The lembos (Lat. Lembus, Plautus, Mercator, I, 2,81 and II, 1,35) was

an Illyrian fast ship, probably originally used in piracy and very important

for the Romans for its carrying capacity of men, equipment and booty. It could

be open and aphract, with a strong ramming capacity and rowed at two levels

(biremis). From this the liburna was developed.

Pompey, ordered to clear the seas of pirates, had full authority over

the entire Mediterranean and Black Seas, and all land within 80km (50 miles) of

the sea. He raised 500 ships, 120,000 soldiers and 5000 cavalry. He then

divided this force into 13 commands. The only area left (deliberately)

unguarded was Cilicia. Pompey took a squadron of 60 ships and drove the pirates

from Sicily, into the arms of another squadron. Then he swept down to North

Africa, and completed the triangle by linking up with another legate off the

coast of Sardinia, thus securing the three main grain-producing areas that

served Rome. Pompey then swept across the Mediterranean from Spain to the east,

defeating or driving pirates before him. The remnants duly gathered in Cilicia,

where Pompey had planned a full assault by both land and sea. A few pirate

strongholds were destroyed, and there was a final sea battle in the bay of

Coracesium, but thanks to Pompey’s clemency, most pirates surrendered easily.

POMPEY THE GREAT DEFEATS CILICIAN PIRATES, 66 BC It was Pompey the

Great who was to crush the Cilician pirates and give freedom and security to

the waterways of the Roman Republic. To do this, Pompey received from the

Senate, after long debates, extraordinary powers in 67 BC: the proconsular

power (Imperium Proconsolare) for three years throughout the Mediterranean

basin to the Black Sea with the right to operate up to 45 miles inland. Fifteen

legates were put under him with the title of propraetores and 20 legions

(120,000 men) and 4,000 riders, 270 ships and a budget of 6,000 talents. In a

rapid and well-organized campaign he defeated the pirates. Two months sufced to

patrol the Black Sea and root out troublemakers; then it was the turn of Crete

and Cilicia (App., Mithridatic War, 96). The pirates were destroyed in their

own territories and they surrendered to Pompey a great quantity of arms and

ships, some under construction, some already at sea, together with bronze,

iron, sail cloth, rope and various kinds of timber. In Cilicia 71 ships were

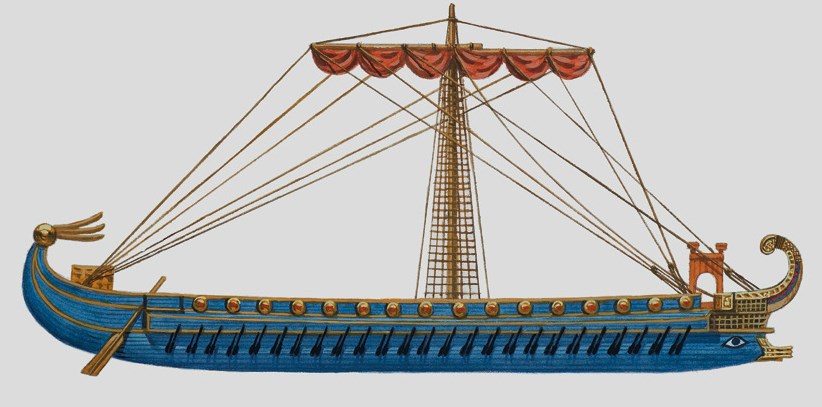

taken for capture and 300 for surrender. This scene shows an amphibious

operation of Pompey the Great’s fleet against the pirates. The main Roman ship

is a `Three’. The burning Cilician ships are two myoparones.

The early period of Roman expansion was marked by a

succession of wars with neighbours near and far. First there were the other

states in Italy and then Carthage. When Carthage was beaten, the Rome turned

its gaze to the east. Macedonia, Greece and then Pontus (modern Asiatic Turkey)

fell to Rome over a number of years. But it was while Rome was focused on these

wars that piracy raised its head in the eastern Mediterranean.

For many years, the island of Rhodes had used its navy to

suppress piracy in order to protect her position as a transit port in the

lucrative east-west trade. However, Rhodes fell foul of the Macedonian kingdom

and appealed to Rome, who sent a force of quinqueremes to defend her ally. The

combined force compelled the Macedonians to sue for peace. Under the treaty,

the Romans gained the small island of Delos, which they returned to Macedonia

on the condition that it was run as a free port with no taxes or dues on goods

entering or leaving. Unfortunately for Rhodes, the presence of this offshore

tax haven undermined the revenues from her trade and the island and her navy

went into long-term decline. With Rhodes no longer able to police the waters of

the Mediterranean, the pirates spread their depredations beyond the eastern

Mediterranean. Ports and coastal towns were sacked, shrines desecrated and

cargoes, crews and ships taken at sea. The goods, ships and their crew were

then sold off at various markets. Wealthy captives were held to ransom.

The ordinary merchants of the ancient world sailed in ships

far simpler in design than the warships of the period. Such ships could not

afford the expensive oarsmen of the warship and had to rely instead on the

single main mast and single square sail with the optional refinement of bowsprit

and second, smaller square sail. Later ships added a triangular sail above the

main for extra propulsion. The merchant ships could be as much as 60m (200ft)

in length, possibly with more than one mast, but were more usually just 30m

(100ft) long and 8m (26ft) in beam, drawing just 3m (10ft) of water and

carrying loads of around 100-150 gross tons. Built for capacity rather than

speed, they were not fast – perhaps 5-6 knots if the wind permitted. Crews were

kept to a minimum since they ate into the profits: 10-15 men were usual on a

medium-sized ship; less on a smaller ship and more on a larger one.

While the sail-powered merchantman was dependent on the wind

for speed, the oarpowered warship or pirate ship was unhampered by head winds

or rough seas. Since the square sail meant the merchantman would sail fastest

heading down wind, the pirate tactics were simple: cruise into the wind so that

any prey coming the other way would find it next to impossible to escape.

Alternatively, the pirates would lurk behind headlands for a quick spurt to

catch any passing trader. Fear and intimidation were the best weapons to induce

a quick surrender. Faced by a pirate ship apparently bristling with armed men

and with no way to escape, most merchant ships would be forced to capitulate.

The pirates could then use their oars to spin the ship around and bring their

bows up to the victim’s stern, where it was safe to board. The crew would be

bundled below and well trussed up and the pirates would install their own crew

to sail the prize for home.

So widespread and powerful did the pirates grow that when

the rebel leader Spartacus and his army of ex-slaves became trapped in the toe

of Italy in 72 BC they negotiated with the pirates to evacuate the whole army –

some 90,000 men, women and children – by ship. The pirates were then paid even

more by the Roman politician Crassus not to fulfil the contract. The problem

with piracy reached such a pass that two Roman Praetors, together with their

staff, were captured by the pirates. Another squadron attacked Rome’s port at

Ostia and sacked other towns in the region.

Pompey’s Appointment

In many ways, the Roman elite benefited from the pirate’s

activities. For those who could afford to buy, piracy kept the price of slaves

low and supply plentiful. On the other hand, it did interrupt trade. So the

wealthiest classes in Rome, who needed to buy slaves to work their estates,

benefited while the lower, merchant classes and their workers suffered. In 69

BC, however, the pirates excelled themselves and plundered the island of Delos.

It comes as no surprise, then, that the consul Metellus was voted an army to

reduce the pirate base in Crete. He headed off and set about his task, rounding

up some pirates and settling down to besiege others in the main pirate base on

the island.

In 67 BC, the Roman tribune Aulus Gabinus presented a bill

to the Peoples’ Assembly to appoint the most famous general of the age,

Pompeius Magnus – better known as Pompey – to sweep the pirates from the seas

once and for all. The ramifications were enormous. Clearing the Mediterranean

of the pirates would greatly ease the lot of the ordinary man. Indeed, prices

in the markets of Rome fell significantly simply at the presentation of this

bill. The Roman citizens, the plebs, were right behind the idea. However, the

wealthy ruling classes, the senators and, to a lesser extent, the knights were

almost universally against the bill. The one notable exception was Julius

Caesar. Ever the populist, he supported the motion. It was passed.

Pompey had already enjoyed a very distinguished military

career. He had first been appointed commander of an army at the age of 24,

supporting Sulla’s side in an earlier civil war. Although he was occasionally

accused of cruelty, he proved so successful during campaigns in Sicily and in

Africa that he was acclaimed ‘Great’ by Sulla. He even asked for and was

granted a triumphal procession that should not have been permitted given his

youth and junior rank. No sooner had Sulla died than another civil war loomed

and Pompey found himself in Spain, leading an army against Sertorius. Although

he was supported by a second army under Metellus, it was Pompey who gained a

second triumph. It was a truly remarkable achievement.

The resources initially proposed for Pompey in this next

task were huge. They comprised some 200 ships plus oarsmen, sailing crew and

marines totalling over 40,000 men. He was to be given 15 legates (military

commanders), an unlimited treasury, and unlimited powers over the whole of the

Mediterranean and up to 7km (4.5 miles) inland. However, the vote was postponed

for a day and when the final amended version was passed the Assembly voted

through an even bigger force. This consisted of no less than 500 ships, 120,000

infantry and 5000 cavalrymen, 24 senior military commanders and a pair of

quaestors (magistrates responsible for military finances). Against this,

however, the pirates were reputed to have 1000 ships at their disposal and

bases both large and small all around the Mediterranean.

Pompey versus the Sea

Pirates 67 BC

The pirates needed to avoid contact with more powerful

military elements so that they could continue to extract plunder from less well

defended ports and communities in the Mediterranean, while the Roman squadrons

sought to round up the pirates and bring them to a very rudimentary justice.

Pompey chose to divide the Mediterranean into discrete areas and conquer each

in turn, starting in the far west off the coast of Spain. This drove the

pirates steadily towards the southern shore of Turkey and the final bloody

confrontation happened near Soli, in modern-day southern Turkey. There,

Pompey’s assault routed the pirates, destroying their strongholds in the area.

Although hailed as a great victory Empire, it was not successful in the long

term. Just a few years later in Sicily, Anthony and Octavian had to combine to

combat Pompey’s son, who had turned to piracy.

Planning and preparation are key to the success of any

enterprise and Pompey’s orders were decisive. The Mediterranean was divided

into 13 areas and each one was allocated a commander and a force appropriate to

the threat in that area. Pompey retained direct control over a reserve of 60 of

his best ships – almost certainly quinqueremes with well-trained crews.

Starting with the waters west of Italy, the local commanders restricted the

seaborne movements of the pirates and forced them ashore, where they were

destroyed. It took only 40 days to sweep these seas clean of the menace. Those

pirates that escaped, made their way back to bases along the inhospitable

Cilician coast in what is now Turkey.

The greatest threat to Pompey’s success came from inside

Rome. The general’s wide powers were both envied and feared, especially by

those who benefited most from the activity of the pirates. The consul Piso,

safe within the walls of Rome, went so far as to countermand Pompey’s orders,

paying off some of the ships’ crews. While Pompey’s fleet sailed south around

the foot of Italy to tackle the pirates in the Adriatic, Pompey himself hurried

back to Rome. There, his friend and supporter Gabinius had already started the

process of dismissing Piso from his position as consul. This would have been a

dreadful and permanent stain on his family honour and reputation. Having got

his crews back, however, Pompey had the bill withdrawn, and thus Piso lwas let

off. Meanwhile, Rome had been transformed – the markets were full of foodstuffs

from all over the Mediterranean and prices were almost back to normal. From

Rome, Pompey made his way to Brundisium on the east coast of Italy and took

ship for Greece and the final part of the war.

Some of the more cut-off pirate squadrons surrendered to

Pompey, who confiscated their ships and arrested the men. He stopped short of

having the pirates crucified – the normal form of execution for such a crime

(all the survivors of Spartacus’ rebellion had been crucified). Thus

encouraged, a large number of pirates also sent a message of surrender from

Crete, where they were sitting out a siege by Metellus. Pompey accepted their

surrender and despatched one of his own commanders, Lucius Octavian, with

instructions that no one should pay heed to Metellus but only to Octavian.

Mettelus was understandably livid and continued the siege. Octavian, following

Pompey’s orders, now masterminded the defence of the city on behalf of the

pirates. Eventually the city – and Octavian – were forced to surrender.

Metellus humiliated his rival in front of the assembled army before sending him

back to Rome with a flea in his ear.

Pompey’s rehabilitation worked. Around 20,000 former pirates

were eventually settled in underpopulated inland areas like Dyme in Achea, on

the northern coast of the Peloponnese, and Soli, in what is now Turkey.

However, a substantial body of the miscreants occupied the mountain fastnesses

of Cilicia with their families. The inevitable battle with Pompey’s men took

place at Coracesium in Cilicia in 67 BC. That there was a battle and that the

pirates lost it is about all that is known. Pompey’s victory was not

surprising, however. The trained and experienced men of Pompey’s army and navy,

with their proper equipment, were more than a match for the undisciplined pirates.

It is worth recording that among the spoils of war after that last battle were

90 ships equipped with bronze-headed rams.