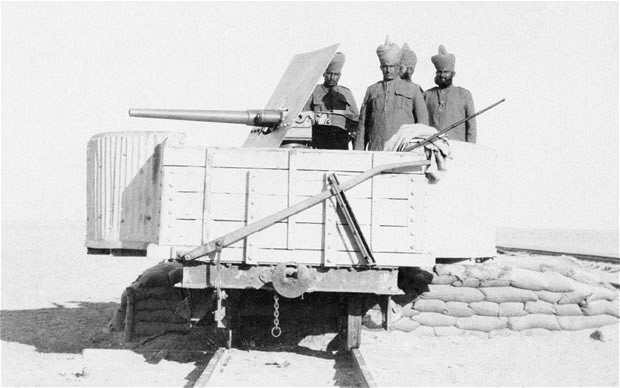

Basra: rail protection duty for India’s First World War soldiers.

Turkish Soldiers.

His calendar in the War Office in Whitehall showed that it

was Friday 18 December 1914. Sifting through the papers on his desk, Horatio,

Lord Kitchener, His Britannic Majesty’s Secretary of State for War, noted with

a grunt that today a formal British protectorate over Egypt had come into

force. So, Egypt was no longer part of the Ottoman Empire, that great rotting

relic of past Turkish glories still ruled from Constantinople. It was an empire

that included not just Turkey itself but the whole great swathe of Arabia,

stretching eastwards from the Suez Canal through Palestine and Syria, then

southwards taking in the whole of Mesopotamia and the desert vastness of the

Arabian peninsula, all the way to the Indian Ocean. For Kitchener, Arabia would

be the next great battlefield.

The Ottoman Empire had entered the Great War because of a

secret treaty signed with Germany on 2 August 1914. ‘So much for secrecy in the

Levant!’ thought Kitchener. What his network of spies and contacts throughout

Arabia could not find out could easily be bought for money or favours in

Constantinople, or in Baghdad.2 The Ottomans had entered the war when, after a

series of provocative incidents, on 28 October their navy had bombarded the

Black Sea ports of Odessa, Sebastopol, and Feodosia, belonging to their old

enemy Russia. The declaration of war by Russia, France, and Great Britain that

had followed on 4 November had been just a formality. The Ottoman response of

declaring a jihad, or holy war, against the Allies had produced singularly

little reaction among their own peoples, or among the Muslim troops and peoples

of the British and French empires. Instead, the British had landed the 6th

(Poona) Division from India unopposed at Basra, as the start of a painfully

slow advance up the river Tigris into Mesopotamia. Kitchener estimated that

Major General Sir John Maxwell’s 10th and 11th Indian divisions, now fully

formed in Egypt, should be enough to hold against a Turkish attack on the Suez

Canal. The much greater problem was that the Ottoman entry into the war had

severed the main line of supply and communications through the Black Sea

between the Russian Empire and its French and British allies. The British

government should have appointed him ambassador to Constantinople back in 1910

when they had the chance, Kitchener thought. He would have put an end to all

this nonsense with the Germans! Now, if the Black Sea route to Russia could be

reopened, he could put that right. He might even just save little Serbia,

hard-pressed though it was.

The formality of the British protectorate over Egypt was of

little matter to Kitchener. In reality, the British had controlled Egypt since

1882, including officering the Egyptian Army. Kitchener himself spoke Arabic,

and he had passed as an Egyptian when in disguise. In 1898 he had commanded the

combined British and Egyptian army that had smashed the Sudanese at Omdurman

and recaptured Khartoum. His active military service went back to 1870 and the

Franco-Prussian War, when he had volunteered as an ambulance corpsman with the

French. He had gone on to serve in most of the Levant, including Cyprus, which

he had mapped early in his career. After Omdurman, he had faced down a French

attempt at Fashoda to interfere in British rule over Sudan, risking a war with

France to do so. Sent to South Africa in 1899 alongside Field Marshal Lord

Roberts – little ‘Bobs’ who had died of old age and pneumonia only last month

visiting his beloved Indian troops in France – he had rescued the disastrous

British campaign against the Boers, ending the South African War of 1899–1902

by annexing the two Boer republics to the Crown.

Kitchener was now sixty-four years old. Having achieved his

last great ambition of commanding the Indian Army, in 1914 he was ending a

lifetime of imperial service with the post of consul general (effectively

governor) for Egypt. In Cairo, he had shared a palatial house with the

commander of the Egyptian Army, Major General the Honourable Julian Byng, an

aristocratic, tough, and experienced cavalryman known to all as ‘Bungo’. He was

Field Marshal Earl Kitchener of Khartoum and Broome; ‘K of K’ – and to the

British ‘K’ never meant anyone else, just as a century before ‘the Duke’ had

only ever meant Wellington. The double ‘K’ monogram adorned the stately home

that he had bought at Broome Park near Canterbury. Music hall songs were sung

about him, and china plates and mugs were sold with his face on them. No

British public figure was more popular, or more of an imperial legend.

Kitchener reached for the latest report from Maxwell’s

headquarters in Egypt, assessing the Ottoman threat to the Suez Canal. ‘The

only place from which a fleet can operate against Egypt is Alexandretta. It is

a splendid natural naval base.’ The report’s author was one Lieutenant T. E.

Lawrence. Always on the lookout for promising officers, Kitchener made a note

of the name. Alexandretta, that was the key. The small and almost unnoticed

Turkish port in the eastern Mediterranean was barely a hundred miles from

Cyprus (which the British had also just annexed from the Ottoman Empire, having

governed it in practice since 1878). Kitchener knew better than most just how

ramshackle Ottoman rule over Arabia had become. ‘A great deal depends on the

attitude of the Arab tribesmen,’ he had told Sir Edward Grey, the foreign

secretary, on 5 December, but Baghdad, five hundred miles from Basra along the

Tigris, was ‘an open city of 150,000 inhabitants – the garrison consists of a

weak division of probably bad troops’. Kitchener also knew all about the men

now ruling the Ottoman Empire, the ‘Young Turks’ of the 1908 palace revolution

who hoped to modernise their country. They cared far more about Turkey than

about Arabia, and increasingly they had come to accept that the vast expanses

of desert and palm trees might not be worth keeping in the future, even if they

could.

Kitchener hated politics and politicians even more than he

hated the cold of the London winter. Meetings of Prime Minister H. H. Asquith’s

new War Council were meant to decide strategy, but they were achieving nothing

because no one could agree on a plan. Despite the high political office which

he now held, Kitchener had insisted on keeping his job as consul general for

Egypt, and because he was a serving field marshal he was still eligible for a

military command. In July 1914 he had been in London only to receive his

earldom from King George V, and had been about to take ship for Egypt again.

But with war breaking out in Europe, Asquith had appealed to him to take the

War Office position, which had been vacant since April after a political fiasco

over Ireland which had nearly brought down the government, causing the fall of

Colonel J. E. B. ‘Galloper Jack’ Seeley as Secretary of State for War, and

nearly that of Winston Churchill as First Lord of the Admiralty. Asquith should

have given the War Office back to Lord Haldane, the brilliant political lawyer

who had created the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), the Territorial Force of

part-time peacetime volunteers, and much more besides. However, in the

atmosphere of August 1914, Haldane’s known admiration for – of all things –

German philosophy had ruled him out. The Chief of the Imperial General Staff

(the army’s professional head), Field Marshal Sir John French, had done the

decent thing in also resigning. But at least on the war’s outbreak French had

been given a proper job as commander of the BEF, which had been sent to the continent.

Kitchener grunted again, with approval: Johnny French was a difficult man to

work with, but he knew how to do his duty.

To Kitchener, Asquith’s appeal to take the War Office had

been direct and simple: in their hour of trial his country and its people once

more needed a hero, and he would never let them down. The problem was that,

despite the all-powerful Royal Navy, the British Empire had gone to war against

Germany without having an army to speak of. By continental European standards

the BEF was tiny. It had been badly knocked about before playing its

magnificent part in stemming the tide of the German invasion of France, and it

was crying out for reinforcements. The first troops of the Territorial Force,

who would ordinarily have needed months of training, were already in action

alongside the BEF regulars.

Kitchener had agreed with his new Cabinet colleagues that

the war would be long and hard, lasting perhaps three years. He had called for

a volunteer New Army, and both Britain and its empire had answered his call. By

the end of August one hundred thousand men had volunteered, and it would be

half a million by the start of the New Year. The recruiting posters were

everywhere, including Kitchener’s pointing finger telling the men that he

‘Wants You!’ The first of the New Army divisions – the ‘K-1’ divisions, they

were calling them – would be ready to be sent overseas by spring 1915.

Volunteers from Canada were arriving in Britain, and more from Australia and

New Zealand were training in Egypt, under the odd name of the Australia and New

Zealand Army Corps or ANZAC. It was a worldwide phenomenon unprecedented in

military history. Half a million men were volunteering to go to war, because K

of K had summoned them to do their duty.

In October, the hard-pressed BEF had also been reinforced by

four Indian Army divisions: an Indian Corps consisting of 3rd (Lahore) Division

and 7th (Meerut) Division, and an Indian Cavalry Corps consisting of 1st and

2nd Indian cavalry divisions. That had been mostly because of the work before

the war of General Sir Douglas Haig, now one of French’s subordinate commanders

with the BEF, from back when Haig had been Chief of Staff in India a few years

earlier. But putting Indian troops into a European war had been a stop-gap, and

the sooner they were out of France the better. Already, over seven thousand

Indian soldiers had been killed or wounded, in what one of them described

ominously as ‘this cold hell across the black water to which our British Sahibs

have sent us’. In Kitchener’s view, the complex balancing act that was the

British Empire did not include breaking faith with its Indian soldiers by

getting them killed by the Germans. Nor did it include those Indian soldiers,

many of whom revered their British officers, getting too close a look at the

darker realities of British society.

Although Kitchener did not admit to mistakes, he also knew

that appointing General Sir Horace Smith-Dorrien as Johnny French’s other

subordinate commander had been an error: the two men just did not trust each

other. The problem was that Sir John French was in the wrong job. His

replacement as Chief of the Imperial General Staff, General Sir Charles

Douglas, had died from overwork in October while trying to make the New Armies

a reality. Kitchener had chosen a pliable nonentity, Lieutenant General James

Wolff Murray, for his successor. At least Kitchener had an old and trusted

subordinate, General Sir Ian ‘Johnnie’ Hamilton, helping with recruiting at the

War Office. Hamilton was also the British Army’s expert on amphibious landings,

having pioneered the techniques and training before the war.

Kitchener re-read the draft of a letter he was writing to

Johnny French at BEF headquarters: ‘the German lines in France may be looked on

as a fortress that cannot be carried by assault and also cannot be completely

invested, with the result that the lines may be held by an investing force

whilst operations proceed elsewhere.’ Kitchener had seen too often what

happened when under-trained and badly equipped troops were thrust into action.

It would be at least two years before his New Army divisions were ready to beat

the Germans on the Western Front. So before then, what was the best use of

them, and of any other troops that he could find?

There was the last of the good divisions that Kitchener had

formed by bringing home the regular battalions from all over the empire, the

29th Division. Winston Churchill had contributed a Royal Naval Division made up

of sailors and marines, and the irrepressible Churchill would be bound to get

involved in the fighting somehow. In October he had led the Royal Naval

Division on a brief and unsuccessful excursion to preserve Antwerp from the

Germans, and had even tried to resign from the Cabinet if only Asquith would

give him command of the troops there! With a Cavalry Corps of three divisions

already serving with the BEF – with old Bungo in command of the new 3rd Cavalry

Division, Kitchener noted – an Indian Cavalry Corps of two divisions was not

going to be of much use. The Western Front would be dominated by artillery and

combat engineering for the foreseeable future. So, where would cavalry be most

useful?

Kitchener thought about his days as commander-in-chief in

India, when Haig as his inspector general of cavalry had introduced the new

tactics and methods that he and Johnny French had pioneered in Britain. Unlike

any other cavalry in the world – except for the Japanese and the Americans, and

they didn’t matter – the cavalry of the British Empire were equipped with the

same rifles as the infantry, and were trained to charge rapidly to capture a

position and then hold it dismounted. Even more importantly, years of hard

experience campaigning in the desert and the veldt meant that British Empire

troopers knew how to keep the horses alive and fit for battle in the most

unpromising terrain.

Generals, soldiers, sailors, plans – it was all starting to

fit together. Britain did not even have one proper army, but now by a conjuring

trick Kitchener would create two. What if he took command of the Indian Corps

and Indian Cavalry Corps taken from the Western Front, plus the Indian and

ANZAC infantry in Egypt, the Royal Naval Division, and the crack 29th Division?

Against the weak Ottoman Turkish divisions spread thinly throughout Arabia that

was the beginnings of a powerful force. For the time being, Kitchener’s job in

Whitehall was done. The best service he could give his country now was to

resign, go back to Egypt and beat the Turks, opening up the Black Sea route to

Russia. Then he could return in a year or so, in triumph as so often before, to

take command in the field of his New Army divisions, which by then would be well

enough trained to take on the Germans, and so win the war. But it all hinged on

the amphibious landings, on the cavalry, and on Alexandretta.

Alexandretta

On the very day that Kitchener was deliberating, 18 December

1914, at Alexandretta itself events were taking place that would convince Prime

Minister Asquith and the War Council of the wisdom of his plan. Frightened

officials in Alexandria were informed that a British warship had been sighted

out to sea just to the north of the port, and had landed an armed party of

sailors. The British had torn up the rail track, isolating Alexandretta from

Constantinople, and derailed an arriving train. The officials, with their small

military garrison and no warships, had hardly expected the Great European War to

reach as far as them. The artillery pieces from Alexandretta’s obsolete

fortress had been dismounted at the war’s start and sent elsewhere. The

strongest Ottoman forces, the fourteen divisions of the 1st and 2nd armies,

were on the European side of the Bosphorus in Thrace. They were waiting for an

expected attack by Bulgaria, which had been the main enemy in the First Balkan

War of 1912–13. Bulgaria had then been attacked by its own allies, Serbia and

Greece, in the Second Balkan War of 1913, enabling the Ottomans to seize back

Adrianople, but the threat was still there. The best quality Ottoman formation,

the 5th Army, of six divisions, was guarding the southern approaches to

Constantinople including the Gallipoli peninsula, in case the British or French

attempted to break through the Dardanelles by sea. Constantinople’s attention

was fixed on the Russian Caucasus, where the 3rd Army of eleven divisions and

two cavalry divisions was launching its great offensive at Sarikamis against

the Russians. This was an ambitious encirclement planned along impeccable

German General Staff lines, and modelled on the recent German triumph at

Tannenberg in August.

By far the weakest and least well-equipped Ottoman formation

was the 4th Army under Djemel Pasha (with the German Colonel Werner von

Frankenberg as his Chief of Staff). This had only XII Corps of two divisions in

Mesopotamia, and VIII Corps of five divisions in Palestine and Syria, mostly

facing the Sinai desert. That left only 27th Division at Damascus and 23rd Division

at Aleppo. The damning postwar assessment by Paul von Hindenburg (in 1914

commander of German forces in Eastern Europe) was that ‘The protection of the

Gulf of Alexandretta was entrusted to a Turkish Army which contained scarcely a

single unit fit to fight.’

Kitchener’s eyes were drawn to Alexandretta because, along

with its importance as a harbour, Alexandretta was also the hinge of Ottoman

strategic communications by land between Turkey and Arabia, including

Mesopotamia and the Levant. Alexandretta was the southern terminus of a minor

branch of the incomplete main rail line from Constantinople. In 1914 the main

line ran with some breaks through to Muslimie Junction, only a few miles north

of Aleppo. At this critical junction the line divided, with one branch going

south through Damascus and Amman, with a further branch through Jerusalem, and

the other going east to the railhead at Ras-el-Ayn, the gateway to Mesopotamia,

where far to the south the line joining Samarra and Baghdad had only just opened

that year.

North of Alexandretta there were two critical gaps in the

main rail line, totalling about twenty-five miles, through the Taurus and

Amanus mountains, where the route was impassable to wheeled transport. Rather

than negotiate the Amanus gap with pack animals, it was actually faster for

travellers and supplies to be routed down the Alexandretta branch line. They

would then strike out eastwards across the lower slopes of the Amanus range to

the open plain, covering the sixty or so miles inland to Muslimie Junction

across country. With all the gaps and problems of the line, and the bureaucracy

of a diverse and dissolute empire, military reinforcements and supplies from

Constantinople could take two months to reach Baghdad or Jerusalem. Enver

Pasha, the Ottoman minister of war, confided to his German allies that ‘My only

hope is that the enemy has not discovered our weakness at this critical spot.’

Enver’s hope was in vain. British war plans going back to

1906 included an attack from Egypt supported by amphibious landings at Haifa or

Alexandretta, accompanied by possible support from the Arab tribes. But the

British understood that the greatest Ottoman fear, other than a renewed attack

from the west by Bulgaria or the other Balkan states, was that the British

could use their formidable command of the sea to attack Constantinople through

the Dardanelles narrows. British plans before the war had considered a landing

on the Gallipoli peninsula to force a passage through the Dardanelles narrows

and on to Constantinople, but only as part of a much larger campaign involving

several fronts. Even at worst for the British, a landing at Gallipoli would

provoke a strong Ottoman response, tying down more of their best troops.

The first British warship to appear off the coast at Alexandretta – the appearance on 18 December that so panicked the town’s officials – was the light cruiser HMS Doris, one of a small naval flotilla with seaplanes based in Egypt and sent out from Alexandria to gather intelligence on the Ottoman dispositions. Next day, the Doris landed another shore party which drove in a Turkish patrol, blew up a railway bridge, wrecked a railway station, and cut the telegraph wires. The ship’s captain also sent an ultimatum, backed by the threat of a naval bombardment from the Doris’s 6-in guns against which Alexandretta had no defence, that its officials should surrender all warlike stores and engines.

War Plans and Strategies 1914: The Alexandretta Scenario Part I: Strategic Origins of the Idea