantry regiments were part of every airborne

division, and though they did not originally receive “jump pay,” these soldiers

were still part of an elite organization. Gliders possessed the dual advantages

of delivering a more concentrated force to the landing zone and providing

certain heavy equipment unavailable to paratroopers—especially light artillery

and reconnaissance vehicles. Gliders were usually flown by noncommissioned

pilots, who, once on the ground, took up personal weapons and fought as part of

the infantry units they had delivered to the target.

82nd Airborne

Division

Activated by Maj. Gen. Omar N. Bradley at Camp Claiborne,

Louisiana, on 25 March 1942, the Eighty-second Division was designated an

airborne formation on 15 August and began jump training at Fort Bragg, North

Carolina, in October. By then the commanding general was Matthew B. Ridgway,

who would remain at the helm for two years. Deployed to North Africa in May

1943, the “All Americans” jumped into Sicily on 9 July and shuttled around the

Mediterranean theater until moving to Northern Ireland in time for Christmas.

D-Day training was conducted in England from February 1944, leading up to Drop

Zone Normandy.

Through most of its combat career the division included the

504th and 505th, 507th, and 508th Parachute Infantry Regiments (the latter two

detached from the Seventeenth Airborne Division), plus two glider and two

parachute field artillery battalions. Dropped behind Utah Beach on the eve of

D-Day (minus the 504th, still understrength from Italy), the Eighty-second was

spread between Sainte-Mère-Église and Carentan. The next day the paratroopers

were reinforced by the 325th Glider Infantry Regiment, arriving by air and

overland via the newly won beachhead.

•505th PIR: Lt. Col. William E. Ekman.

•507th PIR: Col. George V. Millett, Jr.

•508th PIR: Col. Roy E. Lindquist.

•325th GIR: Col. Harry L. Lewis.

Of 6,400 All Americans who jumped into Normandy, nearly 5

percent were killed or injured in the drop. The 507th’s commander, Colonel

Millett, was captured on D+2 and was succeeded by Lt. Col. Arthur Maloney. In

the three weeks after D-Day the division lost 457 killed, 2,571 missing, twelve

captured, and 1,440 wounded. However, many of the missing subsequently rejoined

their units, having been dropped far from their assigned zones.

Despite persistent German opposition along the Merderet

River, the division established a bridgehead at La Fiere on D+3. The next day,

10 June, the 505th seized Montebourg Station, and on the 12th the 508th crossed

the Douve River, reaching Baupt on the next day. On D+10 the 325th and 505th were

as far as St. Sauveur-le-Vicomte, and the division occupied another important

bridgehead, at Pont l’Abbé, on the 19th. Ridgway’s troops then attacked along

the west coast of the Cotentin Peninsula, and on 3–4 July took two important

hills overlooking La Haye-du-Puits. Following five weeks of almost nonstop

combat, the Eighty-second was withdrawn to England.

In August, Ridgway was succeeded by Maj. Gen. James M.

Gavin, who prepared the division for its next operation. That jump occurred

during Operation Market-Garden at Nijmegen-Arnhem, Holland, in September,

followed by operations in Belgium and Germany. On VE-Day in May 1945 the

division was engaged along the Elbe River. In all, the Eighty-second sustained

8,450 casualties (1,950 dead) throughout the war.

101st Airborne

Division

The “Screaming Eagles” were activated at Camp Claiborne,

Louisiana, on 15 August 1942 under Maj. Gen. William C. Lee, who turned over to

Maxwell D. Taylor in March 1944. Arriving in England in September 1943, the

101st began intensive training for Normandy with the 327th and 401st Glider

Infantry plus the 501st, 502d, and 506th Parachute Infantry Regiments.

•501st PIR: Col. Howard R. Johnson

•502d PIR: Col. George V. H. Moseley, Jr.

•506th PIR: Col. Robert F. Sink

•327th GIR: Col. George S. Wear

On the night of 5–6 June, Taylor’s division air-assaulted

into Normandy, securing beach exits from St. Martin to Pouppeville. On D+1 the

506th pushed southward from Cauloville and encountered stiff resistance near

St. Come-sur-Mont. The next day, the 8th, the division engaged in the battle

for Carentan, with the 502d fighting steadily along the causeway over the next

two days. On the 11th the 502d Parachute and 327th Glider Infantry (reinforced

with elements of the 401st) pushed the Germans into the outskirts of Carentan,

permitting the 506th to occupy the city on the 12th, D+6. The inevitable German

counterattacks were repelled over the next two weeks, at which time the

Screaming Eagles were relieved by the Eighty-third Infantry Division. In

Normandy the division sustained 4,480 casualties, including 546 known dead,

1,907 missing (many of whom later turned up), and 2,217 wounded.

In late June the 101st moved to Cherbourg and in mid-July

returned to England. There it began refitting before Operation Market-Garden,

the Arnhem operation, which took place that September.

Under the acting division commander, Maj. Gen. Anthony C.

McAuliffe, the Eagles held Bastogne, Belgium, during the Battle of the Bulge.

In nearly a year of combat, the 101st lost 11,550 men, including 3,236 dead or

missing.

Sixth Airborne

Division

Commanded by Maj. Gen. Richard Gale. The division included

the Third and Fifth Parachute Brigades and Sixth Airlanding Brigade, each with

three battalions. The Third Parachute Brigade included the First Canadian

Parachute Battalion. The airlanding brigade comprised one battalion each of the

Devonshire, Oxford, and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry, and Royal Ulster

Rifles.

•Glider Pilot Regiment: Brig. George Chatterton.

•Third Parachute Brigade: Brig. James Hill.

•Fifth Parachute Brigade: Brig. Nigel Poett.

•Sixth Airlanding Brigade: Brig. the Hon. Hugh Kindersley.

The division’s first mission was Operation Tonga on 6 June

1944, D-Day, part of the Normandy landings, where it was responsible for

securing the left flank of the Allied invasion during Operation Overlord. The

division remained in Normandy for three months before being withdrawn in

September. The division was entrained day after day later that month, over

nearly a week, preparing to join Operation Market Garden but was eventually

stood down. While still recruiting and reforming in England, it was mobilised

again and sent to Belgium in December 1944, to help counter the surprise German

offensive in the Ardennes, the Battle of the Bulge. Their final airborne

mission followed in March 1945, Operation Varsity, the second Allied airborne

assault over the River Rhine.

After the war the division was identified as the Imperial

Strategic Reserve, and moved to the Middle East. Initially sent to Palestine

for parachute training, the division became involved in an internal security

role. In Palestine, the division went through several changes in formation, and

had been reduced in size to only two parachute brigades by the time it was

disbanded in 1948.

LEWIS HYDE BRERETON, (1890–1967)

Ironically, one of the U.S. Army Air Force’s most versatile

commanders was a graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy. A Pennsylvanian, Brereton

ranked fifty-fifth of 193 in the Annapolis class of 1911 but soon resigned his

navy commission and transferred to the army’s coast artillery. He was drawn to

the fledgling army air service, learned to fly in 1913, and commanded a

squadron in France during World War I. In the process he became one of Brig.

Gen. William “Billy” Mitchell’s advocates, though Brereton was more interested

in tactical than strategic airpower.

In November 1941 Brereton was named commander of the Far

East Air Forces, serving as Gen. Douglas MacArthur’s air commander in the

Philippines. However, the USAAF was understrength in the region, and

MacArthur’s chief of staff hindered rather than enhanced cooperation. Often

unable to communicate directly with MacArthur, Brereton saw much of his command

destroyed on the ground in Japanese attacks on 8 December, despite several

hours’ warning after Pearl Harbor. Brereton continued fighting the Japanese

after the fall of the Philippines, briefly commanding the Tenth Air Force in

India.

Transferred to the Mediterranean area in June 1942, Brereton

headed the USAAF’s Middle East Air Force (USMEAF), working closely with the

British Royal Air Force. He became a firm advocate of joint Anglo-American air

operations as the best means of defeating the Axis Powers through airpower.

That October he assumed command of the U.S. Desert Air Task Force in time for

the El Alamein offensive, concentrating on close air support as practiced by the

RAF. Based on that experience, Brereton had formulated a doctrine when the MEAF

became the U.S. Ninth Air Force and employed his tenets through much of the

North African 1942–43 campaign. He continued leading the Ninth Air Force in the

Sicilian operation and oversaw Operation Tidal Wave, the low-level B-24

Liberator attack on Romanian oil fields in August 1943.

Soon thereafter the Ninth Air Force moved to Great Britain,

receiving new groups and equipment for the forthcoming invasion of northern

France. The Ninth was designated the U.S. tactical air force, working alongside

the strategically oriented Eighth Air Force. Brereton’s interest in

dive-bombing and tactical airpower, dating from World War I, was reflected in

the successful use of Ninth Air Force fighters as dive-bombers during the

Normandy campaign. The P-38s, P-47s, and P-51s were especially successful in

destroying bridges, preventing or delaying German reinforcement of the

beachheads. Additionally, the Ninth Air Force included Troop Carrier Command,

which delivered paratroopers and gliders to their target zones behind the

invasion beaches on D-Day.

Often considered contentious and uncooperative by

contemporaries, Brereton had especially poor relations with Gen. Omar Bradley.

Their mutual dislike has been attributed in part to the bombing errors in

Operation Cobra, the breakout from the Normandy salient. Whatever the facts,

both commanders bore some of the responsibility for hundreds of “friendly fire”

casualties.

Based on his experience with Airborne Operations, Lieutenant

General Brereton established the First Allied Airborne Army in August 1944.

Shortly thereafter, his forces spearheaded Operation Market-Garden, the

ill-fated Allied drive into the Netherlands.

However, a far more successful operation occurred in March

1945, when Brereton’s airborne troopers led the Rhine crossing. On VE-Day he

was one of the most highly decorated American generals, on the staff of the

U.S. First Army. For his service in two world wars he received the

Distinguished Service Cross, Distinguished Service Medal, Silver Star, Legion

of Merit, Distinguished Flying Cross, Bronze Star, and Navy Commendation Medal.

In early 1946 Brereton joined the evaluation board appointed

by the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff to study the atomic bomb tests at Bikini

Atoll in the Pacific Ocean. Subsequently he published his memoir, The Brereton

Diaries.

Brereton retired in Washington, D.C., where he died at age

seventy-seven.

RICHARD GALE, (1896–1982)

Commanding officer of the British Sixth Airborne Division,

Maj. Gen. Richard Gale led the vertical assault on the eastern flank of the

D-Day beaches. Born in London, he was commissioned in the British army in 1915

and finished the First World War as a company commander, holding the Military

Cross. His postwar service was almost entirely in India, between 1919 and 1936.

However, in 1942 he was selected to form the First Parachute Brigade. He became

first commander of the Sixth Division the next year.

In the Overlord briefing “Windy” Gale told his troopers,

“What you get by stealth and guts you must hold with skill and determination.”

He landed by glider early in the morning of 6 June and directed the seizure of

key bridges leading to the British and Canadian beaches. Gale’s next major

operation was the Rhine crossing in March 1945, and by VE-Day he commanded I

Airborne Corps.

Postwar assignments largely involved the Middle East; Gale

commanded British and UN forces in Palestine and Egypt from 1946 to 1949.

Knighted in 1950, he led the British army of the Rhine and NATO’s Northern Army

Group from 1952 to 1957 and was deputy NATO commander from 1958 to 1960.

Gale’s autobiography, Call to Arms, was published in 1968.

He died in his native London on 29 July 1982, four days past his eighty-fourth

birthday.

Major General Matthew Ridgway and Major General James M. Gavin during the Battle of the Bulge, December 19, 1944.

MATTHEW BUNKER RIDGWAY, (1895–1993)

Commander of the Eighty-second Airborne Division in

Normandy. One of America’s most distinguished soldiers, Matthew Ridgway was the

first U.S.

Army officer named supreme commander in both the Atlantic

and Pacific areas. He was born in Monroe, Virginia, and was appointed to the

U.S. Military Academy in 1913. Following graduation in 1917 he began his army

service with postings to China, Nicaragua, and the Philippines.

In 1941 Ridgway was on the staff of the War Plans Division

in Washington, D.C., but in June 1942 he succeeded Omar Bradley as commander of

the Eighty-second Infantry Division, which became the Eighty-second Airborne in

August. Ridgway led the “All Americans” to North Africa in May 1943, preparing

for their first combat at Sicily in July. From September 1943 to March 1944

Ridgway’s troopers were committed to assaults at Salerno and Anzio, Italy.

Ridgway subsequently took the Eighty-second to Britain in preparation for

D-Day, and on 6 June they dropped into Normandy.

Later in the war, as a lieutenant general, Ridgway commanded

the XVIII Airborne Corps. Postwar assignments included the Mediterranean and

Caribbean commands. In 1949 Ridgway was appointed U.S. Army Deputy Chief of

Staff.

The Korean War began in 1950, and the following year

Ridgway, now a four-star general, replaced Gen. Douglas MacArthur as theater

commander. Ridgway was “triple hatted,” simultaneously serving as UN commander

in chief in Korea, commander in chief of U.S. Forces in the Far East, and

Supreme Commander, Allied Powers in Japan. His appointment, coming after the

stunning reverses inflicted on UN forces by the Chinese, posed a major

leadership challenge, but Ridgway proved equal to the task. Wearing his

trademark hand grenades, he made himself visible to combat troops and oversaw

the strategy that stabilized the front.

In 1952 Ridgway was named supreme commander of Allied Forces

in Europe, the senior NATO post. However, his tenure was short-lived, as he was

recalled to Washington to become army chief of staff in 1953.

Ridgway retired to his native Virginia, where he died in

July 1993 at age ninety-eight. He is buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

MAXWELL DAVENPORT TAYLOR, (1901–1987)

Commander of the 101st Airborne Division in Normandy. Born

in Missouri, Taylor graduated from West Point in 1922 and served in the

engineers and artillery units. He graduated from Command and General Staff

School in 1935, enhancing his growing reputation as a scholar. He studied

French, Spanish, and Japanese, and was attached to the U.S. embassy in Peking,

China, in 1937.

Upon completing the Army War College course in 1940 Taylor

was promoted to major and joined the War Plans Division in Washington, D.C.

After commanding an artillery battalion he joined the staff of the army chief

of staff. From there on he rose rapidly—from lieutenant colonel in December

1941 to brigadier general a year later.

Among the U.S. Army’s earliest parachute officers, Taylor

led the Eighty-second Airborne Division’s artillery in Sicily and Italy.

Promoted to major general in May 1944, he assumed command of the 101st in

Britain and led the “Screaming Eagles” into France. After the Normandy campaign

Taylor took the 101st back to Britain for refitting. He commanded the division

for the rest of the war, leading the Eagles in the Holland jump in September

and through the Battle of the Bulge.

After the war Taylor became superintendent of the U.S.

Military Academy and commanded the Eighth Army at the end of the Korean War.

Promoted to full general, he served as army chief of staff from 1955 to 1959

and then retired, partly to show his opposition to America’s growing reliance

on nuclear weapons. However, he was recalled as chairman of the Joint Chiefs of

Staff during the Kennedy and Johnson administrations, 1962–64. Subsequently he

was ambassador to South Vietnam, 1964–65.

Taylor left a reputation as one of the brightest, most

innovative senior officers of his era.

JAMES MAURICE GAVIN, (1907–1990)

“Jumping Jim” Gavin was one of the young paratroop

commanders who set the style for airborne leadership in the U.S. Army. Born in

New York, he was adopted by a Pennsylvania couple and enlisted in the army at

age seventeen. His potential was recognized early on, and he received an

appointment to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point.

Gavin rose quickly in the airborne forces, assuming command

of the 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment in July 1942. Subsequently he saw

combat with the Eighty-second Airborne Division in Sicily and Italy. As

assistant division commander he jumped into Normandy, where he immediately

faced a major leadership challenge. With the division badly scattered in the

night, he found himself in command of a detachment including another general, a

colonel, several captains, and one private. Paraphrasing Winston Churchill he

quipped, “Never in the history of human conflict have so many commanded so

few.”

Upon relieving Matthew Ridgway as division commander, the thirty-seven-year-old

Gavin became the youngest American major general since George Custer in the

Civil War. He assumed command of the “All Americans” in August and led the

Eighty-second in the ill-fated thrust to Nijmegen, Holland, during Operation

Market-Garden the following month. He was also in command during the Battle of

the Bulge and remained with the division until VE-Day.

In 1947 Gavin wrote an analysis of his combat experience,

published as Airborne Warfare. Much of his postwar service involved research

and development, but his ability eventually gained him the position as army

chief of staff. Gavin was concerned that President Dwight D. Eisenhower, his

former D-Day supreme commander, placed undue emphasis on America’s nuclear

arsenal at the expense of conventional forces. Unable to support what he felt

was an unwise policy, Gavin took the only honorable option and resigned his

position—an action almost unprecedented in the history of the U.S. Joint Chiefs

of Staff.

President John F. Kennedy appointed Gavin ambassador to

France, where he served from 1961 to 1963, but thereafter Gavin became a vocal

critic of American conduct of the Vietnam War. He felt that Kennedy’s

successor, Lyndon B. Johnson, would be unable to win the war and that American

vital interests were not directly threatened in any case.

In retirement Gavin wrote two more books—Crisis Now (1968),

a critical appraisal of America in Vietnam, and a biography, On to Berlin

(1978).