By the time of John Pym’s death from disease in early

December 1643 much of the architecture of Parliament’s eventual victory was in

place, and he must take a large share of the credit for that. A military

alliance with the Covenanters, in the service of yet another covenant, this

time between the two kingdoms, was underpinned by novel forms of taxation which

would provide the basis for public revenues for over a century (assessment,

excise and customs). These were reinforced by penal taxation and seizure from

those who opposed the aims of the Covenant. Parliamentary committees,

proliferating like mushrooms, allowed Parliament to act as an executive body,

albeit a rather poorly co-ordinated one.

Pym’s contribution to sustaining the political will to

implement these measures was considerable, but not necessarily popular, even

among those who had been riveted by his compelling speeches in May and November

1640. Although his influence grew out of those influential speeches, what he

had in the end championed was quite different from a defence of parliamentary

liberties and the Church of England. A week or so before Pym’s death,

Parliament took a further highly significant step. In early November,

Parliament had authorized the use of a new Great Seal, the highest symbol of

sovereignty, and on 30 November it was entrusted to six parliamentary

commissioners. It represented an escalation of the argument that the King

enjoyed his powers in trusteeship, exercised in partnership with Parliament.

When the King was absent or in danger of wrecking the kingdom, so the argument

had gone, then Parliament could assume trust in his place. Now, it was said,

those using the Great Seal were enemies of the state, which was not currently

entrusted to the King. The new seal made the implications of this plain: it did

not include the King’s image but that of the House of Commons, and the arms of

England and Ireland. As one commentator put it, there was consternation among

‘all the People’ who had ‘reason to believe that, at last, the divisions

between the King and Parliament would become irreparable, and that there would

be no hopes left of their being reconciled to one another, the breach made in

his Majesty’s authority being so great, that it portended nothing less than the

ruin of the state and the dissolution of the monarchy’. In all these ways,

defence of parliamentary liberty was clearly no longer the same as defence of

the ancient constitution.

Pym’s death also coincided with a reorganization of

parliamentary military command. The formal alliance with the Covenanters called

into being the Committee of Both Kingdoms, which took over from the Committee

of Safety in February 1644. It was the first body to have responsibilities in

both kingdoms. In one sense it filled the gap of a single executive body,

acting as a kind of parliamentary Privy Council. But it was also a highly

political body, on which opponents of the Earl of Essex were prominent, men

anxious for a clearer military victory in order to secure a peace on demanding

terms. Holles, for example, was not on the committee, but Cromwell was, and its

terms of reference compromised the powers granted to Essex in his commission.

Pym, man of the moment in 1640, died at a point when the parliamentary cause

had plainly moved a long way from the aims set out at the meeting of the Long

Parliament – it was now a military alliance with the Covenanters, more or less

on condition that the English church be reformed along the lines of the kirk,

in the hands of a parliamentary committee acting as an independent executive

and likely to seek a decisive military victory over their King. National

subscription to the Solemn League and Covenant was promoted from 5 February,

underpinning these aims.

In this context, the fate of William Laud has an obvious

significance – putting the issues of 1640 back in the forefront of people’s

minds, and paying an easy price to the Covenanters for their military support.

Laud had been impeached on 19 October 1643, the first step on what proved a

long path to his execution, and it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that

this was a narrowly calculating political act, another way of promoting

Protestant unity without raising difficulties about church government, and an

easy way to curry favour with the Covenanters. It also perhaps reflected how

Laud was the personification of the dangers of Catholic conspiracy, all too

evident following the Cessation. One newsbook argued that ‘the sparing of him

hath been a provocation to Heaven, for it is a sign that we have not been so

careful to give the Church a sacrifice as the State’. Strafford had died for

the latter, but now revenge was sought on Canterbury in the cause of God: ‘he

having corrupted our religion, banished the godly, introduced superstitions,

and embrewed both kingdoms at first in tincture of blood’. But there was a more

prosaic reason – while he lived on as Archbishop of Canterbury he had to

approve ecclesiastical appointments and, though he did his best to comply, some

appointments made demands on him that he could not in conscience approve. In

any case there can have been little to justify the prosecution of an ageing

bishop, or the ‘rancorous hatred’ with which his prison cell was searched for

incriminating evidence. The hostility perhaps bears testimony as much to the

difficulties of 1643 as to the certainties of 1640. It offered the same

comforts as the bonfire of ‘pictures and popish trinkets’ staged on the site of

Cheapside Cross in January 1644 to mark the defeat of the Brooke plot. Even so,

it was another year before the trial was concluded.

Pym had died at more or less the pivotal moment in the

fighting. By not losing in 1643, when military fortunes had favoured the

royalists, Parliament had put its armies in a position to win, particularly in

alliance with the Covenanters. This was not simply because of the intervention

of the Covenanters, since the royalist momentum had already been halted,

particularly by the victories at Newbury and Winceby. The first major

engagement of the spring was at Cheriton (29 March), on the approaches to

Winchester. A decisive victory that owed nothing to the Covenanters, it led to

a royalist withdrawal and the recapture of Winchester. This not only halted

royalist advances in the west but signalled, like Winceby, that the parliamentary

cavalry was becoming a match for the royalists. It was followed within ten days

by the fall of Salisbury, Andover and Christchurch (although Winchester Castle

held out) and, by early April, Waller was on the verges of Dorset. Clarendon

felt that the impact of the defeat at Cheriton on the royalist cause was

‘doleful’.

When the Covenanters arrived, then, it can plausibly be

argued that the momentum was already with Parliament and that some of the

further progress of parliamentary arms did not depend on their presence. On the

other hand, this was also partly an illusion caused by royalist strategy. The

King’s forces now dispersed, seeking to re-establish control in the regions, a

necessary preliminary to building strength for a renewed offensive, and that

continued to be a reasonably hopeful strategy. In any case, the Covenanters”

army was undoubtedly significant in shifting the balance further in favour of

Parliament, opening a new front in the north and introducing a new field army.

In late spring there were five parliamentary armies in England. The Covenanters

and the Fairfaxes in the north put pressure on Newcastle’s position, Manchester

was besieging Lincoln, Waller was the dominant force in the west and Essex was

preparing to take the field. Against this, Rupert’s army was in the north-west

and potentially able to offer some support to Newcastle, but Charles had

sustained a presence in the centre only by amalgamating his army with the

remnants of Hopton’s. Prince Maurice was laying siege to Lyme, with a small

force, and there was no army available to confront Manchester. The Covenanters

did not turn the tide, but they did contribute significantly to the problem of

over-stretch faced by the royalist forces.

Commitment to dispersal, and the demands of the overall

situation, undoubtedly affected the movements of Rupert’s army during the

spring. He had left Oxford for Chester in March, where he was lobbied to pursue

the relief of Lathom House, but the chief priority was the relief of Newark,

which was achieved on 21 March. It was a significant victory, not least because

the besieging forces surrendered siege artillery, 3,000-4,000 muskets and large

numbers of pikes. But there was an immediate demand for Rupert’s aid in the

south. Many of his troops came from Wales and he set off there for

replenishment and supply, but was recalled to Oxford on 3 April. The order was

countermanded the following day, but it is evidence of the stretch that was now

felt in the royalist ranks. Newcastle’s pleas for support in Yorkshire

continued to go unheard and the royalists had also been defeated at Nantwich.

On 11 April, Selby fell to the Fairfaxes and Newcastle withdrew to York. This

allowed the Covenanters and the Fairfaxes to join forces at Tadcaster a week

later, threatening the extinction of the royal cause in the north.

In this situation a parliamentary advance on Oxford, where

morale was flagging, was quite possible. On 16 April the Oxford parliament was

prorogued following an address imploring Charles to guarantee the safety of the

Protestant religion; the failure of another political initiative and the death

of what Charles was later known to have called his ‘mongrel parliament’. For

Parliament, Oxford and York were the two key military objectives, and the royalist

forces were stretched to cover both. While Charles sought to strengthen the

position around Oxford with garrisons at Reading, Wallingford, Abingdon and

Banbury, Rupert left once more for the north. The Committee of Both Kingdoms

was also interested in both objectives, and as the Earl of Manchester took

control of Lincolnshire he was sent to York rather than Oxford. Nonetheless,

parliamentary advances in May put such pressure on the royalist position in

Oxford that the King decided to leave. Charles left Oxford on 3 June with 7,500

men, leaving 3,500 to defend the town, armed with all his heavy artillery, and

marched west via Burford, Bourton and Evesham. By the time he reached Evesham

it was known that Tewkesbury had fallen to Massey and he opted to take up

quarters at Worcester, arriving on 6 June. Three days later Sudeley Castle fell

and he ordered a further withdrawal to Bewdley.

These then were promising days for the parliamentary armies.

The King had withdrawn from Oxford and York was under pressure. But the

initiative was lost. Essex was sent to relieve Lyme rather than join Waller in

a pursuit of the King. This crucial and controversial decision was taken at a

council of war at Chipping Norton, at which both Waller and Essex were present.

It was an odd one, perhaps intended as a prelude to moving into the west and

cutting off the King’s supply. Historians have subsequently blamed Essex and

Waller for a crucial error, and at the time the Committee of Both Kingdoms was

shocked by the decision and ordered Essex to return, something he notoriously

failed to do, on 14 June. Having decided to take this course, and to ignore a

direct order from the Committee of Both Kingdoms, it was of course important

for Essex to succeed, and at first he did. He lifted the siege of Lyme on 14

June and took Weymouth the next day. He now resolved to push on into the west.

It is more than possible that this reflects in part personal frictions between

Waller and Essex, who had been at odds before and seem to have squabbled during

this campaign. But this disagreement was probably exaggerated retrospectively

by Waller and his supporters – he initially supported the decision. Essex

challenged Parliament to relieve him of his command and got his way – on 25

June he was ordered to move west in accordance with his wishes. This order

allowed him to continue the march he had already commenced in defiance of his

previous orders.

Meanwhile, Waller pursued the royal army, which was moving

back via Woodstock and Buckingham. He found it difficult to engage the army,

and its very mobility was a problem, since it might suggest a move either on

York or on London. Waller therefore had to have the defence of London in mind.

This rested on a small and hastily assembled force under Major-General Browne

and it appeared vulnerable until Waller made it back to Brentford on 28 June.

In the end the indecisive engagement at Cropredy Bridge on 29 June was the only

fruit of these manoeuvrings, and this must surely count as a lost opportunity

for Parliament. After the battle the royal army was able to march off in

pursuit of Essex in better spirits than the parliamentarians.

In the north, however, the parliamentary campaign was

decisive. York had been under siege by Leven and Fairfax since 22 April and the

only hope of relief lay with Rupert. In May and June he won a string of

victories in Lancashire. These mobile campaigns were frustrating parliamentary

armies in the south, but the position in York looked bleak. On 13 June the Earl

of Newcastle had been invited to negotiate its surrender and it was thought

that the city could only hold out for another six days.

On 14 June, Charles wrote a fateful letter to Rupert. ‘If

York be lost I shall esteem my crown little less, unless supported by your

sudden march to me, and a miraculous conquest in the South, before the effects

of the Northern power can be found here; but if York be relieved, and you beat

the rebels” armies of both kingdoms which were before it, then, but other ways

not, I may possibly make a shift upon the defensive to spin out time until you

come to assist me’. The loss of York would be a catastrophe except in the very

unlikely event that Rupert was able to get away and secure victories in the

south before the parliamentarian armies got there. On the other hand, if York

was relieved and the northern army defeated, Charles might avoid defeat long

enough for Rupert to come to his aid. Relief of York and defeat of the northern

army were the best hope for the royalist cause.

This was a realistic view, but it conflated the relief of

York and the defeat of the rebels: as it was to turn out it was possible to

relieve York without defeating the Scottish and parliamentarian forces. Charles

had not known this of course. His command to Rupert was:

all new enterprises

laid aside, you immediately march according to your first intention, with all

your force, to the relief of York; but if that be either lost or have freed

themselves from the besiegers, or that for want of powder you cannot undertake

that work, that you immediately march with your whole strength directly to

Worcester, to assist me and my army, without which, or your having relieved

York by beating the Scots, all the successes you can afterwards have most

infallibly will be useless to me.

Again, the possibility was not recognized here that York

might be relieved without defeating the besieging army.

On 28 June it was clear that Rupert was coming. Besiegers were too exposed between the walls of a defended city and an army able to line up in one place, rather than as an encircling force, and on 1 July the siege had been broken up. The parliamentary forces withdrew to Tadcaster and York had been saved. But Rupert seems, not unreasonably, to have interpreted the letter to mean not simply that he should relieve York but that he should engage and destroy the besieging army. He therefore decided to seek battle despite the clearly expressed view of the Earl of Newcastle that it should be avoided. Most subsequent commentators have taken Newcastle’s side: with the relief of York the King’s position had been rendered more stable and there was no good reason for risking an engagement with the besieging army. In fact Rupert had received numerous letters in the weeks before Marston Moor containing more or less the same message, and urging haste, and so he was not unjustified in seeing his orders in this way. It seems that other royalist commanders feared that Rupert, left to his own devices, would have given priority to establishing full control of Lancashire. But he was also aggressive by instinct and that he interpreted his order in that way would not have surprised Colepeper: when he heard that the letter had been sent he said to Charles, ‘Before God, you are undone, for upon this peremptory order he will fight, whatever comes on’t’.

For those interested in contingencies then, the moment at

which Charles drafted that clause, or the moment when Rupert read it, was

crucial to the course of the war in England. With York relieved, the King in

what turned out to be a successful pursuit of Essex, and Oxford secure, honours

might have been said to be even. But Rupert chose to engage numerically

superior forces, with catastrophic results for the royalist cause.

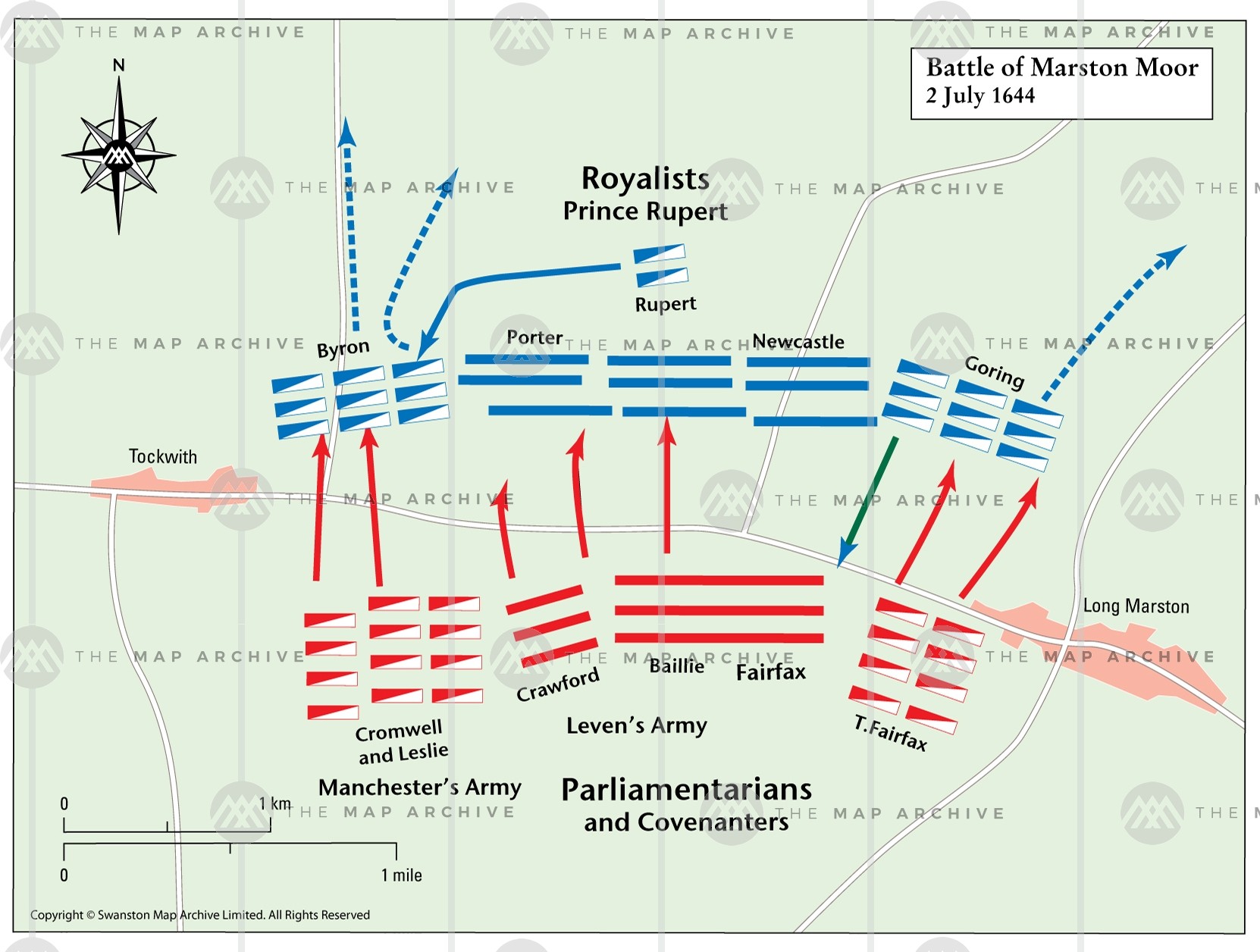

Battle was joined at Marston Moor on 2 July. Rupert’s forces

were considerably outnumbered, particularly the cavalry. His relieving army and

the force garrisoning York numbered about 18,000. The parliamentarians, by

contrast, probably had around 28,000 men, the result of the confluence of

forces under the command of Leven, Sir Thomas Fairfax and Manchester. The bulk

of the parliamentary forces, about 16,000, were Scottish and Leven was in

overall command both as the ranking officer and as a man of formidable

experience in the European wars. His forces were drawn up with the infantry in

the centre, cavalry on the right under Fairfax and on the left under Cromwell

and Leslie. Opposite Cromwell were Rupert’s cavalry, commanded by Byron, and

Fairfax was opposed by Goring. Infantry numbers were fairly equal – around 11,000

on either side – but the parliamentary advantage in horse was considerable.

This was not a guarantee of success, however, because the ground on which the

battle was fought did not favour horse riders – furze, gorse, ditches and

rabbit holes broke up the ground, making rapid advances difficult. Byron, in

particular, was protected by rough ground.

The initial deployment was not complete until late

afternoon, and several hours of inconclusive skirmishing had achieved little by

7 p.m. At that point Rupert thought the battle would be postponed until the

next day, and Newcastle was repairing to his coach to enjoy a pipe of tobacco.

But as a thunderstorm broke, the parliamentary infantry began to advance. The

rain interfered with the matchlocks of the royalist advance guard and the

parliamentarians” infantry successfully engaged with the main body of the

royalist infantry. But the royalist riposte was very successful. Goring

advanced on the parliamentary cavalry ranged against him, and his men began to

inflict heavy losses. Byron, perhaps encouraged by the sight, advanced on

Cromwell, but in doing so had to tackle the difficult ground himself. Perhaps

that contributed to the ensuing rout, in which Cromwell’s cavalry were

triumphant. But with Fairfax’s cavalry now defeated and Goring’s men inflicting

heavy losses on the infantry it seemed as if Rupert’s decision might be

vindicated. Many Scottish troops fled and at one stage all three

parliamentarian generals appeared to be in flight, thinking that a royalist

victory was in the offing.

It was the discipline of Cromwell’s cavalry that transformed

this position. Fairfax made his way behind royalist lines to tell Cromwell what

had happened on the opposite flank. Cromwell was able not only to rally his

cavalry but to lead them back behind the royalist lines before leading a

devastating charge on Goring’s forces from the rear. This was utterly decisive

– the royalist infantry were now completely exposed, and outnumbered. Most

surrendered, and the parliamentary victory was total. It is likely that the

royalists lost at least 4,000 men, probably many more, and a further 1,500 were

captured. Rupert left York the next morning with only 6,000 men and Newcastle

refused to make a fist of the defence of York, preferring exile, he said, to

‘the laughter of the court’. York surrendered two weeks later and the

parliamentary forces in the field now easily outnumbered the royalists. This

was the worst case that Charles’s letter had sought to avoid: the loss of both

York and his field army.

Marston Moor was certainly a massive blow to royalist

morale, and decisive for the war in the north, but Parliament was robbed of an

outright victory in England by a combination of poor military judgement and

political hesitancy. The military adventure launched by the Earl of Essex and

the reluctance of the Earl of Manchester to pursue a complete victory allowed

the King to recover his position in the west and enter winter quarters in

Oxford in triumph.

In mid-June, having lifted the siege of Lyme and captured

Weymouth, Essex set off into the west. Waller could not offer support partly

because of the reluctance of the London Trained Bands to serve for long away

from home. Nonetheless, supported by the navy under Warwick’s command, Essex

initially enjoyed considerable success. By early to mid-July he was threatening

Exeter, where Henrietta Maria was recovering from the birth of her daughter,

Henrietta Anne, on 16 June. Essex refused her safe conduct to Bath and offered

instead personally to escort her to London. Given what subsequently happened,

this would have been a considerable boon to the parliamentary cause, but

Henrietta Maria refused – as both she and Essex knew she faced impeachment in

London. Instead she fled to France, on 14 July, and never saw her husband

again.

Influenced by the threat of the northern army moving south,

and also perhaps by this threat to his wife’s safety, Charles moved decisively

after Essex. On 26 July he reached Exeter and rendezvoused with Prince Maurice,

who was at the head of 4,600 men, at Crediton the following day. Essex,

meanwhile, was further west at Tavistock, where he had been received

triumphantly – Plymouth had been secured. Cut off by a royal army and having

secured Plymouth this might have been the moment for discretion, but instead

Essex resolved to push on. On 26 July he decided to go on into Cornwall,

arriving at Lostwithiel on 3 August. The King had pursued him, arriving at

Liskeard the previous day.

Now bottled up, with the King’s army behind him, Essex had put

himself in a desperate position. On 30 August he prepared to withdraw. The

following night his cavalry were able to ride away, itself something of a

puzzle since the King had been forewarned and yet apparently failed to cover

the likely route of escape. The infantry fought a retreat to Fowey but were cut

off by the arrival of a force under Goring, which commanded the road. That

night Essex instructed Skippon to make such terms as he could while Essex

himself slipped away on 1 September. The King offered surprisingly generous

terms to Skippon, given the dire position in which Skippon found himself.

This was a massive blow to morale. Mercurius Aulicus was

withering in its scorn, asking ‘why the rebels voted to live and die with the

earl of Essex, since the earl of Essex hath declared he will not live and die

with them’. According to the terms of surrender negotiated by Skippon the army

was to be allowed to march out with its colours, trumpets and drums, but

without any weapons, horses or baggage apart from the officers” personal

effects. They were offered convoy, the sick and the wounded were to be given

protection, and permission was given to fetch provisions and money for the

defeated troops from Plymouth. These could be claimed as honourable terms, but

they did not stick, and the defeated army was subject to humiliations amounting

to atrocity. The royalist convoy could not protect the unarmed soldiers from

attack and local people, men and women, joined in the assault. They were

stripped by the women, and left lying in the fields. Some were forced ‘to march

stark naked, and bare footed’, and pillage and assault continued. One victim

was a woman three days out of child bed, stripped to her smock, pulled by her

hair and thrown into the river. She died shortly after. Ten days later the

survivors, perhaps 1,000 of the 6,000 who surrendered, marched into Poole,

‘insulted, stripped, beaten and starved’. Their numbers had been winnowed by

desertion, but there were many who died on the road, after an honourable surrender.

If the propaganda effect was dire, the strategic importance could not be

exaggerated: ‘By that miscarriage we are brought a whole summer’s travel back’.

Essex’s adventure, for which he was solely responsible, had gone a long way

towards grabbing stalemate from the jaws of victory.

Worse was to come, at least in political terms. Fairfax,

Leven and Manchester apparently felt that Marston Moor would force Charles to

seek terms, and they did little to pursue an outright victory. In Manchester’s

case, at least, this reflected his belief that a lasting peace would be one

recognized as honourable by all parties, and could not be delivered by total

military victory. War was a means to peace, and had to be treated with caution.

This hesitancy allowed Charles to consolidate his position during September.

Following his triumph over Essex, Charles moved eastwards again, arriving in

Tavistock on 5 September. Having abandoned the attempt to retake Plymouth he

sought to relieve garrisons further east and his forces established themselves

at Chard, and both Barnstaple and Ilfracombe were retaken. His aim was to

strengthen the garrisons at Basing House and Banbury to shore up the position

of Oxford. This began to look like a potential threat to London and it finally

spurred Manchester to bring his Eastern Association forces into the King’s way.

It proved difficult to co-ordinate and supply the parliamentary armies, and the

Trained Bands contingents were reluctant to move too far, so Waller was forced

to pull back from the west in early October, unable to gain support for his

position in Sherborne. As Charles continued to advance Parliament began to

consolidate forces, calling off the siege of Donnington on 18 October. The

King’s next objective was to lift the siege of Basing House, but Essex and

Manchester joined forces there just in time, on 21 October, and the King was

forced to withdraw to Newbury. Together with Waller’s remaining forces, and

levies from the London Trained Bands, the parliamentarians were finally able to

bring a large force, perhaps of 18,000 men, to bear on a royal force which on

some estimates was only half as strong.