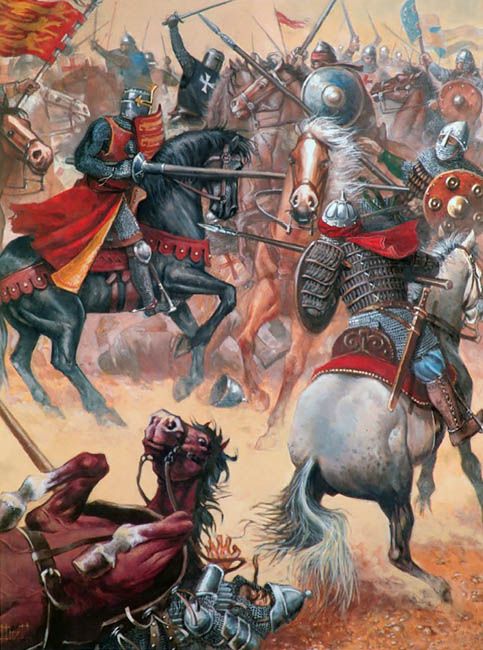

“Richard the Lionheart, Battle of Arsuf, 1191” Justo Jimeno Bazaga

In late summer 1191 King Richard I of England prosecuted a

remarkably controlled, ruthlessly efficient march south from Acre to Jaffa,

subjecting Saladin to a humiliating, if not crushing, defeat along the way.

Since his arrival in the Holy Land, the Lionheart had galvanised the Third

Crusade; no longer mired and inert in the northern reaches of Palestine, the

expedition now seemed poised on the threshold of victory. Success depended on

momentum – only immediate and resolute action would preserve the brittle

Frankish coalition and maintain pressure on a faltering enemy. But just when

focused commitment to a clear military goal was needed, Richard hesitated.

Around 12 September 1191, just a few days after reaching

Jaffa, worrying reports from the south began filtering into the crusader camp.

Saladin, it was said, had moved on Ascalon and even now was razing the

Muslim-held port to the ground. With these rumours stirring up a mixture of

incredulity, horror and suspicion, the king dispatched Geoffrey of Lusignan

(who had now been appointed titular count of the region) and the trusted knight

William of L’Estang to investigate. Sailing south, they soon caught sight of

the city, and, as they drew closer, a scene of appalling devastation revealed

itself. Ascalon was awash with flame and smoke, its terrified populace

streaming away in forced evacuation while the sultan’s men swarmed over the

port’s mighty defences, ripping wall and tower asunder.

This grave spectacle was the product of Saladin’s newly

resolute approach to the war. Still smarting from his humiliating defeat at

Arsuf, the sultan had assembled his counsellors at Ramla on 10 September to

re-evaluate Ayyubid strategy. Having tried and failed to confront the crusaders

head-on during their march south from Acre, Saladin decided to adopt a more

defensive approach. If Richard could not be crushed in open battle, then

drastic steps would be taken to halt his advance – a scorched-earth policy to

hamper Frankish movement, involving the destruction of key fortresses. The

critical target was Ascalon, southern Palestine’s main port and the stepping

stone to Egypt. If the Franks captured the city intact then the Lionheart would

have the perfect bridgehead from which to threaten Jerusalem and the Nile

region. Saladin realised that he lacked the resources to fight a war on two

fronts and, prioritising the protection of the Holy City, ordered that

Ascalon’s walls be razed to the ground. This cannot have been an easy decision

– the sultan was said to have remarked, ‘by God I would prefer to lose all my

sons rather than demolish a single stone’ – but it was necessary. Time was

pressing, for if Richard marched on he might yet seize the port. Saladin

therefore sent al-Adil to watch over the crusaders at Jaffa, and then raced

south with al-Afdal to oversee the dreadful labour, driving his soldiers to work

at a furious pace, day and night, fearful of the Lionheart’s arrival.

When Geoffrey and William brought news of what they had seen

to Jaffa, King Richard still had a chance to act. Throughout the late summer he

had been deliberately evasive about his objectives, but now a definite decision

had to be made. To the Lionheart, the choice seemed clear: the seizure of

Ascalon was the logical next step for the crusade. As a general he recognised

that, to date, the expedition’s achievements had been dependent upon naval

superiority. While the crusade continued to hug the coastline, Latin domination

of the Mediterranean could stave off isolation and annihilation by offering a

lifeline of supply and reinforcement. So far, the Christians had not truly

fought the Third Crusade in enemy territory; once they marched inland, the real

battle would begin. Ascalon’s seizure and refortification promised to

destabilise further Saladin’s hold over Palestine, creating a secure coastal

enclave, while keeping Richard’s options open for an eventual assault on

Jerusalem or Egypt.

Richard arrived in Jaffa apparently expecting that, as king

and commander, his will would be obeyed; that the march south could continue,

almost without pause. But he had made a serious miscalculation. As a species of

war, the crusade was governed not merely by the dictates of military science,

nor by notions of politics, diplomacy or economy. This was a mode of conflict

underpinned by religious ideology – one that relied upon the overwhelming and

imperative devotional allure of a target like Jerusalem to create unity of

purpose within a disparate army. And for the vast majority of those within

Richard’s amalgamated crusading host, marching south from Jaffa was tantamount

to walking past the doorway to the Holy City.

At a council held outside Jaffa in mid-September 1191, the

Lionheart was confronted by this reality. Despite his best efforts to press for

an attack on Ascalon, a large number of Latin nobles resisted – among them Hugh

of Burgundy and the French – arguing instead for the refortification of Jaffa

and a more direct strike inland towards Jerusalem. In the end, as one crusader

put it, ‘the loud voice of the people prevailed’ and a decision was made to

stay put. Richard seems not to have recognised it at the time, but he had

failed a critical test. The events at Jaffa exposed an ominous deficiency in

his skills as a leader. The Lionheart had been well schooled in the affairs of

war since childhood; since 1189 his skills and authority as a king had blossomed.

But, as yet, he had not grasped the reality of crusading.

With the decision to halt at Jaffa, the crusade lost

impetus. Work began to rebuild the port and its defences, even as Saladin

completed Ascalon’s destruction. Crusaders, shattered by the horrors of the

march from Acre, now basked in the sudden break in hostilities. Among the

constant flow of supply ships, vessels packed with prostitutes soon began to

appear. With their arrival, bemoaned one Christian eyewitness, the army was

again polluted by ‘sin and filth, ugly deeds and lust’. As days turned to

weeks, even the will to press on to the Holy City faltered and the expedition

started to fragment. Some Franks actually sailed to Acre to enjoy more

luxurious comforts, and eventually Richard had to travel north in person to

goad these absentees back into action.

On the road to

Jerusalem

In the end, the Third Crusade remained stalled around Jaffa

and its environs for the best part of seven weeks. This delay gave Saladin time

to extend his scorched-earth strategy, demolishing the network of

fortifications running from the coast inland to Jerusalem. Richard spent much

of October 1191 reassembling his army and, only in the last days of that month,

with the normal fighting season drawing to a close, did the expedition begin to

advance on Jerusalem. It now faced a challenge unlike any encountered by

previous crusades. Back in 1099, the First Crusaders had marched on the Holy

City largely unopposed, and in their subsequent siege, arduous though it was,

the Franks had encountered a relatively small, isolated enemy force. Now,

almost a century later, the Latins could expect to meet far sterner resistance.

Saladin’s power may have weakened in the years since 1187,

but he still possessed formidable military resources with which to harass and

oppose every step of a Christian approach on the Holy City. And should the

crusaders reach Jerusalem, its actual conquest presented manifold difficulties.

Protected by a full garrison and stout physical fortifications, the city’s defences

would be all but insurmountable, while any besieging army would undoubtedly

face fierce counter-attacks from additional Muslim forces in the field. More

troubling still was the issue of supply and reinforcement: once the Third

Crusade left the coast behind, it would have to rely upon a fragile line of

communication back to Jaffa; if broken, Richard and his men would face

isolation and probably defeat.

The Lionheart’s primary aim in the autumn of 1191 was the

forging of a reliable chain of logistical support running inland. The main road

to Jerusalem crossed the coastal plain east of Jaffa, through Ramla to Latrun,

before arcing north-east to Beit Nuba in the Judean foothills and then winding

east up to the Holy City (although there were alternatives, such as the more

northerly route via Lydda). In the course of the twelfth century, the Franks

had built a string of fortresses to defend the approaches to Jerusalem. Many of

these had been controlled by the Military Orders, but all had fallen to Islam after

Hattin.

Saladin’s recent shift in strategy had left the road ahead

of the crusaders in a state of desolation. Every major fortified site –

including Lydda, Ramla and Latrun – had been dismantled. On 29 October Richard

marched on to the plains east of Jaffa and began the painstakingly slow work of

rebuilding a string of sites running inland, starting with two forts near

Yasur. In military terms, the war now devolved into a series of skirmishes.

Marshalling his forces at Ramla, Saladin sought to hound the Franks, impeding

their construction efforts while avoiding full-scale confrontation. Once the

advance on Jerusalem began, the Lionheart frequently threw himself into the

thick of these running battles. In early November 1192, a routine foraging

expedition went awry when a group of Templars were attacked and outnumbered.

When the news reached him, the king rode to their aid without hesitation,

accompanied by Andrew of Chauvigny and Robert, earl of Leicester. The Lionheart

arrived ‘roaring’ with bloodlust, striking like a ‘thunderbolt’, and soon

forced the Muslims to retreat.

Latin eyewitnesses suggest that some of the king’s

companions actually questioned the wisdom of his actions that day. Chiding him

for risking his life so readily, they protested that ‘if harm comes to you

Christianity will be killed’. Richard was said to have been enraged: ‘The

king’s colour changed. Then he said “I sent [these soldiers] here and asked

them to go [and] if they die there without me then would [that] I never again

bear the title of king.”’ This episode reveals the Lionheart’s determination to

operate as a warrior-king in the front line of conflict, but it also suggests

that, by this stage, he was taking risks that worried even his closest

supporters. It is certainly true that there were real dangers involved in these

skirmishes. Just a few weeks later, Andrew of Chauvigny broke his arm while

skewering a Muslim opponent during a scuffle near Lydda.

Talking to the enemy

Bold as Richard’s involvement might have been in these inland

incursions, his martial offensive was just one facet of a combined strategy.

Throughout the autumn and early winter of 1191 the king sought to use diplomacy

alongside military threat, perhaps hoping that, when jointly wielded, these two

weapons might bring Saladin to the point of submission, forestalling the need

for a direct assault on Jerusalem.

In fact, the Lionheart had reopened channels of

communication with the enemy just days after the Battle of Arsuf. Around 12

September he sent Humphrey of Toron, the disenfranchised former husband of

Isabella, to request a renewal of discussions with al-Adil. Saladin acceded,

giving his brother ‘permission to hold talks and the power to negotiate on his

own initiative’. One of the sultan’s confidants explained that ‘[Saladin]

thought the meetings were in our interest because he saw in the hearts of men

that they were tired and disillusioned with the fighting, the hardship and the

burden of debts that was on their backs’. In all probability, Saladin was also

playing for time and seeking to garner information about the enemy.

In the months to come, reliable intelligence proved to be a

precious commodity, and spies seem to have infiltrated both camps. In late

September 1191 Saladin narrowly averted a potentially disastrous leak when a

group of eastern Christians travelling through the Judean hills were seized and

searched. They were found to be carrying extremely sensitive documents –

letters from the Ayyubid governor of Jerusalem to the sultan, detailing

worrying shortages of grain, equipment and men within the Holy City – which

they had intended to present to King Richard. Meanwhile, to furnish a regular

supply of Frankish captives for interrogation, Saladin engaged 300 rather

disreputable Bedouin thieves to carry out night-time prisoner snatches. For

Latin and Muslim alike, however, knowledge of the enemy’s movements and

intentions was always fallible. Saladin, for example, was apparently informed

that Philip Augustus had died in October 1191. Perhaps more significantly, the

Lionheart persistently overestimated Saladin’s military strength for much of

the remainder of the crusade.

Throughout autumn and early winter 1191, Richard eagerly

maintained a regular dialogue with al-Adil, and, to begin with at least, this

contact seems to have been hidden from the Frankish armies. In part, the king

must have been driven to negotiation by the rumour that Conrad of Montferrat

had opened his own, independent, channel of diplomacy with Saladin. As always,

the Lionheart’s willingness to discuss avenues to peace with the enemy did not

indicate some pacifistic preference for the avoidance of conflict. Negotiation

was a weapon of war: one that might beget a settlement when combined with a

military offensive; one that would certainly bring vital intelligence; and,

crucially in this phase of the crusade, one that offered an opportunity to sow

dissension among the ranks of Islam.