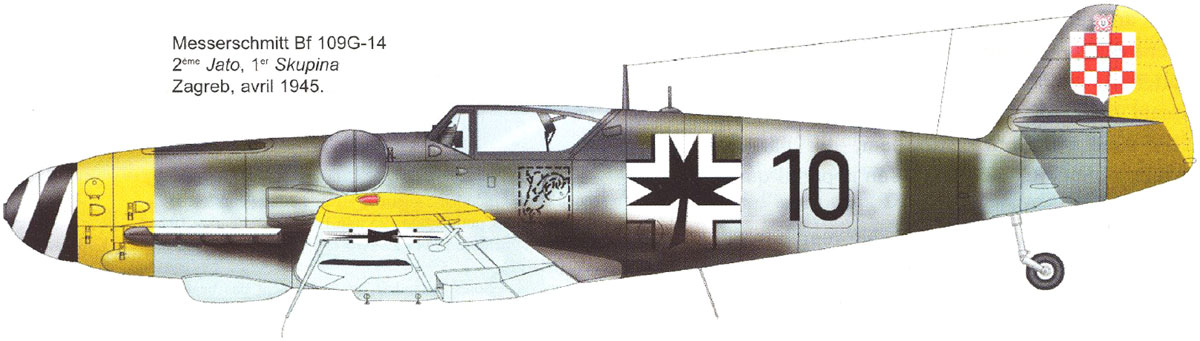

Messerschmitt Bf.109G-14 Unit: 2. Lovacko Jato, 1. Zrakoplovna Skupina Zagreb-Lucko,

April 1945. On 16th April 1945 Josip Cekovic defected to Falconara region

(Italy) 12 kilometers westward of Ancona. This airplane was captured by

Americans.

Dornier Do.17Z-2 Unit: 19. Bombardersko Jato, 1. Zrakoplovna Skupina Zagreb,

spring 1945.

Breguet Br.19-8 Unit: 6 Sqn ‘Anti-guerilla’, 2 Group Circa 1943.

Macchi MC.202 Serie XII Unit: 2./Kro.JGr 1 Pilot – CO of 2./Kro.JGr 1

Capt (later Maj.) Josip Helebrant.

From late August through early September 1942, bitter

fighting along the Novorossiysk front involved the 15th Koatische. /JG as never

before, with its pilots averaging 20 escort missions every day. On September 3,

Starc and Oberfelclwebel (Sergeant Major) Stjepan Martinasevic were flying

cover for an Fw.189, when they were bounced by eight Ratas. Two of the attackers

were damaged and the rest driven off. The twin-engine, twin-boom, three-place

Focke-Wulf-189 was the war’s finest reconnaissance aircraft, able to execute a

circle so tight that Allied interceptors could not follow it. Although armed

with five 7.92mm MG 17 machine-guns, more often than not, the Uhu, or

“Owl; simply out-ran its pursuer. The Fw.189 was also extraordinarily

rugged, sometimes returning to base from the thick of combat minus an entire

tail.

Three days after escorting this “Flying Eye” of the

German Army, Starc and Helebrant were assigned anti-shipping duty over the

Black Sea. There, they strafed a 100-ton tanker, blasting it with concerted

cannon fire, until the vessel erupted into a flaming inferno, capsized, and

sank in minutes. On September 8, Helebrant was back over the Novorossiysk front

with Martinasevic, when they intercepted a reconnaissance aircraft escorted by

11 Chaika fighters. Martinasevic dispatched a Soviet “Seagull;’ then

joined Helebrant in destroying the Polikarpov R-5. As some indication of Soviet

military obsolescence, this 680-hp, wood double-decker from 1930 was the

standard reconnaissance model of the Red Air Force, which equipped over 100 of

its regiments with the antique airplane into 1944.

What the Russians lacked in quality, they strove to

compensate with quantity, as four Croatian pilots observed while patrolling the

road between Gelendzhik and Novorossiysk. During their clash with 5 Chaikas and

14 Ratas, Oberstleutnant Dzal destroyed one of either type, while Fähnrich

(Officer Candidate) Tomislav Kauzlaric shot down an 1-16. On October 24,

Helebrant and Starc each brought down a pair of Lavochkin fighters over the

Tuapse area, raising their unit’s score to 150 confirmed “kills:” In

November, the pilots were returned to Croatia for extended rest after a full

year of virtually non-stop flight operations. These comprised 3,698

sorties-2,460 of them combat missions-for the confirmed destruction of 178

enemy aircraft, plus 33 “probables.” Six Croatian pilots had been lost

in action, together with five ground crew men in Soviet raids.

During mid-February, the men of 15th

Kroatische./Jagclgeschwacler 52 returned to the Eastern Front in the company of

fresh recruits and new planes. But the situation had changed dramatically over

the previous three months. The Axis initiative that had rolled irrepressibly

across Russia since the first day of Operation Barbarossa had stopped at

Stalingrad, where Croatian casualties were very heavy. And U.S. aid to the

Soviets was now apparent in the appearance of American aircraft. On April 15,

1943, Oberleutnant Mato Dukovac fired on a Bell P-39 fighter that “flamed

like a torch before abruptly falling away.”

The Aircobra’s streamlined, aerodynamically efficient design

had been occasioned by placement of a 1,200-hp Allison V-1710-85, liquid-cooled,

V-12 engine behind the cockpit. This peculiar arrangement enabled a 37-mm M4

cannon to fire 30 rounds of high-explosive ammo through the propeller hub at

the rate of 140 rounds per minute. It was supplemented by a 12.7-mm machine-gun

installed in each wing; two more were mounted in the upper engine cowl.

Regardless of this formidable armament, the rear-mounted engine proved to be

vulnerable to attacks from above and behind. Almost any hit on the fuselage

from an attacking enemy fighter was virtually guaranteed to disable the cooling

system, destroying the engine. In crash-landings, the pilot was liable to be

crushed by the hot, heavy engine falling forward on his back.

The all-metal fighter’s unconventional layout allowed no

space in the fuselage for a fuel tank, which was transferred to a necessarily

smaller tank in either wing, thereby restricting the P-39’s operational radius.

Moreover, its single-speed supercharger confined optimal performance to beneath

12,000 feet, a serious limitation, as modern aerial combat took place at

increasingly higher altitudes. By 1942, virtually all bombers carried out their

runs far beyond the Aircobra’s reach. Performance was further compromised by

265 pounds of armor plating, which was appropriate for a ground-attack role,

but detracted from Bell’s original fighter conception. An innovative tricycle

undercarriage and hinged “automobile doors” on either side of the

cockpit contributed to the aircraft’s unorthodox design.

Despite its numerous drawbacks, the P-39 was just 10 mph

slower than the Messerschmitt-109, handled very well, and was the best fighter

available to Soviet pilots, who referred to it affectionately as Kobrastochka,

“dear little cobra:” Aleksandr Pokryshkin, the Allies’ second highest-scoring

ace, accounted for 58 Axis aircraft in a P-39, the highest score ever gained by

any pilot with a U.S.-built aircraft. The 4,773 Aircobras President Roosevelt

sent to beleaguered Soviet pilots critically helped them make up the severe

losses they suffered since June 1941.

Five days after Dukovac’s first encounter with an American

Kobrastochka, he was escorting German Stuka dive-bombers and Ju.88

medium-bombers in the company of three other Gustavs, one piloted by the

redoubtable Cvitan Galic, when they ran into 25 Soviet fighters and gigantic

flying boats. In the engagement that ensued, Dukovac downed a LaGG-3, as Galic

went after a Chyetverikov MDR-6, with its 63-foot, 7.75-inch wingspan. Only 27

of the big, twin-engine, highwing flying boats had ever been built, so Galic

felt privileged to claim this rara avis, which disintegrated in flames toward

Novorossiysk. Continuing escort duty produced more residual “kills”

on May 8, when Dukovac and his wingman, Felclwebel Bozidar Bartulovic, each

destroyed a LaGG-3 while protecting a Fieseler Storch.

The Fi.156 was famous for its unprecedented STOL

characteristics, making it the war’s outstanding liaison and medivac aircraft.

Its very low landing speed combined with a long-legged undercarriage containing

oil and spring shock absorbers that compressed about 18 inches on landing

enabled the “Stork” to set down in a variety of otherwise impossible

terrain. It could hover in place, almost like a helicopter, or even fly

backwards against a head wind. Under normal conditions, the Fi.156 took off in

less than 150 feet and landed in 60. Wings could be folded back along the

fuselage, allowing it to be transported by trailer, aboard covered trains, or

towed behind a vehicle. Flying their high-performance Messerschmitts, the

Croatian pilots found escorting the 100-mph Storch a challenging, but rewarding

experience.

Despite the debacle at Stalingrad, Axis morale held firm.

There was no rout, and the Eastern Front stood badly dented, but unbroken.

Positions from the vicinity of Leningrad in the north, down through Smolensk

and Taganrog to the Sea of Asov in the south stiffened, frustrating all Soviet

attempts to break through, while the Red Air Force lost more than 2,000

warplanes in combat above Kuban. These defensive successes were generally

regarded as prelude to a renewed Wehrmacht offensive that would regain the initiative

in summer. But news of the Italo-German loss of North Africa in early May

struck some observers as the Axis death knell. On the 14th, two pilots of the

15th Koatische.I JG 52 defected to the Soviets, setting down their Bf.109s

behind enemy lines at Byelaya Glina airfield, northeast of Krasnar.

A month and one day later, another Croatian pilot landed at

Byelaya Glina. Over the next two years, defections took place in direct ratio

to the decline of Axis fortunes. While much has been made of them by Allied

historians, the actual number of deserters from the unit represented a small

fraction of its total strength. Most who defected simply wanted to end the war

on the winning side, and were largely indifferent to ideological concerns.

Those who did give political consequences any thought had been deceived by

Communist propaganda promises of a free Croatia or, in the case of Slovenian

airmen, an independent Slovenia. These trusting souls were to be sadly

disappointed with the postwar fate of Eastern Europe, and many fled to the West

after the Iron Curtain fell on their respective homelands.

A case in point was the first Balkan airman, Nikola Vucina,

who flew over to the Soviets on May 4,1942. Horrified by the bloodshed and

slavery visited upon Yugoslavia by the Red Army, he fled in an ancient

Polikarpov Po-2 Kukuruznik (“Corn”) trainer to Italy in 1946.

Mato Dukovac, Croatia’s top-scoring ace with 45 kills, lived

to regret his defection by flying to Italy in another biplane, a stolen British

De Havilland “Tiger Moth;’ less than a year after his September 20, 1944

desertion. Dukovac became increasingly anti-Jewish after his wartime

experiences, so much so, he volunteered to fight the newly created state of

Israel as a captain in the Syrian Air Force, flying American T-6 Texan trainers

outfitted with ground-attack rockets and 110-pound bombs during the

Arab-Israeli Conflict of 1948.

The attitude of most Croatian pilots was summarized in June

1944, when one of their officers, Oberst Franjo Dzal, offered them the

alternatives of fighting on, going to Germany for advanced training, or joining

the partisans. According to Savic and Ciglic, “His words were greeted by

whistles and shouts of disapproval’s”

The Croatian airmen continued to enjoy the clear-cut

superiority of their Bf.109Gs throughout most of 1943. In early November,

however, they began encountering growing numbers of an opponent with serious

claims on the Messerschmitt’s predominance. This was the Lavochkin La-5, the

Soviets’ first and only up-to-date fighter. While its performance fell off

above 12,000 feet, the La-5 excelled at lower altitudes. It executed a smaller

turning radius and higher roll rate than the German Gustav. Ivan Kozhedub, the

leading Red Air Force ace, scored most of his 62 kills flying the La-5. With

more of these dangerous machines filling Russian skies, outnumbered pilots of

the 15th Kroatische. /JG 52 were hard pressed.

On November 7, Unteroffizier (Senior Corporal) Vladimir

Salomon was shot down by a combination of Aircobras and La-5s. Successfully

bailing out of his stricken Bf.109, he froze to death after parachuting into

the Sea of Azov. Two weeks later, Felclwebel Zdendo Avdic and Dukovac were

battling six LaGG-3s, when Avdic received a particularly painful wound in the

right arm. He was horrified to observe that his severed hand still gripped the

control column, which he manipulated with his left to make a perfect landing,

albeit barely conscious from a prodigious loss of blood, five miles inside

friendly territory. German grenadiers carried Avdic to a field hospital, where

he eventually recovered.

By then, the unit had been stationed at Karankhut airfield,

where adverse weather conditions grounded its pilots until early 1944, save on

rare occasions. When conditions cleared in February, they faced greater numbers

of enemy aircraft-many of them La-5s and P-39s-than ever before encountered.

Flying against impossible odds, the squadron was decimated, and the 15th

Kroatische./JG 52 disbanded, its survivors returning to Croatia in mid-March.

During the previous five months, flying through foul weather and against

overwhelming adversaries, five of the airmen were killed, and four had been

seriously wounded. But between them they scored 77 confirmed “kills”

and 8 “probables.”

In July, survivors joined the newly formed Hrvatska

Zrakoplovna Skupina, the Croatian Air Force Group, for homeland defense against

increasing incursions by Anglo-American bombers. The HZS was also no less

preoccupied with quashing the various Communist and nationalist insurgent

groups running rampant through the countryside. Fighting these rebels was

nothing new. As long before as June 26, 1941, pilots of its predecessor, the

Air Force of the Independent State of Croatia (Zrakoplovstvo Nezavisna Drava

Hrvatska), had carried out the earliest anti-partisan raids in Herzegovina and

suffered its first loss the following day, when an aged Potez Po-25 biplane was

brought down by rebel ground-fire.

Increasingly fortified with Soviet arms, supplies, and

propaganda, the Yugoslav underground movement grew steadily throughout 1941,

when 15 aircraft were lost to the partisans. In June 1942, they absconded with

a pair of French bombers-a Brequet-19 and Potez Po-25-from the Zegreb

headquarters. The Yugoslav Royal Air Force had purchased its first Breguet-19s

as far back as 1924, thereafter license building another 300 examples. Most of

these were destroyed during the German Blitzkrieg of April 1941, but enough

survived to flesh out the new Croatian Air Force. While randomly machine-gunning

the residents of Banja Luka, the bandit Breguet was brought down by flak

outside the village of Kadinjani. Its pilot committed suicide, while his gunner

was shot trying to escape.

ZNDH commanders were deeply alarmed by the brazen theft of

this World War I-style sesquiplane with cloth-covered wings and open cockpits,

and spent all their energies searching for its companion. Meanwhile, the

elderly Po-25 raided four towns in as many days, successfully eluding all

efforts to intercept it, until the pokey Potez was finally spotted by the

Luftwaffe pilot of a Focke-Wulf Fw.58. On July 7, his twin-engine Weihe

(“Harrier”) trainer doubling as a reconnaissance-attack plane used

its two MG 15 machine-guns to shred the stolen aircraft while parked near Lusci

Palanka.

In summer, the ZNDH mounted its first, concerted offensive

against the burgeoning insurgency with warplanes left over from the defeated

Royal Yugoslav Air Force. All were antiquated and worn out, but the most useful

among them were 7 Avia BH-33Es remaining from 38 destroyed while resisting the

invading Germans, back in 1941. The 1927 Czech biplane’s physical appearance

was somewhat strange for its upper wing, being shorter, for reasons never

entirely understood, than the lower. An otherwise reliable, if entirely mediocre

fighter, the Vickers machine-guns and low speed provided by its 580-hp Skoda L

engine made it ideal for strafing partisans. They were themselves hamstrung by

conflict between the Soviet-backed Narodnooslobodilacka Vojska Jugoslavije

(“People’s Liberation Army of Yugoslavia”) and royalist-nationalist

Chetniks, from the Serbian word seta for a “military company.”

According to Savic and Ciglic, “Often, groups of

insurgents were at each others’ throats, rather than attacking their common

enemy. There was even collaboration with the Axis on both sides.”

Shortly after the Wehrmacht conquest, the several resistance

movements began to coalesce into a general insurgency until the Chetnik leader,

Draza Mihailovic, realized that Josip Tito’s NVJ only wanted to “burn the

country and the old order to the ground to better prepare it for Communism.

This is the fight that the Communists wage, a fight which is directed by

foreign propaganda with the aim of systematically annihilating our nation:”

He was likewise mistrustful of the Anglo-Americans, whose “sole aim was to

win the war at the expense of others:”‘ Favorably impressed by Germany’s

invasion of the USSR, Mihailovic hoped to create a Greater Serbia in the manner

of the Independent State of Croatia, when he learned that Hitler’s postwar

intentions for the former Yugoslavia was its division along ethnic lines into

various, similarly autonomous states. In the resulting civil war between

Communists and Chetniks, the Croatian airmen sought to annihilate them both.

Mussolini sent their ZNDH its first modern aircraft in the

form of 10 Fiat G.50 fighters, during late June 1943. Although eclipsed by

other designs by then, the Freccia, or “Arrow,” could still intercept

enemy bombers or ground-attack insurgent forces with success. Following the

Duce’s overthrow in September, the ZNDH received something of a windfall when

60 Italian aircraft of various types were found at Mostar and Zadar airfields.

They included three “Arrows” and six Fiat CR.42 biplanes no longer

fit for aerial combat, but very effective in anti-partisan warfare.

While the rebels lacked any aircraft of their own, they took

their toll on ZNDH men and machines through ground-fire and espionage. On

October 7, the Commanding Officer of 1. Air Group, Mato Culinovic, an ace with

a dozen “kills” to his credit, perished with his crew aboard a

Dornier Do.17K medium-bomber that exploded while attacking insurgent forces

west of Zagreb; saboteurs had installed a detonator activated when the bay

doors were opened.

Shortly thereafter, 38 Morane-Saulnier M.S. 406c-1s from

France’s defeated Armee de /Air arrived from Germany. It was with this

inadequate fighter that ZNDH pilots were expected to intercept growing numbers

of U.S. heavy-bombers protected by huge swarms of P-51 and P-47 escorts. Croat

airmen were additionally hampered by a wholly inadequate early warning system

and usually scrambled only as the enemy was overhead. Whenever the defenders

did get airborne, they invariably found themselves hideously out-numbered by

mostly superior aircraft.

From the close of 1943, USAAF and RAF bombers repeatedly

violated Croatian airspace with impunity, as they overflew the Balkans on their

way to targets in Austria. The ZNDH lacked sufficient strength to oppose these

Allied intruders, until interceptor units of the Hrvatska Zrakoplovna Legija

(Croatian Air Force Legion) were formed with Luftwaffe assistance on December

23. A month later, Mussolini’s Salo Republic contributed 12 new specimens of

the Macchi M.C.202 Folgore. At 372 mph, the sleek “Lightning” lived

up to its name. Croat pilots loved the Macchi for its superb handling

characteristics and 3,563-feetper-minute rate of climb, but found that the two

7.7-mm Breda-SAFAT wing guns lacked punch. Only its twin 12.7-mm machine-guns

in the engine cowling were effective by contemporary standards.

But HZL crews had little immediate opportunity to put the

Folgore through its paces, because Allied raids on Austria by way of the

Balkans fell off for the first quarter of 1944. They used the lull to gain

additional training experience until April 1, when the unit was redesignated 1./Jagdgruppe

Kroatien. The next day, an immense bomber stream of the 15th U.S. Air Force

passed over Croatia on its way to attack the Austrian industrial city of Steyr.

The ZNDH’s early raid alert system had not improved during the previous four

months, and only two interceptors could be scrambled in time to confront the

Americans returning from their mission. With hundreds of 12.7-mm M2 Browning

machine-guns firing at them, the Folgore pilots dashed unscathed among the

flight of B-24 heavy-bombers, one of which fell burning out of the sky.

In hopes of better positioning themselves to meet the foe,

several dozen Croatian fighters were relocated from the unit’s base at Lucko to

Zaluzani airfield outside Banja Luka. British intelligence learned of the move,

and Numbers 1, 2, and 4 Squadrons in the South African Air Force’s Number 7

Wing were alerted. Their Spitfire Mk.IXs, some carrying a pair of 250-pound

bombs apiece, appeared without warning over Zaluzani in a low-level attack that

overtook the defenders on April 6. Twenty one ZNDH aircraft were destroyed on

the ground, including a Folgore and all save 1 Morane-Saulnier, together with

16 Luftwaffe warplanes.

Of greater loss was the death of Cvitan Galic, who perished

when the M.S.406, under which he took shelter during the raid, exploded and

collapsed on him in full view of his horrified comrades. With 38 confirmed and

5 unconfirmed aerial victories, he was Croatia’s second-highest scoring ace.

Yet another 21 ZNDH machines were caught parked in the open and destroyed by

bomb-laden Spitfires six days later.

Despite these appalling losses, the 1./Jagdgruppe Kroatien dispatched

two pairs of Morane-Saulniers and Fiat Freccias to patrol for damaged or

separated B-24s. Instead, they were attacked by two Mustangs 6,500 feet above

Zagreb. The decidedly inferior MS.406s and G.50s were no match for

state-of-the-art P-51s, which shot down one each of the older French and

Italian fighters in short order. If anything, it is to their credit that the

other two pilots were able to successfully elude their technologically superior

pursuers.

When provided with better aircraft, the Croatians went over

eagerly to the offensive. They had always been outnumbered by their enemies, so

a numerical advantage possessed by the Anglo-Americans meant little to them.

Before the end of April, Unterofizier Leopold Hrastovcan flew his Macchi past

escorting Mustangs to blast a four-engine Liberator that crashed outside the

village of Zapresic. Several days later, Unterofizier Jakob Petrovic’s Folgore

closed in on a British de Havilland DH.98 Mosquito fighter-bomber famous for

its laminated plywood construction. “The Timber Terror;” as it was

also known, fell trailing thick smoke toward the sea.

Petrovic and another comrade were evenly matched against two

USAAF P-38s on May 1, when one of the “Fork-Tail Devils” was shot

down and the other driven off, badly damaged. While pilots of the 1./Jagdgruppe

Kroatien continued to score against Anglo-American intruders for the rest of

spring and throughout summer, war on the homefront was spreading across the

Balkans.

In mid-summer, 15 long-distance R-series Stukas were

dispatched to Croatia, where they pounded Red Army columns at the southeastern

border. They joined eight Ju.87D-5 dive-bombers delivered to the

Antiteroristicka jedinica Lucko, an antiterrorist unit based near Zagreb, at

Lucko, the previous January. In an unexpected assault on September 20,

partisans captured Banja Luka, over-running the airbase at Zaluzani airfield.

Thinking fast, many ZNDH crews jumped into their Dornier bombers, engines

started just after propellers cleared hangar doors, to machine-gun waves of

partisans, and got away at the last, possible moment. Once airborne, they

circled back around to provide suppressive fire, enabling their comrades’

escape. A few days later, the city and airbase were recaptured in a powerful counterattack

launched by Croat and German troops.

Further Croatian requests for specialized aircraft from the

Luftwaffe were answered in mid-September with the arrival of a dozen Fieseler

Fi.167A-0s. They were indeed purpose-built, but not for any antipartisan role.

The big biplane had been originally designed in 1938 to serve aboard the German

Navy’s projected aircraft carrier for reconnaissance and torpedo bombing. Graf

Zeppelin was never completed, however, and the few examples already produced

were put to use flying coastal patrols in Denmark before being transferred to

the ZNDH. Like its more famous Fieseler, the Storch, the Fi.167 was endowed

with extraordinary STOL characteristics, capable of landing almost vertically

anywhere. With a maximum take-off weight of 10,690 pounds, its short-field and

outstanding load-carrying capabilities made it an ideal transport flying ammunition,

food, medical supplies, or evacuating wounded to and from Croatian Army

garrisons besieged by Tito’s insurgent armies.

On October 10, while on a mission to a Croatian position

near Sisak, a lone Fi.167 flown by eight-kill ace, Bozidar “Bosko”

Bartulovic, was jumped by five P-51 Mk IIIs of the RAF’s 213 Squadron.

Bartulovic’s rear gunner, Mate Jurkovic, used his 7.92-mm MG 17 machine-gun to

score a lethal hit on one of the attacking Mustangs before the Fieseler, too,

was destroyed by the other four, thereby achieving perhaps the last and

certainly most remarkable aerial victory in biplane history. Both Bartulovic

and Jurkovic parachuted to safety. Some of the remaining Fi.167s were installed

with a single 2,200-pound bomb used effectively against otherwise impenetrable

rebel positions.

Beginning in December 1944, things began looking up for the

Croats. As a measure of the high regard with which he held them, Goering

equipped two ZNDH squadrons with the Luftwaffe’s best piston-driven fighter.

The Kurfurst, or “Elector Prince;’ was the last and fastest in a long

operational line of the Messerschmitt Bf. 109 series, which had begun 10 years

earlier. Optimized for high altitudes, a nine-foot-wide chord, three-bladed VDM

9-12159 propeller converted the 1850/2000 PS output of the new Messerschmitt’s

DB 605DB/DC power plant into thrust. As such, the fully loaded aircraft was

able to top 445 mph at 22,500 feet, while enjoying an extraordinary rate of

climb at 4,820 feet per minute. Armament comprised twin, 13-mm MG 131

machine-guns in the nose with 300 rounds each, plus a single, engine-mounted MK

108 cannon firing 65 30-mm rounds.

Thus equipped with the Kurfurst, ZNDH pilots evened the

playing field against their Western opponents. What the Croat interceptors still

lacked in numbers, they made up for with a fighter at least the equal of the

American Mustang or British Spitfire, and a highly effective bomber-buster, the

K-4’s real function. Both German and Croat fliers took advantage of the

airplane’s high performance to avoid enemy escorts and go after the USAAF B-17s

and B-24s.

The ZNDH also made do with much older machines. On December

31, a Dornier Do.17E paid a surprise New Year’s Eve visit to the RAF’s 148

Squadron base at Grabovnica near Cazma, where the old medium bomber dropped its

1,100-pound payload on the airfield, causing numerous casualties among partisan

defenders. Supply dumps were wrecked, and a four-engine Handley-Page Halifax

heavy-bomber was destroyed.

On March 24, 1945, ZNDH aircraft grounded at Lucko airfield,

for lack of petrol, were incinerated during a napalm attack delivered by RAF

Mustangs of Numbers 213 and 249 Squadrons. Defensive flak shot down a P-51 from

the former Squadron, but three Messerschmitts, one Morane-Saulnier, and a

Focke-Wulf 190 were ruined. Several other aircraft were damaged. The day

before, the Croats won their last aerial victories, when Mihajlo Jelak and

15-“kill” ace, Ljudevit Bencetic, flying Bf-109G-10s, claimed two

British P-51s between them. Jelak was hit by enemy fire but managed to safely

crash-land his wounded Gustav. With Communist forces overrunning Zagreb,

Bencetic addressed his crews at Lucko airfield for the last time. They had

performed their duties splendidly, he said, and flying with them was the

greatest personal honor he had ever known, but they were released now from

their loyalty oath and at liberty to return to their homes.’

As Bencetic returned the final salute of his men, a pair of

aged Rogozarski R-100 trainers flown by Lieutenants Mihajlo Jelak and Leopold

Hrastovcan were attacking a railway bridge spanning the Kupa River with

50-pound bombs. Destroying it would delay the enemy’s advance toward Karlovac,

allowing time for the city to be evacuated. As Hrastovcan’s biplane circled for

another pass, it was hit by ground fire and crashed near the foot of the

bridge, where he was dragged from the wreckage and shot to death.

Fighting against 12-to-1 odds, Croat airmen continued to

score hits on the enemy. Their final flight operation occurred on April 15,

1945, when a Dornier Do.17Z medium-bomber, covered by a pair of

Messerschmitt-109Gs, raided the partisan airfield at Sanski Most, destroying

two Communist warplanes, damaging several others on the airfield, and

machine-gunning ground personnel to escape with damage.

The last ZNDH remnants in the 1st Light Infantry Parachute

Battalion had joined up with the Croatian Army’s Motorized Brigade as early as

the previous January, from which time they were in constant action south of

Zagreb against an advancing partisan army. The few surviving paratroopers were

still fighting in Austria a week after the German surrender, refusing to lay

down their arms until May 14, 1945.

During the immediate postwar period, Tito assumed a

magnanimous pose, extending “general amnesty” to all opponents. But

his apparent generosity was a ruse luring war-weary servicemen to their doom.

Every ZNDH airman the Communists could lay their hands on was imprisoned and

tortured, often for many years. Bozidar Bartulovic, the Fieseler biplane pilot,

whose rear gunner shot down an attacking Mustang, had bailed out when a

0.50-caliber bullet partially shattered his skull and shot away his right eye.

After long-term recovery at a Zagreb hospital and later graduation from

officers’ training school, he was arrested and sent to a POW camp until his

release in 1946, then rearrested and sentenced to 15 years imprisonment. Upon

his release, Bartulovic fled to Munich, Germany.

Many of his comrades fared far worse. All high-ranking ZNDH

officers were rounded up and shot.