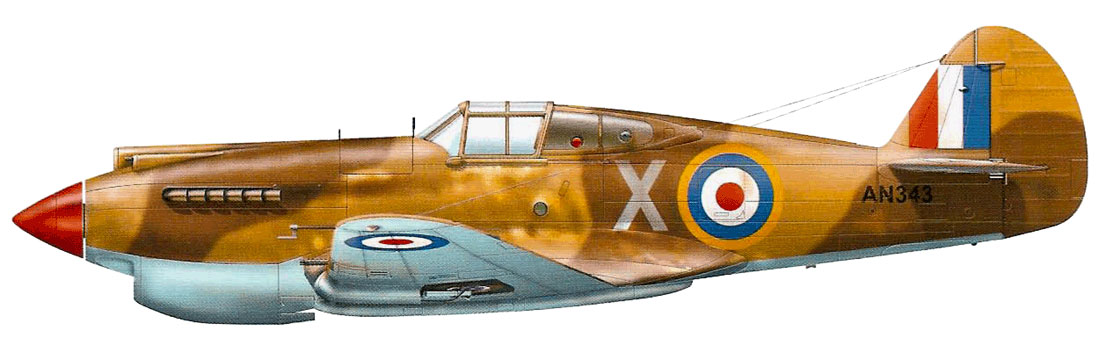

Tomahawk Mk.IIb Unit:

3 Sqn, RAAF Serial: X (AN343) Pilot – F/O Bruce Evans.

North Africa. He was shot down and KIA on November 15th, 1941.

Kittyhawk Mk.I Unit: 3 Sqn, RAAF Serial: CV-J North Africa, 1943.

P-40L (Kittyhawk Mk.II) Unit: 3 Sqn, RAAF Serial: CV-V Pilot – CO of 3

Sqn, RAAF (in future Air Vice Marshall) Brian A. Eaton

BY DAVID WILSON

On 20 September 1939, the Australian Government approved the

plan to raise a six-squadron air expeditionary force for service overseas.

Although this plan was later negated by the decision in November that RAAF

resources should be employed to ensure the success of the Empire Air Training

Scheme, a RAAF flying unit was deployed to the Middle East to assist the 6th

Division of the Second Australian Imperial Force as an element of General

Wavell’s army that was protecting the Suez Canal and Egypt. This unit was 3

Squadron, which had been flying Hawker Demon two-seat biplane fighters from

Richmond. Under the command of Squadron Leader I.D. McLachlan, the squadron

personnel departed from Sydney aboard the Orontes on 5 July 1940. The personnel

arrived at Port Tewfik on 20 August. They commenced training with Westland

Lysander army cooperation aircraft at Ismailia, before moving to Helwan, south

of Cairo, on 16 September. At Helwan 3 squadron was finally equipped with two

flights of Gloster Gladiator biplane fighters, four Gloster Gauntlet biplane

fighters, and a flight of army cooperation Lysander aircraft from RAF sources.

The Gladiator pilots trained in air fighting tactics, the Gauntlets were used

as improvised dive- bombers and the Lysander crews practised for their tactical

reconnaissance role, before the Gladiators and the Gauntlets were flown to

Gerawla, east of Mersa Matruh, early in November.

The squadron fought the Italian Air Force (Regia

Aeronautica) for the first time on 19 November 1940. Flight Lieutenant B.R.

Pelly, escorted by Squadron Leader P.R. Heath, and Flying Officers A.C. Alan

Rawlinson and H.H. Alan Boyd, was reconnoitring east of Rabia, when the

formation was intercepted by eighteen Fiat CR-42 fighters. The Australian

Gladiators, for the loss of the popular Heath, claimed to have shot down or

damaged six Italian fighters. From this time until the commencement, on 9

December, of Wavell’s offensive to force the Italians from Sidi Barrani, the

squadron maintained three fighters on stand-by to counter any enemy aerial

incursions. The fighters were not required, but the unit did undertake practice

dive-bombing exercises with the Western Desert Force.

In a brilliant campaign, General Richard O’Connor forced the

more numerous Italian forces from the fortress of Bardia and captured Tobruk.

After cutting off the retreating Italian Army at Beda Fomm on 7 February, the

Western Desert force was poised to attack Tripoli. However, the situation that

developed in Greece during January 1941 resulted in the weakening of the desert

force to bolster the Greek Army against German invasion. The Regia Aeronautica

proved ineffectual in combating the superiority of the three RAF fighter

squadrons, one of which was the Gladiator-equipped 3 Squadron, which, for the loss

of five Gladiators and two pilots (Flight Lieutenant C.B. Gaden and Flying

Officer J.C. Campbell), was credited with the destruction of twelve enemy

aircraft. During February the Australian squadron was equipped with Hawker

Hurricane monoplane fighters and, from its base at Benina, was assigned the

task of defending Benghazi from attacks by Luftwaffe aircraft based in Sicily

and Tripolitania. Due to the lack of early warning facilities and the Luftwaffe

tactics of attacking just before dawn or after dusk, 3 Squadron could claim

only one success—on 15 February, Flying Officer J.H.W. Saunders succeeded in

destroying a Junkers JU-88.

Luftwaffe operations indicated that General Erwin Rommel,

who had arrived in Tripoli during the later days of February with the Afrika

Korps to assist the Italians, would not be prepared to accept a passive role.

On 24 March, he initiated an offensive which resulted in the capture of

Benghazi on 3 April, and the subsequent retreat of the British forces to the

vicinity of Bardia by the 11th, leaving the 9th Australian Division surrounded

in Tobruk. The RAF fighter squadrons had limited success in covering the

retreat and protecting the British forces from the Luftwaffe. During the

ten-day, 800-kilometre retreat, 3 Squadron operated from nine separate bases.

After evacuating from Benini on 3 April, it undertook a fighting withdrawal.

Although it was impossible to supply adequate cover for the retreating troops,

the squadron did claim some victories against the Luftwaffe. Eight Hurricanes

destroyed five Junkers JU-87s during the afternoon of 5 April while they were

covering the withdrawal of the 2nd Armoured Division near Charruba. An hour

later Flight Lieutenant J.R. ‘Jock’ Perrin led a formation of nine Hurricanes

that surprised twelve JU-87s and claimed the destruction of nine of the enemy.

On 14 April, the squadron was operating from Sidi Barrani when Flying Officer

W.S. ‘Wulf’ Arthur and Lieutenant A.A. Tennant (South African Air Force)

combined to shoot down two twin-engined BF-110s near Tobruk. The following day

Squadron Leader Peter Jeffrey shot down a Junkers JU-52 transport and

successfully strafed three more that had just landed near the Bardia–Capuzzo

road. The Australian squadron was withdrawn to Aboukir, for rest, on 20 April.

The reverses in the Western Desert, the fall of Greece and

the invasion of Crete marked the nadir of British fortunes in the Middle East

and Mediterranean. There was no respite for the hard-pressed Wavell and his

forces. As 3 Squadron was being withdrawn for rest, the situation in Vichy

French-controlled Syria compelled military action to prevent the potential that

German aircraft could refuel at Syrian bases and threaten the oilfields of

Persia and Iraq. Wavell, who was preparing for Operation Battleaxe, an

offensive to be mounted in June with the aim of relieving Tobruk, was ordered,

in combination with Free French Forces, to invade Syria to prevent any such

incursions. The force assigned for the Syrian campaign comprised the 7th

Australian Division, the 5th Indian Brigade, some composite mechanised units

and the Free French Division. A light-bomber squadron, one army cooperation and

one fleet air arm squadron, as well as two and a half fighter squadrons

supplied air support. Having converted to the American Curtis P-40 Tomahawk

fighter at Lyddia in Palestine, 3 squadron was to play a prominent role in the

campaign. Their first operation was a strike by five Tomahawks that left six

French Morane fighters destroyed on the ground at the Rayak airfield on 8 June.

That afternoon four Tomahawks escorted Bristol Blenheims that attacked oil

tanks at Beirut. The squadron flew various roles over the next two weeks:

interceptions, naval patrols, tactical reconnaissance, close air support of the

ground troops and bomber escort duties, all of which gave the opportunity to

engage the enemy in combat. On 14 June, Peter Jeffery led eight Tomahawks into

combat against a like number of JU-88s (with Italian markings) during which

three of the German bombers were shot down.

The Anglo-French advance proceeded quickly until 12 June,

when the Australians were halted by Vichy French counterattacks near

Merdjayoun. The Free French had advanced to within sixteen kilometres of

Damascus, and the British fighter units supported both forces by offensive

patrolling. On the 15th, 3 Squadron reconnaissance flight sighted twelve Vichy

tanks and 30 motor vehicles near Sheikh Meskine, and Jeffrey and Flying Officer

Peter Turnbull each destroyed a Vichy Glenn Martin bomber. Attacks on enemy

targets in the Kuneitra area failed to prevent the Vichy French ground forces

from threatening the British line of communications. The Vichy Air Force was

active, and the demand for protective patrols by the limited British fighter

force could not be met.

The hardening of Vichy French resistance led to a

reorganisation and reinforcement of the attacking forces. Lieutenant General

Lavarack assumed command of I Australian Corps, which had been augmented by a

brigade from the 6th British Division and an independent force (Habforce) moved

from Iraq to threaten Palmyra. Air reinforcements consisted of the combined 260

Hurricane squadron (comprising RAF pilots and RAAF ground crew) and a Blenheim

bomber squadron, thus enabling 3 Squadron to be allocated to support the

Australian Corps. The Australian Tomahawks attacked tactical targets and the

aggressive strafing of enemy airfields destroyed many enemy aircraft on the

ground. Tomahawks also escorted the Blenheims on raids to assist Habforce. On

the 28th, nine 3 Squadron Tomahawks escorted Blenheims on a raid before

intercepting and shooting down all six enemy Glen Martin bombers that were

attacking Habforce units. Flight Lieutenant Alan Rawlinson was credited with

three victories; Peter Turnbull was credited with the destruction of two

bombers and Sergeant R.K. Wilson claimed the remaining bomber. However, action

was not always in the Australians’ favour. On 10 July, they were escorting

Blenheims on a raid near Hammara when five Dewoitine fighters, attacking from

below the formation, shot down three of the Blenheims before the Tomahawks

could intervene. But retribution was swift. Peter Turnbull shot down two

Dewoitines and Flying Officer John Jackson, Pilot Officer E.H. Lane and

Sergeant G.E. Hiller claimed one each.

When Syrian operations were suspended on 12 July, 3 Squadron

moved to protect Beirut from possible German air reaction from bases in the

Dodecanese Islands and Crete, before returning to the Western Desert, where it

resumed operations from Sidi Haneish on 3 September. Many of the original

pilots, like Rawlinson, Perrin and Turnbull, returned to Australia toward the

end of 1941. In May, Squadron Leader Gordon Steege had been posted from 3

Squadron to assume the command of 450 Squadron, which finally became

operational with Australian ground and aircrews in January 1942. The dilution

of experience within 3 Squadron continued with the appointment, on 13 June

1941, of Flight Lieutenant B.R. Pelly to command the newly arrived 451

Squadron. When Pelly returned to Australia he passed the command to Squadron

Leader V.A. Pope, RAF on 25 June 1941. Despite its lack of experience, the unit

built its proficiency during a series of artillery shoots, photographic and

tactical reconnaissance sorties.

Operation Battleaxe proved a failure and the lull in ground

operations resulted in 451 Squadron flying only 372 sorties in the period 1

July–14 October. On 9 August, Pope inaugurated photographic sorties to

photograph the German positions surrounding Tobruk, and plans were made for a

detachment of two Hurricanes from the squadron to operate from within the

perimeter. These aircraft operated for some months, where, despite almost daily

aerial reconnaissance missions and air raids, the Axis forces were never aware

of the underground shelters in which they were housed. Despite increasing

Luftwaffe activity in September—the squadron lost six aircraft—the unit was

able to report the presence of enemy tanks near Acroma on 11 September and to

closely monitor the movements of this column as it advanced to Rabia and then

its withdrawal to its start line.

Operation Crusader, the offensive planned by General

Auchinleck, the new Commander-in-Chief of the Allied Forces in the Middle East,

to destroy the German Army’s armoured forces, relieve Tobruk and clear

Tripolitania, commenced on 18 November. Both the Australia fighter squadrons

were involved in the preparatory and subsequent operations. The RAF fighter

squadrons were reorganised into three groups: one party would move to a forward

airfield to prepare for the arrival of the aircraft; a second party would

maintain the aircraft and then follow and relieve the first party that would

then be available to move further forward. These two groups preceded the third

group— the headquarters, workshops, stores and transport—thus ensuring the

mobility of the squadron. Given the fluidity of the subsequent actions in North

Africa, this proved a sensible arrangement. Although the BF-109F flown by the

Luftwaffe was superior to the desert-modified British Tomahawk and Hurricane

fighters, the Luftwaffe did not seriously impair the tactical reconnaissance

operations of 451 Squadron or engage 3 Squadron fighter sweeps. On 22 November,

two aerial battles were fought that established the superiority of the British

fighter units. During the morning 3 Squadron escorted a formation of Blenheim

bombers when they were intercepted by fifteen BF-109s. In the ensuing melee,

three Tomahawks and two BF-109s were shot down. That afternoon 3 Squadron

joined with 112 Squadron, RAF, in a battle with twenty BF-109s. Although the

Germans had the height and speed advantage, the two formations assumed

defensive circling manoeuvres, with individual pilots seeking to exploit any

momentary vulnerability of their opponents. Being further from their home bases

that the British, the German fighters, due to lack of fuel, were forced to

break the stalemate by disengaging and flying west.

Although the ebb and flow of the ground battle between the

Eighth Army and the Afrika Korps fluctuated between the combatants, the Axis

aerial situation, despite the balance of aircraft losses being in favour of the

Luftwaffe, did not, in general terms, threaten RAF freedom of action during the

campaign. The 451 Squadron Hurricanes, allotted to undertake tactical

reconnaissance for XIII Corps, did so with little interference from enemy

aircraft. The squadron did, however, lose personnel as a result of the fluid

ground battle. On 27 November, Flight Lieutenant Carmichael, Sergeant ‘Nil’

Fisher, Corporal Keith Taylor and Aircraftman Don Bailey, Arthur Baines,

‘Tubby’ Ward and five other airmen were captured by an enemy column that

attacked the landing site at Sidi Azeies.

The fighters however, were able to give substantial cover to

the ground forces. For example, on the afternoon of 25 November Peter Jeffery

led 3 and 112 Squadrons over Sidi Rezegh, where they encountered an enemy

formation of 70 BF-110s and JU-87s that were attacking New Zealand troops. The

RAF Squadron engaged the top cover of German and Italian fighters, while 3

Squadron attacked the BF-110s and JU-87s. Much to the delight of the ground

troops, the Tomahawk pilots dispatched seven of the enemy, probably destroyed

one and damaged another eight, for the loss of one Tomahawk. The British force

destroyed a total of ten enemy aircraft.

Early in December, 3 Squadron re-equipped with the Curtis

P-40E Kittyhawk. This aircraft was a development of the basic P-40, but was

more heavily armed than its predecessors. In the meantime 450 Squadron had

deployed to Gambut Main, where it joined the Desert Air Force on 16 February

1942. Six days later Sergeant R. Shaw claimed its first aerial victory: a JU-88

shot down in flames.

Rommel, with his usual resilience, mounted a counterattack

in January 1942. The Eighth Army withdrew to Gazala, where Auchinleck planned

to hold the Germans prior to initiating a British offensive. The defence was

based on a series of strong points such as Bir Hacheim and Knightsbridge,

which, together with the armoured killing ground that became known as ‘The

Cauldron’, was synonymous with the heavy fighting. The two Australian fighter

squadrons, 3 and 450, were active from the opening of the battle on 27 May.

During that day 3 Squadron Kittyhawks dropped 22 250-pound bombs, damaging

several tanks. Consequent actions were a mix of ground attack sorties in

support of the British Army or protecting the same from the incursions of the

Luftwaffe: the Free French defensive position at Bir Hacheim was the target for

350 enemy sorties per day. The statistics for operations flown on 16 June

indicate the intensity of the Australian squadrons’ effort. From only thirteen

aircraft available, 3 Squadron flew 62 operational sorties while 450 Squadron

flew 25 bomber escort missions and then another fifteen fighter-bomber missions

later in the day.

After the bloody battles of June, the Eighth Army was forced

to withdraw under the wings of the Desert Air Force to a defensive position

with its right flank resting on the Mediterranean Sea and its left protected by

the impassable Qattara Depression. On 1 July Rommel opened the first Battle of

El Alamein, advancing toward El Alamein and the approaches to El Ruweisat. The

Desert Air Force opposed this advance with vigour. The two Australian squadrons

flew with Boston light bombers to attack Deir el Shein, fighting a running

battle with BF-109s during the outward journey that resulted in the loss of a

Kittyhawk. With the priority given to close support of the troops on the ground

and the interdiction of German transport, aerial victories were few. One was

claimed on 4 July—a relatively typical operational day during the battle. The

two Australian units reconnoitred the coastal road to Daba and strafed a supply

column near Ras Gibeisa. That afternoon they bombed landing grounds west of

Daba before 450 Squadron machine-gunned a long column of enemy transport on the

road. Flight Sergeant D.H. McBurnie shot down a BF-110 reconnaissance aircraft.

To finalise the operations for the day, 3 Squadron bombed trucks at Sidi Abd el

Rahman and 450 Squadron spied on enemy movements as far west as Fuka.

Although 3 and 450 Squadrons were active in covering the

British retreat, 451 was withdrawn to Haifa in Palestine during February 1942.

During March the squadron deployed to Cyprus to protect the island from

high-flying German reconnaissance aircraft. The squadron removed the armour and

half the guns to lighten the Hurricanes to improve their performance. One

pilot, Flight Lieutenant R.T. Hudson, claimed to have flown his Hurricane to an

altitude of 12 000 metres (2000 metres above the fighter’s normal service

ceiling), but only one success was claimed. Flying Officers Lin Terry and Jack

Cox combined to shoot down an Italian Cant 107-C reconnaissance aircraft. On 8

January 1943, the unit moved to Mersa Matruh, from where they were involved in

mundane patrols over the Nile Delta. Even the attachment of three Supermarine

Spitfires did not improve morale. In the first six months of 1943, the unit had

a single action. On 22 February, a JU-88 had the better of a brief fight. On 23

July 1943, 451 Squadron lost three of six Hurricanes that had joined a strike

force of Martin Baltimore light bombers, Beaufighters and Spitfires on an

ineffective strike on targets on Crete.

The squadron was re-equipped with Spitfires and commenced a

new phase of operations from Poretta, Corsica on 23 April 1944, when it

escorted a formation of 24 North American B-25 Mitchell bombers to attack a

railway bridge at Orvieto, Italy. During the return flight the formation was

intercepted, and Flying Officer Wallis claimed a share in the destruction of a

FW-190 fighter. Even though the majority of the bomber escort and armed

reconnaissance flights from Poretta were unopposed, the Luftwaffe was still

capable of making its presence felt. On the night of 11 May, a JU-88 dropped

anti-personnel bombs on Poretta, killing two pilots and six of the squadron

ground staff. In the air the Luftwaffe was less deadly. On 25 May, Flight

Lieutenants House, Thomas and Bray each claimed the destruction of a FW-190

after a sharp encounter over Roccalbegna, north of Rome, accounting for three

of the seven enemy aircraft shot down by 451 Squadron during the month. Another

highlight was the covering of the landing by French commandos on the island of

Elba.

Squadron Leader W.W.B. Gale assumed the command of 451

Squadron early in July, but was shot down a week later while engaged in a

reconnaissance flight over the bridges spanning the Arno River between Florence

and Empoli. Squadron Leader G.W. Small assumed command on 7 July. Next day the

squadron moved to St Catherine, from where it flew fighter sweeps over

Marseilles and Toulon prior to flying cover for the Allied landing on the coast

of southern France on 15 August. The unit moved to St Cuer, from where, as has

been already noted, it deployed to Hawkinge.

While 451 Squadron was stalled in Palestine, the two other

Australian fighter squadrons were withdrawn for rest before participating in

the second Battle of El Alamein. During this period Flying Officer A.W. ‘Nicky’

Barr enhanced his reputation. On 11 January 1942, he claimed victories over a single

Italian Fiat G-50, and two BF-109s. During the combat Barr was wounded in the

legs, and his Kittyhawk was badly damaged, forcing Barr to crash land behind

enemy lines. Assisted by the local tribesmen, Barr was able to gain information

on enemy dispositions that proved valuable after his return to the unit. Barr

was promoted to the rank of squadron leader and assumed temporary command of 3

Squadron. On 30 May, Nicky made a spectacular high-speed crash landing, but was

able to return to the Allied lines on foot, having passed though a tank battle

en route. However, on 25 June Barr, badly wounded, bailed out of his severely

battle-damaged Kittyhawk. He was captured, but managed to escape from

captivity. In an eight-month period evading recapture in Austria and Italy, he

eluded the enemy again and again, finally becoming involved with an Allied

Airborne Special Services unit, for which he was awarded the Military Cross. He

had previously been awarded a DFC and bar, and remains, with a score of twelve

enemy aircraft to his credit, the highest scoring 3 Squadron pilot of the

Second World War.

At the end of September the Kittyhawks reverted to the

fighter-bomber role, when they attacked Axis positions near Sidi Abd el Rahman

and Ghazal. Sorties during October were a mixture of interceptions,

fighter-bomber and bomber-escort missions. These missions enabled the

respective commanders of 3 and 450 Squadrons, Squadron Leaders R.H. ‘Bobby’

Gibbes and J.E.A. Williams, to blood new pilots, thus ensuring that the units were

at peak efficiency for duties during the forthcoming battle at El Alamein.

General Montgomery began the battle on 23 October 1942, but

it was not until 4 November that the Axis forces were in full retreat. The

British fighter units escorted light bomber formations, undertook tactical

reconnaissance flights and strikes against Luftwaffe bases. Throughout the

battle, the Luftwaffe resisted stoutly, despite the long-range efforts of the

Kittyhawks to disturb their airfields. Although profitable, these operations

were not without cost; 450 Squadron lost its commander when he was forced down

near Buq Buq on 31 October. Williams was captured and, like Catanach, was

imprisoned in Stalag Luft III, one of the Gestapo victims to be executed as a

result of his efforts in the ‘Great Escape’.

Once the Eighth Army broke through the Axis lines, the

Desert Air Force was utilised to hinder the enemy retreat. Between 6 and 19

November, the fighter units were based at seven separate airfields. One task

was escorting light bomber formations. On 9 November, Sergeant Dave Borthwick,

of 450 Squadron, was part of the high cover for a formation of Bostons when he

was shot down. Although wounded, he managed to parachute to the relative safety

of the desert. On landing, he used his parachute material to bind his wounds.

Despite his bindings, he could not walk, and crawled on hands and one leg for

four days, eating beetles and licking the early morning dew from desert plants

to sustain him. He finally found an Arab tomb, and was discovered by a King’s

Royal Rifle Regiment patrol. He had lost 25 kilos in weight during his ordeal.

Borthwick was awarded an MID for his fortitude.

So keen was the fighter force that on 9 November the advance

parties of the 3 and 450 Squadron’s ‘B’ echelons appear to have been leading

the whole Allied Forces pursuit. For example, a 3 Squadron party was located to

the west of Sidi Barrani when they were strafed by BF-109s while watching the

forward element of the Eighth Army’s armoured spearhead advancing behind them.

Similarly, a 450 Squadron ‘B’ echelon was advised by the surprised armoured

column commander who found them that it may be wiser for them to wait on the

fall of Sidi Barrani before proceeding to the airfield. The advance from

Amiriya, near Alexandria, was so rapid that 3 Squadron had advanced 800

kilometres in ten days and operated from five separate airfields. On 18

December the Australians had reached the airfield at Marble Arch in Libya. The

effort was marred by the loss of five 3 Squadron ground crew members, the

victim of an enemy landmine that had been laid near the landing field.

Despite the Allied landing in Morocco during November 1942,

ensuring that the Axis forces in North Africa could not recover the initiative

in the theatre, hard fighting ensued before the final African victory. The

Australians had a reputation of making every effort to rescue downed pilots

during the campaign—successful rescues had been previously completed by, among

others, Peter Jeffery and Flying Officer Lou Spence—and the effort of Bobby

Gibbes to rescue Sergeant Rex Bayley on 21 December 1942 is an excellent

example of the hazards involved. Six 3 Squadron aircraft successfully strafed

the German airfield at Hun, leaving six enemy fighters destroyed in their wake.

Defending anti-aircraft fire shot down two of the attackers. One of the victims

was Rex Bayley, who, after successfully crash landing his Kittyhawk, radioed

that he was unhurt. Gibbes, despite Bayley’s protestations, landed his

aircraft. After releasing the half-full drop tank from the Kittyhawk’s

fuselage, Gibbes unstrapped himself from the cockpit and moved the ejected tank

from under the aircraft. When Bayley arrived, Gibbes removed his own parachute

and sat on his lap. The take-off was hazardous. There was only 300 metres

available before the ground dropped off into a wadi. Under full power, the

Kittyhawk became airborne, but not before the port wheel of the undercarriage

was demolished when it hit the earth on the opposite side of the wadi. On landing

at Marble Arch, Gibbes skilfully balanced the aircraft on its remaining

starboard wheel on landing. The aircraft ground looped, but suffered only minor

damage. Incidentally, Gibbes was himself shot down on 14 January 1943, but

evaded capture for five days before returning to Allied lines.

The Allies accepted the final surrender of Axis forces in

Tunisia on 13 May 1943. During the March 1943 breakthrough of Rommel’s

defensive line at Mareth, the squadrons flew similar roles to those at El

Alamein, and contributed to the inability of the Luftwaffe to resupply and

protect the Axis troops in Tunisia. For 3 Squadron to have been— with the

exception of Operation Battleaxe—involved in every major operation during the

North African campaign was a proud achievement. With over 200 victories, it was

the highest scoring Desert Air Force squadron. 450 Squadron had, with less

opportunity, also made its mark. In sixteen months of operations this squadron

destroyed 47 enemy aircraft in air-to-air combat, and, to give some credence to

the varied role of fighter-bombers with the Desert Air Force, destroyed 584

enemy motor vehicles.

Australian fighter pilots also served with the RAF. The most

outstanding was Clive Robertson Caldwell, who, with 28 confirmed victories, was

the highest scoring Australian ‘ace’ of the Second World War. By the time he

arrived back in Australia during September 1942, he had scored at least twenty

victories and commanded 112 Squadron, RAF. He was acknowledged as a superb

shot, and his ‘shadow shooting’ technique—a pilot would fire live rounds at the

ground shadow of an accompanying aircraft, thus honing his skills in deflection

shooting as well as allowing for the time taken for the projectiles and targets

to meet at the same spot (leading the target). He was awarded a DSO, DFC and

bar and the Polish Cross of Valour while in the Middle East. A contemporary was

John Lloyd Waddy, who served in 250 Squadron, RAF, and 4 Squadron, South

African Air Force (SAAF), before returning to Australia in February 1943.

During his service in the Middle East he was awarded a DFC and scored twelve

aerial victories.